- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Theory

About this book

Why do people want what they want? Why does one person see the world as a place to control, while another feels controlled by the world? A useful theory of culture, the authors contend, should start with these questions, and the answers, given different historical conditions, should apply equally well to people of all times, places, and walks of life.Taking their cue from the pioneering work of anthropologist Mary Douglas, the authors of Cultural Theory have created a typology of five ways of life?egalitarianism, fatalism, individualism, hierarchy, and autonomy?to serve as an analytic tool in examining people, culture, and politics. They then show how cultural theorists can develop large numbers of falsifiable propositions.Drawing on parables, poetry, case studies, fiction, and the Great Books, the authors illustrate how cultural biases and social relationships interact in particular ways to yield life patterns that are viable, sustainable, and ultimately, changeable under certain conditions. Figures throughout the book show the dynamic quality of these ways of life and specifically illustrate the role of surprise in effecting small- and large-scale change.The authors compare Cultural Theory with the thought of master social theorists from Montesquieu to Stinchcombe and then reanalyze the classic works in the political culture tradition from Almond and Verba to Pye. Demonstrating that there is more to social life than hierarchy and individualism, the authors offer evidence from earlier studies showing that the addition of egalitarianism and fatalism facilitates cross-national comparisons.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultural Theory by Michael Thompson,Richard J Ellis,Aaron Wildavsky,Mary Wildavsky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Theory

Introduction to Part One: Against Dualism

Social science is steeped in dualisms: culture and structure, change and stability, dynamics and statics, methodological individualism and collectivism, voluntarism and determinism, nature and nurture, macro and micro, materialism and idealism, facts and values, objectivity and subjectivity, rationality and irrationality, and so forth. Although sometimes useful as analytic distinctions, these dualisms often have the unfortunate result of obscuring extensive interdependencies between phenomena. Too often social scientists create needless controversies by seizing upon one side of a dualism and proclaiming it the more important. Cultural theory shows that there is no need to choose between, for instance, collectivism and individualism, values and social relations, or change and stability. Indeed, we argue, there is a need not to.

A recurring debate among social scientists is whether institutional structures cause culture (defined as values and beliefs, i.e., mental products) or culture causes structure.1 As our definition of ways of life makes clear, we see no reason to choose between social institutions and cultural biases. Values and social relations are mutually interdependent and reinforcing: Institutions generate distinctive sets of preferences, and adherence to certain values legitimizes corresponding institutional arrangements. Asking which comes first or which should be given causal priority is a nonstarter.

In recent decades, the social sciences have witnessed a dissociation between studies of values, symbols, and ideologies and studies of social relations, modes of organizing, and institutions.2 Cultural studies proceed as if mental products were manufactured in an institutional vacuum, while studies of social relations ignore how people justify to themselves and to others the way in which they live. One of the most important contributions of our sociocultural theory, we believe, is bringing these two aspects of human life together.

Nor do we feel it necessary to take sides in the dispute between adherents of methodological individualism, who hold that “all social phenomena are in principle explicable in ways that only involve individuals,” and partisans of methodological collectivism, who argue that “there are supra-individual entities that are prior to individuals in the explanatory order.”3 Institutional arrangements do, as methodological collectivists contend, constrain individual behavior, but it is also true, as methodological individualists insist, that institutional arrangements are held together and modified by individual action. Individuals do find themselves in an institutional setting not of their making, as Marx says, but it is individuals who create, sustain, and transform that setting. Put another way, the individual (unlike the behaviorist’s rats) shapes the maze while running it.4

We refuse also to cordon off stability from change. Cultural theory unites mechanisms of maintenance and transformation. If, as Marshall Sahlins says, change is failed reproduction,5 then a theory of change must also be a theory of stability. Moreover, this dualism obscures the enormous amount of change that is required to secure stability. Individuals continually confront novel situations requiring a great deal of effort to maintain their familiar pattern of social relations. British Tories, for instance, in the face of considerable socioeconomic and political change, maintained their dominant position within society as well as their preferred pattern of deferential social relations by changing their policies regarding welfare state measures and suffrage reform.6

The fact-value distinction, although analytically defensible, obscures the extensive interpenetration of facts and values in the real world. Precious few are the claims that do not contain both value and factual components. Ways of life weave together beliefs about what is (e.g., human nature is good) with what ought to be (e.g., coercive institutions should be abolished) into a mutually supportive whole. Cultural biases are protected by filtering facts through a perceptual screen.7 Contra Weber, however, normative beliefs about how life ought to be lived are not necessarily immune to facts.8 When the promises that adherents of a way of life make to each other (or to supporters of other ways of life they wish to recruit) are not borne out by repeated experience, the discrepancy between the expectation and the result can dislodge individuals from their existing view of how the world ought to be and thrust them into another.

Rather than counterpoising rationality and irrationality, we refer to competing social definitions of what will count as rational. No act can be classified as in and of itself rational or irrational. What is rational depends on the social or institutional setting within which the act is embedded. Acts that are rational from the perspective of one way of life may be the height of irrationality from the perspective of a competing way of life. For instance, individualists, who believe they can increase both their wants and their resources, will deem fatalistic resignation utterly irrational. But for fatalists, who tell themselves that both needs and resources are beyond their control, resignation is eminently rational.

Often superimposed upon the dichotomy between rational and irrational is the division between primitive and modern. Although this distinction highlights the vast differences among societies that exist in technological development, we find it of no use in classifying ways of life. Contra Durkheim, we insist that the march of technological progress does not release modern man from the social control of cognition. Regardless of time or space, we argue, individuals always face (and, as long as human life exists, always will) five ways of relating to other human beings. This provides the foundation for the essential “unity in diversity” of human experience.

Notes

1. See, for instance, Brian Barry, Sociologists, Economists and Democracy (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1970); and Carole Pateman, “Political Culture, Political Structure and Political Change,” British Journal of Political Science 1, 3 (July 1971): 291–306.

2. S. N. Eisenstadt has recently called attention to this disturbing trend in “Culture and Social Structure Revisited,” International Sociology 1, 3 (September 1986): 297–320.

3. Jon Elster, Making Sense of Marx (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 5–6. The debate is thoroughly vetted in the essays collected in John O’Neill, ed., Modes of Individualism and Collectivism (London: Heinemann, 1973).

4. Much the same idea is captured in Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman’s epigram, “Society is a human product.… Man is a social product” (The Social Construction of Reality [Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967], 61). Also see Robert Grafstein, “The Problem of Institutional Constraint,” Journal of Politics 50, 3 (August 1988): 577–99.

5. Marshall Sahlins, Historical Metaphors and Mythical Realities: Structure in the Early History of the Sandwich Island Kingdoms (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1981), cited in Sherry B. Ortner, “Theory in Anthropology Since the Sixties,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 26, 1 (January 1984): 126–65, quote on 156.

6. This example is offered by Harry Eckstein, who terms this “pattern-maintaining change” (“A Culturalist Theory of Political Change,” American Political Science Review 82, 3 [September 1988]: 789–804; quote on 794).

7. As Kenneth Burke formulated it, “A way of seeing is always a way of not seeing” (Permanence and Change [New York: New Republic, 1935], 70).

8. This point is elaborated in W. G. Runciman, Social Science and Political Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963), Chapter 8.

Chapter 1

The Social Construction of Nature

We begin our examination of the viability of ways of life with a bedrock question: What determines the models people use of human and physical nature? Ideas of nature, whether physical or human, we argue in this chapter, are socially constructed. What is natural and unnatural is given to individuals by their way of life.

To say that ideas of nature are socially shaped is not to say that they can be anything at all. Yet this is the relativist charge that is often leveled at those (the “strong programme” in the philosophy of science, for example, and the grid/group approach to the sociology of perception1) who have tried to account for the social construction of perception. “Okay, go and jump in front of the train,” say the relativity rejectors, believing themselves to have achieved some sort of refutation when the relativist declines the challenge. But of course, no one is saying that perception is completely fluid, only that it is not completely solid. Rather, ideas of nature are plastic; they can be squeezed into different configurations but, at the same time, there are some limits. The idea of nature that would have us all leaping in front of trains is outside of these limits, that is, it is not a viable idea of nature.

This debate between realists (as they like to call themselves) and relativists (as they get called) is a pernicious trivialization of a serious issue and the time is long overdue for its replacement by a notion—we will call it constrained relativism—that firmly rejects both these polarized extremes. The difficulty, of course, lies not in saying this but in propounding the concepts to go with it, concepts robust enough to avert the deterioration of the debate to the dreary jump-in-front-of-the-train level. This, we claim, is precisely what our theory of sociocultural viability does.

Five Myths of Nature

In the course of studying managed ecosystems—like forests, fisheries, and grasslands—ecologists discovered that the interventions of the managing institutions in the ecosystems were wildly heterogeneous. That is, different managing institutions, faced with exactly the same sort of situation, did very different things (some, for instance, started spraying the forest with insecticide, others stopped). Whereas trees and bud-worms and other natural components of the ecosystem could be relied on to behave fairly consistently, the managing institutions could not. Yet the behavior of the institutions was not completely random. Though they did different things, they did not do just anything, and the ecologists discovered they could account for the diversity of institutional response by introducing into their analysis a number of myths of nature.2

These myths of nature are the simplest models of ecosystem stability that when matched to the different ways in which the managing institutions behave, render those institutions rational. However, unlike the explicit models that scientists usually deal with, these models are seen by those who hold to them as being built from largely unquestioned assumptions.

The myths of nature, in consequence, are both true and false; that is the secret of their longevity. Each myth is a partial representation of reality. Each captures some essence of experience and wisdom, and each recommends itself as self-evident truth to the particular social being whose way of life is premised on nature conforming to that version of reality.

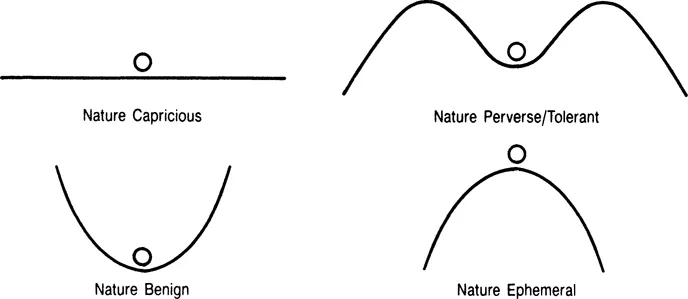

There are five possible myths of nature: Nature Benign, Nature Ephemeral, Nature Perverse/Tolerant, Nature Capricious, and Nature Resilient. In order to simplify the exposition of the five myths, we leave the description of Nature Resilient, a sort of “meta-myth” that claims to subsume the other four, until later in this chapter. Each of the other four myths can be represented graphically by a ball in a landscape (Figure 2).

Nature Benign gives us global equilibrium. The world, it tells us, is wonderfully forgiving: No matter what knocks we deliver, the ball will always return to the bottom of the basin. The managing institution can therefore have a laissez-faire attitude. Nature Ephemeral is almost the exact opposite. The world, it tells us, is a terrifyingly unforgiving place and the least jolt may trigger its complete collapse. The managing institution must treat the ecosystem with great care. Nature Perverse/Tolerant is forgiving of most events but is vulnerable to an occasional knocking of the ball over the rim. The managing institution must, therefore, regulate against unusual occurrences. Nature Capricious is a random world. Institutions with this view of nature do not really manage or learn: They just cope with erratic events.

Figure 2. The four primary myths of nature

Nature Benign encourages and justifies trial and error. As long as we all do our exuberant, individualistic things, a “hidden hand” (the uniformly downward slope of the landscape) will lead us toward the best possible outcome. But such behavior becomes irresponsibly destructive if nature is ephemeral. Nature Ephemeral requires us to set up effective sanctions to prevent this sort of thing from happening, to join together in celebration of incuriosity and trepidity. Of course, the fact that we are still here, despite all our perturbations, would seem to make this myth a nonstarter. We need only to introduce a little friction into the landscape, however, for the ball to stay where it is, as long as we all hold our collective breath. This is the perfect justification for those who would have us all living in those small, tight-knit, decentralized communities that respect nature’s fragility and make appropriately modest demands upon it.

Whereas Nature Benign encourages bold experimentation in the face of uncertainty and Nature Ephemeral encourages timorous forbearance, Nature Perverse/Tolerant requires us to ensure that exuberant behavior never goes too far, that the ball remains within the zone of equilibrium. Neither the unbridled experimentation that goes with global equilibrium nor the tiptoe behavior appropriate to global disequilibrium can command moral respect here. Rather, everything hinges upon mapping and managing the boundary line between these two states. Certainty and predictability, generated by experts, become the dominant moral concern.

With Nature Benign, Nature Ephemeral, and Nature Perverse/Tolerant, learning is possible, though each disposes its holders to learn different things (and, thereby, to construct different knowledges). But in the flatland of Nature Capricious there are no gradients to teach us the difference between hills and dales, up and down, better and worse. Life is, and remains, a lottery. It is luck, not learning, that from time to time brings resources our way.

These four thumbnail sketches (and the fifth to be dealt with presently) show that it is our institutions that supply us with our myths and, in so doing, systematically direct our attention toward certain features of our environment and away from others. Nature Benign is the myth that readily recommends itself to the competitor—the individualistic advocate of the free market—while Nature Perverse/Tolerant is the hierarchist’s myth, Nature Ephemeral the myth of the egalitarian, and Nature Capricious the myth that reconciles those who find themselves squeezed out from all these institutional forms to their fatalistic ineffectuality.

The five myths of nature, derived from the work of ecologists, closely coincide with the ideas of nature (introduced in “Sociocultural Viability: An Introduction” and explored more fully in the next chapter), which we have deduced by asking how nature would have to be conceived for our five ways of life to be livable. To recap quickly, we suggested that for fatalism to be a viable way of life, nature must be constructed to appear as a lottery-controlled cornucopia. For egalitarianism to be a viable...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Sociocultural Viability: An Introduction

- PART ONE THE THEORY

- PART TWO THE MASTERS

- PART THREE POLITICAL CULTURES

- Bibliography of Cultural Theory

- Index