- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Cape Verde Islands, an Atlantic archipelago off the coast of Senegal, were first settled during the Portuguese Age of Discovery in the fifteenth century. A "Crioula" population quickly evolved from a small group of Portuguese settlers and large numbers of slaves from the West African coast. In this important, integrated new study, Dr. Richard Lobban sketches Cape Verde's complex history over five centuries, from its role in the slave trade through its years under Portuguese colonial administration and its protracted armed struggle on the Guinea coast for national independence, there and in Cape Verde. Lobban offers a rich ethnography of the islands, exploring the diverse heritage of Cape Verdeans who have descended from Africans, Europeans, and Luso-Africans. Looking at economics and politics, Lobban reflects on Cape Verde's efforts to achieve economic growth and development, analyzing the move from colonialism to state socialism, and on to a privatized market economy built around tourism, fishing, small-scale mining, and agricultural production. He then chronicles Cape Verde's peaceful transition from one-party rule to elections and political pluralism. He concludes with an overview of the prospects for this tiny oceanic nation on a pathway to development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cape Verde by Richard A Lobban in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica africana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Politica africana1

Introduction

THE CAPE VERDE ISLANDS are not well known to the world at large. There are only nine significant islands in this West African and Atlantic archipelago, and their combined population is only one-third of a million. Yet these islands are remarkably complex in their history and composition. Indeed, such a simple matter as conceptualizing their location is more difficult than one might expect.1

Although the islands may have been visited before the Portuguese arrived, Cape Verdean history essentially starts with the settlers from Portugal and their slaves in the 1460s. From that point forward, for more than five centuries, the islands' history was characterized by Portuguese colonialism and a synthesis of the Crioulo culture. Throughout this period, the Portuguese regarded Cape Verde as an integral part of metropolitan Portugal; its position was much like that of the state of Hawaii in relation to the mainland United States. The islands have also been at the center of major oceanic crossroads. Today, they are home to Portuguese, Nigerians, Guineans, Senegalese, and other West Africans. The diverse Cape Verdean population also includes descendants of Spaniards, English, Italians, Brazilians, Sephardic Jews, Lebanese, Dutch, Germans, Americans, and even Japanese and Chinese. Much of the islands' genetic ancestry can be traced to African groups who spoke the Fula, Mandinka, and various Senegambian languages. The "purely" Portuguese have always been in the minority, but it is largely from them that the dominant language, culture, and politics have been derived. To characterize Cape Verde as a society descended from slaves is correct to a degree, but it is also a society descended from slavers, free citizens, and refugees.

Like most modern populations, the fundamental essence of the Cape Verdean people reflects enduring patterns of connection to all continents across the oceans. In this respect, Cape Verde is like a miniature version of any multiethnic modern state. To focus on Cape Verde, one must use a wide-angle lens to see the critical linkages to Europe, West Africa, and the New World and find all the points

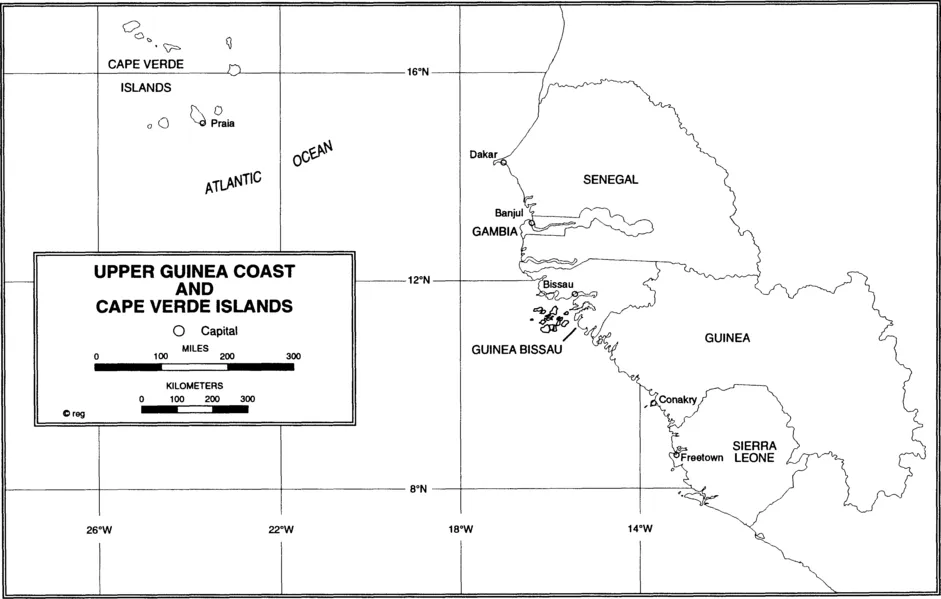

of origin, articulation, and destination of the Cape Verdean people. A view of Europe, especially Portugal, is required to detect the roots of the political and economic power that dominated Cape Verde for the vast part of its history.2 The ties to West Africa must be explored as well, not only because so many thousands of Cape Verdean ancestors came from the Upper Guinea coast but also because Cape Verde was the official, formal, and effective command post on the Guinea coast for the Portuguese until the late nineteenth century. Moreover, most grants to Portuguese or Brazilian trading monopolies in Cape Verde simulaneously included the "Rivers of Guinea."3

For simplicity, I use the term Guinea-Bissau ("Rivers of Guinea") to refer to today s Republic of Guinea-Bissau, which was known as Portuguese Guinea in colonial times. By using this term, I also distinguish this nation from neighboring Guinea-Conakry. However, for the longest part of the history of Cape Verde, the colonial administration included both the islands and steadily diminishing portions of the Upper Guinea coast. The last remaining part of Portuguese territory in this region was in Guinea-Bissau.

In the following chapters, I will describe the many ways in which the histories, peoples, and policies of these two lands are linked. Even the war of national independence, waged from 1963 to 1974 in Guinea-Bissau, had as its central goal the joint liberation and administration of the two lands. The strategy of the nationalist movement and political party—the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC)—was to struggle for independence in the forests of Guinea and pressure the Portuguese in Lisbon to release their historical hold on the Cape Verde Islands. The connections between these regions are also revealed in the fact that some of the leading Portuguese military officers who were defeated in Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique were the same men who toppled colonial fascism in Lisbon and negotiated the independence of Cape Verde some months later. The majority of the top revolutionary leaders in Guinea were of Cape Verdean origin, including Amilcar Cabral, Luís Cabral, Aristides Pereira, and Pedro Pires, all of whom fought in the forests of Guinea-Bissau. Pereira was the first president of Cape Verde, and Pires was the first prime minister of the ruling party—the Partido Africano da Independencia de Cabo Verde (PAICV)—from 1975 to 1991.

To understand Cape Verde (or Armenia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Palestine, or Scotland), one must also study its diaspora communities: The connections to the economy and power relations of the wider world are essential. In all these cases, the majority of the people claiming a common nationality do not live in the very nation that is the focus of their sentimental and even political allegiance. In the case of Cape Verde, linkages to the port towns of Europe, to São Tomé, to the coast of West Africa, to Brazil and the Antilles, and especially to New England are vital to the nation's history.

Geographic Location

Despite the term Verde ("green") in its name, Cape Verde (or Cabo Verde, in Portuguese) was named not for its verdant plant growth or agriculture but for its juxtaposition to Cap Vert (a French name) on the African coast—a point that had been reached by the Portuguese almost twenty years before the islands themselves were discovered. Although some think that the islands were named for their greenness, the fifteenth-century diaries of Christopher Columbus specifically noted the dry and barren Cape Verdean landscape; he considered the land's name a misnomer.

The Cape Verdean archipelago lies within a grid from 283 to 448 miles (452.8 to 716.8 km) off the coast of Senegal, or from 14°48' to 17°12' north latitude and 22°41' to 25°22' west longitude. Such data seem straightforward and clear today. But early Portuguese navigators believed the islands were "just downstream" in the Canary current, and even in twentieth-century Portuguese books, the islands are conceptualized as being located 1,900 miles (3,040 km) south-southwest of Lisbon. In the eighteenth century, when the interests of Brazilian slavers essentially ruled Cape Verde, the archipelago's location could be reasonably defined as 1,500 miles (2,400 km) north-northeast of Brazil. The point here is that the location of Cape Verde was conceptualized primarily by outsiders, according to the interests they had in the islands, and even some modern Cape Verdeans are as likely to focus on its location relative to Europe or New England rather than to the nearby African coast. Many of the complex issues of Cape Verdean ethnicity and identity relate to this sense of location. Clearly, the question of location involves more than longitude and latitude; it is also a matter of attitude and self-consciousness.

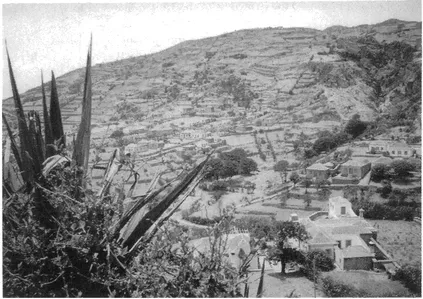

Village of Cova de Joana, Brava Island (Photo by Waltraud Berger Coli)

Climate

One might imagine that an African republic of oceanic islands would be lush and moist, but the Cape Verdean archipelago is better understood as a western extension of the Sahara Desert. In fact, the islands are extremely dry and have long been troubled by cycles of prolonged drought. The two-season weather cycle of this region is caused by the north-south movement of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The ITCZ is associated with hot, dry winters north of the zone and hot, wet summer weather to the south of the zone. The clashing weather fronts of the ITCZ in the region of Cape Verde also spawn hurricanes that regularly torment the Caribbean and the east coast of the United States in the late summer months.4

The ITCZ usually reaches only the southernmost Cape Verde Islands. In some years, it falls short of them, and there is simply no rain in the archipelago; in other years, this ITCZ front moves farther north, and the drought cycle is broken. Historically, drought cycles in Cape Verde have caused great hardships—including famine and many deaths—and led to endless waves of emigration. Seldom is the rainfall adequate for extensive, self-sufficient agriculture, particularly because much of the terrain is rocky and steep. With adequate rainfall, water conservation, and careful irrigation, there is some potential for agriculture, and in recent decades, widespread improvements have been made in this respect. Still, Cape Verdeans must import much of their food supply, thereby consuming precious foreign cash reserves.

There is also a microclimatic variation on islands with higher elevations (the highest is 9,281 feet, or 2,821.4 m). At such elevations, the moisture of passing clouds can condense at lower temperatures by the process of orographic, or pluvogenic, cooling, which can cause rain at higher elevations. In turn, this gives rise to some small but permanent springs and streams. But the flatter islands are notorious for their very low levels of annual rainfall. Yearly variation in temperature is not great: It is seldom cooler than 68°F (22°C) or hotter than 80°F (27°C).

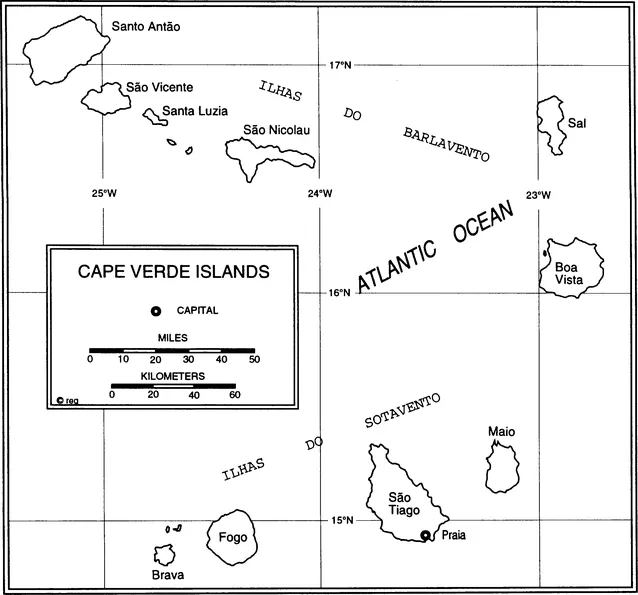

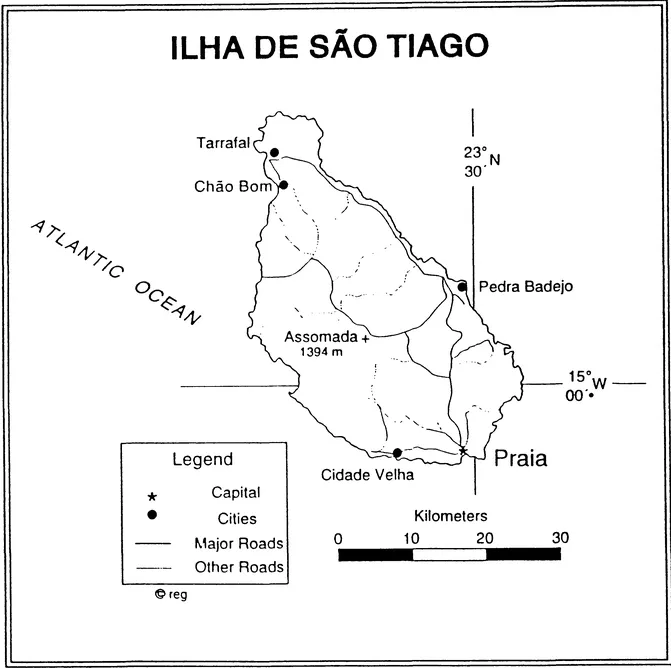

Altogether, there are twenty-one islands and islets in Cape Verde, but only nine are regularly inhabited. These include Santo Antao, Sao Vicente (with its port of Mindelo), São Nicolau, Sal (with its international airport), Boa Vista, Maio, São Tiago (with the capital, Praia), Fogo, and Brava. The islands together only cover 1,557 square miles (4,033 square kilometers)—just a little more territory than Rhode Island. The terrain is overwhelmingly rocky and volcanic, and there is very little topsoil, given the drought conditions and severe wind and water erosion. At best, only 1.65 percent of the land is arable, and much of this has been abused by absentee landowners and worn down by overgrazing (especially by sheep and goats).

The general appearance of the islands resembles a lunar landscape, with towering rocky peaks on some islands and gravelly, sandy soils. The land is deeply eroded, and there are extensive areas of very sparse settlement. Some of these volcanic islands, such as Sal, are almost flat; others are mountainous. Fogo, for example, rises to a majestic cone and has experienced numerous eruptions in historical times.

Linkages to the Wider World

The Cape Verde Islands have been both isolated from yet remarkably connected to the major events of world history. Their remote location, hundreds of miles from the nearest continent, has naturally made them vulnerable to neglect, oversight,

and abuse. But the islands were also integrally linked to wider events, such as the golden age of Portuguese discovery, the voyages of Columbus and Vasco da Gama, the pirate attacks by Francis Drake, and the provision of coal and fuel for the British empire. Cape Verde was critical in the slave trade, and it was visited by such famed U.S. ships as Old Ironsides. The islands also hosted the American Africa Squadron, used by the U.S. Navy for anti-slave trade patrols, and they figured in Charles Darwin's theory of biological evolution. In the liberation war fought against Portuguese colonial rule in Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde played a much more significant role than one might expect. Clearly, this was due to the strategic location of the archipelago: Sailors, slavers, colonialists, scientists, flyers, and o thers enjoyed the security of the islands and also found their location convenient for long-range travel to the farthest corners of the globe.

Following the struggles led by Amilcar Cabral, one of Africa's great twentieth-century revolutionary thinkers and a Cape Verdean, this island republic gained its independence in 1975. The theories and practices of Cabral are widely considered to equal those of Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Fidel Castro, and Ho Chi Minh.5 Most recently, Cape Verde has witnessed the birth of plural democracy, which resulted in a peaceful transition from the former ruling party—the PAICV—to the opposition party that now governs—the Movimento para Democracia (MpD). Cape Verde is regarded as a model democracy in West Africa, a region where one-party states, military rule, and civil war are not uncommon. During the 1992 elections in Angola, Cape Verdeans were specially selected by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to play a supervisory role, and in the same year, Cape Verdean diplomats served on the United Nations Security Council.

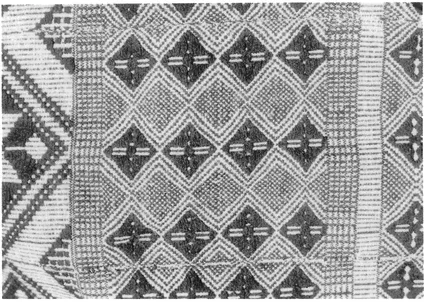

Cape Verdean pano, used in dress, dance, and the slave trade (Photo by Waltraud Berger Coli)

The most enduring resource and export of Cape Verde has been its people. Cape Verdeans have long been a people on the move—traders on the Guinea coast, colonial administrators for Portugal, revolutionaries in the national liberation of Africa, sailors and whalers on U.S. schooners and barks, laborers in the cranberry bogs of Cape Cod or the cocoa plantations of São Tomé and Principé, and merchant mariners around the world. Remittances sent home by Cape Verdeans living and working in the nation's long-lasting diaspora have been vital in sustaining the islands' population.6

The natural resources in the archipelago also include the products of the sea— diverse species of fish, turtles, and whales. And providing supplies and repairs for passing ships has been an important part of the economy for centuries. Prominent among traditional Cape Verdean crafts are the handwoven panos, cotton cloths that served as a basic unit of currency in slave and coastal trade. Cape Verdean livestock, especially horses, had a similar function, and other domestic animals were used for ship supply and hide production. The islands' other natural resources—salt, cotton, puzzolane, coffee, bananas, indigo, and urzella...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 THE HISTORICAL SETTING

- 3 SOCIETY AND CULTURE

- 4 RADICALS, SOLDIERS, AND DEMOCRATS: POLITICS IN CAPE VERDE

- 5 PEASANTS, SOCIALISTS, AND CAPITALISTS: ECONOMICS IN CAPE VERDE

- 6 CONCLUSION: CAPE VERDE AT THE END OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

- List of Acronyms

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Book and Author

- Index