![]()

1 Introduction

The retail sector is an integral part of a national economy. From the political economy point of view, all consumer goods have surplus values locked up in them, and the surplus values are not realized until the consumer goods are purchased by consumers through various distribution channels (Blomley, 1996). As such, retailing is the pivotal link between production and consumption; and the accumulation of retail capital is achieved through “repeated acts of exchange” between consumers and retailers (Ducatel & Blomley, 1990: 218).

In a typical capitalist market economy, the retail sector consists of diverse types of retailers. Some of them are corporate retailers, which operate multiple stores in the form of a chain and with a complex organizational structure. Others are independent retailers with a single store location. In terms of ownership, corporate retailers can be further differentiated as publicly traded companies and privately owned chains. Relative to independent retailers, corporate retailers are small in number, but they command the largest share of the consumer market.

The success of a retail business depends on two general factors: the location of the retail outlets, and management of the business. Both factors are equally important. If the business is located in the wrong place with the wrong customer base, it will not generate expected sales. Similarly, if the business is poorly managed and operated, it will not perform well, even if the location is right.

Retailing is a subject of study for two groups of scholars and students—business management and geography—but they approach the subject from different perspectives. The former are concerned with consumer behavior and business organizations, including logistics, merchandising, marketing, in-store display, and supply chain; whereas the latter focus on selection and determination of business locations and delimitation of trade areas in localized markets. Despite being enrolled in different programs, students of geography and business management often take courses from “the other” school for professional development. For many students, retail geography has been a popular subject, as it frequently leads to rewarding professional jobs in retail corporations, banks, commercial real estate companies, and business consulting firms.

ADVANCEMENT OF RETAIL GEOGRAPHY AS A SUBJECT OF STUDY

Retail geography, which originated as marketing geography, but has lately been called by some business geography, was created as a separate field of study in the mid-1950s in the United States. William Applebaum is widely regarded as the chief architect of this field of study. He emphasized that marketing geography should be viewed essentially as an applied, rather than a purely academic subject (Applebaum, 1954). He also considered that the best place to develop the field of marketing geography was in business itself. Marketing geography was further developed and advanced by such leading geographers as Brian Berry and David Huff. In its first 40 years, retail geography was primarily concerned with the identification of the demand for various goods and services (i.e., areal expression of demand), and with the spatial arrangements for the supply of them (i.e., areal structure of the system of supply) through an efficient distribution network (Davis, 1976). In general, this orthodox retail geography (as it is being called by some contemporary retail geographers) was founded on a predictive and instrumentalist epistemology, and most of its ontological presumptions are linked to the neo-classical economic view of the world, such as the central place theory, gravity model, and distance decay function, which conceive of space as a neutral container, at most affecting transportation costs. Further, it maintained a focus primarily on the retailer rather than on the supply chain as a whole, and was restricted to concentrating on the geography of stores but neglecting the geography of such important trends as the centralization of retail distribution operations. The traditional maxim of “location, location, location” was well reflected in the orthodox retail geography as a study focus (Jones & Simmons, 1993).

The early 1990s witnessed a major paradigm shift in the study of retail geography. The orthodox retail geography was re-theorized and reconstructed by Wrigley, Lowe and a few other European economic geographers, and a new geography of retailing was advocated to reflect the series of important changes in the global economy. The new geography of retailing has three important characteristics in comparison with the orthodox retail geography (Lowe & Wrigley, 1996).

First, it takes a political economy approach, seeing retail capital as a component part of a larger system of production and consumption (Blomley, 1996). As such, its study scope extends to include production spheres in the system of circulation activities, particularly the production–commerce interface, namely the changing relations between retailers and suppliers. Aided by advanced technologies, retailers have developed logistically efficient stock-control systems and centrally controlled warehouse-to-store distribution networks. These systems permit shorter and more predictable lead time, with important implications for configuration of new retail spaces as well as reconfiguration of existing retail spaces.

Second, it is concerned with the geography of retail restructuring and the grounding of global flows of retail capital (i.e., sinking of retail capital into physical assets in overseas markets) and its spatial outcomes in the form of retail facilities of different formats. Innovative retailers, teamed up with developers, create differentiated spaces of retailing in the same market or different markets, and premeditate them to induce consumption (Ducatel & Blomley, 1990).

Third, it calls for much more serious treatment of regulations because the regulatory state is an important force influencing both corporate strategies and geographical market structures. In the view of Lowe and Wrigley (1996), the orthodox retail geography was remarkably silent about regulation and the complex and contradictory relations of retail capital with the regulatory state. With the exception of a discussion concerning the constraining influence of land use planning regulations, the transformation of retail capital appeared to take place in a world devoid of the macro-regulatory environment that shapes competition between firms and the governance of investment. In the context of the new retail geography, regulations include both public-interest and private-interest interventions, with the former concerning the relations between retailers and consumers, and the latter concerning relationships between retailers and suppliers (including producers).

While the new geography of retailing advanced the theoretical development and expanded the study scope of the subject, there is no place in its agenda for traditional concerns with store location research, GIS, and models that are commonly used to address such strategic issues as evaluating existing branch performance, impacts of new store openings/store closures/store relocations, and finding the optimal location for a new outlet (Birkin et al., 2002). Even Wrigley and Lowe (2002: 17) themselves acknowledge that “we are conscious that some of our readers may feel that we have moved a long way away from what they might regard as the heart of geographical perspectives on retailing.” There is clearly a need to integrate both the orthodox retail geography and the new geography of retailing.

THE RETAIL PLANNING PROCESS AS THE ORGANIZATIONAL FRAMEWORK OF THIS BOOK

The success of a retail corporation depends on a well-defined planning process, in which retail geographers have an important role to play.

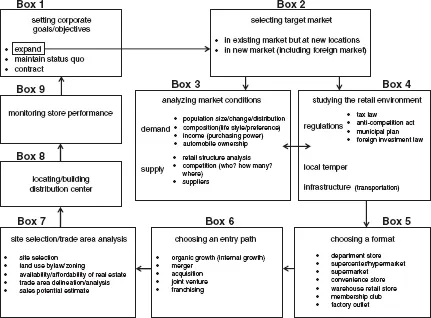

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the retail planning process starts with the retail company setting up its development goals and objectives on the basis of the company’s market strength and the resources it possesses (see Box 1 in Figure 1.1) The goal of resource-rich companies is usually to grow or expand. There are two general types of growth strategies: non-spatial and spatial. The former refers to driving sales from the existing stores, often by reducing prices, increasing merchandise offerings, and improving service and store environments (Epstein, 1984). The latter refers to store network expansion by adding more retail outlets at more locations. For companies that are mediocre performers, the goal is often to defend and maintain market share while improving performance of the existing stores. The weak retailers are most likely to choose to divest, either reducing operation scales by closing unprofitable stores, or closing the operation entirely.

Figure 1.1 The Retail Planning Process.

If a company decides to expand, the next step is to select a target market. (Box 2). A market can be as large as a country or region, and can be as small as a city or town. Alternative strategies range from expanding in the same market to entering a new market. A suitable market is selected based not only on an extensive analysis of the market conditions but also on a careful examination of the holistic retail environment. This is particularly important when a new market is being considered by a corporate retailer. At the international level, some countries are defined as developed markets with well-established trading rules and regulations, while others are described as emerging markets, which are converging towards the developed markets in advanced economies. While having not yet reached the level of market efficiency with strict standards in accounting and securities regulation to be on par with advanced economies, emerging markets are nonetheless sought after by multinational retailers for the prospect of high returns, as they often experience faster economic growth as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), though investments in these markets are often also accompanied by higher risks due to political instability, domestic infrastructure problems, and currency volatility.

Market conditions are assessed for both demand for and supply of consumer goods (Box 3). Typically, the level of demand is estimated with three fundamental factors—population size, population composition, and disposable income—which in combination determine demand quantity and purchasing powers. In some cases, the level of automobile ownership is also considered because it affects consumer mobility and hence shopping behaviors. Projected population change (either increase or decrease) is an important consideration in market condition analysis as well, as it facilitates decision making with regard to the scale of retail development so as to meet future demand while also minimizing investment risks and potential sunk costs.

On the supply side, market condition assessment includes both retail structure analysis and competition analysis. This helps to gauge the level of market saturation or “crowdedness”, the strengths and weaknesses of competitors, and “the market space” left for new entrants. Walmart introduced its Sam’s Club to Canada in 2006. In the next three years, it opened six outlets in southern Ontario, where Costco had already established a strong presence with a large base of loyal customers. Apparently due to underestimation of the competitiveness of Costco in Canada and southern Ontario in its planning process, the six Sam’s Clubs could not make a profit and had to be closed three years later, in 2009.

The holistic retail environment includes regulations, public attitude (i.e., “local temper”), and infrastructures (Box 4). Different countries, or even different provinces and municipalities, can have different regulations, such as tax laws, an anti-competition act, land use bylaws, and even foreign investment policies. In capitalist market economies, governments rarely own or operate retail stores, except for a few selected consumer goods (such as the non-merit goods of alcoholic beverages, cigarettes, and cannabis). While retailers enjoy a high degree of freedom in business decision making, governments do intervene in the retail industry with regulatory measures, often in the form of public policies, to mitigate negative impacts. In turn, these policies, which are supposed to reflect the values of the society, impose limits on the retailer’s freedom to deal with competitors and conduct business with suppliers and consumers, thus affecting retail operations and the overall market structure. The importance of regulations is appropriately recognized in the new geography of retailing.

In the Western democracies, the public attitude towards certain retailers is also an important consideration in retail planning. In the United States, anti-Walmart sentiments in some communities have derailed the retailer’s plans to enter a number of local markets. The opposition is more than against the big box format; it has also been against the way Walmart conducts business, including its anti-union corporate culture, low wages, and heavy-handed treatment of suppliers. Walmart now operates 4,800 outlets across the United States. Yet, it has not been able to enter New Yor...