- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Politics And Society In Ukraine

About this book

With NATO expanding into central Europe, Ukraine has become a pivotal state for the future of European stability, yet it is a country about which little is known in the west. Politics and Society in Ukraine fills that gap, providing the first comprehensive and detailed study of the contemporary Ukrainian political system. Beginning with a discussion of the legacy of the Soviet Union, the authors illuminate Ukraines regional and ethnic tensions, governmental system, efforts at reform, and foreign policy. They consider all of those issues from a comparative perspective that readers unfamiliar with Ukraine will find illuminating. The authors are three of the leading authorities on Ukrainian politics, and each has extensive experience in the country. This book provides much-needed analysis of a crucial country. }With the expansion of NATO, Ukraine is frequently described as the linchpin of security in Central Europe. And after Russia, it is the largest and most important of the post-Soviet states. Yet it is a country about which most westerners know very little, subsumed as it was for decades beneath the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Ukrainian Politics and Society is the first comprehensive study of politics in post-Soviet Ukraine, and is therefore vital reading for anyone concerned with European security, or with politics in the former Soviet Union.The authors extensive experience in Ukraine allows them to explain the paradoxes of Ukrainian politics that have led to so many false predictions concerning the future of the Ukrainian state. Their examination of nationality politics shows why ethnic and regional differences have tended to recede rather than to spin out of control, as they have elsewhere in the region. At the same time, these differences hamstring the countrys political system, and the authors show how difficult a task it is for democratic institutions to provide effective government in a country with little consensus. By viewing economic reform in its profoundly political context, the authors expose the chasm between the theory and practice of economic reform. Understanding of how to make profits has not been lacking, but government regulation to ensure that profit-seeking behavior leads to functioning markets has been conspicuously absent.By examining in detail how Ukrainian politics has followed theoretical expectations and where it has contradicted them, the authors arrive at conclusions with implications well beyond Ukraine. Ukraine must first build a state and a nation before it can successfully reform its economy or build a genuine democracy. For Ukraine and its people, the task is daunting. For the west, whose security increasingly relies on stability in Ukraine, this book provides the knowledge necessary to approach the problem, as well as good reason not to ignore it. }

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Politics And Society In Ukraine by Paul D'anieri,Robert S. Kravchuk,Taras Kuzio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

PoliticaONE

The Demise of the Soviet Union and the Emergence of Independent Ukraine

The rapid and peaceful disintegration of the USSR came as a surprise to most outside observers of Soviet politics. In retrospect, it appears that the USSR would have disintegrated sooner or later because it was already in long-term imperial decline by the time Mikhail Gorbachev became Soviet leader in 1985. The rapidity of its disintegration came about as a consequence of Gorbachev's mismanagement of the economy and the increasing assertiveness of national minorities that culminated in the failed August 1991 putsch. When Ukraine and Russia decided in late 1991 that the union no longer met their interests, the USSR was doomed.

This chapter is divided into four parts. The first part provides the concise historical background of Ukraine under the late tsarist empire and the USSR. The second surveys the decay of the USSR, the rise of "national communism" in Ukraine, and Ukraine's role in the disintegration of a world superpower. The third part of the chapter analyzes the roles of Russia and Ukraine in ensuring that the USSR undertook a "civilized divorce" in December 1991. This section then discusses the hurried and largely unplanned agreement to replace the USSR with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which inevitably led to disagreements between Ukraine and Russia during the next six years. It was not until May 1997 that Ukraine and Russia finally hammered the last nail in the coffin of the USSR when they signed an interstate treaty that recognized both countries' territorial integrity. The USSR therefore disintegrated not at once—as in Yugoslavia—but in a "civilized divorce" extending over a six-year period from 1991 to 1997.1

The fourth section discusses the Soviet legacy in general and how it specifically affects politics and society in post-Soviet Ukraine. These legacies have had a profound impact upon the four transitions taking place simultaneously in Ukraine (state building, nation building, marketization, and democratization) as well as upon religion and foreign and defense policies. This discussion of the Soviet legacy places the following chapters in perspective because Ukraine, like all newly independent states, was never in a position to start its post-Soviet transformation with a clean slate. These starting points therefore affect and constrain the transformation process.2

Historical Background

Prior to the Russian Revolution, Ukrainian territories were divided between tsarist Russia (northwestern, central, eastern, and southern regions), Austria (Bukovina and Galicia), and Hungary (Trans-Carpathia).3 Ukrainians fared the worst in tsarist Russia and Trans-Carpathia. In tsarist Russia, the autonomous privileges "guaranteed" by the Treaty of Periaslav of 1654 were slowly reduced until eventually the autonomous Hetmanate was dissolved in the 1780s. Ukraine, with no serfdom and a high literacy rate that had been a source of Western cultural influences for Russia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, slowly changed, turning into a provincial backwater by the nineteenth century. Literacy rates plummeted, serfdom was introduced, and Ukrainian language and culture came under state repression after the 1860s. Ukrainians, together with Belarusians, were defined as ethnographic raw material to be homogenized into the Russian nation in the process of nation building.4

Russia, unlike France or England, had not become a nation before it became an empire. In this sense it was similar to both Austria and Turkey in the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. The late tsarist attempt to build a Russian nation drawing upon the three Eastern Slav groups proved to be impossible due to the short time frame, weakness of the modernization effort (nation building had gone hand in hand with modernization in Western Europe and North America), and incompatibility of empire and nation. A similar fate befell the Russian nation-building project in the USSR, an effort that lasted too briefly between 1990 and 1991 to complete the process. In both the tsarist empire and the USSR, therefore, a premodern Russian identity was submerged within an overall supranational imperial identification with the state, not the nation.5

In western Ukraine, the Ukrainian ethnos, or ethnic group, fared better. The exception was in Trans-Carpathia, which had come under Hungarian rule in the mid-nineteenth century and where nationality policies discouraged a nation-building project to transform the Rusyny (Ruthenians) into Ukrainians. In contrast, in Galicia and Bukovina, both under Austrian control since the late eighteenth century, the evolution of Rusyny/Ruthenians into Ukrainians had been deliberately encouraged in order to both reduce Russophile sympathies and create a bulwark against the troublesome Poles (see Chapter 2). By the 1880s in Galicia and Bukovina, three orientations were available to nation builders—a separate Eastern Slavic group (Rusyny), Little Russians (a regional branch of the Russian nation), and Ukrainians—and it was the Ukrainians who came out on top. In Trans-Carpathia, the Rusyn option was promoted by the Hungarians (who have still left their mark to this day in northeastern Slovakia), whereas in tsarist Russia, the Little Russian option was backed by the state.6

It is therefore little wonder that in 1917 "Ukrainians" were unable to create a united, powerful national movement that was able to successfully create an independent state (in the manner, for example, of the Latvians, Estonians, and Lithuanians). During the civil war of 1917-1921, pro-Ukrainian independence governments were established in Kyiv and L'viv that united Ukraine and western Ukraine in January 1919. The pro-independence Ukrainian authorities fought on many fronts against a variety of forces, including the Bolsheviks, White supporters of the Russian provisional government of 1917, and the anarchist bands of Nestor Makhno.7 In western Ukraine, conflict was severe against Poles in Galicia and Volhynia, Hungarians in Trans-Carpathia, and Romanians in Bukovina. By the time of the Treaty of Riga in 1921, Soviet Russia had retaken all of the former tsarist territories, apart from Volhynia, and had reconstituted them as the Ukrainian SSR. Volhynia and Galicia became Polish again, Trans-Carpathia went to the Czechoslovak state, and Bukovina to Romania. In all of these three states (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania), Ukrainian minorities never received the autonomy they had been promised.

After the 1921 Treaty of Riga and the Union Treaty of 1922, which created the USSR, Ukrainian lands remained divided between four states until they were annexed by the USSR in 1939 as a consequence of the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Of the four states where Ukrainians resided, they fared best in Czechoslovakia. But this state ceased to exist after Germany occupied Bohemia and Moravia in 1938, leaving Trans-Carpathia to hurriedly create its own Ukrainianophile state and declare its independence in March 1939. The ministate proved unable to maintain itself for long, as it soon fell to Hungarian forces who continued to occupy it as allies of the Germans until 1944. In Bukovina, Ukrainian forces fought an unsuccessful war against Romania in 1918-1919, and it too continued to occupy the region as a German ally until the arrival of Soviet troops in 1944.

Poor relations between Poles and Ukrainians dominated Galicia and Volhynia throughout the interwar period. Ukrainian military forces from the Austrian army put up a spirited resistance to the Poles in Galicia but by 1919 were overcome by superior Polish forces dispatched from France. The Poles reneged on their promises of substantial autonomy to Ukrainians and instead sent military colonists to settle the eastern kresy (borderlands), while occasionally initiating repressive measures against Ukrainian political and cultural life (for example, the pacification campaign of 1930). Ukrainian nationalists, many of them veterans of the unsuccessful campaign for independence of 1917-1921, organized counterviolence through the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), an integral nationalist movement created in Vienna in 1929. Poland's nationalizing policies in the interwar period toward its German, Ukrainian, and Belarusian minorities mirrored those the Prussian state had applied to Poles prior to 1918.8 Polish nationality policies replicated those of the Hungarians in Trans-Carpathia prior to 1918 and 1939-1944, in which Ukrainians were defined as regional tribes, such as Lemkos and Hutsuls. In both cases, these Polish efforts produced the opposite of what was intended, as Rogers Brubaker points out:

Yet, far from furthering the assimilation or even securing the loyalty of borderland Slavs, Poland's inept nationalizing policies and practices in the inter-war period had just the opposite effect, producing by the end of the period what had not existed at the beginning: a consolidated, strongly anti-Polish Belarusian—and to an even greater extent—Ukrainian national consciousness.9

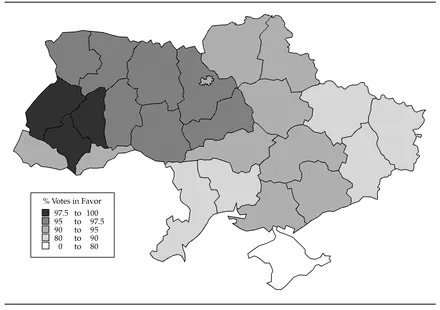

MAP 1.1 Referendum on Independence

SOURCE: Central Electoral Commission.

SOURCE: Central Electoral Commission.

It is perhaps little wonder then that by the time of the German-Soviet invasion of September 1939, one-third of the population of interwar Poland, which constituted national minorities, felt little, if any, allegiance to it. Ukrainians saw it as the chance to join in the Nazi anti-Bolshevik crusade and possibly create in the process an independent state (even a puppet one, as in Slovakia). In addition, western Ukrainians were also embittered by nearly two years of Soviet rule (September 1939-June 1941), which had turned them against Soviet power.

A joint crusade against Bolshevism and the creation of a German-aligned state, at least, was the theory. But the Nazis had other plans. The radical younger wing of the OUN led by Stepan Bandera (the OUN split in 1940 into two factions; the conservative wing was led by Andrei Melnyk) declared independence in L'viv on June 30, 1941. The result was widespread Nazi arrests of OUN members and sympathizers, including Bandera himself and Yaroslav Stetsko, who both served the remainder of the war in a Nazi concentration camp. The OUN, under its new temporary leader, Mykola Lebed, organized the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and launched a guerrilla war—first against the Nazis and, after 1943-1944, against the Soviets—which lasted until 1953. Postwar Soviet policies of forced collectivization, the forcible union of the Uniate Church with the Russian Orthodox Church (see Chapter 3), and the influx of Russian party and security functionaries all served to further alienate western Ukrainian society from the Soviet regime. The OUN-UPA struggle against the Soviet regime also served to foster an image, as in the three Baltic states, that identified the Soviet regime as "Russian" and therefore as a foreign invasion.10

At the same time, nation building in western Ukraine was fostered, perhaps unintentionally, by the Soviet regime. Due to the strength of Ukrainian national consciousness, Soviet nationality policies were not as repressive as those pursued in western Belarusia, where Soviet—not nationalist—partisans had dominated the local scene.11 Nazi and Soviet policies of genocide and ethnic cleansing removed Jews and Poles from the urban centers of western Ukraine. These urban centers expanded while others were built during the course of the Soviet modernization of western Ukraine after 1945. Urbanization and modernization consequently occurred simultaneously, with the influx of already highly nationality-conscious rural Ukrainians into the urban environment. Unlike in eastern and southern Ukraine, therefore, ethnic Ukrainians came to demographically and culturally dominate the urban centers of western Ukraine as was the case with other nation-building projects elsewhere in Europe. This had, of course, been the objective of national Communists in the 1920s in eastern Ukraine, but the policies of indigenization had been halted by the early 1930s (see Chapter 2).12 Similarly, in Trans-Carpathia after 1945, the very fact that the region became a part of Ukraine (albeit the Ukrainian SSR) for the first time since the Middle Ages, coupled with certain Soviet policies that encouraged a Ukrainian nation-building project, transformed Rusyny into Ukrainians, over half a century after that was permitted in Galicia and Bukovina.

To recap then, nation building in western Ukraine was fortuitous in being able to forge a modern national identity over six stages, which included:

- Transfer from Eastern Orthodoxy to a national institution, the Greek Catholic Church, in 1596. Prior to 1918 religion was an important marker of identity (in the tsarist empire all "Orthodox" people were defined as "Russians" [that is, Ruskiy]). The Uniate (or Greek Catholic) Church enabled Ukrainians to define themselves as different from both Roman Catholic Poles and Orthodox Russians.

- Favorable Austrian nationality policies between the 1780s and 1918.13

- Armed conflict with, and prior treatment at the hands of, Poles, Romanians, and Hungarians, which solidified their perception of these as hostile "others."

- The brutal Soviet annexation of western Ukraine (1939-1941) and Soviet policies after 1945, coupled with a vicious and protracted guerrilla war until 1953, which helped to define the attitude of western Ukrainians toward the Soviet regime as both "foreign" and "Russian," to be dumped when the opportunity arose. This they proceeded to do during the March 1990 parliamentary and local elections, when the Communist Party was removed from the political map of western Ukraine, and the March 1991 referendum, when western Ukraine held a third referendum of its own on independence that won an overwhelming endorsement.

- Postwar Soviet urbanization and industrialization, which enabled ethnic Ukrainians to dominate the urban centers of western Ukraine both culturally and demographically, which they had last done in the Galician-Volhynian Principality of the twelfth to thirteenth centuries.14

- Nation building, transforming Ruthenians (Rusyny) into Ukrainians, which the Austrians had encouraged in Galicia and Bukovina in the second half of the nineteenth century; this was encouraged by Soviet policies after 1945 in Trans-Carpathia, building on the growth of national consciousness in 1938-1939 when the region declared independence from Czechoslovakia.

Ukrainian-Polish relations after the Soviet-Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939 went from bad to worse. A Polish-Ukrainian civil war raged in Volhynia, where Ukrainian nationalists (of various groups) ethnically cleansed Poles. This was "justified" on the grounds that they were forced settlers from the interwar period and that the Polish partisan groups had cooperated with Soviet partisans against the Nazis and Ukrainian nationalists. Polish nationalist groups, in turn, ethnically cleansed regions such as Chelm and Podlachia, the site of the mass destruction of Ukrainian Orthodox churches in the late interwar period by the Polish authorities.

After the arrival of a puppet Polish Communist regime in 1944, Polish security forces, allied to the notorious Soviet secret police, the NKVD, struggled against the OUN and UPA until 1947. During this period, Poles were this time ethnically cleansed by their "allies," the Soviets, who removed them from western Ukraine ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- List of Acronyms

- Preface

- Introduction: The "Quadruple Transition" in Ukrainian Politics and Society

- 1 The Demise of the Soviet Union and the Emergence of Independent Ukraine

- 2 Nation Building and National Identity

- 3 Religion, State, and Society

- 4 Ukraine's Weak State

- 5 Politics and Civil Society

- 6 Economic Crisis and Reform

- 7 Foreign Policy: From Isolation to Engagement

- 8 Ukrainian Defense Policy and the Transformation of the Armed Forces

- 9 Conclusion: Problems and Prospects for Ukraine in the Twenty-First Century

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index