Chapter 1

Bob’s Diary, December 1931

Michael John Burlingham

The first school I remember was a private day school in Swiss Cottage, London, to which I walked every morning from my home in St John’s Wood. This was followed by three years of public middle school in Princeton, New Jersey; two miserable years in boarding school in New York State; and two much happier years in Pennsylvania. Little did I know that my paternal grandmother and her father had also been sent to boarding schools, and hated them. When it came to my own children, I enrolled them in the Little Red School House, a private day school founded in 1921 by Elisabeth Irwin that has become a bastion of progressive education.

How, then, do I make sense of something as radical as what my father, his siblings and a handful of other kids experienced in Vienna from 1927 to 1932? Other than home-schooled children, who bypasses the school system entirely? Who gets a school founded and built around their needs? What kind of parent has the time, energy, finances and vision to do such things? Whatever the answers, whatever one may think of such a solution, surely one would agree that the Hietzing School was unusual for any time or place. In fact, in its particulars, it was unique, and the diary that my father kept while he was a student there provides a unique account of that experiment, and the larger, wider forces it embodied (Figure 1.1).

In school these last days we have been reading Pepy’s Diary and discussing its faults and contributions to the Engl. literature. And as it pleased me, the way he writes and tells I got the idea of writing a diary myself from now on. So to-day I went to a paper shop and bought this little booklet.

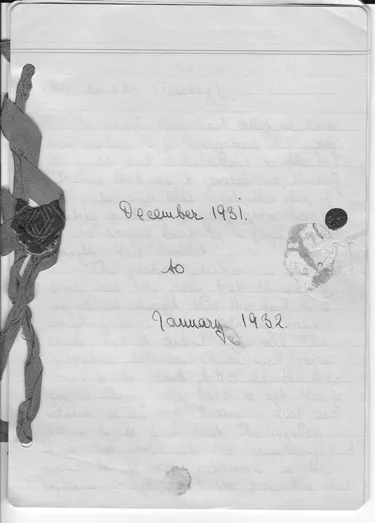

Thus, Robert Burlingham, Jr, known as Bob, starts his diary on December 1, 1931, a cold winter’s Tuesday, writing by hand in black ink, since faded to dark gray. He wrote not from 17th-century London but from 20th-century Vienna, and his diary lasted not “from now on” but rather twenty-two days, ended by Christmas festivities, an early, characteristic false start, perhaps (Burlingham, 1989, p. 248). He would title it “December 1931 to January 1932.” No great events are recorded, no plague, no war, no great fire, but as my essay shows, there are good reasons to dive into this narrative of a sixteen-year-old American boy. I have transcribed Bob’s diary exactly as it appears in the original, without corrections of any kind, whether for style, spelling or inconsistencies. Occasionally, I have put annotations within brackets for reasons of meaning or identification, but I have purposefully avoided the use of “sic.” Like his siblings, by 1931, Bob was bilingual in English and German and sometimes used a German word in an otherwise English-language document.

Figure 1.1 Bob’s Diary. Original manuscript.

On December 1, 1931, when he began to write, Bob was living at Berggasse 19 in an apartment two floors above the one occupied by Sigmund Freud and his family. Bob had a spacious bedroom to himself and once leaned out the window to record the view down the street with his new Leica rangefinder camera. I recently visited that same room and tried to recreate the view as it looks today with my digital Canon, so I know just how far out of the window he had to lean. Bob’s photo reveals Berggasse with an orderly line of parked cars in a distant center aisle and an outdoor cafe with two tables of customers. Today, the view is much the same, though somewhat obscured by trees, and the dome of the telephone-exchange building in the far distance is gone (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 1.2 View from Berggasse 19, 1931. Bob Burlingham.

Figure 1.3 View from Berggasse 19, 2016. Michael J. Burlingham.

It did not take Bob long to walk down two flights of stairs to his appointments with Anna Freud, his psychoanalyst for the past six years. Bob and his younger sister Mabbie were among Anna Freud’s first ten child analysands, and their case studies figured prominently in her first book, Introduction to the Technique of Child Analysis (1927). Child analysis was then still in its infancy, and those early experiments in adapting classical analysis to the needs of children had virtually no precedent.

Bob and his siblings were also participants in another, related experiment in child development. It acquired various names, but in day-to-day life, it was simply “die Schule” (Bob used German terms to identify and label the negatives of photos he took from 1930 to 1932), where his teachers had thought fit to include Samuel Pepys’ Diary in the English curriculum. Later, die Schule became known as the Burlingham-Rosenfeld School because Bob’s mother, Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, had put up the money to build a small schoolhouse in the backyard of Eva Rosenfeld’s home at 11 Wattmanngasse. Eva was a close friend of Anna Freud’s and in analysis with Professor, as Freud was known among his intimates. Eva had already been running her home along lines she described as a sort of Zellerhaus, an orphanage in Berlin for girls where she had been a teacher. A number of youngsters were boarding with Eva and her family, including Kyra, the daughter of dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, who had gone mad. Some of those children were in analysis; some joined the ranks of the schoolchildren. The Rosenfeld household was a lively place, bursting with youthful energy and, above all, music, which Eva (n.d., in Burlingham, 1989, p. 182) borrowed from Shakespeare in calling “our food of love” (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Portrait of Kyra Nijinsky by Serge Gres, 1935.

When Dorothy arrived to pick up Mabbie after her first sleepover at Eva’s, the child ran onto the balcony shouting, “Hello, hello, I don’t want to go home. I want to stay here!” (Burlingham, 1927). Today, the Rosenfelds’ two-story row house remains, complete with decorative wrought-iron balcony. The schoolhouse is gone, however, demolished by a bomb in World War II.

It has also been called the Hietzing School after its location in that district of Vienna, where homes had been built for the workers who attended to the Kaiser in the nearby Schönbrunn Palace. And finally, due to its diminutive size, it was known as The Matchbox School. But it might as well have been called the Anna Freud School, as it was founded in part to nurture students who were in analysis, to be supportive of psychoanalytic values, and to foster learning through the kind of progressive education that John Dewey advocated. It had but twenty-six students and a short life span – just five years – but carried an outsize influence due to the backing of Anna Freud, a former schoolteacher herself, and the presence of Erik Erikson as one of the two principal teachers, along with Peter Blos. The close connection between education and child analysis, for Anna Freud, is seen in Bob’s entry of December 1, when he calls his analytic hours “lessons” in his diary.

So what goes through the head of an adolescent in such circumstances, and what does he commit to paper? In his first entry, Bob mentions some of the current events shaping the wider landscape – the shocking bankruptcy earlier that year of the Austria’s once-mighty Credit-Anstalt bank – and fears that the Austrian schilling would be devalued. He also indirectly referenced the abysmal economic condition of many Viennese in a theme repeated throughout the diary – the Austro-German effort that commenced that year to help unemployed and poor families in need of relief during the coldest months of the year, called the Winterhilfe.

But soon Bob turned to the kind of details presented by life as it’s lived. His December 1 entry reads:

Sigurd and Walter had a fight in school and Walters nose was all swollen when he came for his lesson with Mother. I am sure it was sigurd who aggravated him till he got mad, as Sigurd was allready so against our ideas about the “Winter Hilfe.” After we left alone to consult, he ran down stairs and after fetching a Sandwich he sat down in his sloppy way and ate, & inbetween munching he made some remarks about our ideas. We thought we might feed poor children every noon in a room Felix [possibly Augenfeld, the architect] was to get for us. It certainly would be great if it were possible, but it doesn’t look so.

“Mother” was Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, an American woman in analysis with Professor. Intellectually intrigued, she had recently augmented her psychoanalytic portfolio with a training course in child analysis. Sigurd Baer and his brother Basti were Bob’s fellow students, as was Walter Aichhorn, the son of analyst August Aichhorn, a Viennese expert on adolescence. From the diary, it would seem that Walter was either one of Dorothy’s early analysands or someone she was privately tutoring. Again, it’s hard to separate the educational from the psychoanalytic; Walter was, in fact, one of her first analysands.

In 1921, shortly before the birth of her fourth child, Dorothy had left her husband, Robert Burlingham Sr, a New York surgeon who was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder. As the granddaughter of Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder of the eponymous jewelry and silver company, and as the youngest child of Louis Comfort Tiffany, the famous glass artist, she had the means to flee her husband, his destabilizing mood swings and her marriage (Figure 1.5).

Equal measures of desperation and open mindedness had led her to Vienna in 1925, ostensibly to seek psychoanalytic treatment for ten-year-old Bob. But it wasn’t long before her other children followed Bob into analysis and she herself started analytic treatment, first with Theodor Reik, then with Sigmund Freud, an analysis that lasted twelve years.

When Dorothy arrived in Vienna on May 14, 1925, she put up at the five-star Bristol Hotel on the Ringstrasse, thinking she would return to the States in a few months’ time. But Anna and Dorothy – the mother of children in analysis and their analyst – rapidly found common ground that evolved into a lifetime attachment. By 1929, Dorothy and her four children had moved into the fourth-floor apartment at Berggasse 19.

Figure 1.5 Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham 1925, by Franz Löwy.

In late 1930, the two women bought a farmhouse on twenty acres which they called Hochrotherd, after that part of Breitenfurt, some forty-five minutes by car from Vienna. From their perch overlooking a valley, as I recently saw for myself, the city was visible on the horizon, nestled between blue-misted mountains.

The “simple,” or “natural” life of the Bauern, or peasant, as Dorothy and Anna Freud (1930) imagined it, formed an important thread in their lives. At Hochrotherd, they wore peasant clothes and filled the farmhouse with striking examples of hand-painted folk furniture, now housed in the Freud Museum London. Peter Heller, an astute observer of the school he attended, later wrote that the Burlinghams cultivated “a stylization in the direction of the expensively unpretentious” (Heller, n.d., p. 6) (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham at Hochrotherd ca. 1931.

Anna Freud described the lure of country living in a letter she sent Dorothy in mid-August 1933, when Dorothy was taking Bob to Cherbourg for another trip back to the US. Since they first met, Dorothy and Anna had been separated only briefly.

I like it about farm life that it brings everything down to a simple formula, even psychic things. For instance how could one express in town the difference between being one person alone or two together? One would have to talk about the libido etc. and narcissism. Here it is much simpler: to-day f.i. it took me twice as long to weed the young peas than it would have taken if you were here again. So you see!

(Anna Freud, 1933)

Bob returned to his diary on December 2.

Walter wasn’t in school to-day. He seems to have hurt himself rather badly. In our 1st period in school Joan [Erikson] read our compositions aloud, and because mine was so bad (or I rather thought so), I had to look at the ceiling the whole time feeling as hot as a l...