- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Writing for Engineering and Science Students is a clear and practical guide for anyone undertaking either academic or technical writing. Drawing on the author's extensive experience of teaching students from different fields and cultures, and designed to be accessible to both international students and native speakers of English, this book:

- Employs analyses of hundreds of articles from engineering and science journals to explore all the distinctive characteristics of a research paper, including organization, length and naming of sections, and location and purpose of citations and graphics;

- Guides the student through university-level writing and beyond, covering lab reports, research proposals, dissertations, poster presentations, industry reports, emails, and job applications;

- Explains what to consider before and after undertaking academic or technical writing, including focusing on differences between genres in goal, audience, and criteria for acceptance and rewriting;

- Features tasks, hints, and tips for teachers and students at the end of each chapter, as well as accompanying eResources offering additional exercises and answer keys.

With metaphors and anecdotes from the author's personal experience, as well as quotes from famous writers to make the text engaging and accessible, this book is essential reading for all students of science and engineering who are taking a course in writing or seeking a resource to aid their writing assignments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Writing for Engineering and Science Students by Gerald Rau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Creative Writing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Getting the big picture

Chapter 1

General principles of writing

1.1 Fitting in, standing out

I currently teach at a university in a rural area in southern Taiwan. There is no written dress code, but almost everyone dresses informally. Students come to class in shorts and tee shirts, with sneakers or flip-flops on their feet. It just seems to fit the area. Someone wearing high heels and the latest fashion would seem out of place, perhaps a visitor from elsewhere. They just don’t fit. But among the informally dressed students, some stand out. They ask the right questions, work hard, and excel in class.

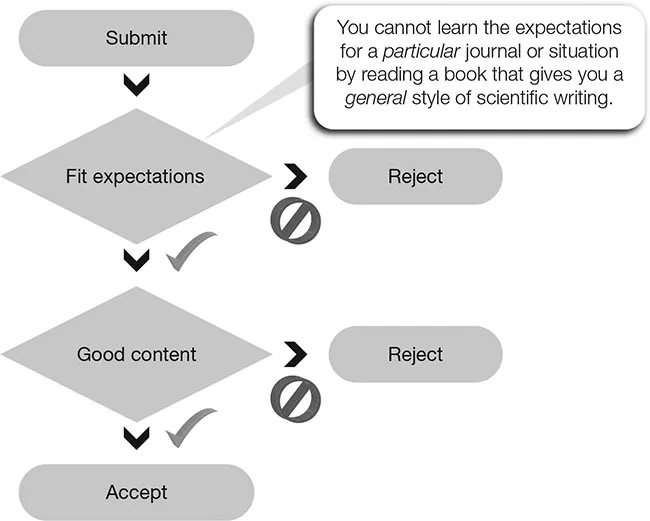

The same principle applies to writing in science or engineering, whether in academics or industry. For example, there may not be a written code that says what a research article should look like in your field, but everyone who has been in it for a while knows the unwritten rules. If you follow those rules, you will fit in. If not, they will look at you like an outsider, and your paper is less likely to be accepted. But within those papers that all look similar, some stand out. They ask the right questions, are well written, and wind up being highly cited. Nevertheless, if you don’t fit in, you never get the chance to stand out (Figure 1.1).

The problem is that when you begin to write in a new field of study, you do not know the expectations, the unwritten code. I suggest there are three ways to learn the unwritten expectations in your field:

(1) Gradually learn by experience;

(2) Ask someone with more experience;

(3) Purposefully study the structure of successful writing.

Many students choose the first route, often by default rather than active choice. They finish their research and are ready to write, but then realize they have no idea how to structure their writing. Nevertheless, they try their best, and wind up very discouraged when their teacher or advisor says they have completely missed the mark. After a number of attempts, they finally succeed, and after a few more attempts manage to master the style. Nevertheless, they may not be able to describe it to others because they have never considered what makes some writing better structurally, only in terms of content. This is also the limitation of the second route—some professors can train their students to do the research but have never studied or thought critically about how to write.

That brings us to the third route, and the purpose of this book. Every journal has its own unwritten rules that define the expected structure for articles, and you must learn what those rules are if you want your work to be accepted by that journal. Every business has similar unwritten rules for reports in that company. You cannot learn the expectations for a particular situation by reading a book that gives you a general style for a certain type of writing. You can do it by reading and working for many years and gradually assimilating the style, or you can expedite the process by actively studying the structure of good examples. In this book you will learn and practice how to do that.

Figure 1.1 Fitting in and standing out.

The method taught in this book allows you to write better, with less revision, and easily adapt your writing to meet the expectations of different situations.

The process initially will seem very tedious. At first you may wonder if it is worthwhile, but it has two advantages. The first and most immediate is that whatever documents you need to write as a student will require less revision and get higher marks, because they meet the expectations. The second and ultimately more important is that it will be easier to adapt your writing to different situations. After using the method to purposefully study journal articles, you can compare any subsequent writing task with what you already know. By noting the differences, you will be able to adjust your style of writing accordingly. If you have learned to write in one format by trial and error, you will have to use the same slow method for the second as well.

1.2 We have to start somewhere, but why research articles?

No matter what you want to learn, it pays to start with the fundamentals. Therefore, no matter what you plan to write first, we will begin with an analysis of research articles. There are four good reasons for this:

(1) You will learn to read more effectively to get the information you need to work in science or engineering;

(2) Research articles are complete arguments, thus a good example for your own writing, but also part of an ongoing research effort;

(3) Other genres of student and technical writing are predictable modifications of research article structure in that field;

(4) Research articles are readily available.

Research articles are readily available examples of good arguments; understanding their argument structure will help you read and write better.

What the American novelist Stephen King said is no less true for academic writing than fiction: “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that” (King, 2000: 147). Whether in school, academics, or industry, you will need to read research articles to get up-to-date information on the latest advances in your field. As we will see, research articles have a relatively predictable order of claims. Articles include most of the components common in science and engineering writing, and certain phrases are frequently used to mark each component. Understanding that structure and recognizing those phrases will help you locate the information you need for your own work more quickly and efficiently.

Although each research article stands alone as a complete argument, it is also part of the growing body of knowledge in that field. Thus each article is one link in a long chain of research and makes sense only in the context of that whole chain. You will need to read many articles before you can see the overall structure of that chain and understand which links are most important in holding the whole chain together, and which merely connect one item dangling from that chain like a charm on a bracelet. The same is true for technical reports, email, or any other type of writing discussed in this book.1

Furthermore, as we will see in Chapters 10–17, although other genres make different basic claims than journal articles, they include many of the same components, evidence, and reasoning and are strongly influenced by the research article structure in that field. Thus understanding the structure of journal articles will assist you with almost any type of writing.

From a practical perspective, research articles are easy to obtain. Although it is difficult to access authentic examples of industry reports, grant applications, reference letters, and many other genres because of confidentiality concerns, there is a virtually inexhaustible supply of journal articles available in any field.

1.3 Academic English: a new language

If you are a graduate student, or even an upper-level undergraduate, you have probably read an academic journal article. What was your first impression? Many students, even those whose first language is English, wonder, “Is this English? Why can’t I understand it?” The language used in journals is very different from the language of everyday speech.

“Is this English? Why can’t I understand it?” Academic English is not anyone’s first language.

Linguists (those who study the structure and use of language) tell us that there are many different genres of writing. Genre refers to a specific category of written, spoken, musical, or artistic presentation, and each genre has its own style. Academic English is different from everyday English, and each discipline even has its own discipline-specific English, with its unique vocabulary and expressions. Technical writing is not the same as academic writing in the same field. The technique we will be using in this book is based on genre analysis. It will help you learn to both read and write academic and technical English, particularly the discipline-specific English of your field.

Since academic English is not a first language for any of us, this book should be useful to any beginning writer. As with learning any other new language, it will take time, but the principles taught in this book will help you improve faster. Eventually you will learn to not only write but also think in the patterns expected in your field.

1.4 Identifying good exemplar articles

The best exemplar is one that is well written and has a good argument structure, not the one closest to your topic, most cited, or written by the top researcher.

Throughout the book you will be examining exemplar articles. As the name imp...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- To the Student

- To the Teacher

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1 Getting the Big Picture

- Part 2 Argument Structure in Exemplar Articles

- Part 3 Exploring Different Genres

- Part 4 Creating Your Masterpiece

- Part 5 Adding the Final Touches

- Appendix 1: Generalized Component List

- Appendix 2: Concordance, Academic Word List, and Related Tools

- Appendix 3: List of Supplemental Material (Online)

- Glossary

- Index