- 500 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Visualizing Theory is a lavishly illustrated collection of provocative essays, occasional pieces, and dialogues that first appeared in Visual Anthropology Review between 1990 and 1994. It contains contributions from anthropologists, from cultural, literary and film critics and from image makers themselves. Reclaiming visual anthropology as a space for the critical representation of visual culture from the naive realist and exoticist inclinations that have beleaguered practitioners' efforts to date, Visualizing Theory is a major intervention into this growing field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visualizing Theory by Lucien Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

three

Modernity’s Mediations The Scopic and the Haptic

Physiognomic Aspects of Visual Worlds

Michael Taussig

Nature creates similarities. One need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift of seeing resemblances is nothing other than a rudiment of the powerful compulsion in former times to become and behave like something else. Perhaps there is none of his higher functions in which his mimetic faculty does not play a decisive role.

— Walter Benjamin, first paragraph of “On the Mimetic Faculty.” (1934)

PLEASE NOTE THE PITCH MADE FOR THE IMPORTANCE OF THE “MIMETIC FACULTY” IN all of our “higher functions.” For this four-page essay of Benjamin’s is by no means an esoteric aside. All the fundamentals are herein composed; from his theories of language of persons and of things, to his startling ideas concerning history, art in the age of mechanical reproduction and, of course, that infinitely beguiling aspiration, the profane illumination achieved by the dialectical image dislocating chains of concordance with the one hand, reconstellating in accord with a mimetic snap, on the other.

His fascination with mimesis flows from the confluence of three considerations: alterity, primitivism, and the resurgence of mimesis with modernity. Without hesitation Benjamin affirms that the mimetic faculty is the rudiment of a former compulsion of persons to “become and behave like something else.” The ability to mime, and mime well, in other words, is the capacity to Other. Second, this discovery of the importance of the mimetic is itself testimony to an enduring theme of Benjamin’s, the surfacing of “the primitive” within modernity as a direct result of modernity, especially of its everyday-life rhythms of montage and shock alongside the revelation of the optical unconscious made possible by mimetic machinery like the camera and the movies. By definition this notion of a resurfacing of the mimetic rests on the assumption that “once upon a time” mankind was mimetically adept, and in this regard Benjamin refers specifically to mimicry in dance, cosmologies of microcosm and macrocosm, and divination by means of correspondences revealed by the entrails of animals and constellations of stars. Much more could be said of the extensive role of mimesis in the ritual life of ancient and “primitive” societies. Third, Benjamin’s notion regarding the importance of the mimetic faculty in modernity is fully congruent with his orienting sensibility towards the (Euro-American) culture of modernity as a sudden re juxtaposition of the very old with the very new. This is not an appeal to historical continuity. Instead it is modernity that provides the cause, context, means, and needs, for the resurgence—not the continuity—of the mimetic faculty. Discerning the largely unacknowledged influence of children on Benjamin’s theories of vision, Susan Buck-Morss makes this abundantly clear with her suggestion that mass culture in our times both stimulates and is predicated upon mimetic modes of perception in which spontaneity, animation of objects, and a language of the body combining thought with action, sensuousness with intellection, is paramount. She seizes on Benjamin’s observations of the corporeal knowledge of the optical unconscious opened up by the camera and the movies in which, on account of capacities such as enlargement and slow motion, film provides, she says, “a new schooling for our mimetic powers.”1

The Eye as Organ of Tactility: The Optical Unconscious

Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction.

— Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

To get hold of something by means of its likeness. Here is what is crucial in the resurgence of the mimetic faculty, namely the two-layered notion of mimesis that is involved—on the one hand a copying or imitation and, on the other, a palpable, sensuous, connection between the very body of the perceiver and the perceived (which ties in with the way Frazer develops what he takes to be the two great classes of sympathetic magic in The Golden Bough, the magic of contact, on the one hand, and that of imitation, on the other). Elementary physics and physiology might instruct that these two features of copy and contact and are steps in the same process, that a ray of light, for example, moves from the rising sun into the human eye where it makes contact with the retinal rods and cones to form, via the circuits of the central nervous system, a (culturally attuned) copy of the rising sun. On this line of reasoning contact and copy merge with each other to become virtually identical, different moments of the one process of sensing; seeing something or hearing something is to be in contact with that something.

Nevertheless the distinction between copy and contact is no less fundamental, and the nature of their interrelationship remains obscure and fertile ground for wild imagining— once one is jerked out of the complacencies of common sense-habits. Witness the bizarre theory of membranes briefly noted by Frazer in his discussion of the epistemology of sympathetic magic, a theory traced to Greek philosophy no less than to the famous Realist, the novelist Honoré de Balzac, with his explanation of photographs as the result of membranes lifting off the original and being transported through the air to be captured by the lens and photographic plate!2 And who can say we now understand any better? To ponder mimesis is to become sooner or later caught, like the police and the modern State with their fingerprinting devices, in sticky webs of copy and contact, image and bodily involvement of the perceiver in the image, a complexity we too easily elide as non-mysterious with our facile use of terms such as identification, representation, expression, and so forth—terms which simultaneously depend upon and erase all that is powerful and obscure in the network of associations conjured by the notion of the mimetic.

Karl Marx deftly deployed the conundrum of copy and contact with his use of the analogy of light rays and the retina in his discussion of commodity fetishism.3 For him such fetishization resulted from the curious effect of the market on human life and imagination, displacing contact between people onto that between commodities, thereby intensifying to the point of spectrality the commodity as an autonomous entity with a will of its own. “The relation of producers to the sum total of their own labor,” wrote Marx, “is presented to them as a social relation, existing not between themselves, but between the products of their labor.” It is this state of affairs that makes the commodity a mysterious thing “simply because in it the social character of men’s labor appears to them as an objective character stamped upon the product of that labor.” What is here decisive is the displacement of the “social character of men’s labor” into the commodity where it is obliterated from awareness by appearing as an objective character of the commodity itself. The swallowing up of contact we might say, by its copy, is what ensures the animation of the latter, its power to straddle us.

Marx’s optical analogy went like this. When we see something, we see that something as its own self-suspended self out there, not the passage of its diaphanous membranes or impulsions as light waves or howsoever you want to conceptualize “contact” through the air and into the eye where the copy now burns physiognomically, physioelectrically, onto the retina, and as physical impulse darts along neuroptical fibers to be further registered as copy. All this contact of perceiver with perceived is obliterated into the shimmering copy of the thing perceived, aloof unto itself. So with the commodity, mused Marx, a spectral entity out there, lording it over mere mortals who, in fact, singly and collectively in intricate divisions of market orchestrated interpersonal labor-contact and sensuous interaction with the object-world bring aforesaid commodity into being. We need to note also that as the commodity passes through and is held by the exchange-value arc of the market circuit where general equivalence rules the roost, where all particularity and sensuosity is meat-grindered into abstract identity and the homogeneous substance of quantifiable money-value, the commodity conceals in its innermost being not only the mysteries of the socially constructed nature of value and price, but also all its particulate sensuosity—and it is this subtle interaction of sensuous perceptibility and imperceptibility that accounts for the fetish quality, the animism and spiritual glow of commodities, so adroitly channeled by advertising (not to mention the avant-garde) since the late nineteenth century.

As I interpret it (and I must stress the idiosyncratic nature of my reading), not the least arresting aspect of Benjamin’s analysis of modern mimetic machines, particularly with regards to the mimetic powers striven for in the advertising image, is his view that it is precisely the property of such machinery to play with and even restore this erased sense of contact-sensuous particularity animating the fetish. This restorative play transforms what he called “aura” (which I here identify with the fetish of commodities) to create a quite different, secular, sense of the marvelous. This capacity of mimetic machines to pump out contact-sensuosity encased within the spectrality of a commoditized world is nothing less than the discovery of an optical unconscious, opening up new possibilities for exploring reality and providing means for changing culture and society along with those possibilities. Now the work of art blends with scientific work so as to defetishize yet take advantage of marketed reality and thereby achieve “profane illumination,” the single most important shock, the single most effective step, in opening up “the long-sought image sphere” to the bodily impact of “the dialectical image.” An instance of such an illumination in which contact is crucial is in his essay on Surrealism. Here Benjamin finds revolutionary potential in the way that laughter can open up the body, both individual and collective, to the image sphere. What he assumes as operant here is that images, as worked through the surreal, engage not so much with mind as with the embodied mind where “political materialism and physical nature share the inner man, the psyche, the individual.” Body and image have to interpenetrate so that revolutionary tension becomes bodily innervation. Surely this is sympathetic magic in a modernist, Marxist revolutionary key? Surely the theory of profane illumination is geared precisely to the flashing moment of mimetic connection, no less embodied than it is mindful, no less individual than it is social?

The Third Meaning

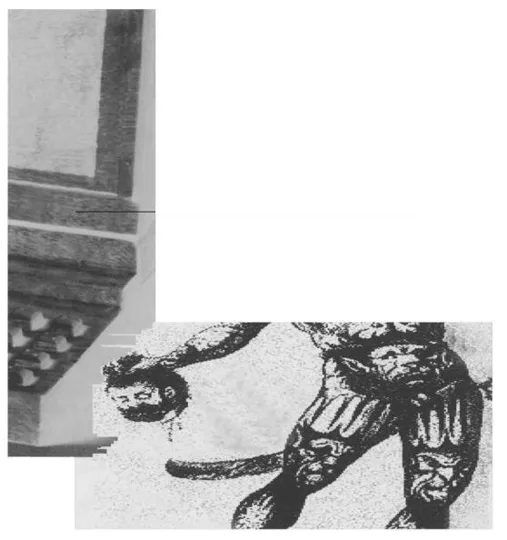

Benjamin’s theses on mimesis are part of a larger argument about the history of representation and what he chose to call “the aura” of works of art and cult objects prior to the invention of mimetic machines such as the camera. These machines, to state the matter simplistically, would create a new sensorium involving a new subject-object relation and therefore a new person. In abolishing the aura of cult objects and artworks, these machines would replace mystique by some sort of object-implicated enterprise, like surgery, for instance, penetrating the body of reality no less than that of the viewer. All this is summed up in his notion of the camera as the machine opening up the optical unconscious, yet before one concludes that this is ebullient Enlightenment faith in a secular world of technological reason, that the clear-sighted eye of the camera will replace the optical illusions of ideology, we can see on further examination that Benjamin’s concept of the optical unconscious is anything but a straightforward displacement of “magic” in favor of “science”—and this in my opinion is precisely because of the two-layered character of mimesis as both (1) copying, and (2) the visceral quality of the percept uniting viewer with the viewed, the two-layered character so aptly captured in Benjamin’s phrase, physiognomic aspects of visual worlds. Noting that the depiction of minute details of structure as in cellular tissue is more native to the camera than the auratic landscape of the soulful portrait of the painter, he goes on to observe in a passage that deserves careful attention that

at the same time photography reveals in this material the physiognomic aspects of visual worlds which dwell in the smallest things, meaningful yet covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams, but which, enlarged and capable of formulation, make the difference between technology and magic visible as a thoroughly historical variable.4

But where do we really end up? With technology or magic—or with something else altogether where science and art coalesce to create a defetishizing/reenchanting modernist magical technology of embodied knowing? For it is a fact that Benjamin stresses again and again that this physiognomy stirring in waking dreams brought to the light of day by the new mimetic techniques bespeaks a newly revealed truth about objects as much as it does about persons into whom it floods as tactile knowing. “It hit the spectator like a bullet, it happened to him, thus acquiring a tactile quality,” Benjamin pointed out with respect to the effect of Dada artworks which he thus considered as promoting a demand for film, “the distracting element of which is also primarily tactile.”5 The unremitting emphasis of the analysis here is not only on shocklike rhythms, but on the unstoppable merging of the object of perception with the body of the perceiver and not just with the mind’s e...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowlegements

- Contents

- One The Ethinographic and the lpsographic

- Two Surrealism Vision, and Cultural Criticism

- three Modernity's Mediations The Scopic and the Haptic

- four Visualizmg Theory: “In Dialogue”