![]()

1

Introduction

In this chapter, I introduce how digital technology is transforming the music score. The purpose is to understand how the digital score presents a different set of propositions and signatures to the notion of a music score, and therefore is to be considered as a new type of music communications interface worthy of its own tradition of inquiry. The first section discusses the nature of the term digital and overviews ways in which it has transformed the notion of a music score. I offer a brief historic perspective of how the music score was transformed from a place of documentation to a space for creativity, and how digital technology is transforming this creative space again. I argue that the digital score is a direct response to a need to communicate ideas within this new emergent space and utilises the interactivity of technology to facilitate such engagements. This is because older, traditional methods of scoring are no longer able to support shifts in the interests, practices and technologies of a new music culture that innovates, explores and expands its creativity through digital technology.

The next section analyses the digital score as a transformational creative space for music-making. I outline many of the creative concerns and activities associated with the digital score and highlight the transformations of practice that are discussed in detail in later chapters. Following this, I explain my findings from the preparatory practice-based experimentation with the digital score that led to the creation of this book. Then I discuss how the concept of a digital score is already reaching outwards into the wider culture and industries of music. I conclude this section with an outline of some of the problems, complexities, redundancies and entropies of the digital score.

The final section explains what is in the rest of the book. By way of introduction, I describe three strong beliefs that have underpinned my approach. The first is that ‘to music is to take part’,1 with my discussions on music having been considered from the perspective of doing music. From this, I briefly explain that I have adopted Small’s notion of musicking.2 Second, I note that I have conducted the research using a practice-based approach3 and have deliberately sought to understand the digital score from inside the creativity of musicking. And, lastly, I explain that I am not seeking to argue for the digital score to be a new paradigm different from the traditional score, but to highlight the new creative opportunities that this new context affords in musicking. This is followed by a chapter-by-chapter breakdown articulating the theoretical proposition of this book.

Transformations

The term digital can be prepended to many things in order to highlight a transformation into something other while maintaining a grounding in its analogue sibling: digital pianos, digital books, digital publishing, even a digital motor.4 The digital score is no different: the music score transformed by the digital.

The term brings with it an optimistic essence about being future-looking, contemporary, innovative and interactive. The digital can be distributed rather than confined; it can be mercurial and in-the-moment. It suggests flexibility, adaptability, un-fixedness and extensibility insofar that the design is in the computational domain and is therefore easy to revise with updates. Developments in the digital realm are rapid as they slip easily from prototype, through alpha and beta testing to a real, distributed work; and then back again in an iterative circle of creativity and enhancement through user experience.

Powerful data processing speeds and the miniaturisation of computer architecture is enhancing interactive experiences through usability, adaptation and intelligence. Added to this is the mixed-media functionality of laptops, tablets and smart phones, which offer collaborations between screen, sound, midi, video tracking, gesture, haptic controller, stereoscopic visual display, in-glasses displays, networking and other technologies that are yet to emerge.

All these factors are transforming the digital score into something more than merely a screen displaying images of paper scores; as such, it is proving to be a more flexible and malleable concept for communicating ideas in music. This stimulates new relationships between musicians and opens up the possibilities of new creative experiences. For example, some are created in order to get musicians closer to a type of interactive relationship between the immediacy of the composed idea and performance practice. Others are interested in incorporating twenty-first-century culture and technology such gaming, social media, laptops, coding, open source, interactivity and distributed communication, to name but a few (see Figure 1.1). Others want to express compositional ideas and performance practices that cannot be represented using existing concepts of the score; some are reacting to the dominance of the paper-based score as the only format for publishing; and others are looking for more efficient ways to make music. Creative approaches to the digital score are transforming existing corpus (e.g. animated scoring systems); composition methods (e.g. working with artificial intelligence); performance environments (e.g. integrated cross-disciplinary performance); and music-making engagement (e.g. telematics performance linked through distributed scores).

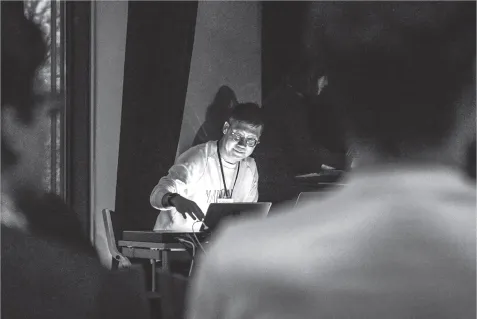

Figure 1.1 Kiyoung Lee and Ha-Young Park (not pictured) performing their digital score Four by Four (4 × 4) (2017) at Kyma International Sound Symposium, Oslo 2017.

The Digital Score as a New Communications Interface

In most music cultures, there is a score system of some sort that operates as a communication interface between musicians.5 Scores have been around for a long time6 and have been of great benefit to the practitioners that adopt them.7 Their resilience, reliability and continued use8 are such that they can be considered ‘facts of musical life’.9

Over the course of hundreds of years,10 and as music cultures embraced different code-systems, musicians utilised the communication potential of scores and notation. Certain cultures ceased to be concerned with the specificity of vocal expression in favour of developing group behaviour or facilitating creativity in performance. These music codes were transformed to manage groups of people to act dependably as directed through time, aligning them into a singular enactment of an idea. Code-based documents were developed as a creative interface between the expression of a composer and managing people as a dynamic music-making system. With the specificity of utterance given over to interpretation—and perhaps trust of the performers—the purpose for the score had transformed. It had moved away from a place of documentation to a space for creativity.

Creative invention within most of these music cultures has become intrinsically linked with its score system.11 For example, the physical act of writing notes and rhythms on staves, drawing graphical representations of music gestures on the page or writing tab notation for guitarists have all sustained creative invention within these practices. This does not differ from the way oral music cultures have developed communications direct from the source. In cultures such as folk, jazz, world music and rap,12 a score of some sorts exists. This might be communicated from the memory of one musician using verbal descriptions, or in the muscle-memory of chord shapes or the hand or finger gestures on the fretboard that is then learned by rote or imitation. It might be a flowchart of chords or words or as a list of songs on the back of a beermat, each with the purpose and function of communicating ideas from within their culture. Overall, a musical idea is communicated from one mind to another, and the practices of such music-making are embedded, infused, infected with the feel and shapes of the idea to such an extent that they are capable of being re-communicated and enacted again and again through different musicians.

The contemporary common-notated score is an efficient, widely accepted system for distributing ideas in music within a certain type of context and for a certain type of musician. Its evolution has been analogous with the developments in, for example, the complexity of the tonal, harmonic, rhythmic and the textural language of music; experimentations in compositional ideas such as indeterminacy/aleatoric practice; graphical representation of sound on the page; and microtonal instruments. Recently, there have been significant developments in score writing software that support this common-notation system, with improvements in the professionalisation of this software enabling the publishing of a score direct from the computer. These software environments are exceptional at supporting the type-setting of the contemporary score, enabling files to be downloaded and distributed digitally.

But, if the compositional idea is not about a sequence of sonic events, then common-notation and traditional scores become limiting (see Figure 1.2). For example, if ideas are dealing with more emergent creative energy within the inter-relationships between sound, space, instruments and people, then a scoring system that encourages such emergent creativity needs to be invented. Or, if the music idea is of such temporal complexity that it cannot be communicated using blunt symbols vaguely anchored to a piece of paper, then a dynamic computer-based system will be required.

The digital score is a direct response to such needs and utilises the interactivity of technology to facilitate such engagements. Crucially, it is a platform that supports the contemporary musician’s curiosity towards experimentation and adaptation of contemporary technologies in their music-making. The digital score is a reflection on contemporary culture and the predominance of digital technology and communications in contemporary life. Musicians are naturally interested in expressing themselves to their community through their music. This is generally shaped by the cultural and aesthetic make-up of the individual, the community to whom their music is intended and also the collective education of the individual and the community.13 If the music ideas that are shaped by such forces are not easily expressed by ...