- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the Vietnam War, the United States embarked on an unusual crusade on behalf of the government of South Vietnam. Known as the pacification program, it sought to help South Vietnam's government take root and survive as an independent, legitimate entity by defeating communist insurgents and promoting economic development and political reforms. In this book, Richard Hunt provides the first comprehensive history of America's "battle for hearts and minds," the distinctive blending of military and political approaches that took aim at the essence of the struggle between North and South Vietnam.Hunt concentrates on the American role, setting pacification in the larger political context of nation building. He describes the search for the best combination of military and political action, incorporating analysis of the controversial Phoenix program, and illuminates the difficulties the Americans encountered with their sometimes reluctant ally. The author explains how hard it was to get the U.S. Army involved in pacification and shows the struggle to yoke divergent organizations (military, civilian, and intelligence agencies) to serve one common goal. The greatest challenge of all was to persuade a surrogate--the Saigon government--to carry out programs and to make reforms conceived of by American officials.The book concludes with a careful assessment of pacification's successes and failures. Would the Saigon government have flourished if there had been more time to consolidate the gains of pacification? Or was the regime so fundamentally flawed that its demise was preordained by its internal contradictions? This pathbreaking book offers startling and provocative answers to these and other important questions about our Vietnam experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pacification by Richard A Hunt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

An Insurgency Begins

The end of French colonial rule in 1954 resulted in the partition of Vietnam. North Vietnam's leadership sought to unify the Vietnamese under its rule. To accomplish this end, the leaders in Hanoi in the late 1950s turned to insurgency. Adhering to the tenets of revolutionary warfare of Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong, as modified by Vietnamese leaders such as Truong Chinh, Ho Chi Minh, and General Vo Nguyen Giap, architect of France's defeat, Hanoi built a clandestine political organization throughout the South Vietnamese countryside. Combining political appeals, terror, and guerrilla warfare, the Viet Cong sought to destroy the local outposts of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem's government and deprive it of its rural political and military base.

In the early 1950s, America devoted relatively little attention to South Vietnam. The problems of this small, distant land were relatively unimportant compared to the grave situations in Europe and Korea, which were perceived as vital to national interests, where the United States directly faced communist military forces. Concerned with the spread of communism in Asia, the American government bolstered the fledgling Diem regime with military and economic aid to help preserve South Vietnam as an independent and noncommunist nation.

The North Resumes the Struggle

During World War II, Vietnamese revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, the founder of the Indochinese Communist Party, formed the Vietnam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi (League for the Independence of Vietnam), or Viet Minh as it was commonly called, as a nationalist resistance organization. In August 1945, it briefly replaced departing Japanese occupation forces, establishing a short-lived Democratic Republic of Vietnam that claimed to represent all of Vietnam. After the French returned to power in 1946, the Viet Minh successfully waged insurgent warfare to end colonial rule but failed in its objective of attaining an independent and united Vietnam.

The Indochinese Communist Party (renamed the Dang Lao Dong Vietnam, or the Vietnam Workers' Party), led by Ho Chi Minh, continued to fight for a unified Vietnam after 1954. The party maintained close ties with Viet Minh cadres in the South. It also trained in the techniques of revolutionary war some ninety thousand southern-based Viet Minh cadres who had moved north following the partition of the country. They later returned south and merged with those who had stayed behind to form a new insurgent force, the Viet Cong.1

Between 1954 and 1956, the Dang Lao Dong discouraged armed activity in South Vietnam—restricting cadres to limited self-defense measures and directing them to develop a political movement in the villages.2 Beginning in 1955, Diem's military and police forces, however, destroyed much of this communist political apparatus. By the end of 1957, several hundred suspected party members had been killed and an estimated sixty-five thousand arrested. The Army of the Republic of (South) Vietnam (ARVN) attacked the party's bases in the Plain of Reeds on the Ca Mau Peninsula and in War Zone D. Party membership dropped by a third from a base of five thousand. The official party histories consider these years the "dark period."3 Internal dissension over Hanoi's policies further weakened the southern revolutionaries, and for a while the survival of an organized insurgent movement seemed questionable. The Saigon government may have been justified at the time in regarding the insurgents as a minor irritant.

Beginning in 1956, the southern insurgents, the Viet Cong, started building a political organization and forming local military units in Quang Ngai province, the U-Minh forest, and the heavily populated farming regions around Saigon and in the Mekong River Delta. The Viet Cong also rebuilt its base camps in the unsettled jungles close to the capital—War Zones C and D, the Iron Triangle, the Trapezoid, and the Ho Bo and Boi Loi woods. The key base area, War Zone D, forested and difficult to penetrate, was close to the Cambodian border, yet accessible to the lower delta and the central highlands. These remote bases allowed the nascent forces to develop and operate in secret. The following year, Viet Cong forces, which numbered thirty-seven armed companies, began small-scale guerrilla operations. Several hundred government officials were assassinated.4

Only in 1959 at the party's Fifteenth Plenum of the Central Committee did Hanoi, reacting to Diem's success against the communist movement and its perception of growing popular resentment of his rule, change strategy. The success of Diem's attacks forced the party to expand and protect its forces.5 It began sending supplies and personnel southward and assumed more direct political and military leadership of the insurgency. It also ordered the insurgents to dismantle Saigon's administration in the countryside and step up attacks on government villages and outposts.6 Through a combined military and political struggle, party leaders hoped to stop Diem's campaign against them and accelerate the disintegration of the Saigon government, gaining adherents to their movement from the numbers of South Vietnamese disaffected with his rule. Throughout 1959, the level of fighting increased. In response, Saigon moved forces against base areas and began to move people into new settlements, so-called agrovilles, from villages vulnerable to communist political action.

The following year, in December 1960, North Vietnam established the National Liberation Front (NLF) of South Vietnam, an umbrella organization that included the Viet Cong and representatives of other groups opposed to Diem. Like the original Viet Minh, this ostensibly broad-based organization was actually under communist control. Organized by a handful of persons affiliated with the Communist Party, the NLF drew its early membership from former Viet Minh, the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao sects, disaffected minorities (Cambodians and Montagnards), university students, some farmers in the delta, anti-Diem intellectuals, and others who, for one reason or another, opposed the Saigon regime. The NLF served several purposes. It allowed the party to attract a broad spectrum of dissident elements into the insurgency and exercise control of rival opposition groups. In setting up the NLF, the communists sought to make it the focal point for all antigovernment activity.7

The communists slowly transformed the NLF into a shadow government, with political cells extending from the village level, through district and province political committees, to a clandestine central authority. Communist Party members, however, dominated the upper echelons of the NLF's political apparatus, and the Politburo in Hanoi directed its policies, goals, and strategy. The party's success in establishing a united front with no visible ties to the communist government in the North gave the party enormous political and propaganda advantages. Under Hanoi's control, the NLF successfully projected the image of an autonomous and indigenous group. This widely held public impression had, William Duiker perceptively concluded, "momentous effects on the worldwide image" of the Viet Cong,8 identifying it as a legitimate political alternative to the government of South Vietnam. The image of the front as a southern opposition group also enabled Hanoi to sow confusion about the nature of the struggle in Vietnam. Hanoi's effort to unify Vietnam could be attributed for propaganda purposes to an internal struggle among South Vietnamese political groups.

To establish this rival government, or infrastructure, inside South Vietnam, the communists relied on measures of repression and reform. They carefully blended a campaign of terror against government officials, a skillful organizational effort that unified the movement, and promises of reform.9 Communist recruiting and organizational techniques at the local level were both simple and pragmatic. Communist organizers moved into a village, seeking to build popular support by promising to redress local grievances against landowners and the government. Cadres established local political councils that addressed specific grievances. Cadres worked through the local peasant leadership and sought adherents from a broad range of social and economic groups to solidify ties between the party and the peasants.10

Next came the crucial step, the use of violence—assassination or kidnapping or local officials—to uproot the government. According to one party member, the purpose of terrorism was to eliminate known opponents and intimidate the peopie.11 The insurgents would execute unpopular officials in full view of assembled villagers as punishment for alleged crimes "against the people." In other instances the party publicly forced local officials to humiliate themselves by denouncing the government and confessing their "guilt." Staged confessions nullified an official's worth in the eyes of villagers. The party was more circumspect in dealing with popular officials, however, eliminating them secretly to avoid arousing public resentment.

Lacking adequate territorial security and police forces, rural government officials were especially vulnerable to such tactics. The loss of representatives in the countryside, Saigon's symbols of authority as well as sources of information on rural conditions, put the Diem government in the position of "legislating in a void," to use Bernard Fall's apt phrase. In this way the communists sought to break the ties between the peasants and the central government, creating the impression that Saigon had neither the will nor the ability to protect its own people.12 The daily presence in the village of the party's political or military personnel was in marked contrast to the sporadic appearances of government officials or soldiers, so that a villager, even if he or she distrusted the revolutionaries, probably had little choice but to go along with them. The government's thinly spread forces were often not close or strong enough to protect the peasants from reprisals.13

Communist cadres drew rural settlements into a larger organization. Cadres trained some villagers in communist tactics and techniques, eventually assigning them missions outside their immediate locales and raising some to more responsible positions in the hierarchy. The cadres' recruiting program was successful. An analysis of interviews of captured enemy personnel concluded that most peasants supported the National Liberation Front because the cadres had approached and mobilized the villagers.14 Control of a village gave revolutionary leaders tangible advantages. They exacted taxes in kind, usually rice, to help feed their military forces. The levying of taxes was a sure manifestation of the party's governing authority.

Control of villages also allowed the Viet Cong to build up guerrilla forces. They generally fell into two categories: full-time regulars and part-time paramilitary forces. Full-time forces consisted of both main force and local force units. Main forces were organized into divisions and regiments, which generally operated at the national and regional levels against regular units of the South Vietnamese armed forces. Local forces were less heavily armed and fought as smaller units. They were subordinate to communist political authorities in the provinces, districts, or cities where they were usually stationed and, like the main forces, had combat support and service components.

Fart-time forces, operating as guerrillas, served in the villages and hamlets. The Viet Cong organized three types of part-time forces: combat, village, and self-defense militia. Combat guerrillas were formed into platoons, squads, and cells that conducted small-scale operations at the local level. Village guerrillas were lightly armed, part-time forces. Even without weapons, village guerrillas epitomized the party's control of a settlement. Self-defense militia were generally unarmed and partly trained personnel (mostly women, older men, and children) who functioned (sometimes involuntarily) as guards and low-level service troops, helping collect taxes, dig trenches, carry supplies, and construct simple booby traps and other obstacles.15

The Viet Cong's main forces, local forces, and guerrillas were mutually supporting. Main forces provided a shield for the work of lower-level units, and guerrillas assisted and supported main force operations against ARVN. A military headquarters at each echelon exercised direct operational command of soldiers and units at that level and administrative control of those below it. Military units at all levels were subordinate to the directives of a parallel political organization, the party.

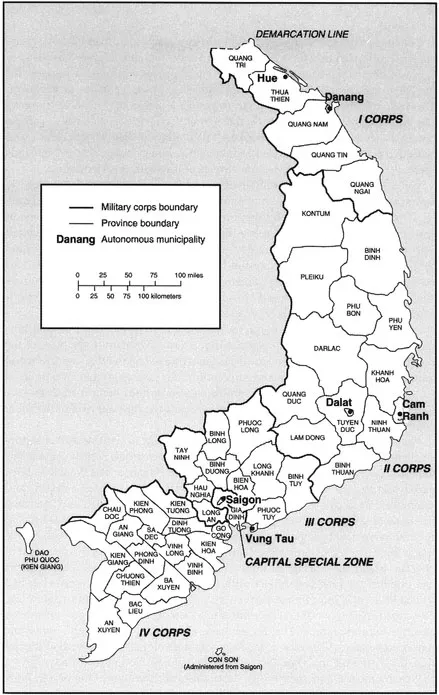

The Politburo and the Central Committee in Hanoi exercised overall control of the war effort, issuing resolutions and directives to communist organizations and leaders inside South Vietnam. To control soldiers and cadres south of the partition, the communists established a separate southern regional office in the early 1950s, the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN). COSVN was disestablished after the 1954 Geneva Accords but reactivated as the fighting intensified in 1961 and 1962. This headquarters, which moved its location several times during the war, was always relatively close to Saigon. Below COSVN, the party organized echelons of command, which were political and not military, at region, province/ subregion, district/city, and village and hamlet (see Map 1.1). COSVN controlled the territory south of Darlac and Khanh Hoa provinces, while Hanoi directly supervised the war effort in those two provinces and the area to the north. The provincial- and district-level Viet Cong administrations carried out a wide range of governmental tasks, from internal security to public health. The primacy of the party illustrated the importance that communist leaders attached to the nonmilitary aspects of their revolution. Arms served to eliminate opposition, a precondition to creating a new political order, a united Vietnam.16

In political organization and in military strength, the communists by 1959-1960 constituted a serious and growing threat to the Saigon regime's independence. As William Colby, the CIA station chief and adviser to President Diem noted later, the communists had issued no formal declaration of war in 1959 but had begun a long-term political struggle after carefully laying a solid foundation.17 They had established inside South Vietnam an organization for building a political movement and military forces based on a strategy for physically and politically isolating the regime from the people.

A House Built on Sand: South Vietnam Under Diem

South Vietnam lacked a unifying identity, a tradition of political community. Regional, ethnic, and religious antagonisms afflicted the region from its earliest days

MAP 1.1 South Vietnam administrative divisions. Source: Central Intelligence Agency, "South Vietnam Provincial Maps" (Washington, D.C.: CIA, September 1967).

as a separate nation. Between 1954 and 1956, thousands of Roman Catholics fearing persecution left the North and settled in South Vietnam. Regarded by many in Cochin China as outsiders, the Catholic émigrés proved a bulwark of support for the Diem regime and controlled many leadership positions in the government. This ruling Catholic minority sought to govern a nation that in sheer numbers was overwhelmingly Buddhist. Sizable ethnic minorities, principally Chinese (about 6 percent); ethnic Cambodians called Khmers (about 3 percent); and primitive mountain tribes, called Montagnards, living in the central highlands (perhaps 4 percent of the population) lived uneasily with the Vietnamese.

The country was divided into four corps and forty-four provinces. South Vietnam's population of roughly 16 million persons was concentrated in two large areas. Two-thirds of the people lived in the southern part of the country, the region encompassing III and IV Corps (see Map 1.1), which also contained the capital, Saigon, and, to its south, the country's main rice-growing region, the sprawling Mekong Delta. The remaining one-third of the population lived along the narrow northern coastal plains of Hue, Danang, Quang Ngai, and Qui Nhon. Large expanses of territory in the rugged central highlands of II Corps and the western reaches of I Corps were sparsely populated.

After the Geneva Accords of 1954, the government in Saigon had to establish itself as the sole legitimate political authority in South Vietnam in the place of the departing French colonists. The southern government had to offer protection and political and economic support against communist insurgents and rival political groups. Opposition from the communists as well as from the armed sects—the Cao Dai, the Hoa Hao, and the Binh Xuyen—made the early survival of the Diem regime dubious.

The heritage of French rule hampered Saigon's effort to create a workable g...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 An Insurgency Begins

- 2 Insurgency Unchecked, 1961–1965

- 3 The War and the "Other War," 1965–1966

- 4 Not by Force Alone: The U.S. Army in Pacification

- 5 The Search for Solutions

- 6 Unifying American Support of Pacification

- 7 The Early Days of CORDS, May-December 1967

- 8 Leverage: CORDS's Quest for Better Performance

- 9 The Tet Offensive and Pacification

- 10 What Next?

- 11 Abrams in Command: Military Support of the APC

- 12 The Impact of the APC

- 13 New Directions

- 14 One War or Business as Usual?

- 15 The Phoenix Program: The Best-Laid Plans

- 16 The Ambiguous Achievements of Pacification

- 17 The End of an Experiment

- A Note on Sources

- Notes

- About the Book and Author

- Index