eBook - ePub

Consuming Behaviours

Identity, Politics and Pleasure in Twentieth-Century Britain

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Consuming Behaviours

Identity, Politics and Pleasure in Twentieth-Century Britain

About this book

In twentieth-century Britain, consumerism increasingly defined and redefined individual and social identities. New types of consumers emerged: the idealized working-class consumer, the African consumer and the teenager challenged the prominent position of the middle and upper-class female shopper. Linking politics and pleasure, Consuming Behaviours explores how individual consumers and groups reacted to changes in marketing, government control, popular leisure and the availability of consumer goods.From football to male fashion, tea to savings banks, leading scholars consider a wide range of products, ideas and services and how these were marketed to the British public through periods of imperial decline, economic instability, war, austerity and prosperity. The development of mass consumer society in Britain is examined in relation to the growing cultural hegemony and economic power of the United States, offering comparisons between British consumption patterns and those of other nations.Bridging the divide between historical and cultural studies approaches, Consuming Behaviours discusses what makes British consumer culture distinctive, while acknowledging how these consumer identities are inextricably a product of both Britain's domestic history and its relationship with its Empire, with Europe and with the United States.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Consuming Behaviours by Erika Rappaport,Sandra Trudgen Dawson,Mark J. Crowley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Economic Conditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

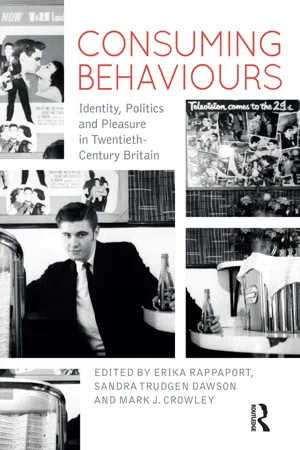

Writing in 1941, as Great Britain was under its greatest threat, George Orwell mused: ‘We are a nation of flower-lovers, but also a nation of stamp-collectors, pigeon fanciers, amateur carpenters, coupon-snippers, darts-players, crossword-puzzle fanciers.’ A harsh critic of fascist propaganda and mass commercialism, Orwell continued, ‘[a]ll the culture that is most truly native centres round things which even when they are communal are not official – the pub, the football match, the back garden, the fireside and the ‘nice cup of tea’.1 Orwell celebrated an Englishness defined by pleasures that he imagined were apolitical and outside of the marketplace. Similarly, Richard Hoggart, literary critic and founding scholar of British cultural studies, recalled an interwar working-class generation not yet ‘assault[ed]’ by the ‘mass Press’, ‘wireless and television’ and the ‘ubiquitous cinema’; or, as he famously put it, the unreal ‘candy-floss’ world of 1950s mass culture.2 Many casual observers and scholars likewise assumed that mass consumer society wasn’t quite British, and that it arrived via young people who since the late 1950s had embraced unbridled consumerism. Hoggart, for example, described how ‘middle-aged working-class’ couples’ homes were still ‘Edwardian’ with ‘living-rooms little changed from the time they equipped them or took them over from their parents,’ while ‘young couples like to go out and buy everything new’.3 Despite a great deal of scholarship challenging Hoggart and Orwell’s account of modern Britain, it has remained a very persuasive narrative.4 Our choice for the cover of this book might at first glance appear to reinforce the understanding of consumer culture as a foreign, ‘American’ army colonizing Britain’s youth in the 1950s.5 However, the essays in this volume were chosen to complicate this account and open up new questions for further research.

The cover photo is a posed portrait of Vince Taylor taken by Rick Hardy in 1958. Both sitter and photographer were part of the early British rock music world and both influenced a number of genres, including skiffle, rockabilly, glam rock and punk. The photo was taken when Hardy was in his 20s and Taylor was 19 in the 2 I’s, the Soho coffee bar in Old Compton Street, which was a nursery for British rock ‘n’ roll and a conduit of American and European cultural influences. The coffee bar and its neigh-bourhood were at this time associated with a rebellious foreign masculine hetero- and homosexual consumer culture.6 This setting and Taylor’s clothing, hairstyle, sideburns and his casual yet aggressive and sexy posture provide a veritable catalogue of the new mass commodities, cultural forms and technologies which emerged in the twentieth century, many of which we explore in this volume. Taylor is holding a bottle of soda (though it is not Coca-Cola) on top of a Formica table, next to a gleaming chrome Gaggia espresso machine imported from Italy. He sits behind a jukebox that played American music, in front of a poster for Elvis Presley’s new film King Creole, which was currently playing at the Odeon Theatre in Marble Arch. Next to the poster is a collage of photographs with a caption that reads: ‘Television comes to the 2 I’s’. Like the photographs that Penny Tinkler analyses in this volume, this portrait is a work of self-creation in which Taylor and Hardy used photography and specifically chosen props and setting to promote themselves as trend-setters of a new youth-oriented community. They were astute readers of the material world, much like Orwell and Hoggart.

Taylor, significantly, had a transatlantic biography. He was born Brian Maurice Holden in Isleworth, Middlesex in July 1939, but when he was seven his family emigrated to the US, first settling in New Jersey. After his sister Sheila married Joseph Barbera of Hanna-Barbera studios, the family moved to Los Angeles, where Brian attended Hollywood High School. Hanna-Barbera produced some feature films, but it was known for animation, especially the iconic children’s cartoons from the 1960s and 1970s, including the Flintstones, the Jetsons, Yogi Bear, Josie and the Pussy Cats, and many others. Barbera also in a sense produced the figure of Vince Taylor. He became Holden’s manager and brought him to London, where, like his more famous counterpart Tommy Steele, Taylor began his career by covering Elvis Presley songs and copying his gestures, music and clothing style. Although Taylor had a rocky relationship with his band ‘The Playboys’, he became quite popular, especially in Europe. His successes and failures influenced others. The Clash, for example, made Taylor’s 1958 song ‘Brand New Cadillac’ even more famous when they covered it on their album London Calling in 1979. Taylor’s erratic drug-induced behaviour inspired David Bowie’s persona Ziggy Stardust.7 In many respects, then, Taylor and his portrait appear to be perfect examples of mass culture as a drug and as something ‘alien’ to traditional notions of Britishness. This volume suggests otherwise by charting the domestic and international histories that made careers such as Taylor’s possible. We argue that although Vince Taylor, George Orwell and Richard Hoggart disagreed about the implications of mass consumer culture, they all saw this world as a contested arena in which the histories of identity, politics and pleasure came together.

Taylor’s persona was at once a local creation born within particular urban, commercial and leisure spaces and a part of broader transnational networks and cultures that stretched across the Atlantic, English Channel and the Empire.8 Taylor and his friends, family and colleagues were living in a new world in which the things one chose to purchase, use, think and write about and the clothing, food, shelter, social services and leisure one enjoyed increasingly came to define individual and social identities. Marketers, advertisers, corporations, political parties, voluntary and state agencies relentlessly tried to cultivate and control the consumer behaviours of men and women in the UK and its Empire. This tension between promotion and containment provides the common thread linking each of the essays in this volume. Each author examines how products, ideas and services were marketed to and understood by the British public during periods of economic instability, war, imperial crisis and decline, ‘affluence’ and the apparent growing cultural and economic hegemony of the USA.

Defining consumption, consumerism, or consumer society at any period is not easy, but in the twentieth century the advent of mass politics and availability of so many new goods, media and services makes this task even more complicated.9 As many scholars have argued, commodities, the consumer and consumer culture are never constant constructs. The importance and ‘value’ attached to purchases, the use and display of merchandise and leisure do not carry equivalent importance. We agree with Frank Trentmann who has argued that the consumer is a historical category that needs to be interrogated and not assumed.10 Consumption is a historical process that arises out of a shifting and often unbalanced relationship between producer, packager, purchaser and a host of intermediaries. However, we have used the idea of consumer behaviour instead of consumption or consumer society to highlight the similarities between past and present and a range of political, social, cultural and economic activities that revolve around the marketplace but do not necessarily involve purchasing. This is especially appropriate, we believe, during times of rationing, scarcity and economic crisis. It also allows us to examine the significance of women’s market activities in the African Empire that Bianca Murillo shows simultaneously could be defined as buying, selling and market research.

This volume builds upon the insights and methodologies provided by a rich scholarship that already exists on commercial and consumer practices. Some of the contributors draw upon the work of anthropologists, particularly Daniel Miller and Arjun Appadurai, who suggested that commodities have unique histories or biographies in which they shift in and out of commodity status.11 Others return to some of the conclusions that John Benson offered in The Rise of Consumer Society in Britain, 1880–1980. In that seminal volume, Benson focused on organized sports, tourism and shopping to explore whether consumer culture emancipated women, consolidated national identity and created youth cultures that challenged class tensions.12 Several of the authors have also been influenced by cultural theorists such as Dick Hebdige who charted the emergence of youth subcultures revolving around music, fashion and other ‘alternative’ consumer practices and yet also argued that the ‘subcultural response’ is neither simply affirmation nor refusal, neither ‘commercial exploitation’ nor ‘genuine revolt’.13

We are equally indebted to many historical studies of early modern and Victorian consumer cultures. We recognize qualitative and quantitative differences between the 1760s, 1860s, 1930s and the 1960s, but this volume also foregrounds a number of continuities. The very fact that figures such as Vince Taylor believed they were destroying Victorian conceptions of the body, the self, the community, the nation and the marketplace illuminates the importance of this earlier history and suggests the postwar generation believed their parents still lived within the constraints of the Victorian era. Taylor’s revolt was in part directed at nineteenth-century social, religious and political movements and ideologies that had set the terms of debate about how the material world impacted ideas about citizenship, the body, identity and community. Political economy, political reform, evangelicalism, imperialism and class, gender and racial ideologies informed ideas about commodities, spaces and consumer behaviours. Numerous political and social reform movements used the idea of the consumer as a citizen to effect change, but they also circumscribed many forms of consumption. The American revolutionaries, British abolitionists, temperance reformers, co-operators, free traders, tariff reformers, suffragists and anti-colonial nationalists disagreed about what constituted productive consumer behaviours, but they all envisioned consumers as political actors.14 For example, the liberal-oriented evangelical temperance movement of the 1830s and 1840s developed a vision of the productive and moral consumer when it tried to restrain drinking among unruly, young working-class men. Like the reformers that Brett Bebber and Kate Bradley look at in this volume, the temperance community attempted to channel desires towards what they viewed as moral and profitable ends. As one Irish campaigner explained in 1840, sobriety would shift scarce funds from drink to the purchase of ‘clothing, good food, all the comforts of life’, and thus ‘reward the grower and manufacturer’ and the former drinker.15 Temperance was part of a broadly defined rational recreation movement that sought to reform non-productive forms of masculine leisure like gambling, blood sports and visiting prostitutes by replacing these older pleasures with family-centred, hetero-social, educational and productive pastimes.16 Working with a different notion of the working-class consumer, but one that still emphasized the difference between moral and immoral pursuits, the Co-operative movement created a variety of lasting alternatives to free market consumerism. Shopping at the Co-op remained a significant consumer experience in the twentieth century, but, as Gurney argues in this volume, its political power was eclipsed as a new individualistic notion of the consumer emerged at this time.17 James Vernon has noted that photography and the development of the illustrated press in the mid-nineteenth century helped instil empathy between disparate groups, which laid the foundation for the idea of the society that emerged with the post-1945 welfare state.18 Not all of these reformers and agencies agreed upon which goods or behaviours were moral and interpretations could change quickly. Nevertheless, they fashioned working men and women as potential citizens who could bring about political change. They all emphasized, in the words of Peter Gurney, how consumption was ‘a vital arena in which class relationships were defined and renegotiated’.19

The rational citizen-consumer competed with an equally prominent understanding of consumers as gendered, passionate and sensual beings. Scholars have shown how this conception of the embodied and gendered consumer influenced the expansion of overseas trade, empire, industrialization, urbanization and retail changes. During and after the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the desire for porcelain, silk, tobacco, cotton, sugar, cocoa and tea, for example, reconfigured the nature of long-distance trade, propelled the development of slavery and other forced labour systems, stimulated industrialization within and beyond Europe and thereby altered the balance of power between Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas.20 The sensual consumer also influenced some of the most significant retail a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- CONTENTS

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- Part I: Gender, Sexuality and Youth: Cultivating and Managing New Consumers

- Part II: In and Beyond the Nation: The Local and the Global in the Production of Consumer Cultures

- Select Bibliography

- Index