eBook - ePub

Automotive Innovation

The Science and Engineering behind Cutting-Edge Automotive Technology

- 309 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Automotive Innovation

The Science and Engineering behind Cutting-Edge Automotive Technology

About this book

Automotive Innovation: The Science and Engineering behind Cutting-Edge Automotive Technology provides a survey of innovative automotive technologies in the auto industry. Automobiles are rapidly changing, and this text explores these trends. IC engines, transmissions, and chassis are being improved, and there are advances in digital control, manufacturing, and materials. New vehicles demonstrate improved performance, safety and efficiency factors; electric vehicles represent a green energy alternative, while sensor technologies and computer processors redefine the nature of driving. The text explores these changes, the engineering and science behind them, and directions for the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Automotive Innovation by Patrick Hossay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Bringing the Fire

It makes sense to start our exploration of automotive innovation with what has been the heart of the automobile for more than a century: the internal combustion engine. And it makes sense to start a look at the internal combustion engine with the heart of the process: combustion. The very idea of combustion is usually taken for granted, as a notion that is self-explanatory. We all know what combustion is, it’s when something explodes or burns, right? But, thankfully, that’s not exactly what’s taking place in your engine. We’re going to need a more precise understanding of exactly what and how something is burned in an engine before we can understand the complete workings of internal combustion.

So, what exactly is combustion? Put in general terms, it’s a chemical reaction that converts organic material to carbon dioxide while releasing heat energy. The process is called rapid oxidation because it’s defined by a fast reaction with oxygen. So, at the most basic level, a chemist would write down a combustion reaction like this:

Very simply, this means organic materials made of carbon (C), like wood or paper or in our case gasoline, react with oxygen (O2) with added heat to create carbon dioxide gas (CO2) and more heat.

This already allows for some very useful observation: first, combustion needs oxygen in a most fundamental way. You can think of a car’s engine as a large air pump, drawing in massive amounts of air, delivering it through a combustion process that consumes the oxygen, and pushing the deplete product out the other end. In fact, to burn a single gallon of gasoline completely, an engine needs to draw in nearly 9,000 gallons of air. This need to provide a ready supply of oxygen for combustion is a critical criterion and definitive challenge of any engine’s performance.

The second observation is that combustion is a process, not an instantaneous event. The heat resulting from the reaction, on the right side of the equation above, is the same heat that feeds the continuation of the reaction on the left. So, what we get in the engine is absolutely not an explosion, but a rapid combustive expansion that defines a wave of pressure, more like a push than a bang. This wave is often called a flame front, fed by the combustion of gasoline, and propagating a swell of pressure that can be converted by the engine into rotational energy. If we can accelerate that flame front, while keeping it controlled and even, we can achieve greater power from combustion. But, if we lose control of the combustion process, and perhaps even get more than one flame front from multiple points of ignition, the result is closer to an explosion, reducing performance while potentially harming the engine. Before we see how this all plays out in a typical engine, we’ll need to understand a bit more about the chemical that fuels this process—gasoline.

What Is Gasoline?

The equation above is a bit too simple. After all, we’re not burning single-carbon molecules. We’re burning gasoline. Which raises the question, what exactly is gasoline? Gasoline is a ‘hydrocarbon’, which means it is a long chain of carbon connected to hydrogen. Essentially, the longer the chain, the more potential energy it contains. Crude oil comes in chains that could be dozens of carbon atoms long. But long molecules like this, while they have plenty of potential energy in them, are thick, hard to pump, and hard to burn. Think of tar. So, we need to refine these long, heavy hydrocarbons into shorter chains of lighter hydrocarbons that are easier to burn—that’s gasoline (Image 1.1).

To make long carbon chains of crude oil into smaller chains that can be burned by our engine, we need to break them apart into smaller chains, a process called cracking. Cracking entails putting these long crude oil molecules in a tall tank, applying heat, pressure, and a chemical catalyst to encourage a reaction, and breaking them up into smaller chains of carbon. The sweet spot for our purposes is 4–12 atoms long for gasoline or 13–20 atoms for diesel. So, gasoline is not really a single chemical compound, it is an irregular mixture of different lighter and heavier compounds, with chemical characteristics that vary.

As we start thinking about putting that gasoline in our engine, it’s useful to have a sense of how the fuel performs, or more precisely how easily it ignites. Not all fuels are the same. Some might not ignite very easily at normal pressure and temperature. This is the case with diesel, for example. Others might be more volatile and ignite easily, like butane lighter fluid. If a fuel is heated or put under pressure, it might even ignite on its own, called autoignition. If this happens before we want it to in an engine, the result can be very bad.

To help us manage this potential problem, we’ve developed a way to compare the tendency of a fuel to ignite on its own when put under pressure. To do this, we compare it to a set standard, a defined hydrocarbon chain length that we can use to measure and compare other hydrocarbons. Since the molecules in gasoline are typically 4–12 carbon atoms long, we can use a strand that’s eight atoms long as a good comparison. Because a hydrocarbon with eight carbon atoms is called octane, we call this the octane rating, and use octane’s ability to withstand compression before spontaneously igniting as a guide. If a given fuel can be squeezed to 85% of the value of octane before autoignition, we give it an octane rating of 85. If we can squeeze it more, to say 105% of octane, we give it a rating of 105. Pretty simple. So, the commonly held misbelief that higher octane fuel contains more energy or power is simply not correct.

IMAGE 1.1

Hydrocarbon.

Hydrocarbon.

A chain of carbon atoms (black) and hydrogen atoms (white) make up a molecule of gasoline. This particular molecule has eight carbon atoms, so it’s a molecule of ‘octane’. Crude oil is comprised of much longer molecules that must be broken, or ‘cracked’, into smaller components to make gasoline.

Moving beyond the simple notion of an idealized perfect combustion, what does the combustion of gasoline really look like? Since gasoline is actually a mixture of many different hydrocarbons, the answer’s tricky. But for the sake of simplicity, let’s pretend it’s all pure octane. A chemist would write the resulting equation like this:

This looks complicated, but it’s really not. Notice the eight under the ‘C’ on the left; that tells us it’s octane. Simple chemistry tells us that a complete reaction, in which every molecule of gasoline is combined with the right amount of oxygen, would take place with a mixture ratio of 14.7 to 1. This means that under normal conditions 1 g of gasoline can combine with 14.7 g of air to produce a perfect oxidation reaction. This ratio is called the stoichiometric ratio. It’s often represented by the Greek letter lambda—λ. When the mixture has more fuel than the stoichiometric mix, λ is less than 1, and when there’s more air than the stoichiometric ratio, λ is greater than 1.

But this ideal ratio isn’t always ideal. For example, providing a rich mixture, with more fuel than the 14.7:1 ratio, can offer more power or easier ignition, since there is more gasoline available. At cold start-up, for example, an engine might run more smoothly with a ratio of 12:1 (or λ = 0.8) until it warms up. Or under high loads or high acceleration, we may also want a richer mixture to provide more power. Alternatively, when driving on a highway without much need for power, we would be using much more gas than we need with such a rich mixture, so we could use a lean mixture with less gasoline to improve fuel economy, say 24:1 (or λ = 1.55).

An additional complication is that we’re not providing pure oxygen to this reaction, we’re proving air. While air is about 21% O2, it’s 78% nitrogen, or N2. So far, we’ve ignored the nitrogen because it’s not part of the oxidizing reaction. But, if the heat and pressure of combustion rise too high, as a result, for instance, of heavy torque demand, nitrogen molecules break apart and combine with oxygen, usually producing nitrogen oxide (NO), but also a bit of NO2, collectively called nitrogen oxides or NOx. Nitrogen oxides are a primary cause of smog and when combined with water in the atmosphere, can form nitric acid, a cause of acid rain. Similarly, if we’re providing more fuel than can be effectively burned, some gas will slip through without burning; we call these unburned hydrocarbons (UHCs). An ongoing challenge then is to keep the heat of combustion controlled and the mixture correct to minimize these undesirable pollutants.

The Engine

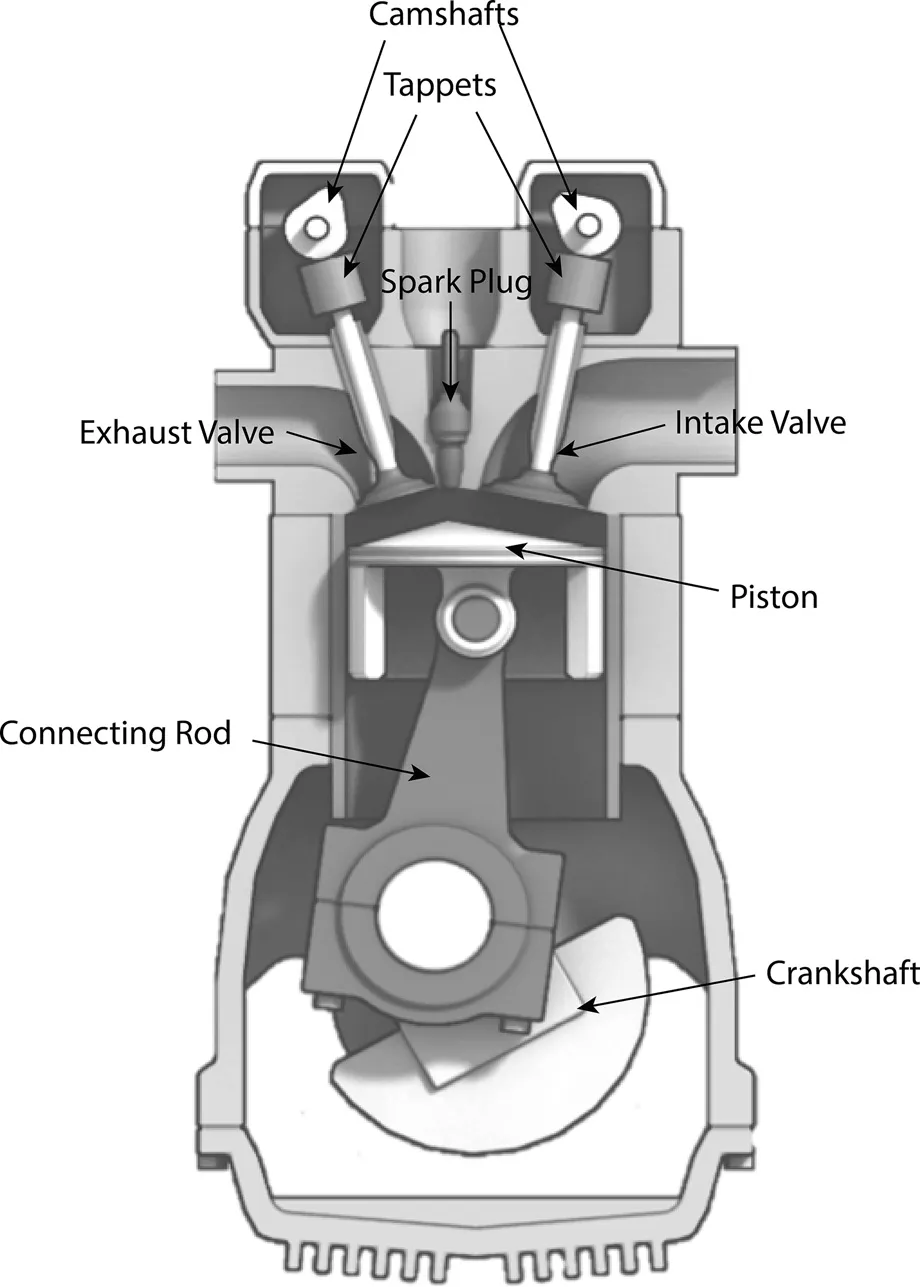

The basic components of an internal combustion engine are simple: a cylinder that’s just a long tube closed on one side and open on the other, and a piston that can slide up and down in that cylinder. These two components define the combustion chamber. We add a couple of valves that open and close to let us deliver air and fuel into the cylinder and let exhaust out. And we can add a means of mechanical connection to the bottom of the piston, so when it moves up and down, it causes a shaft to rotate (after all, what we’re after is rotation) (Image 1.2).

IMAGE 1.2

Basic engine components.

Basic engine components.

A basic internal combustion engine has some key primary components: a piston, a cylinder, a cylinder head, valves in the head, a connecting rod, and a crankshaft. In this case, our simple engine has dual overhead cams that operate the valves.

Image: Richard Wheeler

The piston is connected to a connecting rod by a pin (a piston pin), and the connecting rod is connected to an off-center, or eccentric, lobe on a shaft. When the piston goes up and down, the shaft rotates. Rotating that crankshaft is the whole purpose of the engine. So, all we need to do now is make the piston go up and down; that’s where combustion comes in. A combustion event in the cylinder when the piston is all the way up will push the piston down and turn the crankshaft. To keep that process going, in an even and regular cycle so that the shaft spins evenly and with power, we’ve defined a four-stroke process.

The Four Strokes

The basic up and down movement of the piston is defined in four strokes; that’s why we call it a ‘four-stroke’ engine. Each stroke is one full movement of the piston up or down. So, in four strokes, the piston has gone up and down twice. Let’s look at each of these strokes.

We can begin with the intake stroke. During this stroke, the piston moves from the top of the cylinder to the bottom with the intake valve open. This allows an air and fuel mixture to be drawn into the combustion chamber as the crankshaft turns a half rotation. We call that incoming air–fuel mixture a charge (Image 1.3).

As the crankshaft continues to turn, the intake valve closes and the piston is pushed up, compressing the charge. This is called the compression stroke. This adds pressure to the fuel–air mixture, resulting in a rise in heat, preparing the fuel for combustion.

With the fuel–air mixture compressed, and the piston nearing the top of the compression stroke, a spark plug is used to create a small electric arc that ignites the mixture. With combustion initiated, a pressure wave begins at the spark plug and rapidly travels through the combustion chamber. This defines a flame front that pushes strongly down on the piston, adding...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Author

- 1. Bringing the Fire

- 2. The End of Compromise

- 3. Getting Power to the Pavement

- 4. Electric Machines

- 5. Electrified Powertrains

- 6. The Electric Fuel Tank

- 7. Automotive Architecture

- 8. The Power of Shape

- 9. Smarter Cars

- Index