![]()

PART ONE

The Forgotten Interior

![]()

1

The Interior and the Argentine Nation

Argentina in the early part of this century was one of the most affluent nations in the world. Its per capita income was the highest in Latin America and higher even than in several Western European countries.1 In the half-century before the Great Depression, Argentina had one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world, received and assimilated millions of European migrants, and enjoyed a stable democracy.

In the last six decades, the Argentine economy has grown erratically, with long periods of stagnation and recession. Since the mid-1970s, Argentina's per capita income has actually fallen and is now less than that of Chile or Malaysia and scarcely higher than that of Thailand or Colombia. Before 1930, Argentina received more European immigrants than any country except the United States, but now Argentines are emigrating by the thousands. Since 1929, no civilian president has finished his or her constitutionally mandated term in office; most have been overthrown by the military or replaced through a fraudulent election. Military dictatorships, each more brutal than the one before, have alternated with civilian governments. Under both civilian and military governments, corruption and incompetence seemed to grow without end. By the end of the 1980s, self-doubt and pessimism had engulfed the nation.

Economic decay has been most acute in Argentina's interior—the part of the country that lies beyond the fertile and well-watered grasslands known as the pampas. The current president has begun a thoroughgoing liberalization of the economy that has produced four years of price stability and perhaps the new era promised so often in the past. Nevertheless, these policies have exacerbated the economic plight of the interior. The collapse of the economies of the interior now threatens the fiscal and political stability of the national government.

Argentina's spectacular failure has attracted the attention of hundreds of scholars, both within the country and without. Some have remained baffled by Argentina's failure. Simon Kuznets used to say that there were only two countries whose development path economic theory could not explain, Japan and Argentina (Waisman 1987, 4). The problem for most scholars, however, is an overabundance of explanations from which to choose rather than a lack of them. The most common explanation blames policies pursued by Juan Domingo Perón, president between 1946 and 1955 and again in 1973 and 1974. Others have argued that the root of the problem is the policy of import substitution industrialization pursued by every government from the 1930s until the present administration. Still others blame the country's economic woes on the political stalemate that has jammed the decision-making process. Other culprits indicted in the literature are the labor movement, which is said to have had too much power, the disastrous drop in export demand after 1929, the country's colonial heritage, its woefully misguided and costly foreign policy, its supposedly precapitalist agriculture, its dependence on the First World, and its antidevelopment culture. There is at least a grain of truth in each of these explanations, but no single explanation will serve. As Jorge Schvarzer put it, Argentina's "failure on such a grand scale precludes any single undisputed explanation" (1992, 180; see also Ranis 1986, 150). The purpose of this book is not primarily to dispute any of these common explanations, but it is to add to the list of explanations.

This book is the first systematic attempt to relate the interior's backwardness to the national economy's failure. As subsequent chapters will make clear, to ignore the interior risks disregarding an important—and perhaps crucial—part of the story. Without a clear conception of the place of the backward interior in the national economy and polity, the search for a solution to Argentina's problems is necessarily handicapped.

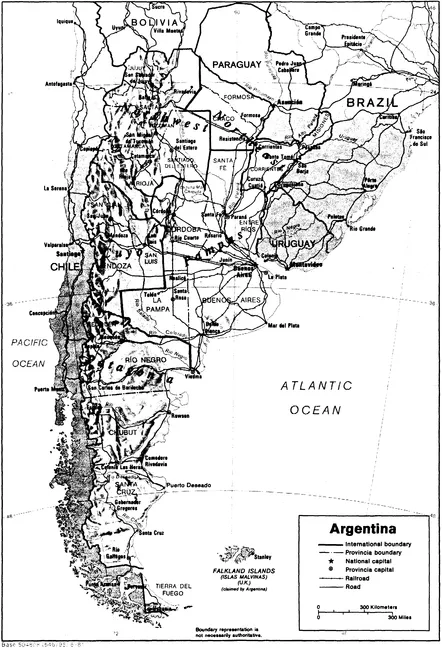

The Invisible Interior of Argentina

The interior of Argentina contains 70 percent of the nation's land and 31.5 percent of its population. It would have a much larger share of the population—perhaps more than half—except that millions of people from the interior were expelled by poverty and unemployment from their native provinces and moved to the pampas in search of a better life.2 The interior was almost entirely bypassed during the pampas' half-century of glory that ended in 1930. Parts of the interior were worse off at the end of the boom than at the beginning. During the sixty-five years since 1930, the interior has remained mired in poverty.3 The stagnant interior has thus not been a part of the solution to Argentina's problem but instead has been part of the problem.

Despite the demographic and economic importance to the Argentine economy of the interior, it remains neglected and ignored, invisible to most social scientists and politicians alike. It is excluded from the popular images of the country, both within and outside Argentina.4 Information about the

interior is available, as the lengthy bibliography of this book attests. The student of the interior, however, must be willing to look on dusty shelves in obscure libraries to find very much. Most analyses of Argentina's problems do not mention the interior at all. The few authors who do refer to the interior dismiss its importance, often using the cliché, "pockets of poverty."5 This gives the false impression that poverty in the interior is isolated and widely scattered rather than systemic and ubiquitous. Without a proper understanding of the scope and sources of the interior's poverty, and the effect of the interior's poverty on the entire nation, policy makers will find economic progress elusive.

The Interior over the Years

The notion that the backward interior holds back the rest of the nation has deep roots in Argentine thinking, although until very recently it was fashionable to hold the opposite view. Toward the middle of the last century, Domingo Sarmiento (who later became president) and Juan AJberdi were leaders of a group of intellectuals and politicians who formulated a strategy for the economic and social development of Argentina.6 In their eyes, the interior was backward and barbaric because it was the product of sixteenth-century Spain, indigenous peoples, and black slaves (Sarmiento 1868, 11, 24; Alberdi 1984 [1852], 81-88). The people of the interior were lazy and had no aptitude for science, technology, or industry. The pampas, on the contrary, were civilized and progressive because they were peopled by Europeans, most of whom arrived in the nineteenth century. Sarmiento believed that education could change the mentality of the interior. Alberdi disagreed; he favored more immigration from Europe and an elite democracy that excluded the poor.

Until 1880, a great fratricidal struggle divided the interior from the pampas. For a time it seemed that the interior might even assert its hegemony over the pampas. Nevertheless, much of the interior was still without human settlement or populated by unassimilated indigenous peoples. There were a few pockets of development, but the economy and society in much of the interior had hardly changed in centuries. By the end of the nineteenth century, on the other hand, the spectacular ascent of the pampas was well under way. The overwhelming preponderance of the pampean economy allowed the region to politically dominate the interior.

The challenge facing Argentina at the turn of the century was no longer to subdue the interior but instead to acculturate the flood of immigrants that had descended upon the country. Sarmiento and Alberdi's hopes for immigration from Europe had been fulfilled. The newcomers, however, were widely perceived as culturally inferior, materialistic, and slow-witted. Nostalgia for the old days gave birth to a new national mythology of the gaucho, the Argentine cowboy. Sarmiento and Alberdi had painted the rural mestizo as a barbarian. Now he was idealized as the epitome of nobility, generosity, loyalty, bravery, skill, honesty, and gallantry.7 Rural Argentina, as the national repository of traditional values, was rehabilitated. The gaucho myth and the glorification of traditional values represented rural Argentina, not just the interior, but the interior shared in the good press. If the interior's image now had a rosy glow, it did not mean that average Argentines, the large majority of whom now lived on the pampas, thought much about it. The action was on the pampas, and the rest of Argentina faded from the national consciousness.

The 1920s and 1930s were marked by political struggles that once again thrust the provincial question into the public's consciousness. In the 1920s, the national government was in the hands of a political party whose political base was on the pampas. The president attempted to win allies among the disaffected members of the interior's elites and, failing that, to impose federal control over provincial governments. The uproar that these aggressive tactics provoked led to the country's first successful coup d'état. The general who headed the coup was from Salta, and conservatives from the interior continued to dominate the national government until the early 1940s. As opposition parties struggled for control over provincial governments, the rancorous antagonism between the interior and the pampas continued to divide the nation.

The economic decline of the 1930s made painful the country's dependence on Europe, which until then had brought such prosperity. Especially galling was the Roca-Runciman Treaty, a bilateral trade agreement between Argentina and Great Britain that most Argentines viewed as humiliating. The villain in the popular perception of this affair was the pampean oligarchy, whose markets for beef and grain the treaty protected. It was felt that they had willingly submitted to British dictates to protect their own interests but, in the process, had betrayed the rest of the country. Intellectuals from the left wing, such as Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz, and from the right wing, such as Leopoldo Lugones and the Irazusta brothers, blamed Argentina's woes on foreign domination in a way that often poured salt on the old wounds that divided the pampas from the interior.

The provincial question was thrust even more vigorously into public awareness in the 1940s. Perón's strident nationalism was a major part of his appeal to voters. He portrayed Argentina as the innocent victim of the rapacious developed countries. The enemy was the pampean oligarchy, which had betrayed the country to British imperialism. It was an easy step to picture the interior as the victim of the rapacious pampas. Perón never missed a chance to show his concern for the provinces. Indeed, he first became a well-known public figure through his efforts to organize relief for earthquake victims in San Juan. He toured the interior often and dramatically increased the national government's resources spent in the interior. Support from the interior was crucial to Perón's election in 1946, and as the years went by it played an increasingly important role in the Peronist movement.

By the 1960s, the notions of external and internal dependency had become almost universal among intellectuals in Latin America and had found considerable sympathy in Argentina. The belief that the principal obstacle to the interior's prosperity was the pampas—or the national government that was a captive of pampean interests—was now firmly estab- lished and continued to dominate political discourse through the 1970s and 1980s.8 The military government between 1976 and 1983 fostered a number of economic development projects in the interior in order to protect the border regions from land-hungry neighbors. The Radical government that followed repeatedly used notions of internal and external dependency to justify its policies. It increased subsidies to private businesses and governments in the interior and began to implement a scheme to move the capital of the country to Patagonia.

The liberal ideas that are sweeping Latin America today and guiding the present government of Argentina have traditionally been antithetical to notions of dependency. The idea that the interior has been exploited by the pampas has been increasingly challenged both in the popular press and in scholarly monographs. Nevertheless, my argument that the underdevelopment of the interior is a major obstacle to national economic progress, and that it is the interior that is draining the pampas of resources rather than the other way around, is still at odds with the preponderance of scholarly and popular opinion in Argentina.

The Prairies and the Pampas; the South and the Interior

Argentina in 1930 seemed to have much in common with Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and even the United States. They all had large amounts of fertile land and thus a land-surplus rather than a labor-surplus economy. They all prospered by selling grain, meat, and/or wool to Europe. They enjoyed a temperate climate, were mostly populated by recent European migrants, and had a mostly European cultural tradition. Nevertheless, the other "new countries" continued to grow after the Great Depression, while Argentina stagnated. Argentina's failure to keep up almost automatically frames the puzzle of Argentina's stagnation in a comparative perspective. The notion that Argentina's experience bore important similarities to those of the other "new countries" first appeared in the early years of this century. In the last thirty years, as Argentina's arrested development became ever more conspicuous, an avalanche of scholarly works on this theme has appeared.9

A stock phrase in this literature is "the prairies and the pampas." The vast grassy plains of North America were settled at the same time as the pampas. The climate, the crops, the technology, and even the markets were largely the same. What is striking about the "new country" literature is not the stress on the obvious similarities between the prairies and the pampas but rather the lack of almost any mention of the equally obvious similarities between the backward interior of Argentina, especially the Northwest, and the South in the United States.

Both the U.S. South and the Argentine Northwest are regions that initially played a preponderant role in their nation's development but later fell upon hard times. For both, economic stagnation followed military defeat at the hands of the more modern part of the country. Both, at the time of their defeat, used modes of labor procurement that relied on coercion and violence and continued to use premodern modes of labor organization well into the twentieth century. In the interior of Argentina and in the Deep South, a large share of the laboring population was nonwhite, whereas the economic elite was of European descent. In both regions, a small minority owned the bulk of the good agricultural land and the majority of the agricultural population was landless. In both regions, agriculture was the economic base and a single crop dominated the economy. The backward and stagnant economy of both the South and the interior produced a backward political culture centered on the patron-client relationship and the exclusion of a large share of the population from the democratic process. Both regions played a role in the national political arena that was out of proportion to their demographic and economic strength. Both regions harbored deep anger and resentment, blaming their problems on the economically dominant regions.

The U.S. South broke loose from its backwardness and poverty, but the Argentine Northwest has not. In both regions at about the same time the national government imposed agricultural reform that began to revolutionize the economy, shaking loose a flood of dispossessed migrants in the process. Roosevelt's Agricultural Adjustment Acts (especially the second in 1938) and made sharecropping unprofitable. The national minimum wage (also enacted in 1938) drew labor out of agriculture. These laws jolted the Southern economy to its foundations. The Statute of Perón (first enacted in 1944 and subsequently amended several times) looked as if it might have a comparable effect on the Northwest, but it was not vigorously enforced, especially after Perón was deposed. At any rate, the South was well endowed with agricultural resources and had other options beside cotton, especially soybeans. The Northwest, with a far more limited agricultural resource base, has been unable to diversify much beyond sugar.

The South also had an important manufacturing sector on which to build and the capital to finance industrial growth. Manufacturing in the South, although always outclassed by Northern industry, has been substantial since the colonial era. In the early twentieth century, the South had several important industries, especially furniture, textiles, tobacco processing, and steel. In the second half of the century, many other industries developed. To this day, manufacturing in the Argentine Northwest is largely sugar refining; most other industries exist only because of heavy subsidies. Perhaps most important of all, the South is part of a country that is far richer than Argentina. By the mid-twentieth century, the barriers to the import of capital from the North had been weakened, and a flood of capital allowed the region to begin its spectacular ascent. These contrasts and similarities between the South and the Northwest illuminate the difficulties facing the Argentine interior and suggest hypotheses that has gu...