- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Group Performance And Interaction

About this book

This book presents theoretical expositions of the various group topics and descriptions of existing research, emphasizing performance and interaction issues. It discusses some specific groups, of workplace groups, juries, computer-based groups, and other unique groups.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

SociologieChapter One

Introduction and Overview

Groups are all around us. We all belong to groups—be it work groups, family groups, play groups, political groups, and so on. It is our good fortune that the publication of this book coincides with the 100-year anniversary of the beginning of group research. In 1898, Norman Triplett initiated this subject of research with his study of bicycle racers (see Chapter 5), and since that time research on groups has been a growing, dynamic, and exciting area of study. The focus of this volume is on group performance and interaction. Of course, as with any topic as extensive as group performance and interaction, we have by no means exhausted the range of issues that could potentially fit under this umbrella. However, we have tried to focus on some of the major topics and on some exciting new developments that we believe have not received adequate coverage in previous volumes.

Group performance and interaction is an interesting and fundamental area of study, with an unabashedly “social” flavor. Over the years, the specific topics of focal interest to group researchers have waxed and waned. Steiner (1974, 1983, 1986), for instance, has written several interesting analyses of factors related to the activity level in the area of group research. Moreland, Hogg, and Hains (1994) have suggested that an interest in group research is in fact on the increase in recent years, and Sanna and Parks (1997) have pointed out that interest in group research has taken hold within many areas of psychology. Because of this, we would venture to speculate that the study of groups will never become a dormant interest to psychologists and researchers and theorists in other areas. It deals with a whole range of intriguing questions about how people are influenced by the groups to which they belong, or with whom they are interacting, and how these groups in turn might be influenced by their members. What is the experience of being in a group? What types of influences might groups have? What are the influences of groups on decisionmaking and performance? What are the implications of being in groups for applied settings, such as workplaces, juries, or airline cockpits? These are just a few examples of some of the many issues that are represented in Group Performance and Interation. Thus, although the specific topics of focal interest to group researchers may have changed as the years have passed and will likely continue to do so, we believe that the general enthusiasm for group performance and interaction issues will remain constant.

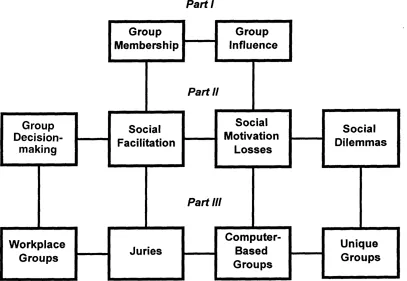

Although undoubtedly there are many other ways in which we could have organized this book, we have chosen to do so in the context of three main sections or parts; these are depicted in Figure 1.1. In Part One, we focus on some basic group processes. These include the experience of group membership (Chapter 2) and group influence (Chapter 3). Group members are often subject to several forces that affect their formation and development, in both natural and experimental settings. Such factors as affinity or similarity, for instance, seem to have an ubiquitous influence on the choice to join and maintain belonging to a group (Simpson & Harris, 1994). This feeling of “closeness” to other human beings appears to be at the heart of our existence. When interacting in groups, people develop a sense of affinity with the group to which they belong, their “ingroup,” and they have a tendency to differentiate this from other, outside groups, or “outgroups” (Brewer, 1979). This differentiation, at least at times, can be an important source of status (Berger, Webster, Ridgeway, & Rosenholtz, 1986) or social identity (Tajfel, 1982; Turner, Oakes, Haslam, & McGarty, 1994). In Chapter 3, we focus on some basic influence processes that may occur when people are part of, or are interacting with, a group. This chapter is divided into two main parts, each dealing with a description of how people can influence, and can be influenced by, other group members. Several models of group influence have been proposed, which focus variously on group members as both sources and targets of influence (e.g., Knowles, 1978; Latane, 1981; Mullen, 1983; Tanford & Penrod, 1984). Each of these models focuses on the influence of the number of present group members, their closeness, and their strength, either individually or in some combination. In the second part of this chapter, we focus on some dual process models of group influence, which attempt to address the relationships between majority and minority influence. In groups, there is a push for consensus, information can be shared and categorized, and so on (e.g., Crano, 1994; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). We have chosen to include these topics at the beginning of our book because these issues are relevant to virtually all aspects of group life and thus are presumed to be operative in behaviors discussed in each of our following chapters.

Part Two represents what is perhaps the real heart of our book. Here we discuss and describe some primary topics of group performance and interaction. We begin with a discussion of the fascinating topic of group decisionmaking (Chapter 4). On the surface, the assumption is often made that groups make better decisions than individuals. In Chapter 4, however, we see that this is not always the case. We discuss issues such as brainstorming in groups (e.g., Diehl & Stroebe, 1987), conflict within groups (e.g., McGrath, 1984), group discussion (Stasser & Titus, 1987), groupthink (Janis, 1982), and many other issues critical to group decisionmaking. An assumption of much of the group decisionmaking literature is that the outcomes of a successful or unsuccessful decision represent a particular type of performance. Building on this notion, in Chapter 5, we begin to examine specific performance issues. The “social facilitation effect,” as it has come to be known, represents an important group phenomenon, as it tests the effects of perhaps the most minimal of social conditions. Social facilitation researchers have tried to assess a contrast between performances when alone versus performances when audiences or coworkers are present. We describe and discuss several intriguing theories on this issue as well as research that has been designed to test performance differences (e.g., Baron, 1986; Cottrell, 1972; Zajonc, 1965).

FIGURE 1.1 Overview of the book

In Chapter 6, we describe social motivation losses. Many investigators had noticed that group members do not always seem to perform up to their individual potential. For example, when people work in groups, they sometimes “loaf” because they believe that others cannot identify or evaluate their individual performances (e.g., Williams, Harkins, & Latane, 1981; Harkins & Jackson, 1985). In short, people “slack off.” However, sometimes people working in groups exhibit motivation losses because they can “free ride” (they believe they can take advantage of others’ efforts) or because they do not want to be a “sucker” (they do not want others to take advantage of their efforts) (e.g., Kerr, 1983). Each of these processes can result in social motivation losses, albeit for different reasons, as we describe. At times, however, far from motivation losses, people are sometimes willing to compensate for others when working in groups (Williams & Karau, 1993).

This notion of what appear to be motivation losses or gains is picked up again in Chapter 7, on social dilemmas. An individual in a social dilemma is faced with a choice between individual self-gain versus the collective good (e.g., Komorita & Parks, 1995). A classic example, is a “resource dilemma.” Suppose you are a fisher and you are faced with a potential shortage of tuna. You make your livelihood catching tuna, and the more fish you catch the more money you make. It may seem rational for you to try to catch all the fish you can. A problem arises, however, if the other fishers try to do the same thing—catch all the fish they can. If this happened, there would soon be no tuna left at all, the fish population could not replenish itself, and no one would have a job catching fish (to say nothing of the loss of a species). Chapter 7 focuses on many variables that influence peoples’ decisions in social dilemmas (e.g., group size, Kerr, 1989; trust, Yamagishi, 1986), a primary interactive context for studying group behaviors.

In Part Three, we discuss some specific groups, many of which are in applied areas. Our final section includes a discussion of workplace groups, juries, computer-based groups, and other unique groups. In our discussion of workplace groups (Chapter 8), we discuss topics such as leadership (e.g., Ayman, Chemers, & Fiedler, 1995), equity (e.g., Adams, 1965), relative deprivation (e.g., Folger, 1986b), and negotiation (e.g., Pruitt & Carnevale, 1993), among others. The types of leaders that we have, as well as our perceptions of how we compare to others, most certainly affects our performances and interactions in the workplace. Juries, of course, are another interesting group. How do juries interact and make decisions? In Chapter 9, we explore some relevant variables. Research suggests that such things as the jury’s preferences for decision rules (e.g., Davis, 1980), deliberation style (e.g., Kaplan & Schersching, 1981), and a number of other variables are critical in this regard. In Chapter 10 we deal with an emerging topic in group performance and interaction—that of computer-based groups. Here we deal with such intriguing topics as feelings of anonymity or “deindividuation” (Diener, 1980), “flaming” (Lea, O’Shea, Fung, & Spears, 1992), and other processes that affect groups when working on computers. In Chapter 11, we focus on a variety of group settings, from military groups to flight crews, to sports groups, to hospital teams. In Part Three, we borrow heavily and refer frequently to material covered in our previous chapters, but we also take the liberty to greatly move beyond these prior chapters by discussing much unique material that is particularly pertinent to the topics at hand.

We provide here an introduction and overview of a diversity of group performance and interaction topics that have not as yet been available within any single volume. Because of this breadth, we believe that our book will be of interest not only to psychologists but also to those with interests in many other areas. We have geared our book to the advanced undergraduate and graduate level. However, our primary objective is to expose readers to the variety of theoretical perspectives proposed by group researchers. In short, this book should be of interest to anyone who wishes to gain a greater understanding of group performance and interaction phenomena.

Part One

Basic Group Processes

Chapter Two

The Experience of Group Membership

We begin our examination of groups by asking some of the most basic questions about groups: How do they form? How do they stay together? What is it like to be a member of a group? For some types of groups, the answers to some of these questions are obvious. For example, there is no mystery as to how a jury is formed. It is done through a careful selection process, the goal being to identify a set of people who are impartial, yet capable of processing the evidence and rendering a legal decision. How does the jury stay together? In fact, jurors have no choice about whether they should continue their membership. Only the presiding judge can decide whether a juror should leave the group, and he or she will remove a juror only under extraordinary circumstances: The juror may be very ill, or the judge may feel that the juror’s impartiality has been compromised by outside forces (e.g., a biased news commentary).

Most groups in our society, however, are not so easily analyzed. It is the rare group indeed for which we can easily answer all three of the questions that we have posed. Note that we did not discuss the final question—what is it like to be a member of a group—in the jury example above. This is because it is not clear exactly what impact serving as a juror has on people. You will see in Chapter 8, devoted exclusively to juries, that we have some ideas about how to answer the question of impact, but there are far too many unanswered questions for us to confidently describe the jury experience in every detail.

In this chapter we discuss some basic ideas regarding group assembly, continuation, and impact. The ideas that we introduce appear in other chapters as well, because they are fundamental features of every group.

Group Formation and Development

Let us start with the most basic group issue: How do groups form and stay together? As we alluded to in our jury example, many groups are purposely formed to accomplish a specific goal. A committee is another good example. We refer to such groups as ad hoc groups. This type of group remains together only as long as it takes to accomplish the goal, and then it disbands. By contrast, a second type of group, which we refer to as a natural group, comes together without outside impetus. A good example of a natural group is a group of friends. Groups of friends arise and evolve over time; they are not carefully constructed to achieve a goal. In the following text, we will see how natural groups form.

Regardless of how the group was assembled, all groups develop sets of behavioral rules. These rules address such things as acceptable behavior within the group, rules of procedure, and roles. The rules may also touch upon issues such as which attitude about a topic is considered appropriate for group members to hold; how group members should present themselves in terms of dress and appearance; and even what constitutes morality. Where do these rules come from? How are they learned and transmitted? We will discuss these questions also.

Finally, we need to understand how groups survive. As with the jury, some groups are prohibited from breaking apart until the goal is accomplished, but even an ad hoc group is not guaranteed of surviving until the goal is met. We will look at what factors determine group survival.

Formation of Natural Groups

How do natural groups develop? The strongest factor is attraction. Quite simply, natural groups will not form if their members are not attracted to one another. (It is important to understand that, to a researcher, the term attraction refers to a general sense of wanting to be with other people. Many people equate attraction with romantic attraction and assume that if two people are attracted to each other, they are romantically linked. When we talk about attraction, we are using the general term.) There are many factors that determine whether people are attracted to one another.

Rewards. We like to associate with people who provide us with rewards (Aronson & Linder, 1965). All else being equal, we are most attracted to groups that, by mere membership in the group, convey upon us social rewards. For example, a particular group might be very prestigious, and to be a member of that group is considered a great honor. We can also get rewards from the other group members, most often in the form of praise and a sense of self-worth. In fact, it has been argued that a major reason that adolescents join gangs is because of the rewards gang membership conveys, rewards that its members cannot receive elsewhere: Being in a gang provides status and prestige (at least in certain communities), money and material goods, and gang members provide support to each other (Burden, Miller, & Boozer, 1996).

When we think about the rewards of group membership, we actually think in terms of a cost/benefit ratio: W...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction and Overview

- Part One Basic Group Processes

- Part Two Group Performance and Interaction

- Part Three Specific Types of Groups

- Appendix: Methodological Issues in Groups Research

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Group Performance And Interaction by Craig D Parks,Lawrence J Sanna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Sociologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.