![]()

Part I

Delineating sustainability challenges and visions

![]()

1 Sustainability

A wicked problem needing new perspectives

Carl Brønn and Peggy Simcic Brønn

Introduction

The degree of structure inherent in a decision situation is often a consideration for classifying problem types. One common framework for distinguishing problem types uses the dichotomy ‘well-defined’ and ‘ill-defined. At the extreme of ill-defined problems lies the special case of ‘wicked problems’. For organizations, the issue of sustainability is clearly an ill-defined problem within the special case constituting wicked problems: it incorporates conflicting worldviews, it is dynamic, has unclear objectives, and it is important. It is a strategic problem where the central question is ‘What shall we do?’ rather than ‘How shall we do it?’

Understanding sustainability as a wicked problem and the challenges this poses for business requires a broad perspective, one that the complex adaptive systems (CAS) view of organizations provides. The CAS perspective involves a different approach to leadership because it represents a significant shift in the mental models of both individual managers as well as the organization as a whole. It also has implications for leadership and communication. Leadership must be consistent with the constraints imposed by the dominant worldview employed in ‘managing’ the system. Thus, leaders must be aware of the importance of communication competencies when it comes to successful sustainability strategies.

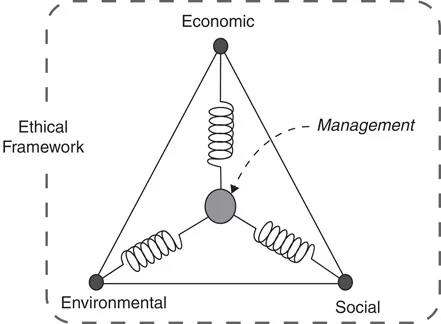

Complexity and sustainability

The United Nations 2030 agenda for sustainable development outlines a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. According to the agenda, ‘the goals and targets will stimulate action over the next fifteen years in areas of critical importance for humanity and the planet’. From the perspective of business, ‘sustainability’ is a difficult concept. One common and traditional context for addressing sustainability in the corporate world is the so-called triple-bottom line concept constituting performance evaluations along three main dimensions: financial, environmental and social. The financial dimension may include costs, revenues and growth; the social dimension fair trade, donations or employee value; and the environmental dimension wastewater, resource use, consumption, etc. Firms are expected to manage the interaction of these dimensions in a manner that is sustainable, i.e. is good for people, the planet and prosperity, all within an ethical framework. Figure 1.1 schematically illustrates the managerial challenge that is presented by sustainability. In this figure, the triangle’s vertices represent the sustainability dimensions. The three coils that connect the vertices to the circle are ‘springs’ that pull managerial attention towards each dimension. The result is an equilibrium position that depends on the relative strengths of the three springs. A relatively ‘stiffer’ spring will draw the circle towards that dimension, which results in a new equilibrium position with respect to the other dimensions.

Figure 1.1 The sustainability triad and managerial dilemma.

Traditionally, the managerial ‘equilibrium’ point, i.e. balance, has been pulled much closer to the economic corner, with historically little attention paid to the environmental and social dimensions. While the three dimensions are naturally interrelated, the primary focus of business is on economic sustainability. Two elements, hyper-growth in production rates and the focus on short-term earnings, contribute to the dominance of the economic dimension. These measures capture the notion of scope and scale, respectively. Scope represents the variety of products as measured by stock keeping units (SKU). Scale can be indicated by firms’ annual earnings.

The average urban New Yorker navigates through an economy estimated to contain 1010 SKUs (Beinhocker, 2007). This quantity represents an eightfold increase in the order of magnitude that has mostly occurred during the last 300 years. The scale of economic activity is equally impressive. Using 2011 data, Business Insider magazine (Trivitt, 2011) compared major corporations’ annual revenues with leading countries’ gross domestic products. In this ranking, Walmart Corporation’s revenues were greater than the GDP of Norway, making Walmart the twenty-fifth largest ‘country’ in the world.

Naturally, there have been reactions to this growth. The effects of resource scarcity and increased pollution have resulted in the establishment of comprehensive environmental protection laws and institutions. Similarly, the consequences on the social dimension have resulted in calls for increased corporate social responsibility (CSR). Taken together, the interactions between these three dimensions define the scope of the sustainability challenge, and the daunting task facing managers.

Organizational objectives from the traditional economic perspective of maximizing shareholder wealth are clear: a manager’s role is to identify and implement the course of action that most efficiently achieves the firm’s goal. While there may be many alternative paths to achieving that goal, there is a clear primary stakeholder, the shareholders, and a limited set of action options available to accomplish the task. This problem may be complicated, but it is well structured, or ‘tame’. When the objectives expand to include social issues such as outreach to local communities, donations to charities, codes of conduct, stakeholder inclusion, etc., managerial tasks become more difficult. There are several reasons for this. First, the lack of a clear understanding and consequently different interpretations of exactly what social issues entail stems partly from an increased set of stakeholders and their varied expectations. Most of these stakeholders do not share the shareholders’ single objective of maximizing wealth. Second, the ‘system’ that management has direct control over, the firm, now needs to be understood with respect to how it interacts with other systems, for example the local community or other institutions. These new actors introduce additional objectives that may be in conflict with the shareholders’ goals. Despite the increased complexity that social issues introduce, considerable progress has been achieved in adjusting business strategy to include it in managerial policymaking. The popularity and number of reputation measures is an indication that there is an emerging consensus on many important social performance measures.

The inclusion of the environmental dimension radically expands the complexity of the problem. While social issues in the form of CSR have the advantage of being conceptually closer to business activities, the traditional attitude towards the environmental dimension has been limited to seeing it only as a means to achieving an economic end. Extending the sustainability discussion beyond simply accessing resources to include ecological biosystems, with the attendant issues of biodiversity and the status of non-human stakeholders, introduces additional complications that are very distant from the managerial mindset and demands a view of sustainability within the special case constituting wicked problems.

Sustainability as a wicked problem

After almost 40 years, sustainability still defines itself by the statement of the UN World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (1987):

While this is an inspirational statement, the task of translating the spirit into strategy is not obvious. The absence of a more definitive expression of sustainable development has not been the fault of lack of effort. Writing in 2003, Parris and Kates (2003) reported that over 500 efforts had been devoted to developing quantitative indicators of sustainable development. They concluded that there were three primary reasons for the difficulty in achieving consensus: the ambiguity of the sustainability concept, the different purposes of measurement, and confusion over terminology and methods.

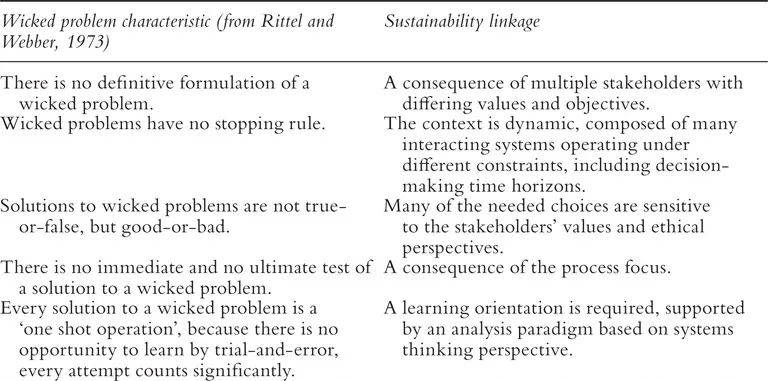

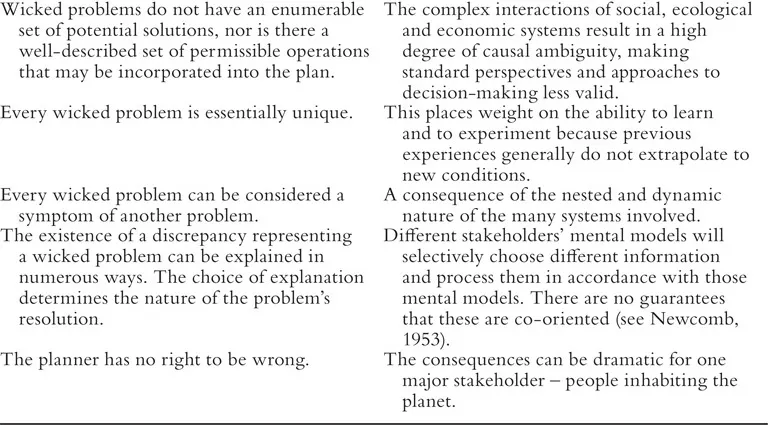

Given the nature of the sustainability challenge, these results are to be expected. This is because sustainability has all the characteristics of a class of problems called ‘wicked problems’, first categorized by Rittel and Webber in 1973. They identified ten criteria that are associated with this type of problem, all of which sustainability satisfies. See Table 1.2, which illustrates how the entire range of wicked problem characteristics affects sustainability. For example, a wicked problem is one that, among other things, has no definitive formulation. This is true for sustainability as multiple stakeholders have different values and objectives on the subject leading to different views/definitions. Wicked problems have no stopping rule; sustainability is dynamic and the time horizon is indeterminable. Every wicked problem is a symptom of another problem: issues around sustainability are consequences of nested and dynamic nature of the multiple systems involved.

Furthermore, there are no unique, clearly best solutions for wicked problems. For sustainability, the entire concept of a solution is meaningless and needs to be replaced with an appreciation that working towards a less unsustainable state (Ehrenfeld, 2005) is a continuous learning process.

Table 1.1 also clarifies that stakeholders play a prominent role in wicked problems. The effect of multiple stakeholders, all of whom are embedded in their own systems, is the tendency for everyone to be completely attentive to their own local needs, goals and actions. This intense focus, in conjunction with a simplified, event-oriented problem-solving perspective, tends to blind both external stakeholders and internal decision-makers to the unintended consequences of their actions. The result includes counterintuitive behaviours and policy resistance as other affected stakeholders attempt to meet their own objectives (Sterman, 2000).

Table 1.1 Characteristics of ‘wicked problems’ and their relationship to sustainability

By itself, a wicked problem presents decision-makers with unique challenges that do not exist in well-structured or tame problems. Structured problems have stable parameters, clearly defined boundaries, relatively few and homogeneous stakeholders, and relatively well-understood causal relationships. These all lead to a clearly recognized optimal solution. Wicked problems, in contrast, have no clear stopping point, due in part, to the presence of multiple heterogeneous stakeholders who have different and/or conflicting viewpoints and interests.

Dealing with the wicked problem of sustainability

As noted previously, sustainability is a complex, wicked problem due to two primary influences: (1) the relationships between the economic, environmental and social dimensions shown in Figure 1.1; and (2) the presence of multiple heterogeneous stakeholders. The relationships between the economic, environmental and social dimensions are not simply complicated, as represented by the number of elements in each dimension; they are complex. Removing one dimension has enormous impacts on the others. As noted by Levin (1999), ‘removing one such element destroys system behavior to an extent that goes well beyond what is embodied by the particular element that is removed’ (p. 9).

The second influence is the presence of stakeholders (referred to as ‘agents’) in the systems that make up the three dimensions. In general, agents are individuals or entities that have the ability to collect and process information and adapt their behaviour in ways that enable them to maintain desired conditions (Beinhocker, 2007). For example, in the economic system are investors and customers, the social dimension comprises communities, activist groups or employees, and the environmental system comprises various kinds of ecosystems (marine, arctic, woodlands, etc.). Sustainability arises from the interactions of these numerous types of dynamic systems. The existence of these sometimes opposing ‘agents’ require organizations to be adaptive, to be able to change over time.

Simply put, these are all dynamic systems that, according to their internal logics, attempt to harmonize with their external environments. That is, they seek an equilibrium state. In the absence of competing external influences this state is generally achieved. Sustainability considerations arise when the success of one system comes at the expense of another one. Within each of the three dimensions this competition is resolved either by accommodation or by extinction of the weaker system. This is clearly seen in the economic dimension, where it is encouraged through market competition, and in the environmental sector with predator–prey dynamics. It is also found in the social sector with the rise and fall of philosophies and religions. However, when the whole system, comprising all three dimensions, is intimately connected and mutually reliant on each other, then accommodation is the only permissible outcome. As there are many subsystems under each dimension that are involved in this world, a single stable equilibrium does not exist. Consequently, the desired ‘sustainability state’ will continuously shift in response to the innumerable individual local actions taken within each dimension. The main driver is, of course, the overwhelming dominance of activities within the economic dimension and their effects on the whole.

A complex system, as described above, that can change its structure and behaviour over time in response to changes in its environment is a complex adaptive system (CAS). While many of the principles and theory of CAS developed in the physical and natural sciences, Eidelson (1997) provides a review of applying the CAS perspective in the behavioural and social sciences, of which management theory is a part.

Applying the CAS perspective to the wicked problem of sustainability suggests a way to engage with the multidimensional aspects of organizational performance. As noted by Clemente and Evans (2014), ‘wicked problems take root and flourish precisely because they exist in a complex system that adapts to internal and external changes, and therefore wicked problems and complex adaptive systems are complementary frameworks of analysis’ (p. 5). The complex adaptive systems view, however, is not a single encompassing theoretical perspective. It describes a worldview that enables business organizations to improve their mental models of how their activities affect the broader world of social and ecological stakeholders. The deeper understanding provided by the CAS approach can contribute to aligning business strategies with the realities of the natural and social worlds that lie beyond the firm’s traditional boundaries.

Survival strategies and fitness landscapes

Organizations can no longer survive by simply adapting to today’s world (landscape) or forecasting the future based on the current situation. New survival strategies are needed and these can only be developed through application of different mental models. In the case of sustainability, radical innovation is an imperative if the vision of the UN Agenda 2030 is to be met. The CAS view offers a way to map potential survival strategies that are available to the system through the concept of a fitness landscape (Kauffman, 1995).

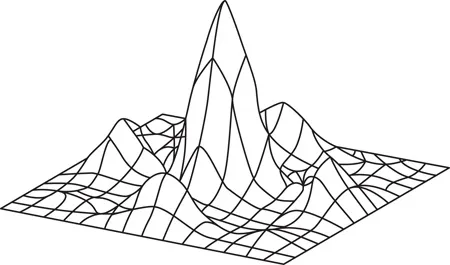

A fitness landscape is an abstract representation of the search space in an optimization problem. Graphically it has the appearance of a topographical map, as shown in Figure 1.2. The optimization problem here is that of developing business strategies for the economic dimension that are compatible with the needs, constraints and goals of the social and ecological dimensions. Every business strategy traces a path through the landscape that is defined by the three dimensions. Similarly, activities in the other dimensions also define paths through the common landscape. The fitness landscape brings out the differences in the so-called fitness of a solution to the problem under study. Those solutions that are better than others are higher on the landscape. In the case where an optimal solution does exist, it will be the highest point on the landscape where the height of a peak indicates the fitness of the system: the higher the peak, the greater the fitness.

In the search for sustainability there is no one optimal solution and the best solution at any point in time will not necessarily be best the next time. Thus, the managerial task is that of engaging with a complex process in the hope of improving the situation. The task is wicked, in part because there is no end in sight, but also because there is no agreement on what is an acceptable solution (despite the optimistic words of the UN 2030 agenda) and actions taken now will likely create new challenges in the future.

Figure 1.2 A fitness landscape (adapted from Chan [2001]).

The development of a system and its evolution can be seen as a journey through a fitness landscape in search of the highest peak that provides greatest fitness and thus the greatest chance for survival. In this journey, it is possible that the system becomes stuck on the first peak it encounters. This represents a local optimal fitness level that is better than any of the nearest neighbouring peaks. However, this local peak may not be the best possible survival strategy because, over time, conditions may change enough to require a new strategy. If the system uses an incremental improvement approach, then it may not be possible to find better peaks that are farther away from the current location. The alternat...