![]() Part I

Part I![]()

1

Art, Fashion and Music in the Culture Society

‘I’m classically trained, though I’ve since broken all that down. But the training was important, otherwise you don’t really know why you are doing something and it’s just gratuitous . . .’ (who does he think he is, Picasso?).

(Interview with Guido, hairdresser, Independent on Sunday 15/3/98)

The intention here is to explore some consequences of the ‘aestheticisation of everyday life’ from the viewpoint of Britain in the late 1990s, which various cultural theorists including Jameson (1984), Featherstone (1991) and Lash and Urry (1994) have described. This broad social process raises a number of questions. These include the changing meaning of art in such a context; the further implications of the breakdown between ‘high and low culture’; the growth of creative labour markets; and the challenge to judgement on questions of cultural value. All four of these dimensions have recently become prominent and are seen when we explore the new cultural triumvirate; fashion, art and popular music, currently the subject of political attention by the Creative Task Force set up in July 1997 by the newly elected Labour government.

It is now almost fifteen years since Jameson argued that culture was the logic of late capitalism. More recently the German sociologist, Herman Schwengell, has proposed that we now live in a Kulturgesellschaft, Culture-Society (Jameson 1984, Schwengell 1991). All the more reason then to consider what has happened to culture after postmodernism. If both these writers are right, and culture now fires the engine of economic growth, it is not surprising that it becomes a key issue for government. As cultural phenomena seek global markets on the back of home-grown creative energies, and with ‘culture becoming strategically linked to inward investment’ (Ford and Davies 1998: 2), New Labour proclaims its enthusiasm for art, fashion and pop flying the flag for Britain. The image of 1960s Swinging London updated to a 1997 picture on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine featuring Patsy Kensit and Liam Gallagher in bed, draped in the Union Jack, and Naomi Campbell on the catwalk in a Union Jack dress designed by Alexander McQueen, shows what happens when cultural practices like fashion design and pop music get drawn upon a populist wave into promoting the national good abroad.

This kind of seemingly innocuous ‘banal nationalism’ (Billig 1995) strikes a discordant, uncomfortable note, especially for non-white people for whom ostentatious flying of the Union Jack in parts of London associated with racist activity signals a real threat to safety. The Union Jack flown outside Damien Hirst’s Quo Vadis restaurant in Soho in London is a self-mocking signal that art nowadays is both commerce and tourism, and commerce itself is also art. It is a provocation to those he sees as part of the political correctness establishment and, as several writers have already pointed out, this gesture is in tune with the ‘art offensive’ of the young British artists. But seeing the world in terms of political correctness is in itself a mark of affiliation. It describes those who repudiate feminism, anti-racism and other similar movements as constraining, authoritative and almost bullying political practices (or else as simply dull and worthy).

The convergence of Damien Hirst’s flag flying and New Labour’s endorsement of the Cool Britannia initiative which emerged from the DEMOS report (the think tank with close links with new Labour) on re-branding Britain, represented an attempt to re-define culture and the arts away from their more traditional image as recipients of funding towards a more aggressively promotional and entrepreneurial ethos (Leonard 1998). They were to become ‘more British’, but for the international market. The rebranding was proposed on the basis of old Britain’s image being out of date (John Major’s ‘warm beer and cricket’) and in need of both modernisation and rejuvenation. But in this context Tony Blair’s clumsy embracing of popular music, culminating in various photo-opportunities showing him shaking hands with Noel Gallagher, backfired when two months later, in April 1998, the New Musical Express ran a seven page special feature on how young musicians were disenchanted with New Labour policies. Gradually the media over-exposure of the ideal of Cool Britannia became unattractive to the kinds of figures which the government was hoping to use as examples of successful and creative British talent, and quietly the tag was dropped.

While the concerns of the Creative Task Force remain relatively opaque, a more detailed analysis of the culture industries is urgently required. Despite the interest in the cultural sector on the part of big business, the grassroots of cultural activity remains small scale. The upsurge of creative activity which has recently come to fruition on the art, fashion and music front has done so in the adverse economic circumstances of the Thatcher years. This may be the single most important feature which they share in common, that the designers, musicians and artists have all depended on Thatcher’s Enterprise Allowance Scheme (EAS) and have all struggled to survive in the space between unemployment and self employment.1 No records exist of the precise number of fashion designers, artists and musicians who were recipients of the EAS in the ten years of its existence from 1983 to 1993. However, various reports and studies all point to the important role it played in under-writing the early work of the young British artists (O’Brien, quoted in Harlow 1995), the expansion of the fashion design sector (McRobbie 1998) and the popular music industry. It is equally difficult to get a clear picture of how many people are employed in the culture industries as a whole, since that could embrace all communications workers, television and press, film, leisure and entertainment. Given this broad spectrum, figures vary wildly according to which categories of work are included although there is agreement on the expansion of the field and its overwhelming concentration in London (Garnham 1990; Pratt 1997).

Given the importance of the culture industries it is remarkable how under-researched they have been and it is the sparsity of research across the whole sector which accounts for the reported difficulties faced by the Creative Task Force in formulating policy. For example, with the introduction of the Job Seekers’ Allowance in 1997, young musicians who depended upon the dole and eked out an impoverished existence for themselves while signing on until such a time as they might land a recording contract were, it appeared, now going to be forced into work. This, argued Alan McGee, a member of the Creative Task Force and owner of Creation Records, would mean the end of creative talent in Britain’s music industry. Without the dole young musicians would not be able to write songs, rehearse, and hang about in the pub waiting for inspiration. Following a certain degree of uproar across the music press, the government surprisingly backed down. Behind the scenes a deal was set up which was intended to ensure that the talented would not be pushed out into work but would be placed on work experience placements in the music industry. With the fine details of this deal still to be published at the time of writing, the idea of young musicians having to perform to a panel of government-appointed experts as a sort of creative means-testing, to qualify for exemption from having to take a less creative job, seems somewhat unwieldy as social policy. Will there be enough placements to fill this demand? Is there not a stronger case to reintroduce some new version of the EAS for new recruits into the culture industries? After all, its track record is not so disastrous. Tricky was on an EAS scheme when he released his first record and there are plenty of other examples.

At present, policy is at best haphazard and cloaked in administrative mystery. At worst, it is publicity-led and seemingly thought up on the spur of the moment.2 I would argue here that for policy makers some of the key issues will be: (a) how cultural activities which have historically depended upon state support can actually be capitalized. Is it possible to envisage a scenario where practising artists are not just self sufficient but are ‘income generating’?; (b) how young people can be supported to create careers for themselves in these fields, where they move from poorly paid freelance work into sustainable careers, that is, how breadline existences can be turned into a business ethos; and (c) how public sector bodies which have traditionally supported artistic and creative activities can themselves be revamped in order to respond more directly and more imaginatively to changes in the cultural sector.

Sensation: Art as ‘Cultural Populism’?

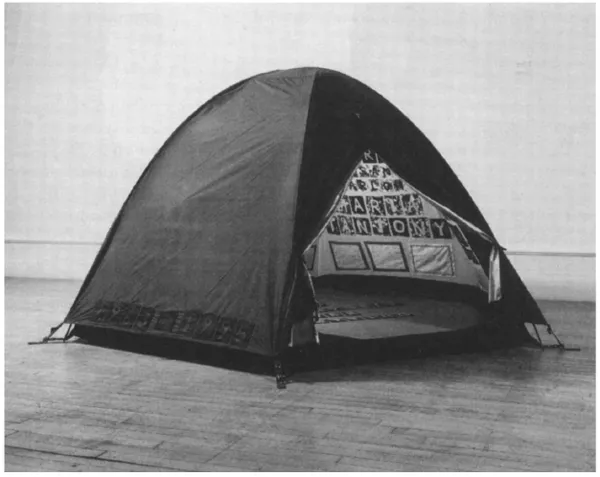

What exactly are these cultural changes? The Sensation exhibition held at the Royal Academy in London (18 September to 28 December 1997) demonstrates how the work of the ‘young British artists’ (including Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread, Mark Wallinger and the Chapman brothers, among others) is now phenomenally successful (300,000 visitors) and simultaneously less special. This new brand of art is no longer the prerogative of the elite, and this less special status warrants more attention. Not that we are witnessing a new democracy or a radicalization in the field of art. The young British artists distance themselves from all the art theory, the Marxism and post-structuralism which they may have come across at some point in their training. Tracey Emin’s reported enjoyment of studying Marxism and feminism while at art college is touched with irony. The art work comprising the infamous tent in which she named everyone she had ever slept with owes more to the bawdy ‘girls just wanna have fun’ humour of More! magazine than it does to her feminist elders, Cindy Sherman or Mary Kelly.

There is, then, a rebuff to the seriousness of the political art and photography of the 1980s generation. A whole range of art magazines, galleries, cultural theorists and artists themselves are instantly forgotten. These include, for example, Camerawork, magazines like Ten Eight, influential cultural theorist Victor Burgin, and also the generation of black British artists whose work began to appear in galleries from the mid 1980s, such as Chila Burman, Mitra Tabrizian, Sonia Boyce, David Bailey, Keith Piper and film-maker Isaac Julien, all of whose worked engaged at some level with cultural theory, with questions of identity and with new ethnicities. In addition there is no sign of the whole wave of art work which developed in relation to the crisis of AIDS and HIV. Some critics, notably John Roberts, have argued that this disengagement with theory allows a new licentious and profane philistinism to emerge, particularly as the Jameson-inflected works of postmodern art have become over-institutionalized (Roberts 1998). The cynical, apolitical individualism, as well as the weary, not to say tawdry, disengagement of many of the pieces (Sarah Lucas’ soiled mattress with phallic shaped fruit pieces casually thrown on top or, for that matter, Tracey Emin’s tent) certainly says something about how art now perceives itself and where it also places itself. Acknowledging and even endorsing what Kobena Mercer has described as the ‘vulgarity and stupidity of everyday life’ (Mercer 1998), is casual, promiscuous, populist art which wishes to be repositioned inside the chat show world of celebrity culture, alongside the sponsorship deals, in the restaurants and at the very heart of consumer culture. This is art made for a prime-time society, where daytime television encourages the parading in public of private misfortunes (‘My wife weighs 900 pounds’ was the title of one Jerry Springer show broadcast on British television on 7 August 1998). Exposure and confession are recurrent themes in Sensation. The power of the popular media to penetrate every moment of our daily lives makes the tabloid-isation of art inevitable.

Figure 1.1 Everyone I have ever slept with 1963–1995 by Tracey Emin

Source: Photograph by Stephen. White. Courtesy of Jay Jopling/White Cube, London

It is tempting, but not entirely satisfactory, to explain all this on the grounds that art nowadays is simply good business and that these artists are ‘Thatcher’s children’. Liz Ellis has suggested that in this context the new art has reneged on all feminist achievements and shorn itself of all recognisable ethics, it is art as part of the political backlash (Ellis 1998). Convincing as this account is I would argue for a rather different approach to the young British artists. Ensconced inside the consumer culture, less lonely and cut off, the new art simply becomes less important, it downgrades itself, as an act of conscious bad faith. The Sensation exhibition did not require the usual quantities of cultural capital to enjoy it. It did not invoke cathedral-like silence. It self-consciously staged itself as shocking but was also completely unintimidating. In this respect art has come down from its pedestal, it has relieved itself of the burden of distance and of being expected to embody deep and lasting values. But, if not all art can be great and if there are more and more people seeking to earn a living as an artist, then this is a realistic, not merely a cynical, strategy. The new ‘lite’ art also means the blurring of the boundaries between where art stops and where everyday life commences. The singularity of art begins to dissolve. Is it a sculpture or a dress by Hussein Chalayan? Is the video by Gillian Wearing entided ‘Dancing at Peckham’ effective because it isn’t real art, just a small slice of urban life? Given the ‘Nikefication’ of culture, are the artists (most of whom emerged from Goldsmiths College in the early 1990s) literally ‘Just Doing It’? Maybe they are simply making things based on ideas. And, in so doing, they are deliberately challenging the art world with its patrician critics and its lofty standards. In the late 1990s, instead of demystifying art (the traditional strategy of the left) the yBas are redefining it, repositioning it and, to use the language of New Labour, ‘rebranding art’ in keeping with what it means to be an artist today and how that cannot mean being pure about sponsorship and, consequently, very poor.

As students from more diverse backgrounds enter art school, Bourdieu’s notion of the artist being able to stay poor in the short term thanks to some small private income in order to achieve success on the longer term is no longer appropriate (Bourdieu 1993a). There has to be some way of being an artist and making a living. We must also take into account the historical moment of the yBas. They have been brought up with their peers to venerate and value the conspicuous consumption of the 1980s, they are part of what Beck has called the ‘me first generation’ (Beck 1998). Few of the generation educated through the 1960s within the full embrace of the welfare society have really come to grips with the power which money and consumerism has over a younger generation. This new love of money crosses the boundaries of gender, class and ethnicity and, as Beck has also described it, is not incompatible with strongly expressed views about social injustice, poverty, the environment and human rights (ibid., 1998). Rather than be startled by the new commercialism in contemporary art we should therefore recognise how slow an older generation of social and cultural theorists have been to recognise this issue.

The experience of Sensation, the strangeness and the slightness, might therefore be enough and perhaps we need not expect more of art than this. Challenging, indeed confounding, critical judgement and thus freed from the burden of being classified in terms of great, good, mediocre or bad, there is a sense that there is nothing much to lose. (Some critics have referred to the self-conscious strategy of making bad art.) In an aestheticised culture art becomes another transferable skill. Train as an artist to become a DJ. Work nights in a club or bar and get a commission from the promoters to do an installation. Make a video, take photographs etc. Art can now be pursued less grandiosely. And considering that there are fewer traditional jobs to return to if all else fails, the yBas seem to be aware that ducking and diving is no longer the fate of unqualified working-class males but almost surrepticiously has crept up on us all. Sociologists have written extensively about the new world of work characterized by risk, uncertainty and temporary contracts. But their attention so far has not been focused upon creative work. For this reason nobody has posed the question of how much art, music and fashion the culture society can actually accommodate. How many cultural workers can there be?

Although there is great diversity within the work of the yBas, there are a number of features which are common throughout. First, there is a generational revolt against the conviction and enthusiasm of their Marxist and feminist predecessors which has produced a marked anti-intellectualism in their work. Second, they relate to popular culture by simply adopting it wholesale, its gestures, language and identity, without attempting to explore it and then elevate it back into the art world and its circuits. Popular culture is staged ‘post-ironically’ as presentation rather than as representation, as if to reassure the viewer that there is absolutely nothing clever or complex going on here. These artists deliberately seek out the most downgraded forms, for example the ‘Sod You Gits’ headline of the 1990 piece of the same name by Sarah Lucas. This flat endorsement of popular culture and its transgressive pleasures describes a hedonism also connected with this particular ‘tabloid loving’ generation.

Even extreme or violent material remains devoid of social or political content or comment. Sensation exists in a generationally specific ‘chill out’ zone where, after the pleasure, thoughts of death and mortality make a seemingly inevitable appearance. But this is not marked by a sudden gravity. There is curiosity, a touch of morbidity (as in Ron Mueck’s model of a miniature corpse carefully laid out, naked and still sprouting hair), but otherwise a casual interest in death and decay. This forges another link with the tradition of British youth cultures. Two pieces in Sensa...