- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this new edition of his widely acclaimed study, William Duiker has revised and updated his analysis of the Communist movement in Vietnam from its formation in 1930 to the dilemmas facing its leadership in the post-Cold War era. Making use of newly available documentary sources and recent Western scholarship, the author reevaluates Communist revolutionary strategy during the Vietnam War. Based on primary materials in several languages, this respected work is essential for an understanding of Vietnam in the twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Communist Road To Power In Vietnam by William J Duiker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

In 1995, the Vietnamese people were preparing to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon in the spring of 1975. In the United States, major TV networks, newspapers, and newsmagazines are focusing attention once again on the Vietnam War and on the multiple effects it exerted on a generation of Americans. Government officials, journalists, and scholars are once again engaged in what appears to be an unending debate over the causes of the war and the lessons it poses for U.S. foreign policy.

When the first edition of this book was published in 1981, the debate had already begun as hawks and doves traded bitter charges over the reasons for the U.S. defeat in Indochina. As I viewed it at the time, one of the salient characteristics of that debate was that it concentrated almost exclusively on the reasons for the U.S. defeat. Little attention was devoted to the reasons for the enemy's victory. In my judgment, that focus on U.S. mistakes, however understandable in the context of the time, resulted in a misleading impression of what had really happened in Vietnam. Although the U.S. government under a series of presidents from Harry Truman to Richard Nixon had made a number of serious miscalculations about the situation in Indochina, under normal circumstances the overwhelming size of the U.S. military commitment would have brought about a result favorable to the United States. The explanations for the Communist victory lay more in Hanoi and Saigon than in Washington—in the extraordinary self-discipline and dedication of the Communist leadership and its followers and the chronic incapacity of their non-Communist rivals to present an effective response.

It was for that reason that I wrote this book.

The nature and shape of this victory had already attracted considerable attention from scholars, journalists, and government officials, and a number of studies on the subject had appeared in Western languages.1 What was lacking was an analysis of the Communist rise to power, from the Party's origins in the colonial period to the final triumph in Saigon in the spring of 1975, in an historical context. With this book I hoped to fill that gap.

The project was the outgrowth of a process that began well over three decades ago. As a foreign service officer serving with the U.S. Embassy in Saigon in the mid-1960s, I was struck by the extraordinary tenacity and impressive organizational capacities of the Viet Cong in the war that was then just under way. The contrast with the performance of the Saigon regime was noteworthy. After leaving government service for an academic career, I decided to study the topic. In a study published by Cornell University Press in 1976, I investigated the emergence of the Communist Party as a major factor in the Vietnamese nationalist movement prior to World War II. Some of the salient factors in the Communists' success and the corresponding weaknesses of their nationalist rivals began to emerge in that earlier study, but it was clear that what the Party had achieved by the start of the Japanese occupation of Indochina in 1940 was no more than a promising beginning. By no means did it satisfactorily explain the success achieved in the struggles that followed. Thus gradually emerged my decision to continue my investigation of Vietnamese communism through the conflict with the French after the Pacific War down to its triumph in the recent war.

There were, I recognized, important obstacles that impeded any serious study of this nature. First and perhaps foremost, it was a topic of considerable magnitude. In an effort to avoid superficiality I restricted my concern to one of the central issues raised by the conflict—the nature of the Party's revolutionary strategy toward the seizure of power. The book was not a comprehensive history of the war or of the Communist movement per se. Nor did it deal with domestic policies in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) except where such policies affected war strategy. Finally, it did not pretend to treat in detail French or American efforts to counter Communist activities in Vietnam, except where such efforts obviously related to the evolution of Communist strategy. Although such issues are vital to an overall understanding of the war, they must be left for future analysis.

A second obstacle was the relative paucity of reliable materials published in the DRV. A few studies had appeared on various aspects of the war and its origins, but only a handful were available to foreign scholars. As a result, much remained obscure, not only about the decisions themselves but also about the entire nature of the decision-making process. For years it had been surmised that there had been disputes within the Party leadership over strategy, yet the reality was always a matter of conjecture. The researcher was therefore reduced to foraging for material—in statements of the official press, in books or articles by leading Party officials in Flanoi, or in official documents, diaries, and training-session reports captured during the war.

A third problem was that of credibility. Most of the materials available on the war, official as well as unofficial, are colored by partisanship. Official documents issued in Hanoi, Paris, and Washington often reflected the government line. Books and articles by academics and journalists were frequently colored by the bias of the writer. Because of the sharp emotions involved, dispassionate judgments were difficult to come by. The key issue for this study, of course, is the reliability of materials published by the DRV. Obviously, much of this information is propagandistic. Some documents and official statements were deliberately designed to be misleading. For years, Hanoi denied that its troops were involved in the war in the South and described that conflict as an effort undertaken by the National Liberation Front (NLF) of South Vietnam. More recently, the Party has dropped this pretense and asserts with pride that the full resources of North Vietnam were brought to bear in order to bring the conflict to a successful conclusion. (Washington and Paris, of course, were sometimes guilty of similar practices, although perhaps not on a systematic basis.) Under such circumstances, how can official statements or documents issued in the DRV be considered trustworthy? There is no easy solution to this problem, but I believe that most official materials contain at least an element of truth and that a trained researcher can overcome this obstacle and (with an occasional exception) determine the reliability of the materials available. In my research, I chose to rely on the veracity of such materials unless there appeared to be persuasive reasons not to do so. As more information emerged from Hanoi, I hoped to have ample opportunity to judge the accuracy of what was currently available.

Today the situation has improved significantly. Monographic studies, memoirs, and documentary collections published in Vietnam and elsewhere are beginning to fill the gaps in our knowledge of the Vietnamese side of the conflict. These materials provide the researcher with a clearer picture of what decisions were made, who made them, and why. Although a number of crucial questions have not yet been resolved, we are today much closer to obtaining a balanced picture of the war as viewed from all sides, not just from Washington and Saigon but also from Hanoi, Moscow, and Beijing.

The Vietnam War has had a searing effect on the American political culture and the American consciousness. It is important to understand why U.S. policymakers acted and thought as they did, and what the consequences were. But it is also vital to understand the conditions in Vietnam and the viewpoint and objectives of the Communist leadership. It was, after all, none other than Dean Rusk and Robert McNamara, two of the most prominent architects of the Kennedy-Johnson strategy in Vietnam, who conceded that they had miscalculated the intentions and capabilities of their adversary in Hanoi. And although the Vietnam War has been over for twenty years, it remains the standard by which all subsequent foreign policy crises are judged.

There are indeed lessons to be learned from the war, among which is the proposition that the United States should not rush blindly into international involvements with little understanding of the factors involved. The case of Vietnam also convincingly demonstrated that U.S. firepower has limited effectiveness when applied with restraint against a determined and well-organized adversary. Finally, it showed that comparisons across time and space should not be made without due attention to the local historical and cultural factors involved.

But in some ways, it is probably unfortunate that the Vietnam War has served as a touchstone for every foreign policy challenge that the United States has faced in the past two decades. For one of the key lessons that emerges from these pages is that the case of Vietnam is unique. The historic encounter in Vietnam was the product of an explosive combination of circumstances—the tragic legacy of a bitter colonial experience, the rise of a revolutionary wave throughout the region, the global rivalries of the Cold War, the emergence of an "event-making man" in the person of Flo Chi Minh, and the history and character of a tough and ingenious people. Although the Vietnam War does suggest certain serious risks in U.S. military intervention in the Third World, it does not demonstrate that every such intervention will necessarily result in a repeat of the Vietnam experience. As U.S. policymakers discovered to their gratification in 1991, the Persian Gulf was not Indochina.

The story of how the Communists won in Vietnam, then, cannot and should not be used as a primer for those who hope to wage a successful war of national liberation, still less by those who hope to defeat one. But it should serve as a useful object lesson for those who choose, despite all evidence, to ignore the facts of history.

2

The Rise of the Revolutionary Movement (1900–1930)

Ho Chi Minh once remarked that, for him, the road to communism went through nationalism. Put in concrete terms, the most significant event in Ho Chi Minh's intellectual life took place in 1920 when, as a young patriot living in Paris, he obtained a copy of Lenin's famous "Theses on the National and Colonial Questions," presented at the Second Congress of the Comintern in Moscow. At that moment, by his own account Ho became a Leninist, primarily because Lenin's elucidation of Communist strategy in colonial areas seemed to provide the best means of liberating Vietnam from French colonialism.1

The incident is of more than symbolic importance, for in Vietnam, the roots of the Communist movement are deeply intertwined with those of the anticolonial movement. And while Vietnamese communism and nationalism have frequently appeared to go their separate ways, the Communist movement throughout most of its existence has been able to project itself before the mass of the population as a legitimate force representing Vietnamese national aspirations. This symbiotic relationship between nationalism and communism in Vietnam is in no small measure responsible for the triumph of the forces of revolution over the Saigon regime in the spring of 1975.

Vietnamese Nationalism

It is therefore appropriate to begin this study with a brief examination of the dynamics of Vietnamese nationalism. When Marxist doctrine first appeared in Vietnam shortly after World War I, Vietnamese nationalism was in a state of transition.2

The Vietnamese traditionally had a strong sense of national identity, a consequence of two thousand years of struggle to protect their indepen

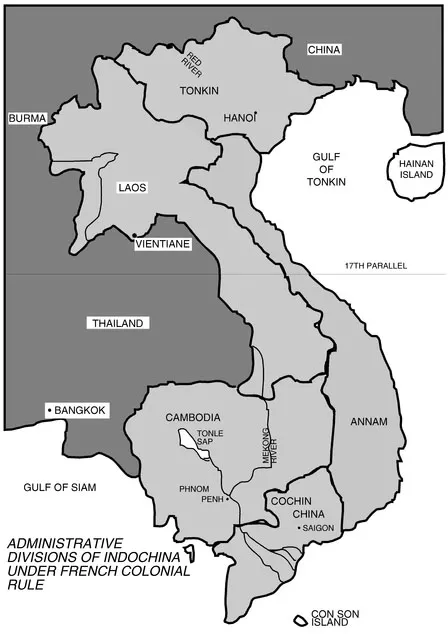

dence from China, their powerful neighbor to the north. Early resistance to the French conquest, led by patriotic elements from among the traditional Confucianist ruling elite, had been irrevocably broken in the mid-1880s when the guerrilla bands led by the rebel leader Phan Dinh Phung Were defeated in the hills of Central Vietnam. As for the imperial court at Hué, it had by then become a mere instrument of French rule, an effete relic of past glories. Vietnamese territory was divided at the whim of Paris. Cochin China, in the South, became a French colony. Tonkin, the old heartland of Vietnamese civilization surrounding the Red River valley, was legally a protectorate, but in practice French authority was virtually total. Only in Annam, comprising the coastal provinces in the center, was the court permitted to retain the tattered remnants of its former authority.

The decline of the political force of traditional society was quickly reflected in society at large. By the turn of the century, the authority of Confucian ideology and social institutions and of the scholar-gentry class that played the major role as defender of the social order and propagator of official doctrine was beginning to erode. Here French colonial policies exerted a strongly corrosive effect. Influenced by the popular conviction that France had a humanitarian purpose—a mission civilisatrice to bring Western culture to its new Asian possession—colonial officials tended to espouse policies that would undermine the influence of traditional Confucian institutions and customs in Vietnamese society. The teaching of the Chinese written language, the traditional means of transmitting Confucian doctrine in Vietnam, was discouraged, and the use of a transliteration based on the Latin alphabet—called quoc ngu or the national language—was actively promoted. The civil service examination system, the vehicle for recruitment of young Vietnamese into the official bureaucracy, was abolished, and a new educational system that, while retaining a few elements of the traditional Confucian system, placed primary emphasis on Western culture and values was gradually put into effect.5

The inevitable effect of such reforms was to undermine the role of the Confucian scholar-gentry class as the protector of the political, social, and ethical values of Vietnamese society. While for a time the influence of the traditional elite remained relatively unimpaired at the village level (particularly in Annam, where the power of the mandarin continued to reign supreme), its status in the cities and provincial towns rapidly declined. The effects of this decline were soon to be injected into the bloodstream of the embryonic Vietnamese nationalist movement. After 1900, a new generation of patriots took up the cause of Vietnamese independence. Themselves the offspring of elite families, they were aware of the larger changes taking place elsewhere in Asia, particularly in China and Japan, and tended to reject a return to the past, preferring instead a comprehensive reform of Vietnamese society along Western lines. Most famous was Phan Boi Chau, the holder of an advanced degree in the traditional educational system, who refused a career in the imperial bureaucracy and founded a revolutionary movement to overthrow French rule and set up a constitutional monarchy in imitation of the Meiji Restoration in Japan. An admirer of Sun Yat-sen, after the 1911 revolution in China Chau became a republican.

Characteristically, the efforts to introduce Western values and institutions into Asian societies have been ambivalent in theory and ineffective in practice. Such was the case in Vietnam. The generation of "scholar-patriots" received their knowledge of the West not from personal experience but indirectly, from the writings of reformist Chinese intellectuals like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao. Because of this second-hand knowledge, their grasp of the new world beyond Vietnamese frontiers was superficial and their understanding of mass politics limited. Although their courage and patriotism were well documented, their strategy and tactics were primitive; and after Chau was arrested in South China in 1914, the movement lost its dynamism and its influence in Vietnam rapidly declined.4

The disintegration of the scholar-patriot movement coincided with the emergence of new social forces that were destined to play a major role in the next stage of Vietnamese nationalism. French commercial activity was rapidly transforming the economic character of Vietnamese society and, by the end of World War I, had given rise to two new social classes of growing importance—an urban middle class and a proletariat. The new Vietnamese middle class was by no means homogeneous. At the upper end of the spectrum was an increasingly affluent commercial and professional bourgeoisie, composed for the most part of bankers, land speculators, absentee landlords (many with substantial landholdings in the Mekong delta), engineers, agronomists, doctors, and merchants. This group benefited substantially from French economic policies. In many cases its wealth was an immediate consequence of the French presence. A few of the more prominent members came from traditional elite families, but most appear to have been self-made men. This new urban bourgeoisie thus had few links with the past, and as its wealth and social prominence increased, bourgeois families increasingly took on a Western cultural veneer—sending their children to French schools, drinking wines and dining on French cuisine, and living in colonial villas in the tree-lined suburbs of Saigon. Indeed, it was Saigon, Vietnam's "frontier city," that became the nucleus of this new class. Located relatively close to the rubber plantations along the Cambodian border and to the newly opened rice lands in the lower Mekong delta, Saigon was the one city where fortunes could be made quickly, even by enterprising Vietnamese.5

Below this urban upper crust of the middle class was the noncommercial urban intelligentsia, composed of teachers, journalists, clerks, minor functionaries, and students. To a substantial degree this class came from families with a scholar-gentry background in which emphasis had traditionally been placed on community service and education rather than on the accumulation of wealth. In that sense, this class can be viewed as the first generation of scholar-gentry elite to grow up under French colonial rule. Though some of its members obtained advantages from the French presence and thus at least tolerated the colonial regime, the scattered information available suggests that many came from families that had refused to collaborate with the conquerors and had thus inherited a legacy of stubborn hostility to the colonial regime.6 This new petty bourgeois intelligentsia formed a potential primary source of discontent against French colonial rule in Vietnam.

The final new element was the proletariat. Totaling about 100,000 in 1918, as a rule this working class was employed in enterprises linked to the colonial regime: in factories in Saigon, Vinh, and Hanoi; in the coal mines of upper Tonkin; on the rubber plantations of Cochin China; and at dockside in the port cities of Saigon and Haiphong. Though a few had become skilled workers, the majority still had one foot in the surro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Rise of the Revolutionary Movement (1900-1930)

- 3 Out of the Ashes (1930-1941)

- 4 Prelude to Revolt (1941-1945)

- 5 The Days of August (August-September 1945)

- 6 The Uneasy Peace (September 1945-December 1946)

- 7 The Franco-Vietminh War (1947-1954)

- 8 Peace and Division (1954-1961)

- 9 The Dialectics of Escalation (1961-1965)

- 10 War of Attrition (1965-1968)

- 11 Fighting and Negotiating (1968-1973)

- 12 The Final Drama (1973-1975)

- 13 Prospect and Retrospect

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Book and Author

- Index