- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A voice on late night radio tells you that a fast food joint injects its food with drugs that make men impotent. A colleague asks if you think the FBI was in on 9/11. An alien abductee on the Internet claims extra-terrestrials have planted a microchip in her left buttock. 'Julia Roberts in Porn Scandal' shouts the front page of a gossip mag. A spiritual healer claims he can cure chronic fatigue syndrome with the energizing power of crystals . . . What do you believe? Knowledge Goes Pop examines the popular knowledges that saturate our everyday experience. We make this information and then it shapes the way we see the world. How valid is it when compared to official knowledge and why does such (mis)information cause so much institutional anxiety? Knowledge Goes Pop examines the range of knowledge, from conspiracy theory to plain gossip, and its role and impact in our culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Knowledge Goes Pop by Clare Birchall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Know It All

Conspiracy theory, alien abduction narratives, astrology, urban legends, self-help rhetoric, gossip, new age practices. It is so tempting, when someone asks what popular knowledge is, to respond by listing some examples. But this doesn't really answer the question; it merely illustrates an answer that remains absent. It is easier to point to examples already penetrating everyday life than to come up with a list of hard-and-fast characteristics that can always be disputed. I don't intend this book to become a checklist that people can reference in order to ascertain the 'popular knowledge-ness' of one discourse or another. I recognize that there are as many differences as similarities between various forms of popular knowledge and that discourses will slide imperceptibly between the 'unofficial' and 'official', between the 'legitimate' and 'illegitimate', between the 'high' and 'popular'.1 Though singular and unique, I do think that knowledges like the ones I began by listing can usefully be thought of on a continuum of popular cognitive practices that deny scientific rationalism and justified true belief as the only criteria for knowledge. In thinking of this continuum, I will be able to make a meaningful engagement with questions regarding the status of knowledge in general.

Knowledge-Scape

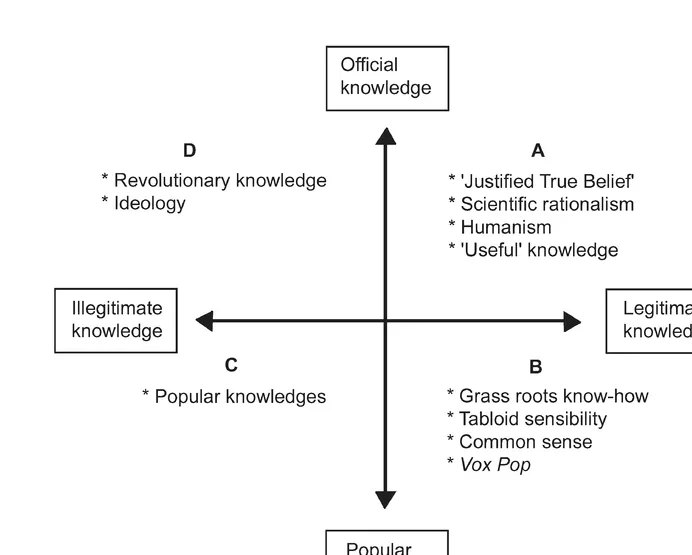

While I will ultimately challenge the terms outlined in Figure 1,I want to use it as a springboard for thinking about the status of knowledge as it is theoretically configured, experienced, or presented to us in everyday encounters. It might be helpful to think of this diagram as a visual representation of an historically rooted debate in the 'West' about different kinds of knowledge.

Lingering at the top right-hand corner of Figure 1 (Position A) lies justified true belief. This formulation of knowledge can be traced back to Plato's Theaetetuswritten in 360 BCE in which Socrates is in dialogue with Theaetetus about the nature of knowledge. The logic of the 'justified true belief' account is as follows (S delineates the knowing subject, and pthe proposition known). Sknows that pif and only if:

Figure 1 Knowledge-scape

- pis true;

- Sbelieves that p; and

- S is justified in believing that p.

If something is false (say, for example, the proposition that Prince Charles wrote this book), we cannot know it: this would be to know no thing (nothing). So, the proposition has to be knowable as true. Of course, we can believe something without necessarily knowing it; it only becomes knowledge if we can establish its truth and justification. Epistemologically, belief does not refer to the idea of having faith, rather it indicates our assent to a statement's truth. Much attention in the dominant epistemological traditions has been given to the question of how justification can be ascertained and, latterly - since Edmund Gettier (1963) showed justified trvie belief' to be insecure or incomplete as a definition - what other criteria have to be in play for knowledge to be knowledge. Despite the many challenges to this definition of knowledge, I have situated 'justified true belief' as an example of the 'official' and legitimate' because of the force it has had and continues to have in common sense' understandings of knowledge.

Below the horizontal dividing line of Figure 1 (positions B and C) lie discursive phenomena more closely associated with the popular (whether this be in the sense of populist or mass circulation and participation).That which, albeit provisionally, falls into the category of 'legitimate' and popular (position B) can be traced back at least to the challenge put forward in the English Civil War to the divine right of kings, and, latterly, to the drive for universal suffrage. Whereas for Plato, those ideas that couldn't fulfil the criteria of knowledge were branded and devalued as opinion or doxa, in the tradition of what we could call democratic or Christian socialism, and populism of all political ilks, the knowledge of the people' is valued as being untainted by high office and therefore closer to truth. Such ideas see 'the people' and their knowledge as legitimate (morelegitimate, even, than those in corrupting positions of power).

Broadly speaking, tabloids from both ends of the political spectrum (I am thinking primarily of the British press in this instance) such as the Mirrorand the Sun,champion the 'man on the street' over politicians, large corporations and, more ambivalently, the law (particularly EU law, which is fashioned as being remote or insensitive to the concerns of the British people).This rhetoric, privileging the individual over the corporation or state, can be seen reflected in a surge of populist politics from the Conservatives and New Labour in contemporary Britain, in the admonitions of the 'nanny state' and advocacy of personal autonomy and choice. Elsewhere, populists who peddle their various politics in the name of the people include Australia's Pauline Hanson, Winston Peters in New Zealand, Jean-Marie Le Pen in France, Carl I. Hagen in Norway, William Jennings Bryan, Huey Long, Paul Wellstone, Howard Dean and John Edwards in the United States, Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar, Silvio Berlusconi in Italy, Jörg Haider in Austria, Lula in Brazil, Preston Manning in Canada and Hugo Chavez in Venezuela.2

Under the category of the legitimate' and popular, we could also situate 'common sense'. Usually notions claimed as unmediated, self-evident common sense (such as the possibility of agency the difference between the human and inhuman, or what constitutes truth) are filtered down from humanism and are in actual fact highly ideological and situated. Such ideas have legitimacy in their own terms with regards to the dominant ideology and are popular in their standing. That is to say, they are widely disseminated and, in general, support the official ideas of that society (even while they might be voiced with different, more individualist, Concerns).

Position C in the bottom left-hand corner of Figure 1 is traditionally ascribed to the phenomena that I am interested in for this book (though in some appropriative accounts that praise popular knowledges, such phenomena has been ascribed position B). Under this category fall all those knowledges that traditionally have not counted as knowledge at all: knowledges of an uncertain status; knowledges that have not been verified; knowledges that are officially discredited (for different reasons) but which still enjoy mass circulation. These would include gossip and conspiracy theory (the two main examples I consider in this book), but also those knowledges I began this chapter by listing. With regards to a definition, I will postpone any attempt until later and as I will have mvich more to say about this realm, I will move on swiftly to position D.

The top left-hand corner of Figure 1 is perhaps the most slippery position of all, or at least the one that exposes the instability of all the positions. The clearest example of a knowledge that is official yet illegitimate arises from Marx's conception of revolutionary knowledge. Knowledge that the working class is exploited is part of the official logic of capital and yet the expression of this knowledge is branded illegitimate by the ruling class. Exploitation is both part of the smooth running of industry, say, but it cannot be seen as a 'legitimate' idea to know because this might sanction resistance and revolution. Inequality and exploitation are 'legitimate' and official (position A) for those in power, but knowledge ofthem is framed as illegitimate in order to maintain the status quo. Position D, then, is the space of ideology. Here, discourses such as racism can be institutionalized (and official) and yet remain unacknowledged (illegitimate). Equally, in a slightly different formula, discourses like racism can be institutionalized (and official) and yet be exposed, dismissed and deemed illegitimate by another discourse, say liberalism or human rights. Either way, such discourses are positioned as illegitimate andofficial.

Figure 1 is something of a ruse (as is the as-yet unseen Table 1). I am not usually a fan of diagrams and tables because of their rigid appearance. The positions in Figure 1 are far from fixed and are dependent on external, contingent factors. All of the knowledges in position A, for example, could equally be in position D. What is illegitimate knowledge from one political position could be legitimate for another, depending on what legitimating criteria is drawn upon. I have, however, tried to provide a diagram that expresses the dominant ideology in the 'West' with regards to knowledge culture. The interventions that I will summarize and draw upon below arise from those disciplines that I feel to be the most helpful in preparing the ground to consider a particular dynamic evident in the diagram; namely, the tension between positions A and C. That is, I am interested primarily in questioning the relationship between knowledge that holds an officially 'legitimate' status and that which is considered to be of 'illegitimate' and popular status (at least from the vantage point of the 'official'). This is the tension that will organize the concerns of this book, though the other positions in Figure 1 will never be far from view and will occasionally take centre stage.

Knowledge Now

When thinking through the contemporary conditions of popular knowledge, we would do well to remember that the exchange of knowledge on a mass level is nothing new. The rise of the print medium and of general literacy ensured a degree of knowledge exchange on a wide scale. Locally, of course, 'illegitimate' knowledges have always been exchanged.Yet, the velocity and scale of knowledge exchange in the Internet age is unique.Those local, 'illegitimate' knowledges now enjoy mass participation. But it is not only the speed and scale of dissemination that marks this situation out as particular to the late twentieth, early twenty-first century. The whole question and context of knowledge into which popular knowledge arrives is situated within an epistemological conjuncture. Moreover, the ground into which popular knowledge arrives determines the way it will be configured, what role it has to play, and what will be challenged by that arrival. The questions raised by popular knowledge are unique today because of the particular way in which the ground of knowledge is configured. We could schematize part of that epistemological conjuncture as in Table 1.

The linear construction of this table is misleading, not only because of the interdependent and porous boundary between each knowledge but because there is no intrinsic order or hierarchy of importance to these knowledges (although we are often led to believe there is). It also disguises the way in which definitions are disputed within particular discourses, let alone between them. Moreover, this table is by no means exhaustive. We could, for example, add religious knowledge and scientific knowledge, and no doubt the list could go on in an endless, somewhat Borgesian, taxonomy. It is not my intention to attempt such work here, but this table should at least hint at the way in which new definitions of knowledge have both symbolic and material repercussions. When the humanities' concept of knowledge is symbolically displaced by that proposed by the knowledge economy, for example, the institution the humanities concept is attached to – the university – in turn has to adapt to that challenge (by being forced to respond to market pressures).This symbolic displacement has very real effects on the experience of higher education.

Let me look at this effect ill the UK more closely (although similar policies concerning the knowledge economy have been proposed by most governments ill the 'developed' world). The role of the university is integral to the vision of a successful knowledge driven economy as outlined in the 1998 Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) White Paper, Our Competitive Future: Building the Knowledge Driven Economy.It provides incentives for universities to develop links with businesses, to aid what is called knowledge transfer'. The signifier 'university' is borrowed by the university for industry' – an idea that has lead to the creation of a public-private partnership whose services are currently delivered by Learndirect, The emphasis here is on the (often online) delivery of business and IT-oriented skills. The focus is on the acquisition of tangible content, rather than the experience of learning and the development 'of transferable cognitive skills. The development of this alternative 'university' implies that the traditional university is somehow ill equipped to cater for the new knowledge economy. In fact, higher education centres have been working

| Form of Knowledge | Site of Production and Circulation | Means of Legitimation | Criteria |

| Knowledge economy | Industry; commerce; government policy; the economy; economics; managementtheory; sociology; the media | Free market economy; neoliberal/ neoconservative capitalism; appeal to new and inevitable' economic phase; the media | Commercial use and profitability; design and innovation; tacit knowledge with codified technical knowledge |

| Knowledge within the humanities | The university | Appeals to the university'; university endorsed awards; grants and bursaries; tradition | Intellectual use; internally established measures such as reason and scientific rationalism; that which yields cultural capital |

| Popular knowledge | Relatively unofficial and unregulated sites (e.g. Internet; face-to-face interaction) | Insider knowledge; paradoxical reliance upon official' accreditation; degree of risk or perseverance required to obtainin formation | Whether it has been dismissed, excluded or suppressed by any of the above. |

| Indigenous knowledge | Localized sites; home' | Tradition; culture; claims on the land | Repetition; that which is revered; often dogmatic; spiritually or agriculUirally useful |

with Learndirect to deliver these courses but there are still indications that the traditional degree programme is considered to be out of step with the needs of industry. Some of this is valid criticism, and many universities have attempted to address these problems through work placement schemes and modularization But there are many reasons why academics are resisting this change in the focus of degree programmes and the aims of higher education institutions. These range from political objections (many disciplines are based on critiquing rather than supporting commercial culture), to pedagogic concerns (over what effects the corporatization of higher education has on teaching). Straight away we can see an incompatibility arising between the first knowledge in our table and the second.

It is not that the humanities' definition of knowledge is whollydifferent from knowledge that holds such a premium in the knowledge economy if, for the sake of argument, we take the former to be a philosophically derived definition of knowledge as a belief which is verified as far as possible and is subject to conditions of fallibility (the 'justified true belief' model). After all, scientific methodology, which is central to the knowledge economy, is based on such principles set forth by scientific rationalism: the idea that everything is rational and explicable through empirical observation and the consequent deduction of laws. However, the humanities are not generally interested in the economic utility of its knowledge (except in as much as the production and publication of ideas are pretty much essential to the furtherance of an academic career these days). Also, the objectsof knowledge are very different between the knowledge economy and the humanities. The former is interested in scientific, technical, service-based, brand-oriented knowledge, and the latter in knowledge about history, culture and knowledge itself. These are not mutually exclusive interests (if they were, I would not be writing about them here – and, in fact, the cultural inflection of commerce has been widely commented on), but businesses take historical and cultural factors into consideration when developing or marketing a brand or product primarily in order to gain a competitive edge in the market. Knowledge in the humanities by contrast is valued for being intellectually rather than economically 'useful'.

Although the DTI White Paper claims that the knowledge economy 'is not just about pushing back the frontiers of knowledge' but also the more effective use and exploitation of all types of knowledge in all manner of activity', it is not clear how knowledges within the humanities, some of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Know It All

- 2 Just Because You're Paranoid, Doesn't Mean They're Not Out to GetYou

- 3 Cultural Studies on/as Conspiracy Theory

- 4 Hot Gossip: The Cultural Politics of Speculation

- 5 Sexed Up: Gossip by Stealth

- Conclusion: Old Enough to Know Better? The Work of Cultural Studies

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- Index