eBook - ePub

Quest For The Jade Sea

Colonial Competition Around An East African Lake

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this fascinating story of colonial competition around Lake Rudolf, a remote body of water in northern Kenya, Pascal James Imperato examines the political and diplomatic aspects of colonial competition for the lake as well as the many expeditions that traveled there. Although the chief competitors for the lake included the British, Italians, the French, Russians, and Ethiopians, its colonial fate was decided by Great Britain and Ethiopia. The role of Ethiopia as a late nineteenth-century colonial power unfolds as Imperato provides unique insights and analyses of Ethiopian colonial policy and its effects on the peoples who inhabited the region of the lake. }The last of the major African lakes to be visited by European travelers in the late nineteenth century, Lake Rudolf lies in the eastern arm of the great Rift Valley in present-day northern Kenya, near the Ethiopian border. Also known as Lake Turkana, Lake Rudolf is a large saltwater body two hundred miles long and forty miles wide. Fed by the Omo River that flows south from the Ethiopian highlands, it is surrounded by an inhospitable landscape of extinct volcanoes, wind-driven semidesert, and old lava flows. Because of the greenish hue of its waters, it has long been called the Jade Sea. Quest for the Jade Sea examines the fascinating story of colonial competition around this remote lake. Pascal James Imperatos account yields important insights into European colonial policies in East Africa in the late nineteenth century and how these policies came into conflict with a powerful indigenous and independent African state, Ethiopia, which itself was engaged in imperial expansion.Although the chief competitors for the lake included the British, Italians, the French, Russians, and Ethiopians, its colonial fate was decided by Great Britain and Ethiopia. The role of Ethiopia as a late nineteenth-century colonial power unfolds as Imperato provides unique insights and analyses of Ethiopian colonial policy and its effects on the peoples who inhabited the region of the lake. As well as examining the political and diplomatic aspects of colonial competition for Lake Rudolf, Quest for the Jade Sea focuses on the expeditions that traveled there. Many of these were the field expressions of colonial policy; others were undertaken in the interest of scientific and geographical discovery. Whatever the impetus, their success required courage and much suffering on the part of those who led them. Whether as willing agents of larger colonial designs, soldiers intent on promoting their military careers, or explorers who wished to advance scientific knowledge, expedition leaders left behind not only fascinating chronicles of their experiences and discoveries but also parts of the larger story of colonial competition around an East African lake.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Quest For The Jade Sea by Pascal James Imperato in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Sources of the Nile

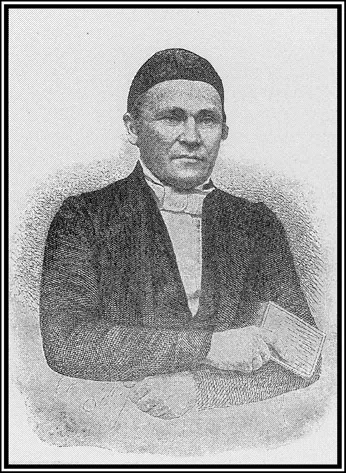

Johann Ludwig Krapf (from Travels, Researches, and Missionary Labours, 1860).

Around 140 A.D., Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy), the renowned Alexandrian astronomer and geographer, produced a map of the world. On it, he showed the Nile arising from two large lakes below the equator. These in turn were fed by streams flowing down the slopes of the snow-covered Lunae Montes (Mountains of the Moon). Ptolemy had never been to equatorial Africa but based his map and Guide to Geography on a variety of recorded sources. Among these was an account by a Syrian geographer of the first century named Marinus of Tyre. Marinus had recorded the voyage of a Greek merchant, Diogenes, who claimed to have traveled inland from the coast of East Africa for twenty-five days.

Diogenes left the coast from an emporium called Rhapta and eventually came to two lakes and a snowy range of mountains, which he said were the source of the Nile. The actual location of Rhapta is currently debatable. However, it may have been on the Pangani River or farther south in the Rufiji River delta. In either case, it appears to have been on the coast of present-day Tanzania. Given the regularity of Greco-Roman trading along the East African coast and in the Indian Ocean, it is not at all inconceivable that Diogenes had traveled inland as Marinus of Tyre claimed. There is also the possibility that the information presented by Marinus was relayed to him by Greco-Roman traders who had obtained it from their counterparts on the East African coast.1

Whatever the origins of the information contained on Ptolemy’s maps and in his Guide to Geography, it came to represent most of what was known in Europe about the source of the Nile for the next 1,700 years. It was not until around 1835 that theoretical scholars based in Great Britain began their intense studies of East Africa. These “armchair geographers,” as they are sometimes called, heavily relied on the formalistic methods of medieval scholasticism. They applied these methods to Arab, classical, medieval, and Portuguese texts in an attempt to deduce the precise geography of places they had never seen. This painstaking pursuit of geographic truth through meticulous logic was soon to come into direct conflict with the findings of those who had seen the equatorial snow-covered mountains and lakes of East Africa. Yet the armchair geographers never retreated from their deduced assertions, even when faced with overwhelming evidence gathered in the field. To have done so would have eroded the power of their established authority. However, they were quite adept at reinforcing the validity of their conclusions by claiming that certain discoveries in Africa clearly confirmed their own carefully reasoned opinions. In so doing, they did not cite the numerous instances where field observations contradicted their strongly held contentions.

British armchair geographers received their first serious challenge in 1849 when a German missionary named Johann Rebmann, working in the service of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in East Africa, reported that he had visited Mount Kilimanjaro three times in 1848 and 1849 and had seen its snow-covered peaks.2 This was threat enough to armchair theories about East African geography. However, Rebmann’s assertion was strengthened by the report of his senior colleague, Johann Ludwig Krapf, who had also journeyed into the interior from their coastal mission station at Rabai, near Mombasa. He not only corroborated Rebmann’s observations of Kilimanjaro but also reported seeing another snow-covered mountain, Mount Kenya, to the north.

The Krapf and Rebmann reports were not received by an unbiased and uninformed audience. Their chief critic was William Desborough Cooley, a prominent member of the Royal Geographical Society, who had never been to Africa. Yet at the time, he was recognized and respected as a leading authority on African geography. His authority derived from numerous publications in which he diligently analyzed the previous writings of classical, medieval, Arab, and Portuguese authors.

As Cooley saw it, Ptolemy’s Mountains of the Moon were not in East Africa and Kilimanjaro and Kenya were only a fifth the height claimed by Rebmann and Krapf. It was even suggested that Rebmann and Krapf had merely seen white rocks gleaming in the sun atop relatively small mountains.

Cooley’s views may not have been convincing enough to completely sway the leaders of the Royal Geographical Society. However, they had the effect of sowing doubt about Krapf and Rebmann’s claims. Those claims, based as they were on what Cooley characterized as “ocular testimony,” were made in an era when the society placed great store in scientific determinations of altitude, distance, latitude, and longitude. David Livingstone, who worked farther south in Africa, shared Krapf and Rebmann’s view of using geographic exploration in the interests of missionary goals. However, he employed a variety of observing and measuring instruments that gave his findings a credibility that pundits like Cooley could scarcely challenge.

Krapf did indeed possess a range of scientific instruments, given to him by the Bombay Geographical Society. But it is doubtful that he knew how to use them, and even if he did, he reported that it was impossible to do so in the presence of curious African crowds. As a result, his estimations of distances and directions fell wide of the mark and made them and his visual discoveries an easy target for Cooley’s pen.

Cooley was unrelenting in his criticisms of Krapf and Rebmann’s reports, pouring acidic comments about them onto the pages of prominent periodicals and eventually into a book entitled Inner Africa Laid Open. In this book, he characterized Krapf and Rebmann’s snow-covered mountains as myths: “With respect to those eternal snows on the discovery of which Messrs. Krapf and Rebmann have set their hearts, they have so little shape or substance, and appear so severed from realities that they take quite a spectral character.”3

Two other powerful armchair geographers entered the fray. James MacQueen was an opinionated Scotsman who had once been the manager of a sugar plantation in the West Indies.4 There, he came into contact with slaves from West Africa, from whom he learned a great deal about the geographic features of the continent’s interior. It was through their accounts and a trenchant analysis of the available literature that he correctly deduced the location of the Niger River delta in 1816.5 However, it was his experience as editor of the Glasgow Courier and his part ownership of the Colonial Bank and the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company that gave him a power base from which to project his views.

MacQueen was fairly gentle with Krapf and Rebmann. He had, in fact, previously contributed a geographic memoir to a book about Krapf’s six years as a missionary in Ethiopia.6 Nevertheless, MacQueen had very strong views about the source of the Nile, which he vigorously presented in a number of publications. He was convinced that the Nile issued from two large lakes in East Africa, an assumption that was closer to the truth than Cooley’s belief in only one.

The third member of the armchair triumvirate was Charles Tilstone Beke. Unlike Cooley and MacQueen, he had actually traveled in Africa. Primarily a businessman with international mercantile interests, he went to Abyssinia in 1840. The threefold purpose of this trip was to open up commercial links with Abyssinia, to abolish the slave trade, and to discover the sources of the Nile. Over a period of three years, Beke surveyed some 70,000 square miles of country but had little success in setting up trade with Abyssinia or in stamping out the slave trade. Beke’s scientific accomplishments in Abyssinia were truly substantial. In addition to mapping the watershed between the Nile and Awash Rivers, he meticulously collected the vocabularies of fourteen languages and dialects, as well as a number of natural history specimens.

After his return to London in 1843, Beke was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society. He once again took up his commercial pursuits and also authored many publications dealing with his scientific explorations in Abyssinia.7

Beke was no stranger to Krapf since the two had met in Abyssinia. He respected Krapf and his intellectual integrity and opined that Kilimanjaro and Kenya were part of Ptolemy’s Mountains of the Moon. He also claimed that the rivers that fed the Nile flowed from the slopes of these mountains. It was not merely friendship for Krapf that drove Beke to these conclusions; it was also a certain amount of self-interest. Based on his own survey work in Abyssinia, he had concluded that Africa had a principal mountain system running from north to south on the eastern side of the continent. He viewed the Mountains of the Moon as part of this range, the northern extent of which he claimed to have fully explored in Abyssinia. So convinced was Beke of the validity of this theory that he organized an expedition in 1849 to prove it. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, and other prominent individuals gave the expedition their patronage. Unfortunately, Beke recruited a Dr. Bialloblotsky from Hanover to lead it. Bialloblotsky was a bizarre and unsuitable character who made a very bad impression on Lieutenant-Colonel Atkins Hamerton, the British agent in Zanzibar. After consulting with Krapf, Hamerton effectively sabotaged the Beke expedition by recommending that the sultan of Zanzibar not give Bialloblotsky letters requesting the assistance of local governors.8

Krapf, who had been at the Rabai mission station since 1843, regularly obtained information about the interior from Arab and Swahili traders. These men often traveled inland along well-established caravan routes to the great East African lakes. Since they dealt in slaves and ivory, they were often vague about their routes and important geographic landmarks. However, over several years of interviewing these traders, Krapf had concluded that there were probably three large lakes in the interior, Nyasa, Tanganyika, and Ukerewe. Despite these conclusions, he reluctantly accepted the erroneous interpretations of a junior missionary colleague, Jacob J. Erhardt, who had arrived at Rabai in 1849. Thirteen years younger than Krapf, Erhardt quickly proved to be a valuable addition to the mission team, especially because he had some medical knowledge. But he soon voiced firm views on a number of issues that were sometimes in conflict with Krapf’s opinions. Krapf and Rebmann also had frictions of their own over the direction of their missionary endeavors, which eventually led to a permanent estrangement. Krapf left Rabai in September 1853, and after a return visit to Abyssinia in 1854, he retired to his native Württemberg.

Meanwhile, Erhardt traveled to Tanga farther down on the East African coast in March 1854. It was his hope to strike inland to the Usambara Mountains, where he planned to establish a mission station. However, the Arab traders along this coast, protective of their slave trading, proved so hostile that Erhardt was unable to travel inland. He finally left Tanga in October 1854 and, after a brief stay at Rabai, permanently departed from East Africa in 1855. Only Rebmann remained at Rabai, where he was to labor for another twenty years before returning to Württemberg a blind and broken man.9

Erhardt’s 1854 stay at Tanga would have lasting consequences for the geographic reputations of all three missionaries. While there, he collected as much information as he could about the interior. From what he heard, it seemed that all caravan routes terminated at great waters to the west. Based on this information, he wrongly concluded that there was an enormous inland sea in the heart of East Africa, and back at Rabai, he easily convinced Rebmann of this as well. Erhardt’s conclusion did not square at all with Krapf’s opinion that there were at least three large interior lakes. Yet Krapf reluctantly acquiesced to Erhardt’s view, perhaps because he did not wish to further exacerbate their very strained relations, and never publicly presented his own correct opinion that there were, in fact, three lakes.

Erhardt called the enormous body of water Lake Uniamesi and drew up a map depicting it at the center of East Africa. He published his map in a Württemberg missionary magazine, Das Calwer Missionblatt, in 1855. Its appearance in such a limited-circulation publication drew little attention. However, the renowned Africa explorer Dr. Heinrich Barth sent the map, along with three letters by Rebmann, to the German geographic scholar August Petermann, who in turn submitted a report on the letters to the widely read Athenaeum, published in London.10 Meanwhile, the CMS sent the map to the Royal Geographical Society, where it was hotly debated at a November 1855 meeting. Its publication in the society’s proceedings early in 1856 caused both an uproar and an outpouring of ink from the pens of the armchair geographers.11

Cooley, MacQueen, and Beke lost no time rushing into print. They wrote passionate letters to the Athenaeum in which they both criticized the map and once again expounded on their long-held theories about the geography of the East African interior.

In the ensuing debates, Erhardt’s creation was pejoratively referred to as the “slug map” because of the peculiar shape given to Lake Uniamesi. It was not only the lake’s shape that drew comment but also the fact that it was said to cover much territory previously thought to be dry. Even Richard Burton, the famous explorer, could not resist throwing critical barbs:

In 1855, Mr. Erhardt, an energetic member of the hapless “Mombas Mission,” had on his return to London offered to explore a vast mass of water, about the size of the Caspian Sea, which, from information of divers “natives,” he had deposited in slug or leech shape in the heart of inter-tropical Africa… thus bringing a second deluge upon sundry provinces and kingdoms thoroughly well known for the last half century.12

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed. Francis Galton of the Royal Geographical Society summed up the then current state of “exceeding ignorance” of the region when he drew attention to the obvious differences between the maps of Cooley, MacQueen, and Erhardt.

The near hysterical debate about the source of the Nile focused the attention of geographers on Lake Uniamesi, and no one took time to comment on a much smaller lake depicted in Erhardt’s map. It lay to the northeast at three degrees north latitude and thirty-nine degrees east longitude in the arid lands of the Rendille and Boran peoples and was called Lake Zamburu. To its southwest was Lake Baringo, and to its east the great Juba (Giuba) River. Except for the longitude, which is off by two degrees, the placement of this lake and the surrounding geographic and ethnographic names leave little doubt but that it is Lake Rudolf. Neither Krapf, Rebmann, nor Erhardt had ever seen Lake Baringo or Lake Rudolf; their information about these distant lakes came from Arab and Swahili traders, who knew of them as good sources of ivory.

Lake Zamburu drew little interest in the swirl of the slug map debate because it was thought to lie well outside the Nile watershed. Almost three decades would go by before that perception would change. By that time, European interest in the Nile and its sources was no longer being driven by the intellectual curiosity of the 1840s and 1850s but by fierce colonial competition for the river. Every possible Nile source became the focus of rival European powers, for whoever possessed the Nile and its sources controlled the heart of Africa and the fate of Egypt.

Erhardt’s map made it clear to the leadership of the Royal Geographical Society that the riddle of the Nile’s watershed could never be deduced either from London or from the East African coast. What was needed was a well-equipped scientific expedition that would make for the interior and accurately replace the fanciful features that had for so long cluttered the map of Africa. They chose for this expedition thirty-five-year-old Captain Richard Francis Burton. He was an officer in the Indian army, a highly respected Arabic scholar, and an experienced traveler who had once made a daring dash into Mecca in disguise. He had proven his mettle under fire, had great leadership abilities, and was fluent in Arabic—a great asset in dealing with the Arab-speaking traders who controlled the East African coast and interior trade routes. But Burton was also domineering, eccentric, opinionated, and intolerant of those who did not measure up to his intellectual standards. It puzzled many that he chose as his traveling companion John Hanning Speke, a rather bland fellow army officer and avid sportsman who had little to show for his ten years in India apart from the usual collection of heads, skulls, and skins. But Burton assessed Speke as the ideal subaltern since he presented an exterior that was modest, quiet, methodical, and self-effacing. What was not so apparent to Burton was Speke’s enormous need to distinguish himself, a need that would eventually transform him from a loyal ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Sources of the Nile

- 2 A Whispered Reality

- 3 A Race Across Maasai Land

- 4 Visitors from Vienna

- 5 An American Approaches from the South

- 6 An American Arrives from the North

- 7 Sportsmen and Ivory Hunters

- 8 Italians at the Source

- 9 Showdown on the Upper Nile

- 10 An Orthodox Partnership

- 11 A Courageous Young Soldier

- 12 Doctor Smith Returns

- 13 Replacing the Union Jacks

- 14 A Lakeside Tragedy

- 15 Dividing the Spoils

- Epilogue

- Chronology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index