![]()

1

Introduction

At approximately 2:00 P.M. on November 3, 2004, John Kerry conceded the 2004 presidential election to President George W. Bush, thus ending a close, often bitterly fought campaign. By all accounts 2004 should have been a high-turnout election. It took place in the context of a controversial war and a controversial issue (gay marriage) that had the potential to mobilize voters on both sides of the issue. Additionally, both Republican and Democratic parties, along with their allied interest groups, waged extensive and intense drives to register as many new voters as possible (“Into the Final Straight” 2004), and they spent more money than ever before on a presidential election (www.opensecrets.org).

A record number of voters cast ballots on Election Day (123,675,639), the highest turnout for a presidential election since 1972, with the exception of 1992. The turnout rate for all individuals of voting age (VAP) was 55.3 percent, a five percentage point increase over 2000. The turnout rate for all citizens, excluding individuals ineligible to vote due to citizenship status or incarceration (VEP), was 60 percent in 2004, an almost six percentage point increase over 2000.1

Nonetheless, the turnout rate was a disappointment when compared with those in nineteen other industrialized democracies, including Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and the Scandinavian nations. These democracies have had an average 72.6 percent turnout in their most recent elections, as contrasted with 60 percent for the United States in 2004.2 Thus American voter turnout was nearly thirteen percentage points lower, even in a highly competitive national election with a great deal at stake. Nor is the higher turnout in recent elections among the other democracies a recent aberration.

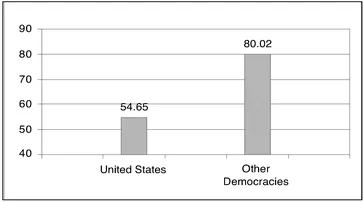

FIG 1.1 Mean Turnout in Established Democracies, 1960–2000

Source: International Institute for Electoral Assistance;

Federal Elections Commission

Figure 1.1 presents the mean turnout rates between 1960 and 2000 for twenty comparable industrialized democracies, including the United States.3 The mean turnout rate for the United States between 1960 and 2000 was 54.65 percent, while in all other industrialized democracies the mean turnout rate over this time period was 80.02 percent. Figure 1.1 demonstrates clearly the substantial turnout difference between the United States and other industrialized democracies.4 It highlights a crucial question about the nature of American democracy: Why is voter turnout in the United States so much lower than in other industrialized democracies, even in situations that seem primed to induce voter participation?

In this book, building on the extant research relating to national-level turnout, I argue that the turnout in U.S. national elections is comparatively low mainly because the electoral, representational, and governmental institutional arrangements in the United States create an environment that constrains rather than facilitates electoral participation. The core of the book will bring to undergraduate students and interested laypersons a systematic understanding of how American institutions have inhibited voter turnout when democratic institutions elsewhere seem more prone to facilitate it. My concern specifically is with why America lags behind other countries in voter turnout, not with the rise or decline in turnout across time among industrialized democracies. Since this issue can be confusing, I shall address it at the beginning of this book.

The Puzzle: Declining Turnout

In 1978 Richard Brody asked why turnout in U.S. elections had steadily declined since 1960, although factors that should facilitate turnout had increased, such as educational levels, and factors that constrain turnout, such as the exclusion of African Americans from the electoral process in the South, had been eliminated. This essay stimulated scholars to explain why American turnout was declining. In the 1960 presidential election, voter turnout was 62.77 percent. From that election forward, however, turnout steadily declined, reaching a low of 50.15 percent in 1988. Following the 55.20 percent turnout in 1992 (the highest since 1972), turnout fell to 49.08 percent in 1996, which was the lowest voter turnout rate since 1924.

In actuality, turnout decline has not been limited to the United States. Most industrialized democracies have experienced declines in the post–World War II era. Among twenty-two industrialized democracies, Franklin (2004) found that the mean turnout trend since 1945 was a 5.5 percentage point decline. Of the twenty-two countries, sixteen experienced declines in turnout since 1945, while only six experienced gains.5 Rather than a symptom of democratic malaise in the United States, turnout decline appears to be a phenomenon occurring in most industrialized democracies (Franklin 2004).

Franklin (2004) provides a compelling explanation for national-level turnout declines (and increases) by arguing that if a cohort of young voters enters the electorate when elections are uncompetitive (i.e., they are low turnout elections), then turnout will decrease in future elections.6 If a cohort (or cohorts) enters the electorate during a period of high competition (and thus high turnout), then turnout should increase in future elections. The logic behind this argument is straightforward. Given that voting is a learned habit, young voters coming of voting age during a low turnout period should continue to abstain throughout their lives and turnout should remain relatively low. If young voters come of age during a high turnout period, then they should continue to vote throughout their lives and turnout should remain high. Franklin’s argument is based on two key factors. The first is that young individuals are socialized into modes of behavior. What happens to young people in their formative years impacts their attitudes and behaviors throughout their lives.

Franklin identifies the lowering of the voting age in many democracies to eighteen during the late 1960s and early 1970s as key to continuing turnout decline. He argues that these new eighteen-year-old potential voters were more susceptible to the electoral environment than their twenty-one-year-old counterparts. Each cohort of eighteen-year-olds that came into the electorate added a larger number of citizens with a low probability of voting.

The second factor (and strongly related to the first) is the “character of elections.” Competitive elections, with strong, cohesive parties that present clear choices to voters, tend to have high turnout because citizen interest is heightened by the increased politicization of the environment. Franklin argues that at the same time countries were lowering the voting age, the character of elections changed in that the competitiveness of elections declined, and thus elections lost some of their mobilizing potential. Given that eighteen- to twenty-year-old potential voters are very susceptible to the electoral environment, their first experience in a low turnout election “socializes” them that elections are uncompetitive and uninteresting and consequently not very important. Each cohort of young people that comes into the electorate during a nonstimulating election period leaves a “footprint” in the electorate: as they age they remain nonvoters. Given the decline in competitive elections over the past couple of decades, many cohorts have entered the electorate in nonstimulating elections and thus turnout has continued to decline.

The other side of this argument is that if new cohorts of voters enter the electorate during a period of competitive elections, then these new cohorts leave a footprint of voters in the electorate and turnout should increase in future elections. National elections in the United States since 2000 have been very competitive and thus it is possible that the cohorts entering the electorate during this period will create a footprint of voting in the electorate and turnout will increase in future elections.

This argument appears to work well in the United States. The voting age was lowered to eighteen in 1971 by the Twenty-Sixth Amendment. This occurred as levels of competition in congressional elections declined (See Fiorina 1989; Mayhew 1974). Each cohort of eighteen- to twenty-year-olds that entered the electorate experienced low turnout elections, and thus a large proportion of each cohort refrained from voting. Across the 1970s and 1980s successive cohorts were socialized to not vote and turnout declined. Franklin also highlights the role played by the separation of powers system. Because policymaking power is fragmented between the executive and legislative branches, the government is less responsive to the demands of the electorate. Additionally the system reduces citizens’ ability to assess governmental performance and accountability is therefore reduced. Turnout is lower, then, because citizens believe that elections have little connection to policy outcomes.

When control of the legislative and executive branches is divided between the two major parties, the effects of the separation of powers are exacerbated by the conflict between the two parties. Divided government has been the norm in American politics in the post–World War II era. Since 1952 there have been only eighteen years of unified control of government, and since 1972 there have been only eight years of unified control. Given the predominance of divided government, each cohort since the passage of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment entered in an era in which the separation of powers sent voters the message that elections were not linked to policy outcomes and thus they were socialized further to not vote. Younger voters, declining competition in elections, and divided government have played a key role in the turnout decline in the United States.

What, then, are the reasons behind lagging turnout in the United States, compared with other industrialized nations? Turnout in the United States was lower before the decline set in. In 1960, the last election before the decline began, turnout in the presidential election was 62.8 percent. In the other nineteen industrialized democracies referred to in this text the mean turnout rate for elections held in 1960 was 80.7 percent.7 Although the decline in the United States appears to have widened the gap between it and other countries, the difference in 1960 illustrates the need to search for explanations to the low turnout in U.S. elections. Franklin’s argument concerning the competitiveness of elections and the role of divided government in turnout highlights the role of institutions in shaping turnout. Using the work of Franklin (2004), Powell (1986), and Jackman (1987), the analysis in this book explores the impact of American electoral and governmental institutions on turnout.

The Turnout Puzzle

Why voting turnout is consistently lower in the United States than in comparable industrialized democracies is a pressing issue for several reasons. First, participation is the heart of democracy, and America prides itself as a birthplace of democracy and the leading proponent of the spread of democracy around the world. Why then are Americans laggard in going to the polls in their own democracy? Second, Americans’ poor participation has a decided bias to it, with the poor, the less educated, and the young less likely to participate than the wealthy, the better educated, and the older. What factors help generate this participation gap? Third, while some have argued that governance is most effective when only the most engaged and informed citizens participate in the political process, the structures of government in the United States are based in part on the belief that widespread participation should be limited to prevent tyranny imposed by an uninformed majority. There is another side to this debate, however. Electoral participation is a matter of voice, of having a true say in the choosing of governmental leaders who craft policy that may have a dramatic impact on people’s lives. Widespread participation creates greater democratic legitimacy because all groups in society have a say in choosing elected officials. Finally, citizen engagement in politics—or lack of it— is often taken as an index to the health of a democracy and public support for it. Are citizens turning out to vote at lower rates in the United States because of deep problems they have with their government—or for more mundane reasons?

In this book I argue that the primary explanation for the lower voter turnout in the United States lies with the nation’s institutional arrangements: American electoral and governmental institutions increase the costs associated with voting, making it far more difficult than it is elsewhere. Consequently a large proportion of the eligible population refrains from voting, particularly those who are most likely to be disengaged from politics, such as the young and those of lower socioeconomic status. Although turnout may rise and fall for a variety of reasons, it is consistently lower in the United States because of institutional reasons. By and large, this lower turnout does not indicate greater citizen unhappiness with the government, as compared with citizens elsewhere; rather, it flows from the complex nature of the political institutions that constitute American democracy. This factor must be considered in evaluations of American democracy, including the tendency to undermine participation among the underclass.

While there are several institutional factors in the United States that complicate national turnout rates, the analysis in this book will focus on the three most consequential ones: (1) registration laws, (2) single-member district, winner-take-all elections, and (3) the separation of powers system. This institutionalist argument is developed in the following seven chapters. Chapter 2 presents the range of theoretical explanations for turnout, including the socioeconomic model, the cultural explanation, and the calculus of voting. It concludes by arguing that an institutional perspective on turnout is the most comprehensive explanation for the turnout differences between the United States and other established democracies.

Chapter 3 explores the impact of registration laws on turnout in the United States. By forcing citizens to take the initiative to vote and setting the time for registration, they increase the costs of registration and thus filter out all but those most likely to vote. Chapter 4 places the U.S. electoral system in context by discussing the various electoral systems used in democracies around the world. Chapters 5–6 examine the impact of single-member district, winner-take-all elections on turnout in the United States. Chapter 7 examines the impact of the separation of powers system on turnout. Chapter 8 concludes by examining the various methods that have a reasonable chance of leading to higher levels of turnout in the United States. These include moving to the proportional allocation of electoral votes in presidential elections, implementing Election Day registration at the national level, moving Election Day to the weekend, implementing early and mail-in voting on a national basis, and instituting public financing of congressional campaigns.