- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book presents a compelling ethnography of the changes Tajikistan faces at the turn of the twenty-first century as seen through the eyes of its youth. It discusses the ethnographic gaze on the tremendous cultural changes being played out in post-Soviet Tajikistan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Muslim Youth by Colette Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

HISTORY OF TAJIKISTAN

Each nation has its own unique history that plays a significant part in its subsequent development and which therefore must be grasped in order to comprehend its current situation. In the case of Tajikistan, its people are particularly proud of their long and illustrious history, which they trace back beyond Alexander the Great, and which at one time put them at the center of world civilization.

Tajikistan became a nation state in 1991, having started out as a Soviet republic in the 1920s under Stalin’s leadership. Before this, the area was part of a large amorphous mass of land in the central part of Asia. By the eleventh century it had been so dominated by Turkic tribes that it came to be called Turkestan (Glenn 1999: 51). More recently, this region was split between Russian or Western Turkestan, which was incorporated into the Soviet state, and Chinese or Eastern Turkestan, currently the province of Xinjiang in the People’s Republic of China. Unless otherwise indicated, the history that follows is common to all the peoples of Western Turkestan.

EARLY HISTORY TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

Central Asia is part of Inner Asia, an area stretching east-west from the Carpathians to Korea, and north-south from the Arctic Ocean to the Himalayas.1 The Central Asian segment consists of the central steppes and part of the southern desert rim, as well as reaching south to the foot of the Himalayas in the Hindu Kush and Tien Sen mountains. It contains two major rivers, the Oxus (Amu-darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr-darya), both originally flowing into the Aral Sea.

As early as 7000 BC, the main inhabitants of Central Asia were probably nomadic pastoralists. A few millennia later Central Asia became the seat of Zoroastrianism, which can be considered in some sense to be the first world religion (Adshead 1993: 33). After 500 BC, it formed a significant part of the first interregional world empire, that of the Achaemenids, which stretched from China into Africa. Shortly thereafter the region was absorbed into the empire of Alexander the Great.

By the seventh century AD, much of Central Asia was Buddhist. However, less than two centuries later, the region had largely converted to Islam, leading to a great flowering of philosophy, science, and the arts that made the region one of the foremost centers of world civilization. The founder of algebra and of arabic numerals, Al-Khwarazmi (780–850), came from Central Asia. The poet Firdausi (d. 1020), author of the Shah-nâma, and Ibn Sînâ (980–1037; known in Europe as Avicenna), the foremost medieval philosopher best known for his Qânûn, were both born in Central Asia and spent most of their lives there.

In 1206 Chinggis Khan was elected Great Khan. A few years later along with his Mongol hordes he conquered most of Central Asia. By the end of the century, the Mongols had conquered China. They occupied parts of southern and southeastern Asia, and penetrated as far into Europe as Kiev and the Adriatic Sea. From 1300 to 1370 Central Asia was ruled by the Chaghatai Khanate, led by descendents of Chinggis Khans second son. Between 1370 and 1405, the great Tamerlane, or Timur, became the most powerful conqueror Central Asia had ever seen. He built stronger and better-equipped armies than ever before and at the same time strengthened Turkestan as a trade route. Tamerlane’s successors were the Timurids, who reigned until 1510.

The trade route espoused by Tamerlane was known as the silk route, along which merchants brought silk, spices, and other exotic goods from China to Europe. This was the route that had gained fame in Europe in the early four-teenth century as a result of Marco Polo’s published descriptions of his travels.

After 1510 a number of lesser powers ruled Central Asia, among them the Uzbeks. In the late eighteenth century, the latter divided their polity into the three city-states of Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand.

In the early nineteenth century, Central Asia was experiencing an economic renaissance. It was hampered in its growth, however, by its low population, apparently due to the use of birth control (Adshead 1993: 201). The low population rates continued until after World War II largely due to epidemics of measles and other contagious diseases, many of which resulted from contact with the Russians. These caused extremely high rates of infant and child mortality. Only from around 1960 did living standards improve enough to encourage rapid population growth (Harris 2002).

In the mid-eighteenth century Russia started its advance into Central Asia. In 1865 it conquered Tashkent,2 one of the most important cities in the region. In 1868 the area that now encompasses Tajikistan came under a Russian protectorate, and by the end of the century the entire sweep of Western Turkestan was under its control.

This vast region was inhabited by many different peoples. Among them were nomadic tribes, who wandered over it with their large herds of cattle, living in enormous felt tents called yurts. Their descendants are the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz of today. Sedentary tribes who lived by cultivating the land had settled in the fertile oases, which had been divided into small fiefdoms, each ruled by a khan or emir. Among them were the peoples known today as Uzbeks and Tajiks.

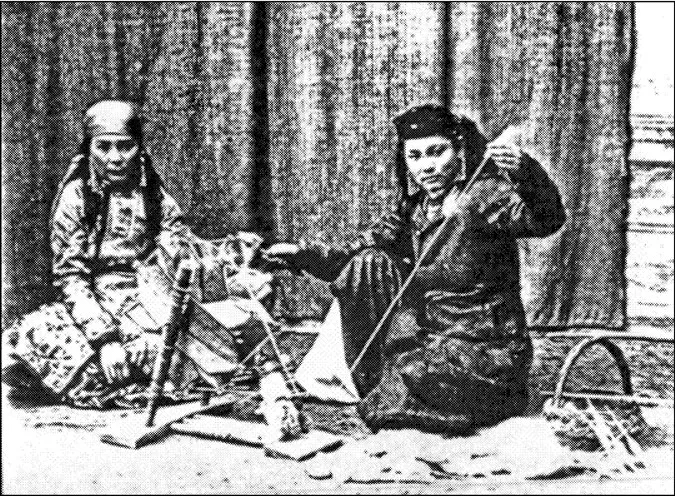

By the time of the Russian conquest, these sedentary peoples had become devout Muslims, living according to sharia. Female seclusion was practiced, especially in urban areas. According to Muslim law, men’s responsibility was to serve as breadwinners, while women carried out domestic labor. They were not forbidden to carry out income-generating activities, however. They could sew, produce silk, or make handicrafts, always provided their menfolk procured the necessary raw materials and sold their goods for them.

Only in the most desperate cases did women head households or support their families financially. However, wealthy men with far-flung business inter-ests might take a wife in each place and entrust to her the running of their estates in that location (Harris 1996).

Married women could leave home only with the explicit permission of their husbands and/or mothers-in-law. Upper-class women might pride themselves on never leaving the house from the time of their marriage to their death (Meakin 1903: 193). However, most women did leave home on occasion, whether to visit the local bathhouses or their parents (Donish 1960). When they did so they would be escorted by relatives and bear on their bodies the “curtain” (purdah) that hid them from the view of strangers.

In what is now northern Tajikistan and in much of Uzbekistan this curtain consisted of the chachvan and faranja. The former was a thick veil made of black horsehair. This covered the face uniformly without finer mesh or holes at eye level. Over it was worn the faranja, a cloak that hung over the head and reached down to the ground, concealing the entire body (Harris 1996).

Before the Russian conquest, almost the only educational establishments in Turkestan were religious schools, which largely taught rote repetition of the Qur’an. Women religious leaders—known as bibiotuns or bibikhalifas—taught girls and led female prayer groups (Fathi 1997; Kamp 1998). Medressas provided more sophisticated, but still largely religious, education for young men. In the late nineteenth century Russians set up schools, mainly for their own people, and a progressive group of Tatars known as Jadidists started “new method” schools with a secular curriculum (Kamp 1998: 26–63; Tokhtakhodjaeva 1995: 26).

Figure 1.1 Turkestani women spinning, circa 1900 (Meakin 1903: 38)

Turkestan grew a number of crops that could not be cultivated in Russia. The most important was cotton. One of the chief purposes of the Russian conquest had been to fill the gap left by the fallout from the American civil war that had deprived Russia of its main source of this material.

Because of this the Russians strongly promoted cotton cultivation. In order to increase it, they intervened in both the land system and the modes of production. At that time, land in Central Asia was not individually owned but rather allotted by either the secular overlords or the religious authorities. This state of affairs did not suit the Russians, who introduced the capitalist system of land as private property. Together with pressures on farmers to produce ever larger quantities of cotton, this ended up bankrupting many peasants, who were forced to sell their land, and ended up as impoverished agricultural laborers (Vaidyanath 1967: 45n51).

Figure 1.2 The faranja and chachvan at the end of the nineteenth century (Schwarz 1900: 268)

HISTORY OF THE SOVIET PERIOD

The continuation of these trends might have produced significant social change by forcing large masses of peasants off the land (cf. Marx 1867: 876), but the process was interrupted by World War I. Turkestan almost slipped out of Russian hands when in 1916 the government tried to conscript local men. Their wives sparked off a revolt in their determination not to allow the Russians to deprive their families of their breadwinners (Kamp 1998: 98–104). In the midst of the ensuing chaos came the Revolution; the Tsar was deposed and the Bolshevik Party assumed power under Lenin’s leadership. By 1920 the whole of what is now Tajikistan had come under Soviet rule (Robertson 2000: 327).

The immediate post-Revolution years were difficult and chaotic. Problems intensified because of a lack of food. The Tsarist government had induced local farmers to plant cotton rather than grain, assuring them this could easily be imported. During World War I the train lines were cut. This prevented grain arriving from the north. The result was a serious famine, estimated to have killed almost a million people, which took years to recover from (Etherton 1925: 154).

Despite Lenin’s reassurances, the Central Asians were highly suspicious of the Bolsheviks. This was particularly true of the region that now forms the southern part of Tajikistan. Until the 1920s this had been in the Emirate of Bukhara, not under direct Russian rule like most of Western Turkestan. Its inhabitants had therefore had little contact with Russians. They were extremely religious, having followed a very strict form of sharia law, and therefore especially difficult to convince of the benefits of joining a regime that was preaching atheism. They formed a resistance group known as the Basmachis, which in the mid-1920s mounted an unsuccessful military campaign against the Red Army (Rakowska-Harmstone 1970). After the Basmachi defeat, the Central Asians were forced to accept the inevitability of Soviet rule. This was especially galling, since the new regime was not content with military victory alone but was determined also to impose itself culturally on its subject peoples.

The impact of this policy was very strongly felt in Central Asia, where the Soviet regime made great efforts to produce cultural transformation. A major issue of contention was the attempt to change social organization from reliance on local elites to adherence to Party politics and cooperation with local Party cells.

Even more contentious was the issue of religion. Atheism was one of the lynchpins of the socialist regime. While it had been possible to disestablish the Orthodox Christian Church and shut down most public worship in Russia, the situation in Central Asia was very different.

The population was mainly Sunni Muslim, which had neither a central governing body nor even official clergy. Moreover, while Russians were able to separate their religious from their cultural identity, Central Asians were not. This made it virtually impossible to persuade the population to accept atheism as a ruling principle, since this would have been tantamount to denying their own cultural identity. As a result, Central Asians continued to identify as Muslims throughout the Soviet period.

Gender identities proved to be another particularly conflictive issue. In the 1920s the Bolsheviks used multiple strategies to gain the support of Central Asian women, conceptualizing them as a surrogate for the proletariat they had been unable to find in rural Turkestan (Massell 1974). These were strongly opposed and in the end only partially successful.

Therefore, the Bolsheviks decided that the best long-term tactic would be to convert the younger generation of Central Asians to its ideologies. One of the chief instruments for achieving this was the school, and Soviet ideology became an important part of school curricula.

A further tactic was to try to put an end to the institution of the extended family whereby married sons lived in their parents’ homes (Rakowska-Harmstone 1970). The Bolsheviks reasoned that physically separating young people from their parents would result in psychological separation. When parents and their married offspring lived apart, it was thought, each unit would behave like a separate nuclear family. The result was supposed to be that young people would become increasingly open to outside influences, which would facilitate their acceptance of the new ideas introduced by the Party (Bacon 1966: 168).

The government tried to achieve this aim by building apartments too small for the cohabitation of extended families. However, in Tajikistan at least, physical separation appeared to make little difference. Parents still kept a tight rein over their children. Young people who attempted to move outside their parents’ sphere of control were sharply brought to heel or else cast out of the family circle. Moreover, irrespective of place of residence, decision-making continued to take place in the extended family council, where older men had the most say. As a result of the firm control each generation kept over the next, the pace of social change was considerably slower than the government had hoped for (Rakowska-Harmstone 1970: 62, 275).

In the early 1930s, the Bolsheviks...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Editor Preface

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION: MUSLIM YOUTH

- 1 HISTORY OF TAJIKISTAN

- 2 TRADITIONALISM VERSUS MODERNITY

- 3 FAMILY RELATIONS

- 4 EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT

- 5 ROMANTIC FRIENDSHIPS

- 6 MARRIAGE AND THE FAMILY

- 7 TENSIONS AND TRANSITIONS

- Notes

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index