![]()

CHAPTER 1

Regional Dimensions of Europe’s Unemployment Crisis

Ron Martin

Introduction

During the period from 1945 to the early 1970s, the OECD countries enjoyed what, in retrospect, appears as a ‘golden age’ in terms of their labour market performance, an era of full employment, job security, rising real incomes and increasing social equality in economic welfare and opportunity. Although there were recurring recessions when employment fell, these were essentially minor interruptions to an otherwise unprecedently buoyant labour market, and for the most part the unemployment that existed was short term and frictional. Many of the advanced countries seemed to have achieved a workable blend of economic efficiency and social equity. Western Europe in particular appeared to be successful in applying the Keynesian-welfarist economic policy model, a form of state intervention in which macroeconomic demand management was used to maintain full employment and a redistributive-tax-and-benefit transfer-based welfare system was used to limit the extremes of wealth and poverty.1

In stark contrast to that period, the past two decades have been a period of intense change and upheaval in the OECD economies. Most, if not all, of the labour market certainties and verities of the long post-war boom have been undermined. In contrast to those boom years, since the beginning of the 1980s the labour market has become characterised by increasing uncertainty, insecurity, risk and inequality. One of the most traumatic developments, without doubt, has been the dramatic rise in joblessness: the spectre of mass unemployment has once again been haunting much of the industrialised world. In the 1950s and 1960s, OECD unemployment averaged less than 10 million. During the early 1970s, however, it began to rise, and in the recession of the mid 1970s peaked at 18 million. In the next downturn of the early 1980s it rose again, very sharply, to 30 million. Strong economic expansion in the second half of the 1980s did bring some reprieve, but failed to drive the jobless total back down to the levels of the 1970s, let alone the 1950s and 1960s, and in the early 1990s recession it increased once more to reach 35 million, the highest on record. Thus in the space of two decades, between 1972 and 1992, the number of unemployed in the OECD had tripled.

At a very aggregate scale, there is a distinctive international geography to the OECD ‘jobs problem’, in that the growth of unemployment has been much more pronounced in the European Union than in the United States, the EFTA economies, Japan or the Oceania countries. These international differences have been the focus of a formidable corpus of analytical scrutiny, both by economists (for example, Burgess 1994; Freeman 1994; Glyn 1995; Jackman 1995; Krugman 1994a; Rowthorn and Glyn 1990) and by leading international organisations (European Commission 1993; International Labour Organisation (ILO) 1995; OECD 1994a,b,c). But, equally, there are marked regional and local disparities in the incidence of unemployment and labour market exclusion within individual countries. These regional and sub-regional geographies of unemployment and labour market exclusion are the focus of this book. The following chapters highlight the importance of these sub-national geographies. Although the theory of spatial labour markets and their functioning, adjustment and regulation has received increasing attention over the past few years (see, for example, Blanchard and Katz 1992; Campbell and Duffy 1992; Fischer and Nijkamp 1987; Hanson and Pratt 1992; Marston 1985; Martin 1981, 1986; Martin, Sunley and Wills 1996; Peck 1996; Topel 1986), the development of this field of enquiry is still in its infancy.2 The papers collected here not only make a valuable contribution towards this endeavour, they also provide a much-needed corrective to the characteristically aspatial approach adopted by economists to the current unemployment crisis. In both senses, the essays help to push the labour market issue into the mainstream of regional theory and policy. My aim in this chapter is to set the context for the discussions that follow by examining, in a deliberately discursive manner, some of the key regional dimensions of Europe’s unemployment problem.

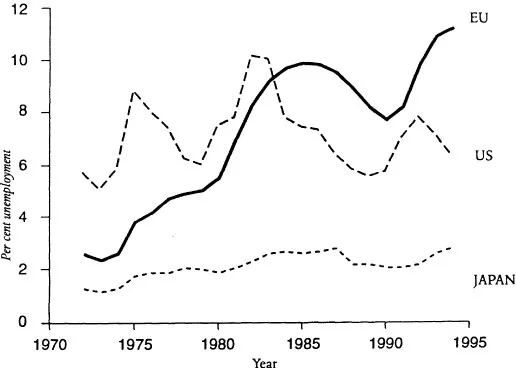

The Scale of Regional Unemployment Disparities Across the European Union

As has already been noted, the unemployment crisis is far more severe in Europe than in other parts of the advanced industrial world (see, for example, Adnett 1996; Blanchard and Summers 1986; Dreze and Bean 1990; Michie and Grieve Smith 1994; OECD 1994a,b,c; Symes 1995). Throughout the 1950s and 1960s unemployment rates tended to be much higher in the United States than in Europe. However, during the 1970s unemployment rose rapidly in Western Europe, and by the early 1980s it had overtaken the US as a high unemployment area (Figure 1.1). In 1973 the unemployment rate in the European Union was less than 3 per cent, but by 1994 it had increased to more than 11 per cent, nearly double the rate in the US and almost four times that in Japan. Moreover, neither the US nor Japan have experienced the strong upward trend that has characterised the EU since the mid 1970s, where the aggregate unemployment rate has tended to rise further, and fall less, over each successive economic cycle. Unemployment in the EU increased dramatically during the deep recession of the early 1980s and continued to increase well after the recession, up to 1985. Although unemployment fell between 1985 and 1990, when the net addition to jobs in the Union was greater that at any time over the preceding 30 years, even at its cyclical trough in 1990 it still remained well above the rate of the late 1970s. The recession of the early 1990s then saw record job losses in the EU: almost 60 per cent of the extra 10 million jobs created between 1985 and 1990 were lost between 1991 and 1994. As a result, officially recorded unemployment climbed to its record post-war level of over 18 million.3 Although the EU-wide unemployment rate stabilised at around 11 per cent during 1995 and 1996, the problem seems unlikely to decline very rapidly in the near future. As the European Commission (1995a, p.7) itself has acknowledged:

Figure 1.1: Unemployment Rates in the European Union, United States and Japan, 1972–94

Source: OECD (1994a,b,c)

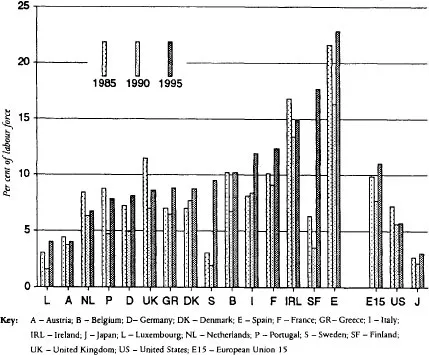

Figure 1.2: Unemployment Rates in European Union Countries, the United States and Japan, 1985, 1990 and 1995

Source: European Commission (1995a)

Note: Excludes A, GR June 1994, NL, SF April 1995, all other countries May 1995.

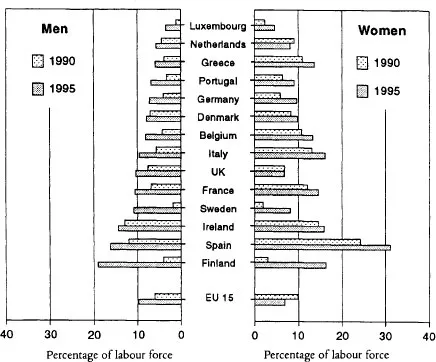

Figure 1.3: Unemployment Rates of Men and Women in European Union Countries, 1990 and 1995

Source: European Commission (1995)

Unemployment remains the major economic – and social problem confronting the Union. The means of achieving a higher rate of employment growth, sustained over a long enough period to bring the numbers out of work down to acceptable levels will, therefore, be a primary issue of policy concern for some time to come.

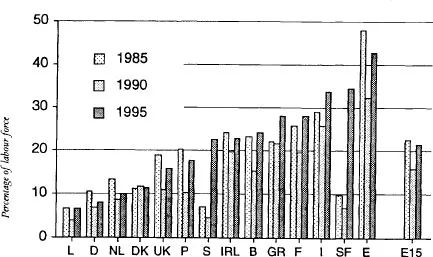

Moreover, both the scale and characteristics of the unemployment crisis in the European Union vary a good deal between countries and between regions, as do the potential for generating increased rates of job creation and the appropriate policies to pursue. In recent years, the unemployment problem has been most acute in Spain, Finland, Ireland, France and Italy – all with rates above the EU average. Belgium, the UK, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Greece, Portugal and Sweden have tended to have rates below the EU figure but higher than the USA. Austria and Luxembourg have been the exceptions to the rest of Europe in having unemployment rates even lower than the US rate (Figure 1.2). This basic inter-country pattern holds for male, female and youth unemployment. Thus while unemployment rates for women tend to higher than those for men across most of the European Union (the exceptions being Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the UK), they are highest in the Catholic countries such as Spain, Ireland and Italy (Figure 1.3). Unemployment rates among those under 25 years of age are especially high (typically double the total rates) and also vary considerably across member states: in 1994 they ranged from a low of 6.5 per cent in Luxembourg to 45 per cent in Spain (Figure 1.4).4 Across the Union as a whole, roughly one in five young people are without jobs (compared with about one in eight in the United States).

Figure 1.4: Unemployment Rates of Young People (Under 25 years) in European Union Countries, 1985, 1990 and 1995

Source: European Commission (1995a).

While these national differences are important, it is at the regional, sub-regional and urban levels that variations in unemployment incidence are particularly significant and problematic (see European Commission 1996a; Symes 1995; Tomaney 1994). Regional and local unemployment disparities, far from being an incidental feature, are an integral component of the general ‘jobs problem’, and hence also have an important bearing on understanding the nature of that problem and devising policy responses to it. For ‘national’ labour markets are, in fact, spatially fragmented entities, intricate mosaics of regional and local labour markets. These spatial sub-markets not only mediate wider national and international processes and forces in ways that reflect the local particularities of economic structure, labour force supply and institutional forms, they also stamp their own autonomous imprints on such processes: the specific labour market conditions, opportunities and barriers that individuals face are, to some extent, regionally and locally constituted. In this sense, the unemployment process and the social inequalities which it produces have an intrinsic local level of operation, with the implication that the social exclusion effects that unemployment brings are likely to be compounded by the localised concentration of joblessness. Wide spatial differences in unemployment across the Union thus pose a real challenge to the EU’s goal of social cohesion.

In addition, regional disparities in unemployment impinge upon the movement towards European economic and monetary integration. The larger are spatial unemployment disparities, the more they hinder the integration process, since regional and sub-regional imbalances in relative labour demand make it difficult to pursue growth in the Union without encountering inflation in the lower unemployment core areas of the Union well before the surplus labour in the high unemployment areas is fully utilised. But at the same time, given that productivity standards, competitiveness and monetary values will be set by the stronger core growth regions in the EU, economic integration and moves towards monetary union and a single currency will tend to exert additional adverse demand and supply pressures on the weaker, low productivity high unemployment regions. Economic and monetary union, therefore, could well exacerbate regional unemployment disparities, particularly in the absence of an EU-wide integrated system of automatic inter-regional fiscal transfers and stabilisers (see Eichengreen 1990, 1995; MacKay 1995).5 The reduction of these disparities is thus seen as necessary for successful economic and monetary integration.

The problem is that regional differences in joblessness across the EU are considerable: ‘The Union’s unemployment problem is most acute at the regional and local level. The evidence confirms that it is in terms of unemployment that regional disparities are particularly acute and show little sign of narrowing’ (European Commission 1996a, p.25).

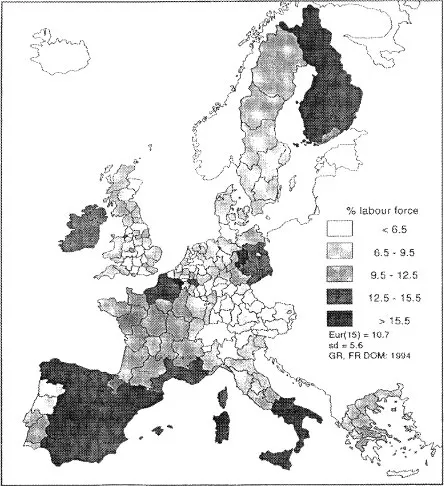

For example, in 1995 the average unemployment rate in the 25 worst affected NUTS2 regions was 22.4 per cent, nearly five times the average rate (4.6%) in the 25 least-affected regions.6 The range in unemployment rates at this regional level was from a low of 3.2 per cent in the Salzburg area of Austria to 33.3 per cent in Andalucia in southern Spain. Most of the areas with the highest unemployment rates (above 15.5%) are in the peripheral areas of the Union: in Finland, Ireland, the new German Länder, southern France, Spain and southern Italy (see Figure 1.5). These areas include economically lagging (the designated Objective 1) regions, areas of industrial decline (Objective 2 regions) and problem rural (Objective 5) localities. In contrast, most of the lowest unemployment regions (with rates less than 6.5%) tend to be more scattered across the more economically dynamic parts of the Union: in Luxembourg, southern and western Germany, Austria and northern Italy. Furthermore, there are often significant differences in unemployment rates within member states. In 1995, the difference between the least and worst affected regions was some 20 percentage points in Spain (from 13% in Navarra to 33.3% in Andalucia) and Italy (from just under 5% in Trentino-Alto Adige to 25 per cent in Campania), and almost 15 percentage points in Germany (from 4% in Oberbayern to more than 18% in Magdeburg). At a more local level, high unemployment rates also exist in some of Europe’s capital cities, prime examples being Brussels, Berlin and London. More generally, urban unemployment has been a growing phenomenon throughout Europe, manifesting itself in particular parts of cities rather than across cities as a whole. The co-existence – and often close juxtaposition – of intra-urban areas of employment growth and high incomes with other intra-urban zones of high unemployment, low incomes and high dependence on welfare benefits, has become increasingly common. Unfortunately, few comparable statistics are available across Europe to capture the detailed extent of these intra-urban disparities, but national sources point to unemployment rates of 30 per cent and more – and occasionally as high as 50 per cent – in some inner city and suburban areas.

Figure 1.5: Unemployment Rates by Region, 1995 (NUTS2 regions)

Source: European Commission (REGI0)

Not only are there marked regional and sub-regional disparities in the incidence of unemployment across Europe, there has also been a tendency for these regional differences to widen. As aggregate unemployment has risen, so the regional (and national) dispersion of unemployment rates – as measured, for example, by the standard deviation – has increased (Figure 1.6). Thus the absolute dispersion of regional unemployment rates increased sharply from 1978 up to 1985, when aggregate EU unemployment peaked, and then fell slightly during the boom of 1986–90. However, with the subsequent rise in unemployment throughout Europe during the recession of the early 1990s, regional disparities widened once more. By 1995, the dispersion of regional unemployment rates across the EU was three times what it had been in the late 1970s. These movements in the dispersion of regional unemployment disparities reflect both the tendency for high unemployment regions to exhibit a greater cyclical sensitivity than low unemployment areas (see Decressin and F...