eBook - ePub

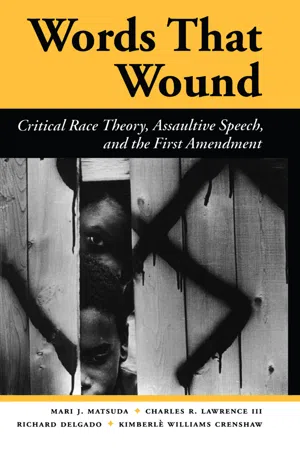

Words That Wound

Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech, And The First Amendment

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Words That Wound

Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech, And The First Amendment

About this book

In this book, the authors, all legal scholars from the tradition of critical race theory start from the experience of injury from racist hate speech and develop a theory of the first amendment that recognizes such injuries. In their critique of "first amendment orthodoxy", the authors argue that only a history of racism can explain why defamation, invasion of privacy and fraud are exempt from free-speech guarantees but racist verbal assault is not.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Words That Wound by Mari J Matsuda,Charles R. Lawrence Iii,Richard Delgado,Kimberle Williams Crenshaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

This is a book about assaultive speech, about words that are used as weapons to ambush, terrorize, wound, humiliate, and degrade. Of late, there has been an alarming rise in the incidence of assaultive speech. Although this is hardly a new phenomenon—hate speech is arguably as American as apple pie—it is a social practice that has gained a new strength in recent years. Incidents of hate speech and racial harassment are reported with increasing frequency and regularity, particularly on American college campuses, where they have reached near epidemic proportions. The National Institute Against Prejudice and Violence in its 1990 report on campus ethnoviolence found that 65 to 70 percent of the nation’s minority students reported some form of ethnoviolent harassment, and the number of college students victimized by ethnoviolence is in the range of 800,000 to 1 million annually.1

In response to this outbreak of hate speech, many universities and other public institutions have enacted regulations prohibiting speech that victimizes racial minorities and other historically subordinated groups. These regulations have prompted a heated and wide-ranging public debate over the efficacy of such regulations. Many believe that hate speech regulations constitute a grave danger to first amendment liberties, whereas others argue that such regulations are necessary to protect the rights of those who have been and continue to be denied access to the full benefits of citizenship in the United States. This debate has deeply divided the liberal civil rights/civil liberties community and produced strained relations within the membership of organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Those civil libertarians who favor restrictions on hate speech find themselves in a distinct minority. They are called “first amendment revisionists” and “thought police.” It is not a coincidence that the strongest sentiment for regulating hate speech has come from members of victimized communities. Persons of color, women, gays, and lesbians are disproportionately represented among those who support the sanctioning of hate speech, and the Jewish community is sharply divided on this issue.

This book is a collection of essays written by four of the leading advocates of public regulation of racially abusive hate speech. We do not attempt to present all sides of this debate. Rather we present a dissenting view grounded in our experiences as people of color and ask how those experiences lead to different understandings of racism and law. Our purpose here is to analyze a pressing public issue from within the emergent intellectual movement called critical race theory. In so doing we hope to provide our readers with insights that will be helpful to them as individuals, policymakers, and students of theory.

How has this book come to pass? What is the common ground that unites the work of the four authors? Are there generic themes, shared stories? Is there an ideology that makes our disparate work a whole? How and why is our work different from that of our white colleagues on the left or of those who describe themselves as liberals? What distinguishes our position from that of politicians and theorists on the right who have called for restrictions on speech?

The answers to these questions begin with our identities. We are two African Americans, a Chicano, and an Asian American. We are two women and two men. We are outsider law teachers who work at the margins of institutions dominated by white men. The identity that defines us, that brings our work together and sets it apart from that of most of our colleagues, is more complex than the categories of race and gender imposed upon us by a world that is racist and patriarchal. It is an identity shaped by life experience: by what parents and neighbors taught us as children; by our early encounters with the more blatant forms of segregation and racial exclusion and the contemporary confrontations with less obvious forms of institutional and culturally ingrained racism and sexism that face us each day; by our participation in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s and 1970s; and by the histories of the communities from which we come.

Our identities are also defined by choice. Each of us has chosen to identify with a tradition of radical teaching among subordinated Americans of color. The historian Vincent Harding describes this tradition as a vocation of struggle against dehumanization, a practice of raising questions about the reasons for oppression, an inheritance of passion and hope.2 We inherited this tradition from parents and grandparents and from countless others who have resisted racial oppression, but Harding’s description begins with the word “vocation.” The inference is that one must choose to accept the gift and the burden of this inheritance. One must choose to embrace the values of humanism. One must choose to engage in the practice of liberationist teaching. One must make that choice each day. It is this voluntary association with the struggle that is the most important part of our common identity.

What Is Critical Race Theory?

Teachers of color in the legal academy who choose to join this tradition of radical teaching have sought, in their teaching and scholarship, to articulate the values and modes of analysis that inform their vocation of struggle. These efforts have produced an emerging genre known as critical race theory Critical race theory is grounded in the particulars of a social reality that is defined by our experiences and the collective historical experience of our communities of origin. Critical race theorists embrace subjectivity of perspective and are avowedly political. Our work is both pragmatic and utopian, as we seek to respond to the immediate needs of the subordinated and oppressed even as we imagine a different world and offer different values. It is work that involves both action and reflection. It is informed by active struggle and in turn informs that struggle.

Critical race theory cannot be understood as an abstract set of ideas or principles. Among its basic theoretical themes is that of privileging contextual and historical descriptions over transhistorical or purely abstract ones. It is therefore important to understand the origins of this genre in relation to the particulars of history. Critical race theory developed gradually There is no identifiable date of birth, but its conception can probably be located in the late 1970s. The civil rights movement of the 1960s had stalled, and many of its gains were being rolled back. It became apparent to many who were active in the civil rights movement that dominant conceptions of race, racism, and equality were increasingly incapable of providing any meaningful quantum of racial justice. Individual law teachers and students committed to racial justice began to meet, to talk, to write, and to engage in political action in an effort to confront and oppose dominant societal and institutional forces that maintained the structures of racism while professing the goal of dismantling racial discrimination.

The consciousness of critical race theory as a movement or group and the movement’s intellectual agenda were forged in oppositional reaction to visions of race, racism, and law dominant in this post-civil rights period. At the same time, both the movement and the theory reflected assertions of a commonality of values and community that were inherited from generations of radical teachers before us.

Group identity forms in a way similar to individual identity. Its potential exists long before consciousness catches up with it. It is often only upon backward reflection that some kind of beginning is acknowledged. The same holds true of intellectual influences. Some influences are so significant that they become transparent, they fade into what becomes the dominant picture. Often it is not until one engages in a conscious reconstruction, asking what led to what else, that a history is revealed or, perhaps more accurately, chosen.

Kimberlè Crenshaw places the social origins of what was to become critical race theory at a student boycott and alternative course organized in 1981 at the Harvard Law School. The primary objective of the protest was to persuade the administration to increase the number of tenured professors of color on the faculty. The departure of Derrick Bell, Harvard’s first African-American professor, to assume the deanship of the law school at the University of Oregon had left Harvard Law School with only two professors of color. Students demanded that the law school begin the rectification of this situation by hiring a person of color to teach “Race Racism and American Law,” a course that had been regularly taught by Bell, who was also the author of a ground-breaking text on the subject. When it became apparent that the administration was not prepared to meet their demand, students organized an alternative course. Leading academics and practitioners of color were invited each week to lecture and lead discussion on a chapter from Bell’s book.

This course served as one of several catalysts for the development of critical race theory as a genre and movement. It brought together in a common enterprise many of the legal scholars who were beginning to teach and write about race with activist students who were soon to enter the ranks of teaching. Kimberlè Crenshaw, then a student at Harvard, was one of the primary organizers of the alternative course. Mari Matsuda, a graduate student at the law school, was also a participant in the course. Richard Delgado and Charles Lawrence were among the teachers invited to give guest lectures. The course provided a forum for the beginnings of a collectively built discourse aimed at developing a full account of the legal construction of race and racism in this country.

The Harvard course was not the only place where teachers and students gathered to engage in this new enterprise. There were conferences, seminars, and study groups at law schools across the nation. A small but growing group of scholars committed to finding new ways to think about and act in pursuit of racial justice began exchanging drafts of articles and course materials. We gave each other support and counsel by phone, as each of us struggled in isolation in our own institutions. We met in hotel rooms before, during, and after larger law school conferences and conventions. Slowly a group identity began to take shape.

Some of us sought intellectual community in what was then the dominant progressive movement in the law schools, critical legal studies. Critical legal studies, originating among a predominantly white group of law professors identified with the left, had attracted a small but significant group of scholars of color who were, to varying degrees, alienated from dominant liberal approaches to the law and legal education and were looking for both progressive allies and a radical critique of the law. Many of these colleagues on the white left had worked with us during the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s and some of them continued to be important sources of support to our efforts to integrate law school student bodies and faculties and make law school curricula and legal scholarship more responsive to the needs of subordinated communities of color.

Even within this enclave on the left we sometimes experienced alienation, marginalization, and inattention to the agendas and a misunderstanding of the issues we considered central to the work of combating racism. Scholars of color within the left began to ask their white colleagues to examine their own racism and to develop oppositional critiques not just to dominant conceptions of race and racism but to the treatment of race within the left as well.

By the mid-1980s this motley band of progressive legal scholars of color had produced a small but significant body of scholarship, and a sense of group identity began to emerge. This group identity grew out of shared values and politics as well as the shared personal experience of our search for a place to do our work, for an intellectual and political community we could call home. Our identity as a group was also formed around the shared themes, methodologies, and voices that were emerging in our work.

We turned to new approaches. Borrowing from and critiquing other intellectual traditions, including liberalism, Marxism, the law and society movement, critical legal studies, feminism, poststructuralism/postmodernism, and neopragmatism, we began examining the relationships between naming and reality, knowledge and power. We examined the role of liberal-capitalist ideology in maintaining an unjust racial status quo and the role of narrow legal definitions of merit, fault, and causation in advancing or impairing the search for racial justice. We identified majoritarian self-interest as a critical factor in the ebb and flow of civil rights doctrine and demonstrated how areas of law ostensibly designed to advance the cause of racial equality often benefit powerful whites more than those who are racially oppressed. Our work presented racism not as isolated instances of conscious bigoted decisionmaking or prejudiced practice, but as larger, systemic, structural, and cultural, as deeply psychologically and socially ingrained.

New forms of scholarship began to emerge. We used personal histories, parables, chronicles, dreams, stories, poetry, fiction, and revisionist histories to convey our message. We called for greater attention to questions of audience—for whom were we writing and why? None of these methods was unique to our work, but their frequent use by scholars of color as a part of a race-centered enterprise indicated the emergence of a genre or movement. It was this 1980s generation of liberation scholarship that came to be known as critical race theory.

In a search for a tentative expository answer to the question “What is critical race theory?” critical race scholars have identified the following defining elements:

- Critical race theory recognizes that racism is endemic to American life. Thus, the question for us is not so much whether or how racial discrimination can be eliminated while maintaining the integrity of other interests implicated in the status quo such as federalism, privacy, traditional values, or established property interests. Instead we ask how these traditional interests and values serve as vessels of racial subordination.

- Critical race theory expresses skepticism toward dominant legal claims of neutrality, objectivity, color blindness, and meritocracy. These claims are central to an ideology of equal opportunity that presents race as an immutable characteristic devoid of social meaning and tells an ahistorical, abstracted story of racial inequality as a series of randomly occurring, intentional, and individualized acts.

- Critical race theory challenges ahistoricism and insists on a contextual/historical analysis of the law. Current inequalities and social/institutional practices are linked to earlier periods in which the intent and cultural meaning of such practices were clear. More important, as critical race theorists we adopt a stance that presumes that racism has contributed to all contemporary manifestations of group advantage and disadvantage along racial lines, including differences in income, imprisonment, health, housing, education, political representation, and military service. Our history calls for this presumption.

- Critical race theory insists on recognition of the experiential knowledge of people of color and our communities of origin in analyzing law and society. This knowledge is gained from critical reflection on the lived experience of racism and from critical reflection upon active political practice toward the elimination of racism.

- Critical race theory is interdisciplinary and eclectic. It borrows from several traditions, including liberalism, law and society, feminism, Marxism, poststructuralism, critical legal theory, pragmatism, and nationalism. This eclecticism allows critical race theory to examine and incorporate those aspects of a methodology or theory that effectively enable our voice and advance the cause of racial justice even as we maintain a critical posture.

- Critical race theory works toward the end of eliminating racial oppression as part of the broader goal of ending all forms of oppression. Racial oppression is experienced by many in tandem with oppression on grounds of gender, class, or sexual orientation. Critical race theory measures progress by a yardstick that looks to fundamental social transformation. The interests of all people of color necessarily require not just adjustments within the established hierarchies, but a challenge to hierarchy itself. This recognition of intersecting forms of subordination requires multiple consciousness and political practices that address the varied ways in which people experience subordination.

Critical Race Scholars Enter the First Amendment Debate

How is it that the four authors whose essays appear in this book have found themselves at the center of the debate on assaultive speech? What has drawn us to this work? How has our identity and our political identification shaped the way we think about the first amendment?

Our entry into the contemporary discourse on assaultive speech and the first amendment is impelled and informed by the practice of liberationist pedagogy and by the emerging discipline of critical race theory. We joined this dialogue at different times and places. We focus on different aspects of this complex problem and suggest different solutions, but all of the work in this book is part of a larger project that we share. All of us found ourselves increasingly drawn into writing, speaking, and engaging in public debate as incidents of assaultive speech increased in recent years. We did not enter this debate to demonstrate our skill at intellectual swordplay Nor did we become involved because it had become a faddish hot topic. Assaultive speech directly affected our lives and the lives of people for whom we cared: family, friends, students, and colleagues.

Our work is a pragmatic response to the urgent needs of students of color and other victims of hate speech who are daily silenced, intimidated, and subjected to severe psychological and physical trauma by racist assailants who employ words and symbols as part of an integrated arsenal of weapons of oppression and subordination. Students at Stanford, at the universities of Wisconsin and Michigan, at Duke and Yale and UCLA needed protection from the most flagrant forms of verbal abuse so that they could attend to their schoolwork. Political organizers in Detroit and Alabama, working men and women breaking color and gender barriers in factories and police forces, needed to have their stories told. Our colleagues of color, struggling to carry the multiple burdens of token representative, role model, and change agent in increasingly hostile environments, needed to know that the institutions in which they worked stood behind them.

Each of us knew that we were inclined to be more cautious, less outspoken and visible, after a rash of hate tracts had appeared in our mail or been stuffed under our doors. We knew that we walked more quickly to our cars after late nights at the office and glanced more often over our shoulders as we jogged the trails around our campuses. We needed theory and analysis to articulate and explain our reality, to deconstruct the theories that did not take our experience into account, to let us know that we were not crazy, to make a space for our voices in the debate.

For example, Charles Lawrence’s chapter “If He Hollers Let Him Go: Regulating Racist Speech on Campus,” began as an effort to articulate the injury and exclusion experienced by Black students at Stanford in the wake of what became known as the Ujamaa incident.3

Two white freshmen had defaced a poster bearing the likeness of Beethoven. They had colored the drawing of Beethoven brown, given it wild curly hair, big lips, and red eyes, and posted it on the door of an African-American student’s dorm room in Ujamaa, the Black theme house. The two whi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Public Response to Racist Speech: Considering the Victim’s Story

- 3 If He Hollers Let Him Go: Regulating Racist Speech on Campus

- 4 Words That Wound: A Tort Action for Racial Insults, Epithets, and Name Calling

- 5 Beyond Racism and Misogyny: Black Feminism and 2 Live Crew

- 6 Epilogue: Burning Crosses and the R. A. V. Case

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Book and Authors

- Index