- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

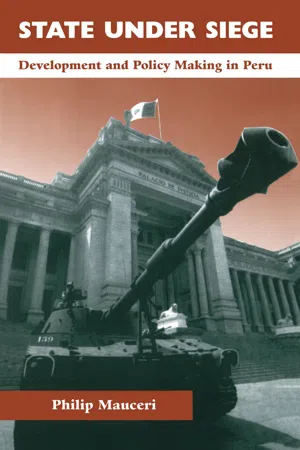

About this book

Using a framework that highlights how societal and international factors have shaped state capacities, Philip Mauceri examines Perus volatile politics in the countrys move from a developmentalist state to neoliberalism. He explores the challenges to state authority during the military regimes reformist experiment, arguing that they were intensified in the 1980s by poor planning and limited policy choices. He then examines how social and international conditions have influenced the Fujimori regimes attempt to retool the state along neoliberal lines. }Using a framework that highlights how societal and international factors have shaped state capacities, Philip Mauceri examines the volatile politics in Peru from the Velasco through the Fujimori regimes as the country has moved from a developmentalist state to neoliberalism.Dr. Mauceri begins by reassessing the reformist experiment of the Peruvian military regime (19681980), arguing that it led to the development of unexpected challenges to state authority, both from new social actors and international financial organizations. During the 1980s, these challenges intensified, made even worse by poor planning and limited policy choices. The author then argues that the attempt by the Fujimori regime, backed by a neoliberal coalition, to retool the state indicates the degree to which state capacities are determined by social and international conditions. Mauceri also gives special attention to the relation between changing state power and social control. Separate chapters on the evolution of a Lima shantytown and the Shining Path examine how changes in state-society relations have had impacts at the grassroots level.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access State Under Siege by Philip Mauceri in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: State Power and Policy Making

The Plaza Dos de Mayo in downtown Lima is usually bustling with street vendors and decrepit buses carrying people to and from Lima’s outlying shantytowns. On a summer January morning in 1988, however, several hundred persons had nearly filled the plaza. They had gathered in front of the headquarters of the Confederación General De Trabajadores del Perú (CGTP), where they shouted anti-government slogans. The CGTP had called this demonstration during what would be the first of five national strikes in 1988 to protest a series of government austerity packages. Yet the events of the day would make this more than just another anti-government protest. As union leaders and United Left politicians denounced the government of President Alan García, a group of some fifty persons marched into the plaza shouting the slogans of the Maoist guerrilla group, Sendero Luminoso: "Viva la Guerra Popular! Viva Presidente Gonzalo!" Within seconds, dynamite exploded behind the crowd and people began to run in terror. Amid the panic and confusion, the intruders quickly moved toward the center of the plaza, firing their pistols into the air. As they did so, armed members of the Communist Party ran out of the CGTP headquarters with their own weapons, surrounding their leaders and firing at the senderistas. While the two groups exchanged fire, the police stood by, apparently unwilling to get involved. The ensuing street battle lasted several minutes until the senderistas dispersed down nearby streets.

For many Peruvians, the events of that day came to symbolize one of the key problems facing their country: violence and the inability of the state to guarantee basic public order. As insurgent forces expanded, the state seemed unable, and at times even unwilling, to confront these groups. State policy makers also seemed unable or unwilling to confront the country’s recurring economic crises. State responses to the economic crisis alternated ineffectually from orthodox to heterodox policies, as the debt burden increased, production declined, and the national income plummeted. Meanwhile, state resources themselves declined precipitously as a result of a dwindling tax base and hemorrhaging public enterprises.

This book will examine the factors contributing to changing state capacities in Peru from the Velasco military regime (1968–1975) through the Fujimori regime of the 1990s. The military regime set into motion the most sweeping set of socioeconomic changes in Peru’s recent history. Through the agrarian reform program, the country’s traditional land-based oligarchy was virtually eliminated. Union and peasant organizations expanded exponentially, and the industrialization fostered by import substitution policies greatly increased the role of the urban working classes. Urbanization, which had been taking place since the 1950s, turned into a flood that overwhelmed the cities.

The changes begun during that regime created new challenges, conflicts, and limitations for a historically limited state. First, these changes gave rise to new radical political movements, both electoral and armed insurgent, that through the 1980s effectively challenged state prerogatives, strained state resources, and exacerbated conflicts and contradictions within the state and between the state and society. Second, the developmentalist economic model adopted in the early 1970s created a series of internal and external vulnerabilities, notably a large debt and an expanding state sector, which led to serious tensions between business elites, government leaders, and international financial organizations. The policies of successive governments, both authoritarian and democratic, appeared only to exacerbate this situation. Policies adopted to deal with the economic crisis and counterinsurgency contributed to a growing polarization in society, increased Peru’s isolation in the international arena, and reduced the resources and capabilities of the state bureaucracy. By the early 1990s a new search for order led to a regime intent on restructuring and strengthening the state apparatus, even if this meant sacrificing democratic norms and institutions.

Before examining these issues, it is important to be clear about what I mean in discussing the state. Following Max Weber, I use the concept of “the state” to indicate that set of administrative and legal institutions that claim “compulsory jurisdiction” over a given territory, maintain “continuous operations,” and monopolize the legitimate use of force. Generally this definition has meant that statehood requires a historical and geographic continuity, a military able to maintain the monopoly on the use of violence, and an administrative apparatus that through legal codes and fiscal and tax policies is able to maintain a compulsory jurisdiction over its territory.1 Although the state as a concept has been criticized as ambiguous and susceptible to multiple, often contradictory, definitions, its persistent use and analytical usefulness argue for the importance of the concept, even at the cost of some conceptual ambiguity.2 The value of the Weberian approach is that it allows the analyst to examine concrete institutions and norms that, despite social and economic transformations over time, have a certain continuity in historical terms.

State Power and Capabilities

The literature on the state that has emerged over the last two decades provides a rich new framework for an analysis of political change. Much of that literature has focused upon state power. How one understands state power clearly depends upon the defining characteristics assigned to the state.3 The Marxist approach has largely focused on the patterns of class alliances that support a particular state apparatus and give it defining characteristics. The characteristics of the state are defined by the demands of a particular economy. The problem of state strength or weakness in the orthodox Marxist perspective is thus a matter of the capacity of a dominant class alliance to impose its will on society through the bureaucratic structure of the state. Neo-Marxists, however, concede that state elites are more than just tools for the ruling class(es), and thus may acquire a “relative autonomy” relative to these classes. Nonetheless, state autonomy is limited by the demands of capital accumulation, which tend to undermine state autonomy in the long run.4 A common critique of the Marxist approach is its difficulty in defining the state in institutional terms, beyond the notion of the state as a mere expression of economic domination. States bring with them historical baggage that is the result of a long history and is linked to cultural and national factors that are not discarded with the passing of a particular economic phase. The institutional arrangements of a state are therefore more than just the expression of a dominant class or economic stage.

Another approach is offered by Joel Migdal, who defines state power in relational terms. For Migdal, state power reflects the capacities of the state to influence and control society, and specifically the capacity to regulate social relationships and extract or use resources in ways the state itself decides.5 In his analysis of Third World state-society relations, Migdal finds that virtually all states are stymied in their attempts to control and regulate complex societies, where social groups ignore or circumvent the dictates of a distant and uncomprehending state bureaucracy. To a large degree, this is the result of the nature of societies in the Third World, which he characterizes as composed of a “melange of social organizations” where groups are heterogenous and mechanisms of social control are numerous and widely distributed. Under these conditions, the state is at a disadvantage in its efforts to control society:

the capacity of states (or incapacity, as the case may be), especially the ability to implement social policies and to mobilize the public, relates to the structure of society. The effectiveness of state leaders who have faced impenetrable barriers to state predominance has stemmed from the nature of the societies they have confronted—from the resistance posed by chiefs, landlords, bosses, rich peasants, clan leaders … through their various social organizations.6

The only “strong” state—that is, a state capable of a high level of social control—which Migdal finds in the Third World is Israel, largely due to its war economy and close-knit religious identity. Even powerful bureaucratic states such as Mexico are seen as unable to regulate social relations effectively. Though Migdal’s analysis is aimed at correcting a trend of seeing strong states virtually everywhere, he appears to err at the other extreme. The litmus test that he sets up is one that few First World, let alone Third World states, can pass. Moreover, although societal groups may adapt to state penetration, Migdal pays scant attention to the ways states adapt to societal resistance. As we shall see in Chapter Five, during the Fujimori period there has been a clear attempt to “retool” the state, improving a variety of capacities weakened over the previous two decades and devising new mechanisms of social control that assure continued dominance. The fact that only one state fits in Migdal’s “strong” state category raises the question as to whether the criteria for what constitutes strong or weak states are excessively rigid. Is the ability to control and reshape society the only way to measure state power, or are there other power relations that need to be examined to evaluate state power?

An alternative to the unidimensional power relation set up by Migdal would be one that emphasizes a series of state capacities besides social control. Rickman suggests a functional approach focusing on the three capacities of the modern state: production, decision making, and intermediation. He argues that this focus “brings together the most important macro level connections of the polity, the society and the economy that cannot be adequately analyzed in isolation from one another."7 Perhaps the most comprehensive argument regarding the need to focus on a multiplicity of power relations in evaluating state power is presented by Skocpol in her analysis of states and revolution. She notes the need to study states “in relation to socioeconomic and sociocultural contexts,” by evaluating state resources and capacities in relation to both national and transnational actors.8 Here we find one of the most important differences with analysts such as Migdal, namely the addition of an international dimension in state capacities. Transnational factors are considered “key contextual variables” in the determination of state capacities. States do not operate in a vacuum but interact with other states within specific international state systems and also within the structures of a world capitalist economy. Those interactions are never precisely the same Skocpol suggests but vary according to the specific world-historical time framework. A clear understanding of state activity and its limits thus requires understanding these contextual variables. This is especially relevant to Third World states that are particularly vulnerable to economic decision making in advanced industrial states and the international financial system. The limitations faced by officials setting economic policy in a context where interest rates are set in New York and Tokyo and where transnational corporations can and often do use their influence with the industrialized governments to bring pressure on recalcitrant policy makers in Lima, Nairobi, or Manila, clearly involves an important power relation for all Third World states.

In analyzing the role of states in social revolutions, Skocpol suggests that the sources of state power lie in the state’s ability to carry out basic administrative and coercive functions.9 This provides us with a realistic way to begin to evaluate state power. But what exactly are those functions? Here Skocpol is less helpful, pointing us only toward the maintenance of internal order, the ability to compete with other states, and the perpetuation of the state apparatus. In part, the lack of specificity is intentional. State capacities are not fixed but depend upon the particular mix of class structure, the economy, and the international context. There are many relevant questions that emerge in evaluating state capacities. How well can a state defend the integrity of its territory against external and internal challenges to its authority? Does a state possess sufficient financial resources to carry out its functions? Do state agencies possess technically capable staff, and is there a high degree of internal unity and cohesion among state elites, such as in the command of the armed forces? Are groups in civil society compelled to follow state policy, or are policies set by the state largely evaded by affected groups?

Skocpol’s approach thus forces the analyst of state power to evaluate a variety of state capabilities, including its own organizational capacities, its influence over society, and its relation with other states. Throughout this study, state power will refer to the state’s ability to carry out its basic coercive and administrative functions in these arenas. The effectiveness of the state’s capabilities is the key determinant of state strength. Strong states are those whose capacities are utilized effectively, while weak states suffer from low levels of efficiency and effectiveness. State strength has little to do with size (such as the number of people working in state agencies), brute force (such as the number of people the police can eliminate), or formal prerogatives that cannot be enforced or that lack legitimacy.

Although this approach offers a comprehensive understanding of state power, it presents a serious research challenge given the number of variables involved. Moreover, state power is not fixed in time. Each power relation may vary as a result of changing circumstances. Events since 1989 in Eastern Europe and the former USSR underscore how quickly these changes may take place, and exactly how difficult it is to evaluate state power. Powerful, supposedly totalitarian states, crumbled quickly. Nonetheless, the processes that altered state capabilities in the “totalitarian” East had been underway for some time, as internal capabilities, influence over society, and power relations in the international arena were all dramatically altered during the 1980s.10 Clearly, there are no set quantitative measures of state power. Since the nature of the variables that determine state power change over time, the analyst is forced to evaluate these multiple factors across world historical time, focusing on continuities and changes in capabilities and contexts.

State Power and Policy Making in Peru

In this book I argue that policies adopted by the Peruvian state from the early 1970s through the late 1980s helped undermine state power. I focus on the interplay between social and economic policies and specific state capabilities. Ironically, two sets of policies emphasized—political mobilization and economic development—were part of the developmental state-building effort. Many of these policies were poorly designed or inadequately implemented. Moreover, state agencies undertook new interventionist policies in the economy and society, even as the effectiveness of their policies were diminished by the international environment and the activities of new social actors. The failures of both developmental and neoliberal policies during the 1970s and 1980s ultimately paved the way for the restructuring of state capabilities during the 1990s.

Throughout this study, policies are evaluated in the three arenas of state power discussed earlier: (1) the organizational arena, (2) the international arena, and (3) the state-society arena. In discussing the impact of policy making on state capabilities in Peru, it is important to emphasize the historical context of this process. The Peruvian state has been a historically weak state. As we shall see below, capabilities and resources have traditionally been minimal in each power arena during most of the country’s history. The developmentalism of the 1960s and 1970s, therefore, represented a majo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: State Power and Policy Making

- PART ONE STATE DEVELOPMENT AND POLICY CHOICES, 1968–1995

- PART TWO STATE POWER AND SOCIAL CONTROL

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Book and Author