- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The aim of this book is to expand the subject and matter of architecture, and to explore their interdependence. There are now many architectures. This book acknowledges architecture far beyond the familiar boundaries of the discipline and reassesses the object at its centre: the building. Architectural matter is not always physical or building fabric. It is whatever architecture is made of, whether words, bricks, blood cells, sounds or pixels. The fifteen chapters are divided into three sections - on buildings, spaces and bodies - which each deal with a particular understanding of architecture and architectural matter.

The richness and diversity of subjects and materials discussed in this book locates architecture firmly in the world as a whole, not just the domain of architects. In stating that architecture is far more than the work of architects, this book aims not to deny the importance of architects in the production of architecture but to see their role in more balanced terms and to acknowledge other architectural producers. Architecture can, for example, be found in the incisions of a surgeon, the instructions of a choreographer or the movements of a user. Architecture can be made of anything and by anyone.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Architecture by Jonathan Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

building

matter

the future is hairy

‘GOD LIES IN THE DETAILS’

History is not sure that he said this but posterity has ascribed these words to Mies van der Rohe.1 They have become a bead on the architectural rosary. Oft repeated, oft unthought, until they assume an inviolate status for the architectural supplicant. We need to believe the words were said by someone of his stature – otherwise we might playfully misread them as God telling lies: ‘God fibs in the details.’ But we cannot. They issue from Mies – fine, upstanding, well-dressed Mies – and as such transcend any mockery. The act of detailing has thus become a credo overseen by higher values. Architects claim this act as an integral part of their identity, a specific area of expertise, a demonstration of professional control that excludes the amateur. Detailing is one way in which architecture elevates itself above mere building (‘architecture is not building’ being another rosary bead). Builders simply do things as they know best through tried and tested methods, a kind of industrialised vernacular. Architects on the other hand use their expertise in detailing to refine complex conjunctions through the application of technical and aesthetic judgement. Detailing is difficult – an act of penitence that requires learning in order to reach the higher, spiritual plane of the discipline. Starting with the novice, levels of expertise are defined and initiated, each with increasing degrees of mastery.

This discipline of detailing sets architecture apart as a technocracy. Mies, and he really did say this, held ‘that technology was a world unto itself’.2 The architect/technocrat was divided from the world of the great unwashed – the surveyors, the public, the philistine. The architect’s detailed designs are buildable only with specialised craftsmanship and expert labour. To be fully appreciated the final products of this process require a certain aesthetic and technical sensibility, an initiation into the faith. A world set apart, architecture becomes an autonomous discipline defined in part by an adherence to certain principles of detailing.

Is this an overstatement? We believe not. Mies has another aphorism: ‘Architecture begins when two bricks are carefully put together.’ As Beatriz Colomina pithily notes, this is ‘just about the dumbest definition of architecture that I have heard’.3 But it is another maxim passed down through architectural culture, a signal of our removal into a technically defined world. Specifications, legislation, contracts, performance standards and Agrément Certificates – the list goes on – provide institutional policing of the territory. Individual architects cannot expect to cover the whole territory, because the demands set by technical standards are challenging. They do indeed require application and devotion. Added to this, signs of progress must be demonstrated – architecture cannot be seen to stand still – and this demands technical development. Detailing thus becomes an unforgiving treadmill of refinement and improvement, each conjunction judged in relation to its previous manifestation. Small wonder then that the territory is carved up and market niches are contested. Materials are classified (brick, glass, steel, concrete, wood, render) and methods of assembly are defined (hi-tech, eco-tech, lite-tech). Combine one or two from the first group with one of the latter and you have established an area of expertise. As in any language, only certain permutations are permissible, since transgression of categories affronts the rectitude and ordering of architecture.

TRANSGRESSION

The building was still rumbling, half-designed, around our heads when the call came. It was Interbuild, the largest trade show for building materials in the United Kingdom. They wanted us to build a section of our house on the main exhibition stand, in a display called ‘Façades of the Future’. We were both flattered and gently amused at the idea of sneaking in a straw wall as an example of a pioneering future. A hairy Trojan horse. But we wavered. We had not even designed (or detailed) the wall yet, and the exhibition was to open in five weeks’ time. What swayed us was the promise that our exhibit was to be placed next to a section of the Lords Media Centre by Future Systems, described to us as 7m long and shiny. The temptation of juxtaposing our hairy agricultural wall with the smoothness of their nautically inspired technology was too much to resist – the more so since each of us was somehow associated with the sustainable pie. Future Systems’ ecological claim to a slice was based on the weird logic that aluminium (the building’s principal material) was recyclable. Forget the oilfields of energy required to convert bauxite into aluminium, just be consoled by the fact that in order to fulfil this logic the Media Centre will one day be melted down into billions of Coke cans.

Five weeks later we arrive, three amateurs (two of them women) in a self-drive van at a hall full of trucks and big, skilled men. We have three days to erect a wall using a method never previously used, a wall that will be seen by over 100,000 people. The lack of any technological precedent is scary (we have to research everything from scratch and improvise where necessary), but also consoling since there is nothing to judge it against, our method is neither right nor wrong, it is just there. But this does not stop endless big-bellied men coming over, curious and judgemental, waiting to see something they can shake their heads about in the time-honoured construction industry tradition (‘you’re doing it wrong, mate’), allied with conspiratorial winks to feremy (‘lucky bastard, all those women around, mate’) before turning away to reveal the sartorial cliche of the builder (‘seen the crack in your arse, mate?’). Ours was the final laugh when three days later our wall went up on time and according to plan, defeating their scepticism (‘so who’s sophisticated now, mate?’). Our only real disappointment is that when the promised 7m of the Lords Media Centre arrived it had shrunk to a sample 1m square. Something about a ‘problem with production’. Well, we thought (borrowingfrom the automotive industry), ‘Size matters’.4

The exhibit is consciously polemic, and through this becomes a signal for the forthcoming building. We have added a twist to our detailing. We suspect we have been called in as the token eco-people: straw = hairy = handholding = female = amateur = crude = non-rational. A convenient conflation to salve the collective conscience while others get on with the serious stuff. Our twist is to wrap the straw in a transparent polycarbonate screen sourced from an Italian DIY catalogue, so that the straw is exposed to view. It is a transgression of material and technical classifications. Slick meets hairy. The eco-people are offended by the polycarbonate (plastics are not wholesome). The technocrats are confused by the natural stuff. That is two targets in one wall.

SERIOUS STUFF

The technocracy induced by the focus on the detail does not lead to the complete autonomy of architecture. Remember what initiated it: ‘God lies in the details.’ In the Miesian canon, detailing possessed a quasi-spiritual status; attached to it was an associated morality which equated honesty and transparency in visual expression (and in particular the detail) with truth and order in society. As Ignacio Sola Morales notes: The Miesian project in architecture is inscribed within a wider ethical project in which the architect’s contribution to society is made precisely by means of the transparency, economy and obviousness of his architectonic proposal. This is the contribution of truth, of honesty. That is Mies’ message.’5 For Mies this was undoubtedly deeply felt; his philosophical and theological connections to such guides as the Catholic moralist Romano Guardini are well documented.6

Fifty years later the project to provide society’s salvation through recourse to architectural honesty, truth, economy of means and precise tectonics appears deeply flawed and delusional. It might even seem funny if it were not, even now, revered with such intensity. But we are not allowed to laugh at the hopelessness of salvation through good detailing. This is serious stuff, a moral project that still holds certain sections of the architectural community in thrall. David Spaeth, a self-confessed disciple of Mies, states: ‘Because Mies is so personally exacting, his work so uncompromising, he continues to be the architectural conscience of the age. This alone makes him worthy of our continued attention.’7 The word conscience is telling. It is as if architects are in a state of potential truancy, in permanent danger of straying. In our secular age, we redeem our guilt through penitence to the rectitude of detail and tectonics. These days it is not so much God that lies in the details but Guilt. Residual guilt that the redemptive claims of modernism have never been fulfilled, that the sins of society cannot be solved by architecture alone. Not wishing to confront this failure head on, the profession retreats to the higher ground of truth and honesty in construction, one of the few challenges the architect can control. Disciplined making has become a security blanket against the realities, disruption and disorder of everyday life. But it is a blanket that can, with a little thought, be unpicked, taking apart the unsustainable interweaving of the weft of morality with the warp of technology.

FUN

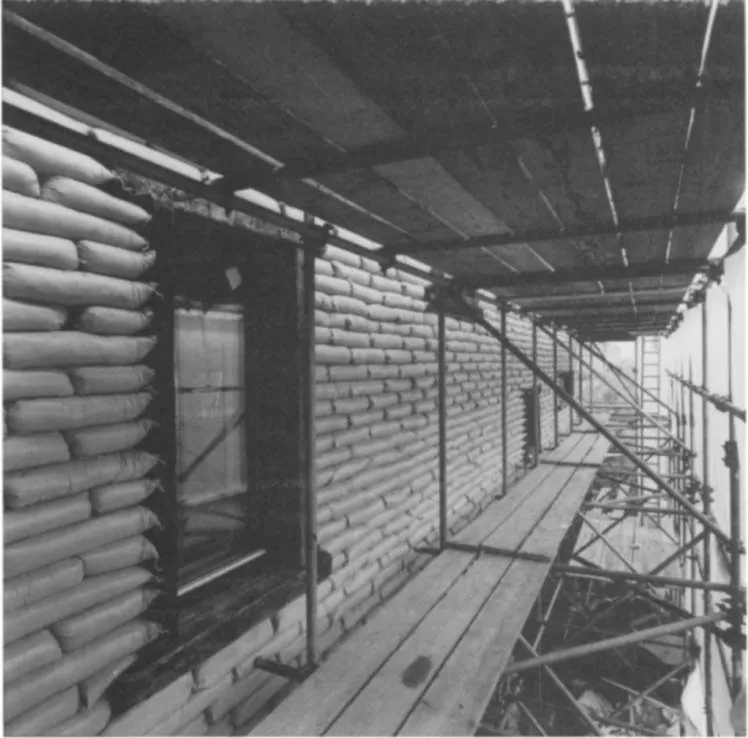

We are building a wall, the one next to the railway line, the one made out of sandbags. This technology has not been tested in London since the Blitz. We have been enthralled by an image of the Kardomah Coffee house in 1941, its full length plate glass windows shielded from German bombs by a wall of sandbags, with refined Londoners attempting to maintain a semblance of coffee-morning normality behind a crude architecture. Sixty years later memories have faded and appropriate skills have been lost, We are now having trouble detailing the windows; framing them in zinc or standard pieces of timber feels too precious. Lying around the site (once a forge for the neighbouring railway) are some old pitch-pine sleepers. In a moment of vernacular inspiration Sarah realises they will wake perfect window surrounds and, together with the builders, sorts out a way of making them work. In their making of the building, the builders have suspended their initial disbelief in the project, and have claimed the various unknown technologies as their own; construction pioneers.

Professor Gage visits us. He looks up at the sleepers. ‘It looks like you are having fun here.’ At first we are dismissive. Building one’s own house is a notorious graveyard of relationships; it is hardly the definition of fun. Then we ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Subject/Matter

- Section 1: Building Matter

- Section 2: Spatial Matter

- Section 3: Body Matter

- Index