- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Historical Atlas of Religion in America

About this book

First Published in 2001. Charting the history and geographic development of American religions, The Routledge Historical Atlas of Religion in America displays in vibrant visual and textual detail the intimate relationship between American spiritual belief and the events that formed the nation. Mirroring the variety found in America's religious past and present, coverage focuses on such diverse topics as: Indigenous American Religions, Russian Orthodoxy, French Catholicism, The Puritans, Judaism in the Colonies, The Great Awakening, American Metaphysical Movements, African American Churches, The Mormons, Islam, Buddhism and German Sects in Colonial America. Loaded with more than 50 full-color maps, charts, and illustrations, The Routledge Historical Atlas of Religion in America is an indispensable reference for those interested in the American religious experience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I: INDIGENOUS AMERICAN RELIGIONS, PREHISTORY–PRESENT

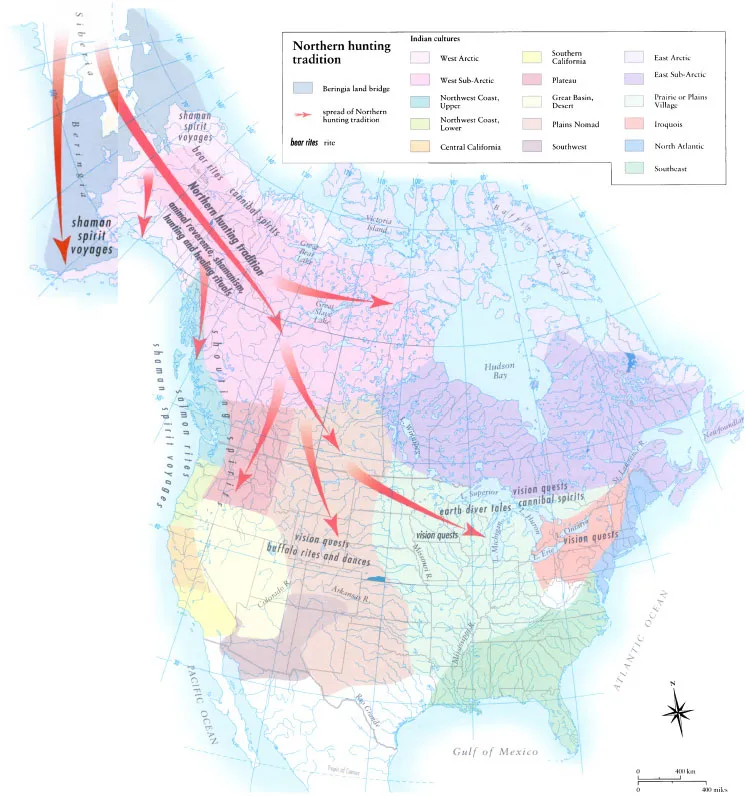

American religious history began some 30,000 to 50,000 years ago when, according to archaeologists, the first human beings set foot on the North American continent. An Ice Age expansion of the Arctic ice cap reduced sea levels sufficiently to expose an area of land currently submerged beneath the Bering Sea and called Beringia. This tundra region attracted eastward-moving hunters from northeastern Siberia, who brought with them their Paleolithic Asiatic cultures and belief systems.

The Beringian crossing ended when milder climatic conditions and rising sea levels obliterated the land bridge, perhaps 10,000 years ago. By then the descendants of the Siberian migrants had spread over the tundra, grasslands, deserts, plateaus, and forests of the Americas, adapting to a wide range of environments and developing their Paleolithic religiosity into a correspondingly wide variety of forms. Meanwhile, Indonesian, Micronesian, and Melanesian peoples of south Asian origin carried other Paleolithic religious forms eastward across the Pacific Ocean to the islands of Polynesia and, by about 500 CE, northward from Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands to the Hawaiian Islands. By the time of European colonization, about 75 million people inhabited the Americas, perhaps 10 million of them in what is now the United States. They were divided into hundreds of ethnic groups, spoke hundreds of languages, practiced an array of subsistence techniques, developed many different patterns of social organization, interacted with each other through trade, migration, and warfare, and devised a kaleidoscopic range of religious systems to address the circumstances of existence. In shaping and reshaping their religions in response to experiences of migration, adaptation, and intercultural exchange, they established enduring patterns of American religious life.

This Southeastern shell gorget from about 1000 CE depicts a shaman, suggesting the retention of Northern hunting traditions in Southern agricultural religious practice.

This diversity complicates any attempt to present indigenous American religions in general terms, but historians and anthropologists have identified several broad characteristics and constructed models by which to make sense of their variety. Perhaps the most basic point about Amerindian religion is that those behaviors and attitudes we term “religious” were for them the central orienting mechanism in a single seamless reality of cosmos, landscape, culture, society, and economy. American aborigines understood themselves as participants in a world of spiritual power at once natural and supernatural—called Wakan by the Sioux, Orenda by the Iroquois, Manitou by the Algonkians, and Mana by Hawaiians—upon which they depended for survival and which they encountered mainly through its effects in the natural world. This spiritual force infused humans, animals, plants, landscape features, and natural phenomena and bound them into an integrated web of existence. Humans were only one—and by no means the most powerful—of nature’s active powers.

Native Americans expressed such beliefs in their various origin myths, intended to explain cosmically their geographic location, their relationship to the environment, and their social and cultural systems. These myths were expressed in rituals, which differed from group to group but aimed through sacred words, songs, gestures, and objects to align humanity with the spiritual world and to harness its powers for personal or group welfare. The assurances of ritual were particularly important at crucial junctures in the life of the group (before and after hunts and wars, for example, or at the time of planting and harvest) or of the individual (puberty, illness, or death). Many groups identified certain individuals, called shamans (usually but not always men), as possessing special spiritual gifts that gave them authority to conduct rituals, but most groups also emphasized ordinary people’s connection to the spiritual world and encouraged personal ritual encounters with it, as men might do before hunting or women when menstruating.

This Shoshone hide painting of a buffalo dance suggests the importance of the buffalo and hunting to ritual life on the Plains.

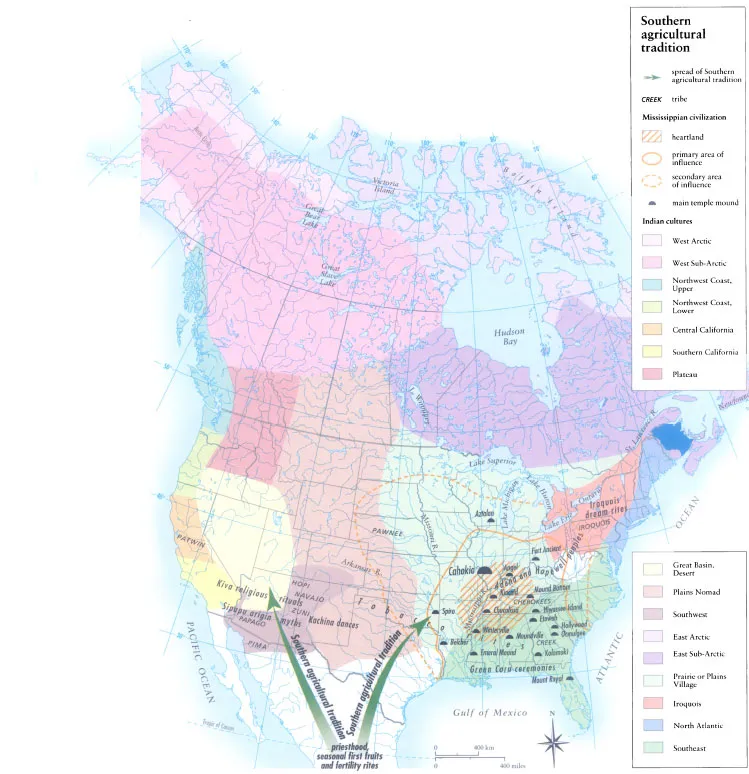

In addition to such broad commonalities, scholars have identified two broad and interpenetrating “traditions” within North America’s precontact indigenous religions. The first was a Paleolithic “northern hunting tradition” that came to the continent with the first Siberians and spread eastward and southward; the other was a younger “southern agrarian tradition” that accompanied the development of settled agricultural economies in Mesoamerica and spread northward with maize cultivation. After contact with white Europeans and Americans, Amerindian groups developed a spectrum of religious responses, often categorized into “revitalization” and “accommodation” movements, by which they resisted or adapted to an expanding Euro-American presence and rethought their relations with the land.

Northern Hunting Religions

Northern hunting religions developed from those of Paleolithic Siberia and Beringia. Their features were evident wherever hunting was common but remained most pronounced in northern North America.

America’s hunting peoples regarded animals, on which they depended for survival and which appeared well adapted to environmental conditions, as superior in wisdom and power and deserving of respect and reverence. Their origin myths typically featured local animals as earth’s shapers and first inhabitants. Great Lakes tribes, for instance, attributed hills, valleys, and streams to a Great Beaver that dredged soil from a primeval sea and a hawk that flapped its wings to dry it. A Great Hare then summoned human beings into existence and taught them to survive. Many northern tribes were divided into clans claiming descent from animal ancestors.

Hunting and animals dominated ritual life as well. Throughout the Northeast and on the Plains, hunters sought the supernatural aid of bear, eagle, and badger spirits in dramatic vision quests. Shamans conducted collective rites that used imitative gesture and costume to petition desired animals prior to hunting and offered ceremonial thanks to the animal spirits afterward. Arctic Eskimo solemnly addressed Grandfather Bear, while tribes of the Pacific Northwest returned the skeletons of a season’s first salmon catch to rivers in order to ensure continued supplies. On the Plains, Sioux, Pawnee, and Osage ritual reflected dependence on buffalo.

The shaman was particularly important in most hunting tribes. Most shamans of the Americas beckoned spirits to approach and possess them, but those of the Arctic, Bering, and north Pacific Coast regions retained the Siberian practice of spirit flight, their souls traveling great distances to contend with powerful spirits and ensure successful hunting. Other groups looked less to shamans than to medicine men or secret societies for healing magic.

Hunting groups dealt gingerly with the female power of fertility, thought harmful to the spiritual power men required for hunting. Tlingit men, for instance, considered continence a prerequisite for prehunt visions, and men of whaling tribes sometimes avoided their wives for the entire whaling season. Menstruating women were ceremonially isolated from the group and forbidden contact with all objects touched by the men. Young women learned of their power in rites of passage at first menses.

Native religions often symbolized environmental hazards as spirits. Many Eskimo peoples, like their Siberian ancestors, feared a cannibal spirit representing what was probably a grim reality of Arctic life. The Ojibwa of the Great Lakes likewise hoped that the cannibal spirit Windigo would not visit in nightmares. Eskimo hunters also imagined a half-human, half-animal spirit that, like the vast whiteness of the landscape, threatened to hypnotize and destroy them. Harmful shouting spirits might bedevil hunters in the cold, windy forests of western Canada and the Pacific Northwest. Such were the challenges, difficulties, and religious expressions of hunting life in the North.

Southern Agricultural Religions

Maize agriculture, developed in Mesoamerica about 3000 BCE, sparked settled village life, complex social structures, an intensified astronomical and meteorological awareness, and characteristic religious patterns in which priesthoods and rich collective rites fostered community bonding and addressed the challenges of agricultural life. Such patterns spread gradually northward into what is now the United States.

Evidence of urban centers and ceremonial burial mounds among the Adena and Hopewell peoples of the Ohio Valley suggests that agricultural religion had reached the region by 1000 BCE. It was more fully developed by the Mississippi Valley civilization, which flourished about 1250 CE, cultivated corn, constructed temple mounds for collective rituals, and centered on the city of Cahokia. This civilization disappeared long before Europeans arrived, but it left behind what are now the oldest religious structures on the American landscape and powerfully shaped subsequent cultures in the lower Mississippi Valley.

Planting tribes revered and expressed in myth the power of agriculture. The Hopi and Zuni of the Southwest imagined that their ancestors emerged from holes in the earth (sipapu) after Father Sky or Father Sun brought rain to Mother Earth and that they learned to plant corn from Corn Mothers. They conducted many rituals in subterranean kivas in recognition of these origins. Southeastern peoples also explained human origins in terms of descent from the sky and understood Father Sun as the source of life.

Agricultural ritual celebrated and sought to control plants, planting, harvest, rain, and sun. Petitions to Father Sun at summer and winter solstices were common in the Southeast. Cherokee and Creek Green Corn ceremonies and similar rites thanked and perpetuated seasonal rhythms by sacrificing the “first fruits” of important crops. Ceremonial cornmeal offerings likewise characterized the Southwest. Many Southern tribes considered tobacco a particularly effective means of petition. On the Plains, the hunter-gatherer Pawnees and others smoked it through calumets to honor the Corn Mother and the Keeper of Buffalo. In the Southwest, where rain was rare, the Hopi and Zuni held summer kiva rituals and public ceremonies invoking rain-bringing ancestral spirits (kachinas) through cornmeal, pollen, and dance. Near the current Mexican border, the Papago and Pima sought rain through song and ritually consumed cactus cider—tribes farther south used corn liquor—every June.

Agricultural religions never ceased resembling the hunter traditions from which they evolved. Indeed, the common roots of the two traditions, the migration of peoples, and variations in physical and cultural environments produced a complex reality in which agricultural and hunting rites were more often than not mixed. The Creeks of Alabama and Georgia, who hunted and planted, retained shamans and hunting rituals alongside their fertility observances. The Iroquois, who migrated northward to New York from the Ohio Valley around 1200 CE, retained Mississippian features rare in the North: complex social organization, a full ceremonial calendar, and a priesthood that conducted rituals for corn, beans, and maple syrup. The Navajo, who migrated southward from the subarctic to the Desert Southwest, combined the visions, healing magic, and cold-weather concerns of Northern hunters with the priests and rain ceremonies more typical of the region. Such systems suggest the dynamism and complexity of pre-Columbian American religion.

A Zuni kachina doll. These figures were used by tribes in the desert Southwest to summon rain-bringing spirits.

Ancient Hawaiian Religion

Not all of the indigenous religions of what is now the United States originated in those of Beringia and northeastern Siberia. Another important eastward movement of peoples, religions, and cultures occurred much farther south, where Malaysian and Indonesian islanders of south Asian descent, driven by adventure, warfare, or a search for food supplies, pushed across the Pacific Ocean, gradually settling first the islands of Micronesia and Melanesia, and then those of Polynesia, including Tahiti, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. Archaeological data suggest that northward oceanic migration had led inhabitants of the Marquesas to Hawaii by around 500 CE—making the islands probably the last in the Pacific to be occupied by human beings—and that larger streams of Tahitians arrived in Hawaii between 900 and 1300 CE. Native Hawaiian religion and language became increasingly distinct over time but show clear similarities to the Tahitian. Hawaiian and Tahitian cultures in turn point to their shared origins in the Asian and oceanic cultures to their west.

Ancient Hawaiian religious belief and practice were much like those of other Paleolithic peoples, emphasizing the spiritual power assumed to underlie every aspect of life, its specific manifestation in various natural forces and places, its exercise by humanized deities of varying functions, and its manipulability at the hands of ritual specialists. More specifically, Hawaiian religion resembled those of other Polynesians, with such powerful geological and geographical realities as...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- I Indigenous American Religions, Prehistory–Present

- II European Christianity Colonizes America, 1500–1867

- III Colonial Formations, 1607–1800

- IV Protestant Expansion in the Nineteenth Century

- V World Religions and Growing Pluralism, 1850–Present

- VI Religions of the Modern Age

- Chronology

- Further Reading

- Index

- Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Routledge Historical Atlas of Religion in America by Bret Carroll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.