- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Latin America In Crisis

About this book

This book examines the intellectual problem of Latin American poverty, and discusses some of the explanations scholars have traditionally used to account for it. It focuses on its political and military dimensions of revolution and counterrevolution in the postwar era.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Latin America In Crisis by John W. Sherman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction: Why is Latin America Poor?

Latin Americans on the whole are poor, although the region also is home to some of the wealthiest individuals in the world. Mexico, for example, had twenty-four billionaires in 1994, prior to its 1995 economic meltdown—more than Britain, France, and Italy combined. But comparatively speaking, Latin America is an economically disadvantaged land. If you were randomly born into a family in the United States or western Europe, the odds are overwhelming that you would not go hungry or lack a solid roof over your head. If you had been born into a Latin American family, however, odds are about 50–50 that you would suffer malnutrition and poor health due to insufficient and unsanitary living conditions. Why is this so? Why is there such inequity among the different areas of the globe?

Social scientists have long acknowledged the economic disparities between large sections of our world. After all, such differences are conspicuous. In the early stages of the Cold War—that is, the arms race and political rivalry between the East (led by the Soviet Union) and the West (led by the United States)—people labeled regions according to their economic strength and political orientations. The industrialized and wealthy countries of the West were known as the First World, which was joined eventually by rebuilt, postwar Japan. The Soviet Union and its eastern European satellites were termed the Second World, even though their economic muscle lagged badly behind that of the West. Most of the remainder of the globe was designated the Third World—a term that survived the end of the Cold War in 1991 and is still commonly used today. Such labels have proven remarkably long-lived, although they are not particularly apt: Fat World and Thin World would be far more creative—and more meaningful—descriptions of these highly unequal regions.

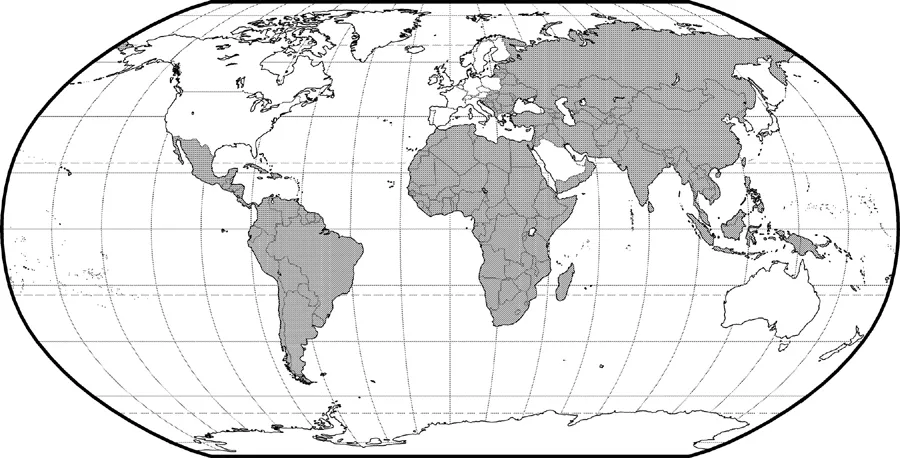

The Third World consists of nations that lack economic vitality, financial independence, and broadly shared prosperity. When the term was first coined, many also demarcated the region by its lack of industry. Today, as we shall see, some pockets of the Third World are heavily industrialized, yet still not prosperous. The Third World includes China, parts of southeast Asia, southern Asia, sections of the Middle East (e.g., Jordan and Turkey), all of Africa, and all of Latin America. Since the demise of the Soviet Union, most of the Eastern bloc has joined its ranks. Four-fifths of humanity lives in the Third World, which geographically dominates southern portions of the globe, prompting some to speak of a rich North and a poor South. Third World nations also, for the most part, are located on the outskirts of the historical core of Western civilization (Europe), and thus constitute what some refer to as a periphery.

Nations of the Third World

By the late 1950s people had begun to use another term to identify the Third World: They called it the developing world. This description is still widely used by the media and even by many academics. In the 1980s and 1990s, a number of business interests, including major banks and investment firms, supplemented this designation with a new phrase: emerging markets. Both terms, with the adjectives developing and emerging, implicitly reflect a popular interpretation of why Latin America and other parts of the Third World are poor. That is, many (especially in the First World) believe they are poor simply because they are behind on the road of time. These regions are in the process of rising to First World status: They are just now emerging and developing. Someday they will be wealthy and comfortable like us.

But is that idea, which has endured in various forms for nearly two generations, well-grounded in fact? Pondering questions of poverty and calculating future global trends are formidable tasks. Yet such activities are essential to any realistic understanding of our world, since, after all, most of humanity is still poor. By identifying the origins of the notion that the Third World is developing, and by observing some basic economic evidence, we can draw a few rational conclusions. Those conclusions, in turn, will set us on our way to discovering why Latin America is poor.

Thinking About Latin America

Beyond the realm of hard economic data and fact-based argumentation lies theory. Theories are broad models, or constructs, that attempt to explain the macroeconomic and political realities of our world. Academics use theories in order to answer the “big questions,” such as why there are such enormous inequities in global resource allocation and consumption. Although they are built upon arguments and facts, theories are by nature abstract, and they are usually engaged at such a level of intellectual sophistication (and verbalized by means of such unique vocabularies) as to remove them from the realm of popular discussion. They are one reason why—some might argue—academics are marginal players in public policy debates. Yet because Latin America has been an important case study for theoreticians, a very rudimentary understanding of some theory, even for the introductory student, is helpful. It enables one to discern the intellectual orientation of professors and books, and explains the motivation behind much scholarship.

Social scientists and just about everyone else who wrestles with the question of Third World poverty can be grossly divided into two camps: Some believe that poverty is destined to disappear over time, and others do not. Some think that in the future, Latin Americans can live just as well as those of us in the First World; some think they cannot. The first of these two viewpoints is frequently presented in the mainstream media. Political commentators like Irving Kristol, for example, have long prophesied that American-style capitalism will solve all of the world’s major problems. This interpretation had its beginnings, however, in the early years of the Cold War.

Before the ascent of the United States to superpower status following World War II, Americans—even intellectuals—were relatively unconcerned about questions of poverty in the rest of the world. In the 1950s, notions concerning development arose in the context of the new U.S. rivalry with Soviet Russia. With funding from government agencies, academics began to examine the economic and political realities of Latin America. Both the level of interest and that of financial support rose meteorically in the early 1960s, when it seemed that the region might succumb to communism and threaten the security of the United States. Al-though such studies were interdisciplinary in nature—involving a range of political, social, and economic issues—sociologists and political scientists dominated the nascent fields of theoretical inquiry.

These thinkers saw in Latin America a plethora of “backward” qualities that, they assumed, needed to change. First, the region relied heavily on agriculture and had experienced little in the way of industrialization. Second, the nature of the rural sector bothered them: It was traditional, subsistence-oriented agriculture, based on a peasant culture that had relatively few built-in market incentives. Third, those peasants lived in a hierarchical world, where status and deference were accorded to the elite owners of large estates—a society almost feudal in its demeanor, with patron-client relations instead of competitive and individualistic egalitarianism. This feudal order was reflected also in archaic political institutions: strong executive branches; little in the way of functioning legislative democracy; and loyalties that rested more on personalism, or political connections and allegiances, than on parties and ideas. These and other social features contrasted markedly with conditions in the United States. One of the presumptions of early theoreticians was that Latin America had to undergo a transformation in its political culture—or values and ideas as they relate to politics—in order to join the modern world.

A second, important assumption was that this evolutionary process was unavoidable. In the 1950s and early 1960s, the debate over whether or not the Third World was developing was, in fact, not much of a debate. Nearly everyone agreed that the whole world was moving forward (with the possible exception of the Soviets) and that the future for all humanity was bright. At the core of this general assessment emerged a school—a group of scholars united around a central idea. And this school, in turn, articulated modernization theory. Although modernization theory featured various facets and twists of meaning, at its most rudimentary level it simply held that the Third World was already on the road to modernity. Time alone assured the development of tradition-laden, simple societies. The process was unavoidable, argued scholars like Walt Rostow, who compared the process to a train rolling down a track.

Modernization theorists linked economic evolution to political change. If economic problems and political instability went hand in hand, then the opposite proposition must be true: Economic growth and well-being would fuel tolerance and a healthy exchange of ideas. In this evolution, John Johnson of Stanford University, among other academics, emphasized the role of what he termed the “middle sectors.” He foresaw that prosperity would fuel the rise of an urban middle class comprised of small businessmen, bankers, professionals, lawyers, and salesmen. Entrepreneurial and profit-oriented, these citizens, in turn, would embrace First World political values, insisting on rights similar to those found in the U.S. Constitution. The long pattern of authoritarian and often arbitrary government in Latin America would end as political institutions matured in harmony with economic and social advances.

The element of harmony was also important. Modernizationists drew on long-standing anthropological notions about society, including what is known as functionalism. Adherents of this notion believed that complex social structures, like interlocking gears, moved together in natural unison. Change in one area made change probable—even certain—in others. Thus, not surprisingly, theorists also linked economic and political transformation with culture. Indeed, they believed that much of the backwardness of the Third World was cultural. They held that modern man, in contrast to his intellectual and social predecessor (and Third World counterpart), was individualistic, efficient, resourceful, confident, and achievement-oriented. Traditional man, in contrast, was a slave to superstition, hierarchy, obedience, and fate. Latin Americans were destined to become sophisticated, modern people.

These notions of intellectual and social evolution were drawn from earlier, nineteenth-century ideologies, including positivism and social Darwinism. Positivism exuded great confidence in the rationality of humankind and in its ability to scientifically solve social ills. Social Darwinism adopted Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory (survival of the fittest) to humans and civilizations. Both positivism and social Darwinism had influenced the works of Max Weber, which in turn inspired the modernizationists. Weber had argued, at the turn of the twentieth century, that Western progress was attributable to a collection of traits embedded in the “Protestant work ethic.” Liberated from irrationality and fatalism (such as that supposedly found in Catholicism and Eastern religions), Western man had obtained the correct mind-set for advancement. Weber-influenced books, such as Edward C. Banfield’s The Moral Basis of a Backward Society (1958), paved the way to modernization theory. Building on Weber’s faith in Western man’s rationality, American scholars anticipated the rise of new cultural values in underdeveloped lands.

One modernizationist especially indebted to Weber and Banfield was Walt Rostow, who published The Stages of Economic Growth in 1960. Rostow argued that societies passed through five distinct periods on the road from backwardness to full modernity. After an era of tradition, a critical second stage followed, in which “preconditions” for modernity emerged, often taking centuries to come to completion. Then, at some point in time, a “leading (economic) sector” would grip a land and launch the third stage, a period of “takeoff”—when a nation rushed forward into modern maturity, and eventually, mass consumption.

Rostow and the modernizationists were optimistic. One reason for their confidence about the inevitability of Third World development was their faith in previous First World experience. Had not England once been primitive? Had not France and Germany, and even Soviet Russia, modernized? Rostow argued that England’s textiles were its “leading sector,” catapulting it into wealth and power. Railroads, he said, did the same for the United States, and military hardware was sparking the Soviet economic engine.

Modernization theorists, then, assumed that the poorer, “backward” regions of the globe were on a trajectory to prosperity and stability. They believed that the world was changing, prospects were bright, and the future favorable for all. If you venture into used bookstores, you can still find old atlases and travel guides that echo the refrains of modernization. Titles speak of progress and advancement. Photographs show new highways and factories, neatly dressed businessmen and modern office towers—images long associated with the First World but used to demonstrate that the Third World was coming of age. Modernization theory’s assessments and verbiage filtered into the standard high school and college texts of the 1950s and 1960s, as well—such as in the classic Latin America: The Development of Its Civilization (1968), by Helen M. Bailey and Abraham Nasatir. The dicta of modernization also found expression in popular culture. For example, in the early 1960s, as television sets appeared in American and European homes, the Summer Olympic Games became a major international sporting event, linking all of humanity in a supposed community of equal nations. That idea of global community was reflected in 1964, when the Tokyo Games ended with a salute to the spectacle’s next host: Mexico City. Yet, since 1968, neither the Summer nor the Winter Olympics have returned to the so-called developing world; poor countries simply do not have the economic resources with which to outbid rich nations that covet the prestigious and lucrative games.

Of course, television not only covered the Olympics; it also beamed images of American wealth into the living quarters of Third World residents. Whether they watched Leave it to Beaver in the 1950s or The Simpsons in the 1990s, viewers could not help but note that nearly all Americans seemed to own cars and live in spacious, two-story suburban houses. Television has largely instilled in Latin Americans the myth that all North Americans are rich. It has revealed some of the stark realities of global economics, if only by default. Shortly after television arrived in the Third World, popular impatience with such inequities began to grow. In the 1950s, Cuba—a Latin American nation plagued by stark rural poverty (and significantly, possessing one of the continent’s most sophisticated television industries)—exploded in revolution. By 1958, rebel forces led by Fidel Castro had toppled the U.S.-supported dictatorship, startling policymakers and modernization theorists alike.

Modernization theory resonated with U.S. government officials in the early 1960s, and some of its proponents helped design a response to the Cuban revolution: the Alliance for Progress. Many believed that although modernization was inevitable, it could be accelerated by technical assistance and aid packages. Rostow’s proverbial train was on the rails to prosperity, but the United States could increase its momentum by granting loans and launching nation-building programs through new organizations such as the Peace Corps. The motive for doing so, of course, was to undercut unrest and prevent more revolutions. John F. Kennedy’s administration initiated the Alliance for Progress, but also accompanied it with increased military aid. Fearing the expansion of Cuban communism (Castro turned to the Soviet Union for aid within a couple of years after acquiring power), the United States initiated counterinsurgency training programs and military collaborations with other Latin American nations.

The Alliance for Progress, established to pacify Latin America, had many mixed and unforeseen results. Stipulations required that most of the loans be spent on goods produced in the United States; heavier debt and some inflationary pressures ensued. Increased direct U.S. involvement, through a range of developmental programs from agriculture to health care and education, disrupted social relations and traditional practices, creating instability. The so-called Green Revolution, for example, begun years earlier in Mexico, accelerated crop yields (through fertilizers and chemicals), but undercut many small farmers, driving them out of business. Middle-class demands for political reform, sometimes sanctioned or encouraged by the United States, sparked fears among elites, who were ready to use their newly improved militaries to suppress any early signs of “communism.”

Despite (in part, because of) U.S. policies, there were more revolutions in Latin America in the 1960s, but none of the kind experienced in Cuba. On April 1, 1964, a momentous day for both Latin Americans and modernization theorists alike, the military in Brazil ousted the elected president from office and took control of the government. For observers the coup was not the only surprise: The new regime largely enjoyed the support of the emerging middle class! This was the very opposite of what most had predicted. Brazil’s generals dubbed their takeover a “revolution,” but there was nothing revolutionary about it. They strengthened economic policies that favored the rich and suppressed politically active, poorer Brazilians. The United States, which previously had established close ties to the military, supported the new regime. But modernization theorists in U.S. universities were puzzled. Latin America was supposed to be headed toward democracy; Brazil’s coup unexpectedly reversed a trend so many had thought they could see.

In the short term, most academics, though disturbed, concluded that Brazil was an isolated case—only a temporary setback in modernization’s progress. Many predicted that the military would restore civilian rule by the end of 1964; to their surprise, Brazil’s generals stayed in power for a quarter century. Even more shocking was that Brazil’s situation was but a harbinger of similar events elsewhere: In 1966, Argentina underwent yet another in a series of coups. In 1973, Chile, a nation with a history of relative political openness, experienced a violent takeover. By the mid-1970s, almost all of Latin America was under military rule, and the very middle classes that had been expected to promote U.S.-style democracy were, for the most part, supportive of the coups.

These unexpected developments spawned academic debate. Modernization theorists stuck to the most obvious lines of intellectual defense: Despite the militarization of Latin American regimes, they clung to their earlier predictions and downplayed evidence suggesting fundamental flaws in their theories. Some even became apologists for the new regimes. Textbook authors Bailey and Nasatir advised American college students that “undemocratic and high-handed procedures were perhaps not all bad.”1 Yet as military governments multiplied and human rights conditions worsened, intellectual evasion became all the more obvious, in the general failure to explain stark reality.

Nor was the collapse of democratic openings the only embarrassment for modernizationists. By the mid-1970s it was increasingly clear that the economic prosperity so long fore...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- 1 Introduction: Why is Latin America Poor?

- Part I Historical Latin America

- Part II Revolution and Counterrevolution

- Part III Contemporary Latin America

- Notes

- Suggestions for Further Reading

- Index