![]() Part I

Part I

Orientalism and Architecture![]()

1

Useful Knowledge

Interpreting Islamic Architecture, 1700—1840

The rest, whose minds have no impression but of the present moment, are either corroded by malignant passions, or sit stupid in the gloom of perpetual vacancy.

(Samuel Johnson, 1759)

An early nineteenth-century architect looking for recorded knowledge about Islamic architecture could have satisfied little more than the most short-lived curiosity. There was much on other forms of architecture. Since the mid-eighteenth century there had been various archaeological and rationalist projects to classify Greek and Roman architecture, and a similar attempt to understand Gothic began in the late eighteenth century after a long period of neglectful familiarity. But by contrast, the conquest of Islamic architecture by nineteenth-century scholars had little preceding it but the laconic images and reports of travellers mostly interested in other matters. Islamic architecture was seen as one of a range of natural sights and cultural artifacts. Travelogues, architectural accounts and espionage reports, therefore, often conveyed similar responses. Even the great inaugurating archive of Egypt, the Description de I'tgypt (1809-28), treated Islamic architecture as only one amongst many other subjects. Islamic culture was, anyway, regarded as a despised or lowly matter and there were few intellectual tools available to understand it.

The Description was made possible by military conquest. Likewise, the subsequent growth in knowledge about Islamic culture came about in tandem with the West's economic domination over the Ottoman Empire. Egypt and Asia Minor, especially Cairo and Istanbul, were particularly crucial areas for western interest and both had enormous strategic importance, not only economically and politically. Egypt had ancient claims as the birthplace of European culture; Istanbul could be seen as the point of its severance. Both became arenas for rival European influence, predominantly between France and Britain. Thus, in the understanding of Islamic architecture, knowledge and power were inextricable.

The main argument of this chapter is that it was only in the second quarter of the nineteenth century that architectural orientalism emerged as a distinctive cultural formation out of its two parent discourses. That this 'new orientalism' did emerge at this moment had something to do with the discarding of classical paradigms and Picturesque theory. But it had much more to do with the appeal of the new human sciences, particularly ethnography, and the operative conjunction of rationalism and modernization.

The Eighteenth Century

Most pre-nineteenth-century western travellers to the Near East went there for reasons other than architectural, and foremost amongst these reasons were trade and diplomacy. Like travellers to India and China, they collected statistics on revenue, samples of merchandise and information on military assets. In the Near East, as in India, the European attempt to survey and quantify was accompanied by the establishment of rival trading posts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The exploitation of eastern markets within a world economy was thus set in train. British trade with the Ottoman Empire was supported at state level by the granting of a royal charter to the Levant Company in 1581, and to the East India Company in 1600. Such charters gave the government a share in profits as well as some regulation over company activities. In the next century agents based in Izmir, Istanbul and Aleppo organized a sizeable trade based particularly on the exchange of woollen goods for carpets, silks and consumables. With these firm connections came a spate of travel books on the Near East - the best known were the works of Grelot, Wheler and Spon, and Maundrell - many of which were collected by architects like Wren and Hawksmoor.1

Those travellers who went to the Near East for cultural reasons, or those who mixed cultural with commercial or diplomatic purposes, usually wanted to understand the geography and civilizations of the Bible (seeing oriental customs as a continuation of Biblical life), and to explore Egypt as a palimpsest still bearing the traces of European origins. In this sense, travelling a distance was also travelling in time, and the activity of description might well be a translation of the enterprise of natural history into an observation of the cultural past. Yet although aspects of Islamic society might be reported for the charm of their exotica, overall Islamic culture was identified as only a regrettable overlay: either stagnant or corrupt, historically fixed or decaying. This was confirmed by such contemporary historical accounts as Edward Pococke's Specimen historiae Arabum (1650), the great collection of Arabic source material translated in Bartholomé d'Herbelot's Bibliothèque orientale (1697), or the 'Preliminary Discourse' written by George Sale as a preface to his translation of the Qu'ran (1734).

Outside this circle of vision few eighteenth-century travellers tried to forge a direct understanding of what they experienced or even to ask new questions of it. This was especially the case with Islamic architecture, where the canon of Graeco-Roman architecture guided the eye. In 1709 the poet Aaron Hill published A Full and just Account of the Present State of the Ottoman Empire, based on his travels in the Near East from 1699 to 1703. Like many later accounts, this set out to be an all-embracing record of its subject: a source-book of useful knowledge about the area. Chapter 17 covered 'Publick and Private Buildings in Turkey' and there Hill described baths, bans, hospitals, houses, gardens and fortifications. He itemized the typical features of a generic mosque:

Spotless white ... stately Cupola, supported by a double, sometimes treble row of Pillars of a different Order each from other, yet without a Name whereby I can express them in the British Language ... four, six, or eight tall Turrets ... A stately Portico ... tho' Images are disallowed, the compass of the inner Wall of all their Mosques is full of Niches ... Glass Lamps.2

Clearly, the problem of naming was paramount for Hill, and his solution was to inventorize, applying the nearest equivalents out of a familiar vocabulary. The other problems were that Ottoman architecture was substandard by the canons that Hill applied, and that those canons could only be partially mobilized anyway. Hill recognized this:

The Turks, unskill'd in ancient Orders of lonick, Dorick, or Corinthian Buildings, practice methods independent on the Customs of our European Architecture, and proceed by measures altogether new, and owing to the Product of their own Invention.3

But despite Hill's interest in architecture, he published no plans and his illustrations show architecture as background to some aspect of local customs, the real interest of the image.

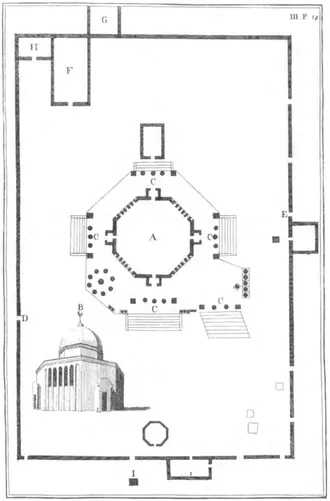

By contrast, Richard Pococke's even more compendious A Description of the East (1743—5) published schematic plans and generalized elevations and sections of several Islamic buildings: the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, the Bab al-Nasr, and 'Joseph's Hall' (the now largely demolished Qasr al-Ablaq) in Cairo; the Dome of the Rock at Jerusalem (called the 'Mosque of Soloman's

PLATE 1 Richard Pococke. Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem, 1743—5. Plan and view. (A Description of the East)

Temple') (Plate 1); and the Great Mosque at Damascus.4 In the houses that he visited Pococke was fascinated by the mechanical apparatus by which the harem was separated from the rest of the house.5 Otherwise his comments on major buildings were brief and anecdotal, as we would expect of a writer-traveller anxious not to delay his reader on the way to classical remains or the monuments of ancient Egypt. Cairene monuments were illustrated in the first volume, devoted entirely to Egypt. Here the chapter on architecture (others were on government, natural history, customs and antiquities) was entirely given over to ancient Egyptian monuments arranged in a sequence following the course of the Nile.

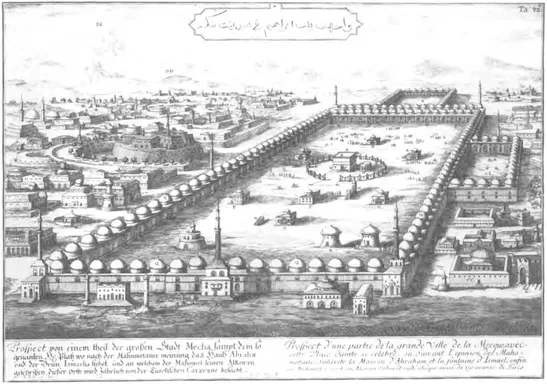

The most influential eighteenth-century work to illustrate Islamic architecture was J. B. Fischer von Erlach's Entwurff einer historischen Architectur (1721, translated into English in 1737). In his preface Fischer made his intent clear: 'Artists will see, that Nations dissent no less in their Taste for Architecture, than in Food and Raiment'. Yet there were common verities: 'notwithstanding all these Varieties, there are certain general principles in Architecture ... Rules of Symmetry; that the Weaker must be supported by the Stronger, and the like'.6 In pursuit of this variety within ruling architectural principles, the third part of Fischer's book was devoted to an extraordinary range of architecture: 'Buildings of the Arabians, Turks etc. and some Modern One's of the Persians, Siamese, Chinese and Japonese'. Amongst its fifteen plates were many unmeasured plans and perspectives, and some sections and elevations. Since Fischer never travelled outside Europe, he was dependent on the sketches and reports of travellers for these images. Of the Islamic buildings depicted, many were relatively accessible: a Turkish bath outside Budapest, the Mosque of Sultan Orcanus II in Bursa, the Mosque of Sultan Ahmet and the Suleymaniye in Istanbul. But there were also the rarely visited or totally inaccessible monuments: the Ali Qapu Palace and Maidan i Shah at Isfahan, and the mosques at Madinah and Makkah based on drawings by an Arab engineer (Plate 2). Fischer's inclusion of Islamic and other eastern buildings on a scale and with a degree of detail comparable to the illustration of more canonical ancient buildings, was to remain unique in the eighteenth century. Beyond its inevitable function as a book of illustrations to be

PLATE 2 J. B. Fischer von Erlach. Makkah, 1721. Perspective. (Entwurff einer historischen Architectur)

plundered for orientalizing garden buildings, it also indicated a new attitude towards these sources. The apparent equivalence in the status of these buildings opened up for architects the prospect of an eclecticism which was both historical and cultural, leavened by constant formal principles. But with Fischer we have moved far from the direct encounter with architecture of the eastern Mediterranean, and, because his influence in Britain was limited, far also from the particular conditions of British experience.

Early Nineteenth-Century Architects in the Near East

Before the middle of the nineteenth century most of those British architects who travelled in the Near East did so with their eyes fixed on the remains of a classical heritage. It was the lineaments of Graeco-Roman civilization that filled notebooks geared to collecting necessary professional knowledge. The usual pattern was to include Asia Minor in a tour of Greece and Italy. But although architects visited Islamic lands, Islamic architecture either simply did not exist for them or it lay outside the classical paradigm; both amounted to the same thing. C. R. Cockerell, for example, whose travels lasted some seven years from 1810 to 1817, taking in Greece, Italy, Sicily and Asia Minor, made little mention of Islamic architecture in his journal, and then either disparagingly or as a scenic but otherwise unremarkable aspect of the townscape. Typically, of Istanbul he wrote:

To architecture in the highest sense, viz. elegant construction in stone, the Turks have no pretension. The mosques are always copies of Santa Sophia with trifling variations, and have no claims to originality. The bazaars are large buildings, but hardly architectural. The imarets, or hospitals, are next in size ... but neither have they anything artistic about them.7

To some extent difficulty of access and the ad hoc nature of their trips may have helped to dissuade architects from studying Islamic buildings. (By contrast, far from the classical paradigm and under direct British company rule, in India the British began to commission detailed drawings of Muslim architecture from local artists.)8

For Cockerell and for many other architects who began to practise in the first two decades of the century, Islamic architecture was imbued with the associational values of the Picturesque. Picturesque theory in the arts had widened the range of the aesthetic, sanctioning choice from a plurality of styles provided they were associated with either the character and decorum of the building type, or the meaning of a particular site or narrative programme. Islam, in this way of thinking, could be a commodity like anything else, to be enjoyed for its novelty and, like fashions, discarded when the pleasure-seeking gaze tired. Much as other styles might imply moral or poetic ideas, so Islamic was often linked to pleasure, femininity and entertainment. The neo-Islamic buildings that had been designed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries - among them a Turkish mosque and two Alhambras at Kew, S. P. Cockerell's Sezincote (1804-5) and John Nash's Royal Pavilion, Brighton (1815-23) - relied on the easy delights and connotations of Picturesque theory, which included remoteness as a value in itself. As such they could be designed from artists' images, travellers' impressions, or a book like Fischer von Erlach's; no painstaking or firsthand examination of the originals was required. William Chambers's mosque at Kew (1761) is a case in point (Plate 3). Two minarets, a crescent on the dome, and Arabic inscriptions over the doors are enough to establish its character. But the minarets are solid and without any means to reach their tiny balconies, and inside the mosque there is no mihrab and the ornament adopts a more familiar rococo manner, abandoning any pretence at Islamic inspiration.

When travelling...