- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Weapons of Mass Destruction and International Order

About this book

First Published in 2005. How should the 'problem of order' associated with weapons of mass destrcution be understood and addressed today? Have the problem and its solution been misconceived and misrepresented, as manifested by the problematic aftermath of Iraq War? Has 9/11 rendered redundant past international ordering strategies, or these still discarded at our own peril? These are questions explored in this Adelphi Paper.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Weapons of Mass Destruction and International Order by William Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Concepts of international order: the antidote to enmity

That a concern over order has lain at the heart of international politics in modern times is not in doubt.1 But what meaning should the word ‘order’ carry? For understandable reasons, most International-Relations theorists have shied away from a definition.2 Instead, they agree that international order means many things, that its meaning is shaped by actors’ beliefs, interests and positions, that it is formed through an historically contingent combination of factors (structural, normative and instrumental), and that the presence of order is manifested by an ability to solve problems and manage change without upheaval.

The definitional difficulties are compounded by the need – usually disregarded – to distinguish between the general concept of order, alluded to when we say ‘there is order’, the genus of order referred to when we speak of the international order, and the various species of international order formed in particular domains or to address particular problems (regional, economic, security or otherwise). Where WMD are concerned, relations between these levels of order need to be drawn with special care. Although ‘the nuclear order’ is clearly an international order, it is intertwined with the international order, just as order at either level is informed by perceptions of general order. The awkwardness of referring to ‘the WMD order’ points to another difficulty, as the internal coherence of ‘the nuclear order’ cannot be matched when the objects of ordering differ so markedly in technology and effect. As will become evident, the gathering of a disparate set of technologies under the heading ‘WMD’ and their treatment under this single category contributed significantly to the difficulties encountered in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Rather than try to define order, it is most useful to focus attention on the problem of order, which, in the twentieth century in particular, may be seen as deriving from three linked problems of international life – those of enmity, power and legitimacy. Of the three, the problem of enmity may be considered the most fundamental – especially in a time of widespread strife such as our own – since it lies at the root of violence and war. True international order is first and foremost the antithesis of and antidote to enmity, with emphasis on the latter. The roots of enmity will not concern us here. Suffice to say that it is commonly driven by some combination of fear, ambition, grievance and, in its most intransigent form, ideological or religious disdain. Enlivened by modernity, it is this last driver of enmity that has proved so dangerous over the past century and continues to threaten even today.

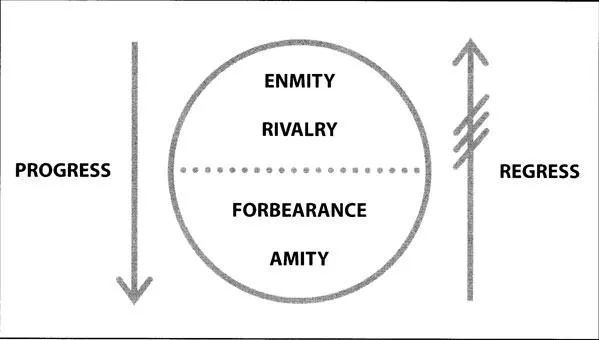

Enmity’s reduction to rivalry, forbearance and amity

Enmity implies enemies. Alexander Wendt writes that ‘enemies lie at one end of a spectrum of role relationships governing the use of violence between Self and Other, distinct in kind from rivals and friends’.3 Enmity exists when the Other chooses not to respect the Self’s right to survival as a free subject, ‘will not willingly limit its violence toward the Self’, and ‘therefore seeks to ‘revise’ the latter’s life and liberty’.4 Wendt goes on to contrast the ‘deep revisionism’ of enmity, where the Self and the Other can become caught up in a violent commitment to change, and the ‘shallow revisionism’ of rivalry, where rights to life and liberty are recognised and the Self and Other seek to revise behaviour without necessary recourse to violence.5

From this perspective, a primary objective of international ordering is to reduce enmity to a more benign and contained rivalry. More ambitiously, its purpose lies in reducing both enmity and rivalry to a sustained condition of forbearance or amity wherein states and other actors define their relations as intrinsically cooperative and strive to revise life and liberty by peaceful means alone. This journey from enmity towards amity, a striking feature of twentieth-century Europe, is illustrated in its idealised form in Figure 1. The objective of ordering is both to instigate movement down the figure from enmity towards forbearance and amity, and to lock states and other actors into those relations through a variety of political, economic and legal stratagems.6 The modem conception of order and its purpose lose conviction if the movement away from enmity is easily reversed. They rely on the construction of and commitment to irreversibility.

Since the eighteenth century, the balance of power has been the primary device for containing enmity and preventing its escalation into war. Unfortunately, there is evidence aplenty that power balancing is in itself unreliable, particularly if states are not equally committed to its sustenance, poorly led, or have unequal scope for developing their military and economic capabilities. Experience also shows that too exclusive a focus on power balancing heightens sensitivities to imbalance, which may in turn drive states into arms races and war. John Herz’s security dilemma can then, through the intrinsic instability of rivalry in a dynamic political and technological environment, become a significant structural driver of enmity among states.7 Compounding the matter, technological advance in the twentieth century and the concomitant embrace of concepts of total war dramatically increased the costs of misjudgement and breakdown in inter-state relations.

In the second half of the century, the nuclear weapon became the great power balancer, and the primary instrument of choice for reducing enmity between East and West to a survivable rivalry. At the same time, the thousands of nuclear weapons deployed in the name of power balancing exposed everyone and everything to deplorable risks. Similarly, moves by additional states to acquire such weapons threatened to destabilise regional power balances and to jeopardise deterrent relations among the established nuclear powers. As a consequence, ‘strategic stability’ and ‘non-proliferation’ became central preoccupations.

Over many decades, states responded to the march of technology (and especially of nuclear technology) by paying increased attention to the construction of what John Ikenberry has termed ‘constitutional order’ (his other two ideal types of order being ‘balance of power’ and ‘hegemonic’).8 Without turning their backs on power balancing, they sought to overcome its deficiencies by entrenching restraint through agreements on norms, rules, institutions and practices, which would guide their behaviour. Two types of constitutionalism can be distinguished: a conservative constitutionalism through which restraint is achieved by various political and legal means, without tampering with the basic norms of the state system (sovereignty being uppermost among them); and a transformative constitutionalism through which a permanent change in behaviour is sought by fundamental institutional change. The laws of war expressed in the Hague and Geneva conventions provide examples of the first type; the League of Nations and EU are examples of the second. As we shall see, the quest for control over WMD exhibited a constitutionalism that was both conservative and transformative.

The symbiosis of power balancing and constitutionalism

Whereas Ikenberry juxtaposes the power balance and constitutional approaches to international order, the two developed symbiotically during the Cold War, at least from the Cuban missile crisis onwards. Constitutionalism helped to stabilise the balance of power, which in turn forced the superpowers to accept the restraints of constitutionalism, such as the abandonment of preventive war. It was not a case of either/or. However, constitutionalism had other purposes: to facilitate reconciliation between the contrasting rights and obligations of the nuclear ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’, provide an instrumental framework for reconciling norms of sovereignty with the intrusive verification of renunciation, and offer a means of sustaining the hope of an eventual release from the threat of nuclear extinction. In this context, constitutionalism embodied the conviction that the nuclear order was the property of all states, not just the great powers, and that they collectively possessed rights to define legitimate behaviour.9

Reciprocal obligation lay at the heart of the nuclear order that emerged during the Cold War and provided the essential foundation for its claim to international legitimacy. It underpinned the balance of power and permeated the international regimes, culminating in the NPT of 1968. The stark asymmetry of capabilities that the Treaty acknowledged was compensated by a highly developed symmetry of obligations among the state parties. Furthermore, the Treaty promised (the word is not too strong) that the asymmetry of capabilities would be nullified over time by the nuclear-weapon states’ (NWS) practice of arms control and disarmament. Possession of nuclear arms was thus represented as a temporary trust, implying that the non-nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) were not locking themselves into permanent disadvantage through their acts of renunciation. Despite the nuclear order’s political and legal distinctions between nuclear- and non-nuclear-weapon states, it thus came to resemble a classical architecture in which harmony was achieved through an acute and always rational eye toward balance and symmetry. In many ways, the nuclear order’s construction assumed the ironic character of an enlightenment project.

Shifting approaches to hegemonic order

With the end of the Cold War, Ikenberry’s third type of international order – hegemonic order – began to take shape. The decline of communism drained East-West relations of enmity, just as the Soviet Union’s collapse removed for the time being the ability to balance US power. Instead, seen in the light of Figure 1, the political focus of the now pre-eminent power, the United States, shifted from reducing enmity through rivalry towards a more widespread realisation of forbearance and amity. Initially, constitutionalism was the United States’ chosen instrument for reconstituting the highly armed political entity that had been the USSR, for addressing the emerging challenges from Iraq and North Korea, and for achieving a more extensive and irreversible commitment to the inhibition of WMD, now to include universal and verified bans on CBW. This increasingly transformative constitutionalism culminated in the NPT Extension Conference of 1995 with its universalist ambitions and collective enunciation of the ‘Principles and Objectives’ that would guide the next stages.

In the first years of the post-Cold War era, hegemonic order therefore developed symbiotically with constitutionalism, giving the impression of substantial continuity in ordering strategies. In the mid-1990s and for reasons both internal and external to the US, this symbiosis began to fray, gradually to be replaced by an altogether starker conception of hegemonic order. In essence, just as the WMD order reached a pinnacle of international legitimacy, it began to fail a ‘test of efficacy’ set mainly by influential communities within the United States. Emboldened by its new-found military supremacy, encouraged by perceived difficulties in containing the diffusion of WMD capabilities in certain regions, and radicalised by the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the United States came to embrace a new approach to international order. This approach had long been advocated from the fringes, but had only briefly captured the high ground during the first Reagan administration.

The character of the new approach to order was openly displayed in the National Security Strategy published by the US government in September 2002 and in speeches and documents of the time. Its main features – the emphasis on the primacy of America’s ‘national interest’, the freedom to express enmity (or amity) and to nominate America’s friends and enemies, the downplaying of constitutionalism and multilateralism and the embrace of coercion including war – will be discussed in chapter 4. The new approach – far from the prior conception of ‘legitimate international order’ founded on reciprocal obligation and an enveloping mutual restraint – could not have taken firm root without 9/11, which dramatised the role of enmity in US relations with state and non-state actors and appeared to render previous approaches to international order threadbare and redundant. The terrorist attacks also provided an opportunity to draw previously hostile powers (notably Russia and China) into a circle of great powers united, however temporarily, by fear of Islamic radicalism.

What made all of this so unsettling to international order was that a kind of double enmity was conceived in the United States against certain actors and against certain conceptions of order. Underlying the understandable enmity against state and non-state actors that threatened vital interests, the US displayed a more disturbing enmity against constitutional order wherever and whenever it implied limits on American freedom of choice and action. This double enmity was highly evident in the campaign against Iraq in 2003, as enmity against the Iraqi regime was accompanied by an undisguised hostility towards United Nations (UN) processes regarding the search for WMD, the war’s legitimisation and Iraq’s subsequent governance and reconstruction. The resulting disturbance to international order was magnified by a pattern of behaviour evident in the defiant rejection of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), the Kyoto Agreement, the International Criminal Court and other constitutional initiatives with large international followings. Indeed, issues much wider than WMD were involved. As we shall see later, a perception grew outside the US that the problems of WMD were, in some measure, being ‘surfed’ in order to institute a new type of hegemonic order.

The United States’ recasting of its hegemonic strategy was accompanied by, and promoted through, an attack on the constitutionalism that it had done so much to develop but which influential elites had long resented and distrusted. Whilst promulgated as a means of protection against WMD, the new security strategy was deeply subversive to the prevailing WMD order. To the US administration, the latter was worthless if it could not ‘roll back’ the weapon programmes of states that defied it. To others, the turn to coercion, and the casting aside of the norms of reciprocal obligation and mutual restraint, threatened a much wider malaise. The United States’ reorientation was particularly unsettling to lesser powers given that it had hitherto respected and relied upon as the great champion of a legitimate international order founded on cooperation and shared norms.

Carl Schmitt’s three realms of enmity

In so expressing its hegemonic intent and will, the United States under George W. Bush’s presidency discarded the liberal and realist mantles of statesmen and scholars such as Dean Acheson and Hans Morgenthau, which had shaped its ordering strategies since 1945. In their place, the US adopted an interpretation of and approach to international order that bore considerable resemblance to those propounded by the German political theorist Carl Schmitt. In The Concept of the Political, published in 1932, Schmitt moved enmity into the foreground of political life, claiming that the division of social groupings into friends and enemies ‘defined the political’ since it stimulated the formation of identity and of political action on its behalf.10 In his later Theorie des Partisanen of 1962, Schmitt went further by proposing three categories or realms of enmity, which he termed ‘conventional’, ‘true’ and ‘absolute’ enmity.11

By conventional enmity, Schmitt referred to that realm in which social units (notably states) recognise each other’s rights to engage in relations of friendship or enmity and devise various individual and collective stratagems to ensure survival. They bind themselves in and through convention. From long-term interaction stems a certain regularity in the relations among competing states, which finds one of its expressions (doomed to frustration, in Schmitt’s view) in the attempts to limit or abolish war.

True enmity, in contrast, is the enmity felt by the partisan, guerrilla or terrorist group towards a powerful actor that it perceives as unjustifiably dominating a people’s territory or society and violating its identity. Such enmity is indelibly marked by asymmetry, irregularity and the absence of mercy. It is asymmetrical because the dominating power has far greater resources at its disposal. It is irregular because the opposing groups can only inflict significant injury by disregarding conventions governing the use of force, and because popular suppo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Concepts of International Order: the Antidote to Enmity

- Chapter 2 Weapons of Mass Destruction and International Order to 1990

- Chapter 3 Post-Cold War WMD Order: two Divergent Paths

- Chapter 4 The Breakdown of WMD Order

- Chapter 5 The Iraq War and Afterwards

- Conclusion: Back to Great-Power Relations