- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a review of recent development in Africa. It reviews NEPAD and the AU and suggests what must be done for African countries to reverse their growth and security trajectories by asking if any African country will establish the prerequisites for sustained high-level growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of Africa by Jeffrey Herbst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The African Development and Security Record

Numerous excellent studies have documented the economic challenges facing Africa, the profound negative consequences of low growth for Africa’s peoples, and the increasing role that conflict has played in thwarting the continent’s ambitions.1 Rather than provide yet another analysis of the African economic experience, this paper examines three trends which are especially important to understanding Africa’s development experience, the relationship between security and development, and the likely viability of the NEPAD proposals.

The overall record is poor

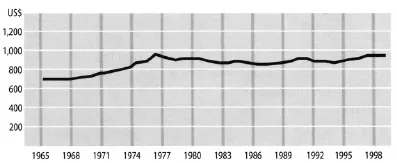

A critical first observation concerns Africa’s poor growth, in absolute and relative terms, particularly since the late 1970s. Per capita growth in the 1960s was positive and, in retrospect, impressive, although it was held at the time to be inadequate. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that African countries, as commodity producers, generally benefited from the sharp upswing in raw-material prices in the 1970s, when the price of oil (an important export for a few African countries) increased dramatically and when the prices of other commodities rose due to the fear that many cartels could develop.

However, when the Shah of Iran was deposed in 1979, the subsequent further dramatic increase in the price of oil had an overall harmful effect on Africa. Soon thereafter, the price of oil itself began to decline, along with other commodity prices. At the same time, poor economic policies adopted shortly after independence were beginning to have a profound impact on a number of countries. It was becoming obvious that many economies had ‘hollowed out’, as investors slowly opted to flee.

Graph 1 GDP Per Capita in Sub-Saharan Africa (constant 1995 US$)

Source: World Bank, World Bank Africa Database 2002 on cd-rom (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2002).

As a result, beginning in the mid-1980s, prompted by the imposition of increasing conditions by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, many African countries embarked on a halting programme of economic reform, encompassing, for instance, devaluation of grossly overvalued currencies, reduction of government deficits, reform of parastatals, and changes in the way that farmers were paid. While these reforms were necessary, it soon became apparent that they were often not credible and did not go far enough because of poor governance in many countries. Therefore, subsequent reform efforts, often impelled by conditions attached to bilateral and multilateral assistance, focused on increasing the independence of central banks, reforming the civil service to make it smaller and more efficient, improving judicial systems so that countries could protect property rights, reforming the police so that they could fight crime, and improving the allocation of social services to take account, especially, of the critical role of women in development. Finally, the wave of political liberalisation that swept across Africa from the early 1990s also raised fundamental questions about democracy, voting rules, self-determination of minority groups and human rights.

Consequently, since the early 1980s, African countries have been involved in a series of debates that have questioned, at one time or another, almost every internal practice and policy of the state. Given how difficult and controversial many of these reforms have been, implementation has been a faltering and extremely uneven process. A continental scorecard would show that there has been some improvement in macroeconomic performance (especially the elimination of overvalued exchange rates), less success on the more difficult issues of improving governance, and slow progress on democratisation. Of course, two decades is hardly a long time given the ambitious nature of the reform proposals; however, Africa’s desperate economic situation makes the reforms urgent.

There was, in fact, a brief growth spurt in the early 1990s, propelled by the devaluation of the CFA franc and other policy reforms. However, the wars that engulfed much of Africa in the late 1990s (notably in Angola, the DRC, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Sudan) erased the fragile gains of the previous few years. Hence, despite many policy initiatives in the 1980s and 1990s, Africa as a whole has never managed to return to the (relative) high point of the late 1970s.

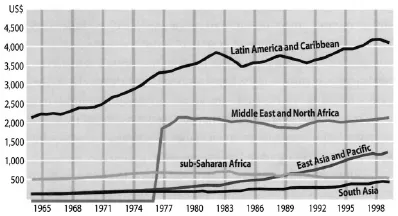

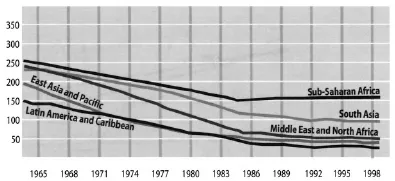

Africa’s disappointing performance in comparison to other regions is evident from the chart below. The Middle East and North Africa, and East Asia and the Pacific – both of which were poorer than Africa in the early 1960s – have exceeded it in relation to absolute per capita.

South Asia, a region that was significantly poorer than Africa in the early 1960s, has now almost caught up and probably will surpass Africa given its distinct positive trajectory. More generally, questions posited about African development are increasingly different to those asked about other regions. During meetings of leaders of East Asia or Latin America, development debates centre on attracting foreign investors and making local industry more competitive. For a large number of African countries, basic development questions now revolve around institutional survival rather than success in the new global economy.

Graph 2 GDP Per Capita Over Time (constant 1995 US$)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2001 on cd-rom (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2001).

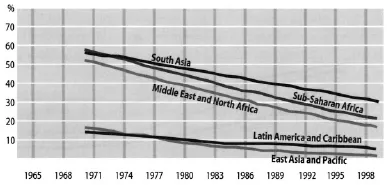

Graph 3 Illiteracy Rate (percent)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2001.

As is by now well known, all of Africa’s development indicators reflect its poor economic performance. There has, of course, been some progress in African development over the past four decades. But the victories have been hard won and the achievements are often frail, not as impressive as in other developing countries, and, given the overall environment of profound scarcity and conflict, always vulnerable to reversal. Indeed, one of the worst effects of the HIV/AIDS crisis is that the pandemic hit Africa just as some countries were beginning to introduce substantial economic and, in some cases, political reforms. In some states, the virus that causes AIDS may erase any gains from public health improvements introduced since independence. Thus, just when Africa might have expected a burst of economic and political creativity in response to the freedoms achieved in the 1990s, it is instead contending with the fact that one of the most brutal pandemics in human history is killing off many of its most skilled citizens.

Child mortality rates are also increasing in Africa, and, in some countries, people are only expected to live until their mid-40S.

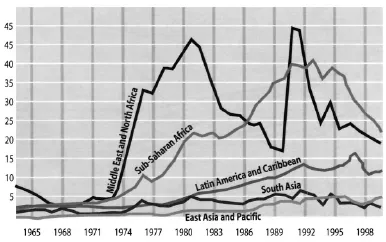

Africa’s growth record is particularly disappointing in view of the extremely generous level of foreign assistance that it has been awarded. As the chart on Aid per Capita (page 16) makes clear, the international community never abandoned Africa; indeed, what is most striking is the willingness of Western countries to keep pouring money into Africa even though it was obvious that it was having little effect. As Nic van de Walle has noted, Africa is already the target of a Marshall Plan. At the height of the original Marshall Plan (after the Second World War), aid accounted for 2.5% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of countries such as France and Germany. In contrast, in 1996, Africa, excluding Nigeria and South Africa received, on average, aid that was the equivalent of 12.3% of GDP.2 In Mozambique, for example, in 1997, the gross national product (GNP): aid ratio was 43%; in Sao Tomé and Principe 117%; in Guinea-Bissau 71%; and in Rwanda 49%.3

Graph 4 Mortality Rate for Children Under 5 (deaths per 1,000)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2001.

It is one of the great disappointments of the post-Second World War era that foreign aid has not produced better results. Certainly, if a domestic policy had a similar record of failure in any industrialised country, it would have been curtailed many years ago. We now understand that foreign aid can be part of a country’s development success but only if that country is committed to development (as opposed, say, to using all available resources to promote the political fortunes of its leadership) and if basic governance is good enough to enable the money to be used effectively.

Leaders who are not dedicated to development can divert aid and circumvent the will of donors in countless ways. Donors may demand that their money be used effectively, but, if a country does not have the necessary commitment and governance structures in place, it will be wasted. Of course, many donors have not always prioritised development. Much foreign aid has been given for strategic reasons and due to historical ties (especially between European countries and their former colonies), rather than because of clear economic assessments of who will use the money best. Conditionalities have varied from being over-extensive to scarcely applied, and nearly always predicated as much on the domestic political needs of the donor as on the longer-term requirements of the target state. The utility of foreign aid is also blunted when Western countries use it to hire their own consultants or to demand that purchases be made from their own suppliers. Past experience and recent commitments in turn raise questions not only about the focus of aid but also about the role and extent of conditionality and the wider relationship between the donor and the recipient nation.

Graph 5 Aid Per Capita (constant US$)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2001.

Growing heterogeneity

The second important observation to note when examining Africa is the continent’s heterogeneity. When the focus shifts from the regional to the country level, it becomes obvious that Africa’s growth record is increasingly varied. Some African countries have become significantly richer and others considerably poorer in the post-independence period. The uneven effect of conflict only served to accentuate differences in growth performance. In particular, some of the countries that have done particularly poorly (Liberia, Sierra Leone and Somalia, for instance) have experienced a decade or more of war and have a government in name only, if that. In contrast, those relatively few states that have done well (Botswana and Mauritius, for example) are increasingly asking questions that are fundamentally different from those that occupy the rest of Africa. Mauritius, for instance, is working to reorient economic activity on the island away from the textile industry and towards information technology, which will put it in a position to become a rich country in the twenty-first century. By contrast, many other African nations would be delighted to have a textile industry or, at this point, to have a profitable raw-material sector.

It is important to note that extrapolation in regard to one or even a group of countries must be carried out with caution, given that the sample may not be representative of an increasingly divergent whole. Neither the occasional success nor dismal failure may mean much on a continent where the contrast between the extremes is becoming ever greater.

Size counts

In fact, when examined closely, it becomes obvious that the third great trend affecting African economic performance is the exceptionally poor performance of large countries, which have suffered from conflicts related to their diverse ethnic composition. While the DRC (50m people), Ethiopia (63m) and Nigeria (124m) together account for 37% of Africa’s total population, they have particularly disappointing development records.

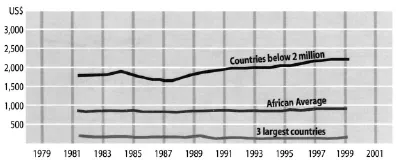

Graph 6 GDP Per Capita by Population Grouping (constant 1995 US$)

Source: World Bank, World Bank Africa Database 2002.

As the chart shows, since 1981 (the first year there is data on Ethiopia), the three African giants have achieved considerably lower rates of per capita income than the African average (their per capita income rates declined by 18% compared to the African average, which increased by 7%). In contrast, the 13 countries with populations below two million4 enjoyed higher per capita income and grew by 21% between 1981 and 1999. The problem, of course, is that these 13 states account for only 1.7% of Africa’s population. Indeed, the fundamental problem affecting Africa is that, overall, the countries that have performed worse than average are those that are extremely large and populous.

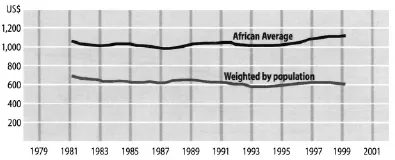

When ‘average’ continental per capita income is calculated, the income of Mauritius ($4,120 per person in 1999, but with a population of only 1.2m) amounts to the same as Ethiopia ($112, but with a population of 63m). The following chart contrasts ‘average’ continental per capita income with the same figure weighted by population. The latter is essentially what the ‘average’ African received between 1981 and 1999. As the chart suggests, the experience of the ‘average’ person is even worse than is suggested by simple continental statistics because the countries with the largest populations have been doing much worse than even the African average.

As a result, one of the underlying problems that African countries appear to face is that of diseconomies of scale. Indeed, it seems more difficult for states to institute good governance procedures in larger countries. The Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) has created an Economic Sustainability Index that aggregates 36 measures of ‘sustained growth, human capital development, structural diversification, transaction costs, external dependence, and macro-economic stability’. Each country earns a score of between one (low sustainability) and ten (high sustainability).5 The ECA concludes that: ‘The Economic Sustainability Index is uniformly low across the region’.6

Graph 7 GDP Per Capita (constant 1995 US$)

Source: World Bank, World Bank Africa Data base 2002.

However, it is interesting to examine the countries that are doing relatively well or badly. The best performers include the Seychelles, Tunisia, Egypt, South Africa, Mauritius, Morocco, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Algeria. Of those, four are in North Africa. Of the six Sub-Saharan countries, five have populations of less than two million. South Africa is the only one that is not small and that has received a relatively high economic sustainability score. In contrast, the ten worst performers (Sierra Leone, Chad, Niger, Guinea-Bissau, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Uganda, Ethiopia, Mali, and the DRC) include two of the three most populous countries in Africa.

The chronic problem facing the DRC, Ethiopia and Nigeria has been that ethnic divisions have been serious enough to prompt civil war in all three states and, even during peacetime, to force leaders to devote huge resources to patronage in order to try to keep their countries together. Consequently, governance has been especially poor in these three states, which are home to one-third of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, Angola and Sudan, two other countries that should have been drivers of African growth because of their size and resource endowments, have instead experienced long periods of conflict. Neither state has...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction Western Concerns and African Initiatives

- Chapter 1 The African Development and Security Record

- Chapter 2 Western Responses to Africa's Crisis

- Chapter 3 Paradox and Parallax: The Special Case of South Africa?

- Chapter 4 NEPAD and the AU: Towards a New Order?

- Chapter 5 Tasks for the Future

- Conclusion Zeitgeist and Realism

- Notes