- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The International Conference on Elvis Presley, convened at the University of Mississippi in August, transformed a rock and roll icon into a scholarly phenomenon. Educators, artists, and Elvis aficionados from across the worldplus over one hundred internationally based reporterscollected on Oxford, Mississippi, soil to analyze and celebrate Elvis impact on the world stage.From this conference, which became front page New York Times Magazine news, springs this book, the best and brightest essays and artwork swirling around the cultural, social, political, and iconographic figure of Elvis Presley. Discussed within are such topics as Elvis as Southerner, Elvis as sign system, Elvis multicultural audiences, Elvis and rockabilly, Elvis as redneck, the Elvis oeuvre, and Elvis religious roots. Taken together, In Search of Elvis represents a daring and groundbreaking academic analysis. Richly illustrated with original Elvis-inspired artwork, this book captures the subterranean essence of one of the most phenomenal artists to have ever lived. }The International Conference on Elvis Presley, convened at the University of Mississippi in August, transformed a rock and roll icon into a scholarly phenomenon. Educators, artists, and Elvis aficionados from across the worldplus over one hundred internationally based reporterscollected on Oxford, Mississippi, soil to analyze and celebrate Elvis impact on the world stage.From this conference, which became front page New York Times Magazine news, springs this book, the best and brightest essays and artwork swirling around the cultural, social, political, and iconographic figure of Elvis Presley. Discussed within are such topics as Elvis as Southerner, Elvis as sign system, Elvis multicultural audiences, Elvis and rockabilly, Elvis as redneck, the Elvis oeuvre, and Elvis religious roots. Taken together, In Search of Elvis represents a daring and groundbreaking academic analysis. Richly illustrated with original Elvis-inspired artwork, this book captures the subterranean essence of one of the most phenomenal artists to have ever lived.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In Search Of Elvis by Vernon Chadwick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Music

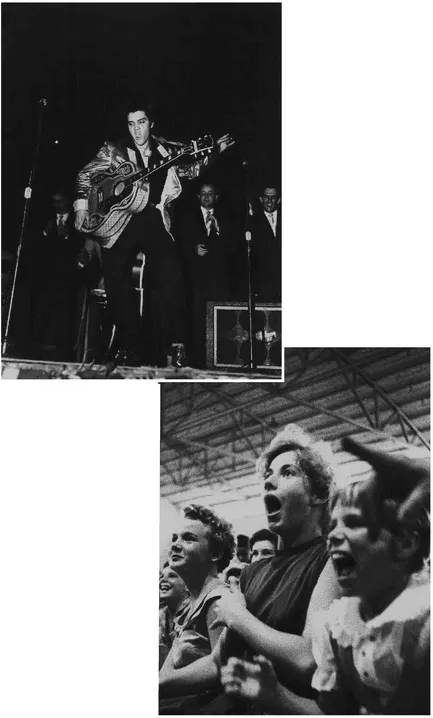

The Hillbilly Cat. Love Me Tender, 1956. Collection of Ger Rijff.

1 Country Elvis

BILL MALONE

Sometime in late 1955, during my second year as a student at the University of Texas, I attended a country music concert at the old municipal auditorium on the southern edge of Austin. I went to see my current musical hero, Hank Snow, and was bitterly disappointed when his portion of the show was cut short in order to bring out the evening's headliner, and to make way for a hastily scheduled second show, I do not know now which shocked me most, the physical gyrations of the young singer who dominated the stage that afternoon, or the screaming response of the young women who rushed the stage. After all, neither singer nor audience were acting like they were supposed to act— male country singers did not permit physical mannerisms to overwhelm or detract from the lyrics of a song, and neither they, nor country women, were permitted to exhibit sensual feelings in public.

I have long thought that, unlike many others who have given almost religious testimonies,1 I clearly was not transformed by the experience of seeing Elvis Presley perform for the first time. My passion for music was strong, and as the product of a southern, poor-white, Pentecostal home, I shared a history of social and cultural experiences with Elvis far closer than most of my contemporaries who were swept away by his music. If anything, my search for traditional forms of country music became more intense, especially after 1957 when the rockabilly surge began to reach its peak. Bluegrass music, for example, became a refuge for me and many other "traditionalists" who saw the old styles of music disappearing from the radio and jukebox.

In retrospect, although I did not take up the guitar and become a rockabilly, Elvis's Austin concert did serve as a kind of transforming experience. For me, it was a barometer marking both the beginning of a revolution in American music and my own loss of innocence. I actually had become familiar with Elvis earlier, in the summer of 1954 when his first Sun releases were played on Tom Perryman's radio disc jockey show out of Gladewater, only thirty miles or so from my home in Tyler. I probably sensed then, well before the Austin concert, that the stirrings of a musical revolution were under way, and that southern boys and girls were already ripe for transformation. Rhythm-and-blues songs had begun to dominate the jukebox in the student center at Tyler Junior College before Elvis's first records were released, and my classmates had already discovered the joys of "Dirty Bop" and the suggestive lyrics of such songs as "Fever" and "Work with Me Annie." Nevertheless, until that afternoon in Austin, when the upstart Elvis upstaged the veteran Hank Snow, the physical dimensions of the musical change had not been clearly displayed to me, nor had I actually witnessed the stirrings of feminine revolt, as young women tentatively recognized and openly displayed their own sexual feelings.

Country music had seemed economically strong and stylistically pure in 1954, and had dramatically fulfilled the prophecy made in 1944 by the entertainment trade journal Billboard, which asserted that after the war was over, country music would be the "field to watch."2 Powerful radio stations transmitted the music to all parts of the nation, and scores of smaller ones played both live country acts and country records periodically during their broadcasting hours. An estimated 400,000 jukeboxes contributed mightily to the burgeoning of a rejuvenated recording industry, and approximately 600 record labels introduced the nation's grassroots styles to a public that was eager to savor the prosperity that had been denied to them during the war.3

The man who had stood at the center of country music's postwar surge, Hank Williams, had died in 1953, but his records still played often on local radio and jukeboxes. While traditional sounds prevailed in the music of people like Hank Snow, Kitty Wells, and Webb Pierce, one could even hear some really old-timey sounds in the music of such entertainers as Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, and the Louvin Brothers. Country disc jockeys still affected hayseed sounds and demeanors, and they actually played records requested by listeners. Furthermore, when a record started to play, the faithful country music fan could tell who the singer was, because Lefty, Hank, Kitty, and the others used their own musicians on recording sessions. Although stylistic differences certainly existed among country musicians, and terms like "bluegrass" and "western swing" were beginning to be attached to country subgenres by the middle of the fifties, most fans made no distinctions and could easily bestow their affections upon performers who were radically different from each other. All of the substylings seemed grounded in grassroots tradition, and most spoke with a southern accent.

I do not know now which shocked me most, the physical gyrations of the young singer who dominated the stage that afternoon, or the screaming response of the young women who rushed the stage. Collection of Ger Rijff.

The social demographics of the era, however, tell a more interesting story. And they explain both the expansion of country music and other grassroots forms, as well as the emergence of Elvis and the Youth Culture that nourished him and the rockabilly phenomenon. Although the contours of change were already present in the rural South before the coming of the great conflict, World War II unleashed a social revolution in the region. Massive population shifts within the South, from agriculture to industry and from farms to cities, and to cities in the industrial Midwest and on the West Coast, promoted economic improvement, altered lifestyles, and new attitudes. Change, though, did not occur instantly, and the habits and assumptions of the rural past receded slowly. Millions of rural southerners changed their residences and occupations, but they found that folkways, values, or expectations could not change as rapidly. Most people approached the postwar period with hope and measured optimism,4 but they remained cautious about the future. This sense of caution was apparent among our older brothers and sisters who had fought the war, and among my generation, which was born amid the scarcity of the Great Depression. Scarcity, though, slowly gave way to abundance, and our nieces and nephews—the famous baby boomers—grew up in an atmosphere of boundless expectations.5

For those of us who grew up in working-class households, our parents still thought in terms of limits and perceived the world through a fatalistic lens. They reminded us often of the Great Depression, and warned that another might surely come. Talk of a third world war was not uncommon during the early years of the Cold War, and the presence of the Atomic Bomb meant that such a conflict would be catastrophic (unless, of course, the United States made a preemptive strike on the Soviet Union).

With a folk wisdom born of experience and nourished by tradition, they told us to be cautious in our choices and not to expect too much from life. I will never forget what my father said to me when he left me off at Tyler Junior College on the first day of freshman registration in 1952: "Don't sign up for anything big like lawyer." And, at first, we were cautious. The Consumer Society did not immediately seduce us, but with its promises of clothes, cars, sexual fulfillment, and culture—pop culture—it gradually built a loyal and passionately committed following among the young people of the nation.

While postwar society might be more economically secure, few people before 1954 questioned the assumption that the traditional and "comfortable" hierarchy of relationships among men and women, blacks and whites, and young and old would be preserved.6 Few of us realized just how strongly those relationships had been undermined by the war. Displaced country people responded to postwar society in a variety of ways, and with varying degrees of receptivity to urban life. In a world still marked by economic flux and shifting gender relationships, most men clung to the vision of patriarchal authority.7 Many of them sought the comradeship of other men in situations that reaffirmed their masculine dominance. For some men (and an increasing number of women), the honky-tonk provided diversion and escape. In this institution that both eased and mirrored the transition from country to urban life, country music was being preserved and redefined.8

Although the honky-tonk won the allegiance of many displaced rural folk, it could not sever the cherished link that many of them maintained with the church. Even the honky-tonk singers, and their audiences, found it difficult to forget or ignore the moral injunctions generated by religious instruction. Consequently, honky-tonk songs were often laced with the themes of guilt and moral ambiguity. The "old-time religion" did bring sustenance to rural folk who were trying to preserve identity and make sense of the sometimes bewildering changes wrought by urban life, but the older forms of faith were changing just as subtly as the people who subscribed to them. As religion moved to town, initially into store-front churches, the tents of the charismatic healing evangelists, or the broadcasts of the radio evangelists, it changed in subtle ways.9 It waged war with the world while simultaneously embracing many of its innovations—sophisticated advertising, radio, sound recording, and television. As wealth became more available to working-class southerners, the church's response to prosperity became increasingly ambivalent. Visions of "little log cabins" tucked away in "the corner of Glory Land" gradually gave way to promises of mansions in Heaven and here on earth.10 Gospel music, the musical offspring of southern evangelical Christianity, exhibited a similar fusion of otherworldly concern and contemporary awareness. Most dramatically represented by the quartets that had originally emerged from the shape-note singing school tradition, gospel music experienced accelerated growth in the decade after World War II. Appearing often on radio broadcasts and at well-publicized all-night singings, the high-powered gospel quartets enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with country music, and their performances were readily available to southerners of all age groups.11

Radio, jukeboxes, the movies, the automobile, and television brought the nation's popular culture into the lives of all southern working people. Not only did these innovations integrate working folk more firmly into the socioeconomic processes of the nation, they also contributed to the making of a self-conscious youth culture. Like young people elsewhere in the nation, southern youth experienced the moods of confusion and uncertainty that gave rise to the famous "rebels without a cause." But southern working-class youths were undergoing additional stresses. Sharing uncertain economic futures, torn between the values of their parents and those promoted by popular culture, Elvis and his blue-collar generation were at once hostile to and envious of middle-class culture. Shut out of the mainstream, they nevertheless longed to enter it. On most levels, then, they were not rebelling at all.

Elvis and his generation were the first southerners to be so strongly molded by popular culture. Like most youth of his era, he was part of everything he heard. Well before his family moved to Memphis in 1948, he had begun to absorb a wide variety of musical sounds in his hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi. But in the big city, with its movies, radio stations, television, automobiles, and more readily available wealth, Elvis was presented with a smorgasbord of influences. Every form of southern music was available to him—the country music loved by his parents; the newer bluegrass style that thrilled him with its energy and speed; gospel music, above all, with its flamboyant singers who dressed smartly and sang with incredible power and vocal range; and rhythm and blues, which was attracting white youth everywhere with its freedom and spontaneity. Mainstream pop music, which sometimes borrowed from these forms, was, of course, constantly available too. And it is no wonder that Elvis admired people like Dean Martin and Perry Como, because they enjoyed a prestige far beyond that of grassroots musicians, and were dominant on the major television shows of the day (country musicians, in contrast, were still sitting on hay bales in the television series that featured them).12

By 1954 none of the southern grassroots musical forms were totally distinct from each other, and each had changed in certain ways as their performing contexts became more urban and national. Country, rhythm and blues, gospel, Cajun, and other "rural" southern styles, in fact, drew their vitality and strength from their contacts with the cities. Hundreds of small record labels introduced grassroots musical styles to America after the war, and, in a few cases, recording entrepreneurs consciously tried to fuse the styles of black and white performers. A few "racial liberals," in fact, like Sydney Nathan of King Records in Cincinnati and Sam Phillips of Sun Records in Memphis, tried to break down racial barriers by making black music available to white youth. We are generally aware of the "covers" of black music being made in the early fifties by such white singers as Pat Boone and Georgia Gibbs, but we need to be reminded that white country musicians had been borrowing from black sources since the beginnings of their music's commercialization in the 1920s.13 Such singers as Jimmy Tarlton, Dick Justice, Frank Hutchison, and, of course, Jimmie Rodgers recorded black-derived material in the twenties, while in the 1930s Cliff Carlisle, Jimmie Davis (who even made some early recordings with black musicians), Buddy Jones, the Allen Brothers, Gene Autry, Milton Brown, and Bob Wills dipped often into the recorded Afro-American songbag.14 More immediately in his own youth, in the forties and early fifties, Elvis would have heard the covers of black material, both religious and secular, performed by such singers as the Delmore Brothers, Red Foley, Molly O'Day, Martha Carson, the Maddox Brothers and Rose, Hardrock Gunter, Bill Haley, and Hank Williams. The country boogie craze of that era exhibited its influence directly in the lead guitar playing and antic, slapped-bass styles of Elvis's first accompanying musicians, Scotty Moore and Bill Black.

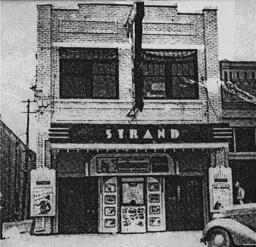

Elvis and his generation were the first southerners to be so strongly molded by popular culture.

Courtesy of Tupelo Museum.

Courtesy of Tupelo Museum.

Country musicians had always been fascinated with black rhythms and inflections, as had their "folk" forebears before them. Beginning as early as the ubiquitous black fiddlers, juba dancers, and spiritual singers of the nineteenth-century South, and extending through the early-twentieth-century emergence of ragtime pianists and blues performers, African-Americans had offered white musicians a means of getting off the beat, syncopating it, sliding notes together, and otherwise experimenting with rhythms in ways that had not been emphasized in European-derived styles.15 Above all, they provided a musical forum for challenging old orthodoxies, rebelling against inherited standards, and shocking people—presenting a way of being naughty and yet still conveying the feeling that someone else's culture was being utilized. Black culture was presumed to be hedonistic, and the white person who sampled it (whether he be Jimmie Davis, Gene Autry, or Elvis Presley) could always go back to his own, safe way of life after the experimentation.

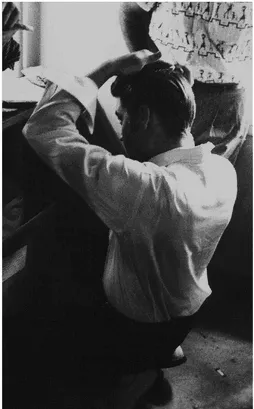

He found a way to distinguish himself in the hairstyles of the method actors, and in the loud and flamboyant clothing merchandized by Lansky Brothers on Beale Street.

Collection of Ger Rijff.

Collection of Ger Rijff.

Elvis's experiments with black music, then, had abundant precedents in the white country tradition. He was even preceded in the 1950s by Bill Haley, of "Shake, Rattle, and Roll" fame, who also toured with Hank Snow several months before Elvis teamed with the great country singer. No one in his right mind, though, would argue that Elvis and Haley were comparable in their treatment of black material or that Elvis was just one more country singer dipping into the Afro-American musical tradition. Elvis was indeed different, and the difference lay in the style of presentation. His country predecessors had performed material that was often sexier than that performed by Elvis; there is nothing in his repertoire, for example, comparable to Cliff Carlisle's "Tom Cat and Pussy Blues," Jimmie Davis's "Red Night Gown Blues," or the Light Crust Doughboys'...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Ole Massa's Dead, Long Live the King of Rock 'n' Roll

- PART ONE MUSIC

- PART TWO RACE

- PART THREE ART

- PART FOUR RELIGION

- PART FIVE EPILOGUE

- Notes

- About the Editor and Contributors

- Index