- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2018. This book captures the self-confident spirit that characterizes Kenya and provides unique insights into how this nation of contemporary Africa is faring in its continuing quest for prosperity, focusing on the contemporary period, beginning with the rise to power of President Daniel arap Moi in 1978.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kenya by Norman Miller,Rodger Yeager in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Colonial Legacy

Beginnings

Eastern Africa may very well be the birthplace of humanity.1 Some of the earliest predecessors of Homo sapiens lived around the lakes and in the lush, game-filled savannas of the Great Rift Valley. During the late 1950s and 1960s, the remains of Zinjanthropus boisei and Homo habilis were discovered at Olduvai Gorge in northern Tanzania. These two species lived during the Lower Pleistocene epoch, between three million and one million years ago. More recently, a probable ancestor of these protohumans was uncovered near Lake Turkana in Kenya. Pioneered by the Leakey family of prehistorians, the search continues for still older evolutionary progenitors.

As far as can yet be determined, the human history of Kenya began about ten thousand years ago, when isolated communities of Khoi-San hunters and gatherers settled in the Rift Valley. These movements were followed in the first millennium B.C. by migrations of Cushitic-speaking pastoralists from southern Ethiopia and in the first millennium A.D. by a much larger influx of Bantu-speaking cultivators from western Africa. The initial settling of Kenya was completed between the tenth and the eighteenth century in a series of migrations from the Sudanic Nile region.2

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, many of the socioeconomic and cultural features of modern Kenya had taken basic shape. The dry reaches of the north were inhabited by widely scattered populations of seminomadic pastoralists. In the south, pastoralists and cultivators bartered goods and competed for land as long-distance caravan routes penetrated the territories of both from the Kenya coast to the kingdoms of what is now Uganda. A mixing of Arab, Shirazi, and coastal African cultures had given rise to an Islamic Swahili people trading in a variety of up-country commodities, including slaves. Networks of commerce linked inland societies with the coast. From their home territory in south-central Kenya, Kamba elephant hunters mounted long-distance expeditions in search of ivory. To the west, Kikuyu farmers overcame their hostility toward free-ranging herders in the interest of a sophisticated trade with the pastoral Maasai in cattle, iron goods, and items obtained from coastal merchants.3 Commerce in the vicinity of Lake Victoria focused on skins and hides, salt, forged iron products, and beeswax.

Much of this early interaction among peoples was stimulated by the impact of Arab and Shirazi entrepots including Kilwa Kisiwani, Pemba, Zanzibar, Gedi, Malindi, and Mombasa. Galleon-like dhows sailed with the monsoon winds to and from eastern Africa, transporting large varieties of imports and exports. Reaching Kenya were salt, metal goods, beads, furniture, tools, and cloth. Carried away were slaves, ivory, dried fish, tortoise shells, and building materials. As this traffic increased in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, key trading ports became self-governing city-states complete with merchant houses, military establishments, and civil administrations. Two important cultural nuances resulted from this activity. First, Kiswahili emerged as eastern Africa’s major language of trade. Originating in a combination of Bantu and Arabic dialects, Kiswahili facilitated economic relations and, as a lingua franca, eventual European exploration, religious conversion, and colonization from the coast to Lake Victoria and beyond. Second, a rich coastal civilization—the Omani-Swahili—arose from the combination of African and Arabian Gulf traditions to form distinct patterns of architecture and art, poetry, cuisine, manners, and social customs.4 Chief among the latter was a strong mercantile ethic.

In 1498, a new era began for coastal eastern Africa with the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Trade and conquest were the twin objectives of the powerful Portuguese, and within a short time they dominated the western Indian Ocean littoral. Fort Jesus, with its imposing ramparts and turrets overlooking Mombasa harbor, was completed in 1593 to afford the Portuguese military control over the coast and to eliminate the commercial hegemony of the resident Omani Arabs. Intended primarily to establish and defend resupply points for ships en route to the Orient, Portuguese suzerainty was oppressive but relatively short. Under the command of the imam of Oman, Saif bin Sultan, Omanis took Mombasa in 1698 and captured Pemba and Kilwa a year later. By 1729 they had expelled the Portuguese from all settlements north of the Ruvuma River, which later formed the northern boundary of Portuguese Mozambique.

Although their tenure was brief and disruptive, the Portuguese contributed significantly to Kenya’s food crops and coastal technologies. They probably brought the first maize, potatoes, and cassava root to eastern Africa.5 They also exercised considerable influence over local naval design, navigation and sailing techniques, and modes of warfare. Still, the Kenya coast had nurtured an Islamic African-Arabian civilization before the Portuguese came, and when they left it returned to Islamic control. The interlopers represented an alien, Christian culture that subsequent Muslim rulers took particular care to eradicate.

Having expelled the Portuguese, Saif bin Sultan returned to Oman after appointing Arab governors over the coastal city-states. Several of these regimes later fell under the sway of the governor of Mombasa, Muhammed bin Uthman al-Mazrui, head of the powerful Mazrui dynasty Appointees from this family soon gained dominion over much of the coast, ruling as independent sultans while offering ceremonial allegiance to the Omani imam and often quarreling among themselves for influence and wealth. These unstable arrangements persisted into the nineteenth century.

Trade and slavery characterized the second Islamic period in Kenya, extending from 1700 to 1880. Slaves were needed throughout the Arabian Peninsula to man Arab armies, to perform manual labor, and to serve as house servants and harem eunuchs. Europeans, particularly the French, also employed slaves in their newly acquired colonial outposts. The slave trade was controlled by Gulf merchants, who arranged orders and supplied dhow transport. Kenya-based Arabs organized expeditions and either led these forays themselves or relied on Swahili middlemen. Onslaughts of slave hunting tore apart indigenous coastal societies and spread enormous suffering as far west as the eastern Congo. Slaving continued throughout the 1700s, to be challenged only in 1807, when the British abolished slavery and initiated the long process of ending the trade.

A key personality in the Indian Ocean antislavery movement was Said bin Sultan, more commonly known as Sayyid Said, who became imam of Oman in 1806. Sayyid Said realized that he required British help to consolidate his rule in Oman and to reclaim Oman’s eastern African territories. He was thus persuaded to accede to the Moresby Treaty of 1822, a European-Zanzibari agreement prohibiting the sale of slaves to Christian powers. Backed by the British, Sayyid Said traveled to Mombasa in 1828, expelled the Mazruis from Fort Jesus in 1836, and soon after moved his capital from Oman to Zanzibar. From there he extended his trading empire from Mogadishu to the Ruvuma, ruling both Oman and coastal eastern Africa until his death in 1856.

During the last twenty years of his reign, Sayyid Said displayed little enthusiasm for the antislavery movement and in fact lacked enforcement power over his acquisitive mainland and island subjects. Slavery continued and in some areas increased. It was not until a suecessor, Said Barghash, took stronger pro-British measures that the trade began significantly to diminish.6 Said imposed a total ban in 1873, but because the measure was still extremely unpopular among traders and coastal merchants, clandestine slaving persisted. Trafficking in human beings provided a powerful incentive for Arab entrepreneurs and their Swahili agents. An equally compelling humanitarian concern for its abolition excited the interest of two other entrepreneurial groups. These introduced even more portentous alien forces, one religious and the other imperial, into eastern Africa.

The European Penetration, 1880–1915

After “discovering” eastern Africa in the early to middle 1800s, Christian missionaries and missionary-explorers became preoccupied with two objectives: to stamp out the slave trade and domestic slavery and, through Protestant and Roman Catholic conversion, to confer a firm sense of Victorian morality on the indigenous societies thus saved. Given competing Islamic beliefs and economic practices along the coast and the potential resistance of myriad inland African societies, both tasks were formidable. Two such proselytizers, Johann Krapf and Yohannes Reb-mann, established Mombasa’s first mission station in 1846, but it was not until Said Barghash’s banning of slavery in 1873 that missionaries felt free to speak out against the practice. Even then, there was widespread opposition; the resident Muslim population resented Christian teachings, and slavery was still a profitable business. General resistance was also encountered up-country until growing numbers of Africans began to associate religious conversion with the acquisition of colonial economic rewards.

Indeed, David Livingstone and those who followed him believed that commerce would pave the way for Christianity and that profit derived from a wage-labor system would put an end to all forms of servitude. From the 1870s on, European travelers and traders, particularly those involved in the Uganda caravans, came under strong moral pressure to pay fully for their porters and to avoid compulsory labor. Missionaries instructed their converts in the mechanical and agricultural arts and committed Kiswahili to the Roman alphabet so that it could serve future economic and administrative purposes as well as their own. In short, missionaries carried the related messages of Western religion, orderly progress, and commercial profit.7 These lessons, especially the latter, were not lost on those who were to feel the full impact of colonial rule.

In contrast to the Portuguese, the second wave of eastern Africa’s European invaders, led by explorers and missionaries, intended to move inland and, eventually, to settle. In the south, Germans occupied what later became Tanganyika Territory (plus present-day Rwanda and Burundi) and ultimately independent Tanzania (including Zanzibar). To the north, Britain claimed Kenya as its East Africa Protectorate in 1895 and in 1920 annexed all but the coastal strip as Kenya Colony. The coast remained under the nominal jurisdiction of Zanzibar, by now itself, like Uganda, a British protectorate.

The motives for this penetration were religious, economic, and political. By 1880, the missionary movement was bringing strong pressure on the British government to commit itself more fully to the antislavery campaign and to protect Victorian clergymen venturing up-country. The economic prospects of the entire region had been dramatically altered with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Kenya was now closer to England, and Mombasa had suddenly become an important strategic port on the British trade route to India and the Far East. European industrialization had produced intense economic and political rivalries, allowing France and Germany to challenge Britain’s technological dominance. In particular, new railroad technology facilitated communication from the sea to the African interior and stimulated the European demand for resources, markets, and the political prestige associated with empire.

For Kenya as for the rest of its African territories, Britain’s initial colonial strategy was to permit commercial interests to take the lead and assume the attached risks. In 1888 a privately financed trading company, the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC), was awarded a royal charter to develop commerce in the protectorate. IBEAC was structured like its British-African counterparts, the Royal Niger Company and the British South African Company, but unlike these enterprises it was not based on new mineral concessions or the prospect of quick agricultural profits. Seemingly without direction, the company drifted into financial straits, and this and the founding of the Uganda Protectorate in 1894 led the British government to assume direct control over Kenya in 1895.

According to a logic that today seems fanciful, British policy focused on Uganda as a key to its strategic interests in Africa. The reasoning was that unless Britain controlled Uganda, the headwaters of the White Nile might be dammed by another European power. This would disrupt the river, bring Egyptian agriculture to its knees, cause peasant uprisings in Egypt and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, threaten the Suez Canal, and prevent British entry to the Red Sea and beyond. India, the Pearl of the Empire, and the Far East trade could become virtually inaccessible. In reality, damming the Nile would have meant transporting heavy equipment to Uganda, 800 kilometers (500 miles) inland, through a territory with no improved roads or bridges, and thereafter building a structure that was technologically far beyond nineteenth-century capabilities. Nevertheless, Britain moved to safeguard its perceived interests and brought Uganda under its “protection.” This action created the need for a supply line to link Uganda with the Indian Ocean, hence the need for an East Africa Protectorate. At first, the Kenyan interior was important not so much in its own right as because it happened to lie between Uganda and the sea and just to the north of suspicious activity in German East Africa.8

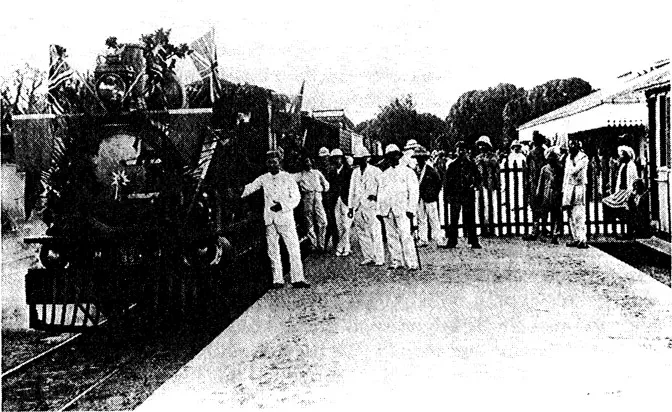

Begun in 1896, the Uganda Railway played a key role in creating the demographic, political, and socioeconomic configurations of modern Kenya. The immediate aims were to extend a line deep into the un-mapped heartland of eastern Africa, to make it pay for itself through exports and by attracting settlers, and to safeguard an important source of the Nile. The ultimate consequences of the Uganda Railway were much more profound and far-reaching.

First train to leave Mombasa for Voi, April 1898 (photo by David Keith Jones/Images of Africa Photobank)

Construction problems were staggering. Little technical knowledge existed about the terrain that would have to be crossed. Because Africans were averse to the grueling work of railway building, more than thirty thousand indentured laborers had to be imported from India. These workers suffered in the sweltering heat, and some fell victim to man-eating lions in what is now Tsavo National Park. As unanticipated problems mounted, the enterprise quickly became a political issue in Britain. Skeptical of arguments defending the line’s commercial potential, detractors dubbed the Uganda Railway the “lunatic line.”9 When the railway was completed, some seven thousand of the “Asian” (Hindu and Muslim Indian) work force elected to stay in Kenya. Mostly cooks, artisans, and suppliers, these immigrants swelled the ranks of an existing minority community that would eventually make a significant commercial impact on Kenya and add complexity to the country’s ethnic and emerging class structures.10

The railway line followed older caravan tracks leading through dry coastal bush country and gradually climbing toward the 2,100-meter (7,000-foot) Rift Valley escarpment, 480 kilometers (300 miles) from Mombasa. At a place called Ngongo Bargas on the escarpment, forest-dwelling Kikuyu and grassland Maasai had long met to resupply and trade with passing caravans. It was near here that the railway built its repair shops and, after 1905, settlers attracted by the area’s temperate climate and clear water established the commercial and administrative capital of Nairobi.11

Arriving at Ngongo Bargas as a young adventurer in 1890, Frederick Lugard lived for a time with the Kikuyu.12 Despite the Kikuyu’s reputation for violence, Lugard reported them peaceful, helpful, and eager to learn European ways. A different impression was left on Francis Hall, who served first as an IBEAC agent and then as a protectorate official. Siding with the Maasai in land disputes with the Kikuyu, Hall pressed farther north into present-day Murang’a District and encountered Kikuyu hostility. He proceeded to “pacify” the area with heavily armed Swahili troops. In 1894 Stuart Wall, central Kenya’s first missionary, walked with his family from Mombasa to Ngongo Bargas and set up a mission station.

Following early contacts such as these, two developments occurred that facilitated the economic opening of central Kenya. First, the British were able to solicit the cooperation of two senior chiefs, Lenana, a Maasai, and Waiyaki, a Kikuyu. Lenana helped create a safe passage through Maasailand, an area that for decades had posed serious dangers to caravans. Although less powerful than the paramount rulers o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Colonial Legacy

- 2 Independence: The Kenyatta Era

- 3 Ecology and Society in Modern Kenya

- 4 Modern Politics: The Moi Era

- 5 Modern Economic Realities

- 6 The International Dimension

- 7 Kenya at the Crossroads of Development

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Acronyms

- About the Book and Authors

- Index