- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Citizen Participation In Resource Allocation

About this book

Not all citizens seek to extract a free lunch from government by demanding more services at the same time that they eschew taxes. It is possible to gather the insights of an representative and informed citizenry in sophisticated and reliable form. Citizen Participation in Resource Allocation explores the means to obtaining informed insight from ci

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Citizen Participation In Resource Allocation by William Simonsen,Mark Robbins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Theoretical and Historical Context of Public Participation

Before considering the host of contemporary techniques that governments are using to bring citizen participation into their decision-making processes, we pause to consider how we have arrived at our present understanding of citizen involvement processes. In the earliest days of the republic, the notion of a randomly selected sample of citizen judgments on budgetary dilemmas was nonsensical. Local decisions were citizen decisions by definition when town meetings were the dominant form of local government. The definition of a citizen, and of representation, was relatively narrow. A series of developments in U.S. history, including the swift and dramatic increase in the size of the states (in population and land area) and the government (number of governments, employees, and responsibilities) interacted to produce a unique relationship between the citizen and the decision maker. In this chapter, we consider the ways in which citizen participation has developed in the United States, how the citizen has been regarded in the developing scholarship of public administration (much of which reveals a gap between administration and citizen considerations), and some of the most common responses that governments have developed to fill this “citizen gap.”

Mary Kweit and Robert Kweit (1981) describe three crises of participation in the United States corresponding roughly with the period of western expansion, the attack on the political machines at the end of the nineteenth century, and the social crises of the 1960s. Participation in its contemporary manifestation is traced to this last period.

Kweit and Kweit (1981) describe this understanding of participation as individualist—as opposed to collectivist—in its understanding of the public interest.1 Individualists argue that legitimate decision making must represent an aggregation of the demands of individuals. Collectivists, such as James Madison, argued that such a summation of and accession to citizen concerns would represent a preemption of the public will. Theodore Lowi (1969) argues that (individualist-motivated) interest group liberalism “deranged” expectations of democratic institutions by applying notions of popular decision making to administration.

Although collectivists trust administrators to be stewards of a public will quite separate from public opinion, individualists believe that it is the combined involvement of the citizenry that must prevail in preserving the public trust. Emmette Redford (1969) argues that a government acting without the universal participation of its citizenry lacks democratic morality. He writes in response to the revelation that a unitary and centralized elite no longer prevails in government decision making. In such a decentralized climate, a coalition of like interests is a legitimate expression of democratic will. But factors other than the fragmentation of power contributed to the predominance of the individualistic ideal of citizen participation.

The civil rights movement in the United States revealed to many citizens the degree to which basic rights were being disregarded. It also brought two issues forward in our collective consciousness. One lesson was that groups of citizens joining together could openly resist, and ultimately prevail against, a government that was refusing to act justly. The other was the corollary revelation that citizens could no longer assume that governments would act morally, or even legally. Although this is a now a standard assumption, it marked a dramatic shift in trust from even a few years earlier. By the 1970s, citizens had witnessed the protracted suffering and loss of American and Vietnamese lives in a war that their government perpetuated without popular consensus. With Watergate and the near impeachment of President Nixon, citizens were exposed to an equally grim side of their government, one where its leaders conspired to commit and cover up felonies.

Frederick Mosher (1974), writing on behalf of a panel of the National Academy of Public Administration, notes that most of the participants in the Watergate scandal had no prior history of illegal acts, and he suggests that the political and administrative systems may themselves have contributed to those events. He argues the possibility that such events were less an aberration than a culmination of abuses based on a centralization of power, the roots of which he traces back as far as the Bronlow Committee of 1937. Vincent Ostrom (1989) characterizes the Watergate crisis as the manifestation of a concomitant increase in the centralized power of the executive and a decline in constitutional government. Regardless of the source of the corruption, the Watergate period appears to have precipitated an erosion in the already-dwindling public confidence in the federal government. This is most dramatically evident in the decrease in those responding that they trust their federal government to do what is right always or most of the time from 65% in 1966 to 33% in 1976.2 Those no longer trusting government to do what is right must either suffer its decisions or cause it to act otherwise.

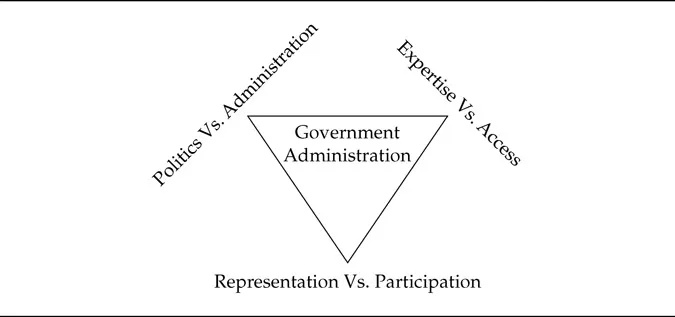

We believe that the circumstances under which citizens have participated in government have played out in the context of certain recurring tensions inherent in the (U.S.) democratic system. The history and intellectual tradition from which this debate has proceeded are best described through three sets of these tensions: representation versus participation, politics versus administration, and bureaucratic expertise versus citizen access. These tensions frame the theater in which government is administered (see Figure 1.1). They are of critical importance as they trade off against one another and frame the ways in which notions of participation have evolved. Questions of governance and the legitimacy of government administration have not always been framed in terms of participation. In this chapter, we use these tensions to examine participation from the perspective of government administration in the United States across time. Understanding the tensions and the developments and character of the periods from which the tensions evolved informs us as we consider the nature of the contemporary call for citizen participation. We believe that these tensions also illuminate a citizen gap whereby distinct citizen interests fail to be incorporated in government. After reviewing these tensions and their historical antecedents, we turn our attention to some of the familiar forms of participation that have evolved.

Figure 1.1 Tensions

From the perspective of state and local government administration, citizen participation connotes extraordinary involvement processes that occur outside of the business of everyday governance. Citizen participation was not always a supplemental or compensatory notion. In fact, Kweit and Kweit (1981) argue that the efforts of citizens defined government itself up until the ratification of the Constitution.

In Europe, the governments existed and citizens were born into an established political order. In the United States, however, with few exceptions, communities existed before their governments, and the people were required by necessity to participate in constructing their own government structures and the laws that would be enforced.

Absent a centralized authority for decision making, and largely preferring none, citizens, through their collective efforts and resources, agreed on the rules by which society would operate and the goods that would be publicly provided. These factors helped to set the stage for some of the ongoing struggles of participation. A series of constitutional and legislative efforts, coupled with growth in the size and scope of government administration, have removed citizens from what had been (until the time of the Constitution) a very direct control of government. Efforts in these domains (local, legislative, constitutional) have attempted to return some of this control.

Representation Versus Participation

The founders of the United States dealt with the immediate concern shared by many: how to create a government that would ensure the sovereignty of a nation while at the same time guaranteeing that this government would not oppress its citizens. The method selected was a process that involved citizens indirectly, through the election of representatives.

James Madison believed that representative government created a dependent, and therefore sympathetic, reliance on the public (Madison, in The Federalist, 52, Hamilton, Madison, and Jay, 1982). Even Thomas Jefferson (1984), although believing in the regular evolution, even revolution, of government by the people, was uncomfortable with the notion of the direct election of representatives. Legislating for the entire union required talents and skills that might not be found in those popularly elected. The outcome was that citizens would elect national and state representatives, state legislatures would select senators, and electors were to pick presidents.

By establishing an executive branch, the Constitution created a new governmental relationship: that between the citizen and the administrator. Early views about the executive office, whether in favor of absolute term limitation (Jefferson) or perpetually renewable tenure (Hamilton), turned on the impact on the citizenry and the ability to preserve citizens’ influence in government affairs. Once the government was established, Hamilton believed its administration should be highly professional and insulated from the citizenry.

Leonard White (1948) describes the ensuing debate over the structure of government as one between Hamilton’s federalists and Jefferson’s republicans. The federalists saw strong executively controlled administrative functions as essential to the development of a strong economy. The republicans argued that the power of government action to enter into the daily affairs of citizens should be exercised locally, where those affected would have the most control.

Hamilton and his contemporaries could not have imagined the size and scope that administration would assume even a few generations later. Citizens may have been content with representation alone in a government of local scope and discrete federal duties. Along with the creation of large bureaucracies came the realization that governmental actors who are not elected have the ability to make decisions that could change people’s lives.

By the time of the Jacksonians, the federal government had become relatively large and centralized. Citizens were moving west to take advantage of available land and resources, and they found themselves in need of the collective services that a distant government could not easily provide. To understand these circumstances, do not visualize the “Wild West” of American film but rather a junior high school class with a substitute teacher. The idea of a distant sovereign (be it a central government or a school principal) was inadequate to provide the structure to accomplish the work that needed to be done.

The Westerners found themselves in need of political structure and created governments where they were needed. The struggle for the removal of obstacles to voting and office holding that ensued has been described as the first participation crisis in U.S. history (Kweit and Kweit, 1981, p. 17). Broadened suffrage rights and the development of the party system created opportunities for greater control and input for the citizenry. President Jackson, himself a Westerner, eliminated the privilege component of appointment to the bureaucracy and established party loyalty as the sole criterion for such jobs. The citizens at large were then represented by the participation of their peers in the bureaucracy.

Participatory or democratic crises, whether resulting from economic catastrophe or political scandal, have boiled this soup from the same set of bones: Is citizen participation through representation and administration alone adequate to ensure the pursuit of the public good? In Public Administration and the Public Interest, Pendelton Herring (1936) argues that neither the administrators nor the citizens and others with competing demands for government can declare themselves sole proprietors of the public interest. They will either substitute their own judgment for that of the people or assert their personal interests. Herring relies on the open scrutiny of administration and the wisdom of administrators to identify and secure the public good. There is no notion of direct participation here, simply the idea that administration becomes representative through vigilance and stewardship in the absence of direct electoral accountability.

Questions about the ability of elected officials to secure the public good led to the reforms of the early twentieth century. Particularly dramatic in terms of the ability of citizens to have increased input in public decisions were the establishment of the ballot initiative, referendum, and recall.3

States allowing initiatives require a certain number or proportion of citizens to sign a petition that places statutory or constitutional changes on the ballot. States with referenda have a provision whereby existing statutes or constitutional provisions are placed on the ballot for voter approval. This may occur through citizen petition or by referral from the legislature. States with recall provisions set a threshold for petition signatures that triggers a vote on the removal of an elected official. It should be noted that none of these provisions are substitutes for a choice by popular vote (election), but rather increase the frequency of such opportunities.

Clearly, such methods of “direct” democracy ensure increased citizen participation in government decision making. The claim that citizens get what they expect from the resulting elections is more troublesome. Thomas Cronin (1989) contends that the evidence from California’s (1978) Proposition 13 and Massachusetts’s (1980) Proposition 2Vi reveal that “voters knew what they wanted to do, and subsequent studies suggest that these tax cuts did not hamper economic development or severely impair city services” (p. 87). These same arguments are harder to make in more contemporary ballot measures such as Oregon’s (1990) Measure 5 and (1997) Measure 50, the impacts of which were complex and very difficult to judge in advance. Furthermore, the use of professional signature gatherers and other commercial petition-generating methodologies have blurred the line between citizen and commercial interests to such a degree that it is unclear whether the benefits of such measures accrue in any manner that correlates with the proportion of votes cast.

Cronin (1989) argues that these provisions, although generally used responsibly by citizens, have failed to go far enough to secure citizen input in federal decision making. He reviews the arguments for and against the establishment of a national referendum to create binding federal law.4’5

Such provisions at the state level already reach ridiculous proportions and are easily subverted by the rapidly burgeoning signature solicitation industry that was partially responsible for the inclusion of a record twenty-three ballot measures in the Oregon elections of November 1996. Opponents of these reforms argue with the founders of the Constitution that there is a difference between public opinion and the public interest. Voting for representatives, these opponents believe, is adequate input, particularly where citizens may have neither time, talent, nor inclination to come to informed judgments.

Thus, since before the Constitution, the degree to which citizens are to be spoken for, or looked after, by government leaders, has been an unresolved tension. Attempts to “reinfuse” the democratic process with greater degrees of citizen input or control are by no means the result of a consensual understanding of the theoretical traditions of the nation. Instead, such innovations represent one understanding on a continuum between two points.

Politics Versus Administration

Citizen participation occurs in the middle of the tension between politics and administration. If politics is completely separate from administration, and administration implies neutral expertise, then the legitimate role of citizens might normatively be confined to the political process. If some blurring of this distinction is conceded, this role can be more broadly construed.

When Woodrow Wilson (1887) wrote about the administration of a constitutional government, he discarded the prevaili...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Theoretical and Historical Context of Public Participation

- 2 Contemporary Techniques for Citizen Involvement

- 3 How Do Citizens Balance the Budget?

- 4 How Fiscal Information and Service Use Influence Citizen Preferences

- 5 Conclusions: Lessons for Governments

- Appendices

- References

- Index