- 540 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rangeland Ecology And Management

About this book

The science of range management, like many other resource disciplines, has embraced and integrated environmental concerns in the field, the laboratory, and policy. Rangeland Ecology and Management now brings this integrated approach to the classroom in a thoroughly researched, comprehensive, and readable text. The authors discuss the basics of ran

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rangeland Ecology And Management by Harold Heady,R. Dennis Child in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Grazing Ecology

1

Rangeland Conservation

Rangeland occupies approximately 51 percent (6.7 billion ha) of the earth’s land surface (World Resources Institute 1986). One billion acres (404 million ha) of rangelands, pastures, and woodlands in the United States provide forage and habitat for some 70 million cattle, 20 million deer, 8 million sheep, half a million pronghorn, 400,000 elk, 55,000 wild horses and burros, and many other animals (Evans 1990). All areas produce water and recreational facilities. Rangeland supplies forage for herbivores; additional products such as minerals, construction materials, wildlife, medicines, chemicals, fuel; and intangible values including areas for the preservation of endangered species, anthropological sites, recreational activities, and wilderness. These land-uses as a group are often mentioned as the multiple-uses. Competition and controversy exist over their relative values and coordinated management. The choice among them for the use of public land is as often determined by social preference and judicial-political pressures, as by their economic and physical-biological attributes.

RANGELAND DEFINED

Rangeland is a type of land that supports different vegetation types including shrublands such as deserts and chaparral, grasslands, steppes, woodlands, temporarily treeless areas in forests, and wherever dry, sandy, rocky, saline, or wet soils, and steep topography preclude the growing of commercial farm and timber crops. Rangeland vegetation may be naturally stable or temporarily derived from other types of vegetation, especially following fire, timber harvest, brush clearing, or abandonment from cultivation. Weed and brush control, seeding, and fertilization of rangeland are infrequently applied practices.

The relative importance of different rangeland uses change, giving rise to a second definition that is based on kind of use, usually equated with livestock grazing. Historically, this was the accepted definition. For example, some rangeland is livestock summer range, or another area is deer winter range. Boundaries among the various uses change and many uses are made of the same rangeland. This book does not refer to range or rangeland as a kind of use.

The second definition is the one employed by those with an overriding interest in livestock grazing and by those who are derogatory of livestock grazing, especially on the public lands. Range research and professional practice have fostered this view through concentration on effects of livestock on vegetation and soil and on land treatments aimed at improving livestock production.

The dual definitions have important implications in budgeting, personnel selection and promotions, relationships among user organizations, and cost-effectiveness of land management. The second definition pits the livestock producer against other users; the first considers all the users in coordinated land-use decisions.

RANGE MANAGEMENT DEFINED

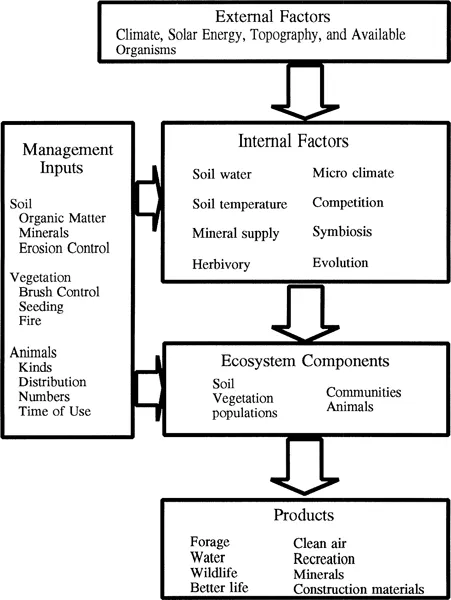

Range management is a discipline and an art that skillfully applies an organized body of knowledge accumulated by range science and practical experience for two purposes: (1) protection, improvement, and continued welfare of the basic resources, which in many situations include soils, vegetation, endangered plants and animals, wilderness, water, and historical sites; and (2) optimum production of goods and services in combinations needed by society (Fig.1-1). The range management profession places emphasis on ecological understanding such as that shown in Figure 1-1 and the following: (adapted from Joyce, 1989)

- Determining suitability of vegetation for multiple-uses

- Designing and implementing vegetation improvements

- Understanding social and economic effects of alternatives

- Controlling range pests and undesirable vegetation

- Determining multiple-use carrying capacities

- Eliminating soil erosion and protecting soil stability

- Reclaiming soil and vegetation on disturbed areas

- Designing and controlling livestock grazing systems

- Coordinating activities with other land resource managers

- Protecting and maintaining environmental quality

- Mediating land-use conflicts

- Furnishing information to policy makers

Management of rangeland requires selection of alternative techniques for optimum production of goods and services with no resource damage. No single set of management practices has ever been found to achieve management goals on rangeland. Ecological principles underlie most of the decisions made by the range manager because of the diversity of natural and humanly disturbed ecosystems.

The use of different management strategies is dependent upon management goals and objectives as well as the ecological potential of the rangeland in question. The planning and application of the many alternatives has come to be known as holistic resource management (Savory 1988). Ideal holistic management requires renewal and sustaining of natural resources, and elimination of destructive use by shortterm mining of vegetation and soil. While emphasis is often placed on effects and management of domestic animals, the overriding goal is rangeland resource rehabilitation, protection, and management for multiple objectives including biological diversity, preservation, and sustainable development for people.

THE RANGELAND ECOSYSTEM

Rangeland systems consist of many interacting environmental forces, local combinations of organisms, and the impacts of use by an increasing number of people. These systems remain primarily under the control of the overall environment, although use and management of rangeland ecosystems alter populations of organisms and change the rate of physical and biological inputs (Fig. 1-1).

Rangeland Development

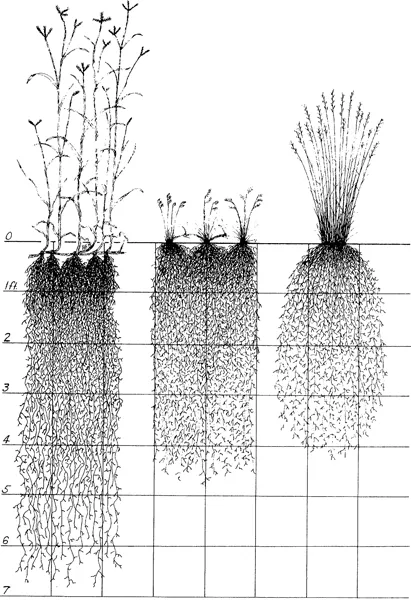

The topmost box in Figure 1-1 depicts the interacting state factors of Jenny (1941). He suggested that soil is a function of parent material, relief, climate, and organisms. Over time, well-developed or mature soils result. Major (1951) applied Jenny’s concept to vegetation and developed the thesis that vegetation depends upon the same state factors as does soil. Primary succession is the development from pioneer to relatively stable communities of plants and animals beginning on raw parent material. Mature soil and climax communities continue to be located at specific topographic places on particular physiographic bases and to receive an energy combination the universe provides for each spot. Jenny (1958) called the wide variation in natural ecosystems landscapes. Other terms that apply to the homogeneous units within landscapes on rangeland are habitat types (Daubenmire 1970), range sites (Dyksterhuis 1949), and ecological sites (Jacoby 1989). Landscape systems are on a complicated spatial scale because each range site or location, even a square decimeter or smaller, has its separate set of organisms, inputs, and responses. These vary continuously through space as well as time. Two examples are shown in Figure 1-2 of rangeland deterioration and improvement.

Rangeland Deterioration

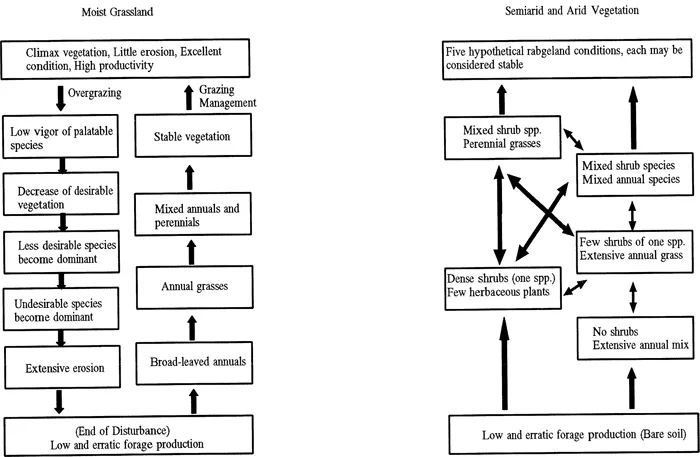

The human rangeland resource user entered this system after it was well developed. Most areas had mature soils and climax vegetation, only temporarily set back because of occasional natural disturbances. The new land-users in the late 1800s and early 1900s destroyed the natural grasslands to make room for food crops, harvested timber for fuel and shelter, and replaced the large wild herbivores with domestic animals. Too many poorly managed animals overgrazed rangelands, causing deterioration of vegetation through several commonly accepted stages (Fig. 1-2). The most palatable plant species were selected first, continually grazed, and closely defoliated; this practice reduced plant vigor, lessened seed production, and eventually, caused plant death. Usually the space vacated by desirable species became the expanded home of less palatable and nutritious species. If overgrazing continued, these species gave way to annual invaders, many of which were weeds introduced from other continents. The palatable species in the pioneer successional stages became rare, and continued overgrazing reduced the invaders. Deteriorated rangelands resulted in ever-widening patches of totally bare soil, beginning where animals naturally congregated. This process of ecosystem destruction occurs worldwide and is one cause of desertification.

Disappearance of soil-holding mulch and plant roots permitted erosion, which further destroyed the land. Accelerated erosion is characteristic of overgrazing. Except on steep slopes and fragile soils, erosion came after considerable vegetational deterioration. In Figure 1-2, deterioration and improvement are shown for a sequence that moves regularly away from and toward stability and another that shows irregular change with various stable combinations of species.

An extensive summary of range problems in the western United States by the United States Forest Service (1936) established the fact that overgrazing had already destroyed more than half of the range forage resources and at that time deterioration was continuing on three-fourths of all rangeland. Little more than 75 years of high livestock numbers, uncontrolled grazing on public lands, and lack of knowledge or care for the land mainly caused the destruction. Overuse of the land was fostered by society and approved by government; it was a benevolent and necessary policy for westward expansion of the United States. In addition, extensive droughts and drastic price fluctuations combined to cause periodic presence of surplus cattle and sheep on the western ranges. Sufficient concern by the 1930s resulted in efforts to regulate livestock grazing on western public rangelands to reduce erosion and rehabilitate the national rangeland resources.

The percentage of rangeland in poor condition decreased from 36 percent to 18 percent from 1936 to 1984 (CAST 1986). During the same period the percentage in good to excellent condition increased from 16 to 36 percent. From 1960 to 1988 numbers of pronghorn, deer, bighorn sheep, elk, and moose have shown dramatic increases on public rangelands in the presence of livestock grazing (Bureau Land Management 1989). Perhaps as much as 60 percent of the Nation’s rangeland is in stable condition. The western rangelands as a whole have a denser cover of vegetation and less erosion in 1990 than they had in 1890. Accomplishments are many but there is still improvement to be made.

Rangeland Improvement

The range manager may begin efforts to halt destructive processes and increase yield at any stage of range condition (Fig. 1-2), because the primary ecosystem is seldom completely destroyed. Secondary plant succession often begins with broad-le...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- PART ONE GRAZING ECOLOGY

- PART TWO GRAZING MANAGEMENT

- PART THREE VEGETATION MANAGEMENT

- PART FOUR MANAGING RANGELAND COMPLEXITY

- Appendix One: Scientific and Common Names of Plants

- Appendix Two: Scientific and Common Names of Animals

- Index

- About the Book and Authors