eBook - ePub

Transforming Universities with Digital Distance Education

The Future of Formal Learning

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Transforming Universities with Digital Distance Education explores the ways in which higher education stakeholders can apply and leverage the benefits of online learning. Systems-wide access, scale and quality are achievable goals but require forms of teamwork and financial modelling beyond those at the instructor or programme level. This book's organisational view tackles the systems and practices that will help senior managers and decision-makers guide an entire institution away from dysfunction—incremental progress, insufficient capacity, high costs and generic products—and towards the macro-level implementation and operations of effective online pedagogies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transforming Universities with Digital Distance Education by Mark Nichols in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Thirty years from now the big university campuses will be relics. Universities won’t survive. It’s as large a change as when we first got the printed book.

(Drucker, as cited in Lezner & Johnson, 1997, para. 70)

Education is on the brink of being transformed through learning technologies; however, it has been on that brink for some decades now … never before has there been such a clear link between the needs and requirements of education, and the capability of technology to meet them. It is time we moved education beyond the brink of being transformed, to let it become what it wants to be.

(Laurillard, 2008, para. 2)

My mother and father were determined: my sister and I would go to university. I remember both of us understanding this before we were 10 years old. We simply assumed we would go to university as we advanced through the New Zealand compulsory schooling system. Neither of my parents went on to higher education, yet they saw the opportunities it could unlock. They wanted their children to benefit from the choices and lifestyle they saw university graduates had access to. I remain very, very grateful. My sister and I were among the first of our extended family on both sides to graduate with degrees; her in law, mine in business. For me, the bachelor’s degree would be only a first step into a very interesting, rich, diverse, rewarding and often challenging career in education.

Higher education continues to provide opportunity, but access to it has changed radically between my generation and my children’s. In the United Kingdom, as in New Zealand, Australia and various other nations, the proportional cost of education paid by the student relative to public subsidy has dramatically increased. Yet, demand continues to be strong. In 2018 it was estimated that an additional capacity for a further 300,000 new students will be required across the United Kingdom university sector by 2030 (Bekhradnia & Beech, 2018), raising serious questions about how universities will be able to cater for this extra demand. Without rethinking the dynamics of how universities work, future options are threefold: turning less-qualified students away, placing excessive demands on the public purse for new campuses, or compromising personalisation through massification. None of these options is desirable, nor inevitable.

The foundation of this book is the notion that higher education can be accessible, scalable and highly personalised all at once, without compromising quality or student outcomes. Its thesis is that digital distance education (DDE), linked to online learning, holds the solution. If we were looking today to invest money into a university sector where accessibility, scalability and personalisation were characteristic, we would start with the same educational outcomes (substance) but would seek to design a different educational system (means of facilitation). We would seek to achieve the same things but would pursue them differently.

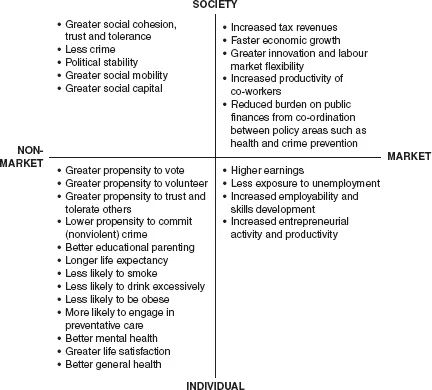

Education in Context

Education changes lives. It provides opportunity, perspective and prospects to the individuals who experience it, and economic and social benefits to the societies that nurture it. A 2013 report by the Department for Business Innovation & Skills in the United Kingdom summarises a wide range of market and non-market benefits for both society and the individual that result from higher education (Figure 1.1). It is these benefits that continue to drive and justify the massive social investment in higher education. In 2016, excluding R&D costs, New Zealand spent some US$11,910 per full-time equivalent student and the United Kingdom US$18,405. Australia was close to New Zealand, at US$10,791 per student (OECD, 2019). Yet while costs are readily quantifiable, the returns of education tend to be indirect and intangible. It is difficult to quantify the benefits of developing social cohesion, human potential and self-actualisation, even if the average economic benefit per graduate is calculable. Education is both a public and social service, and a private and personal experience. Finding the best ways of sharing the costs for these benefits across public and personal budgets is an enduring political problem.

The OECD report Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators observes that graduates with higher-order skills earn more, are more likely to be in good health, take care of the environment and participate in public life (2019). However, the same report states that between 2005 and 2016 “spending on tertiary institutions increased at more than double the rate of student enrolments … private sources have been called on to contribute more” (2019, p. 10). Costs, particularly directly to students, continue to increase.

Over the past two decades, funding for higher education has increased at a disproportionate rate to student volumes. Data from HESA (the Higher Education Statistics Agency) shows that 2017/18 higher education provider income in the United Kingdom was 114% of what it was in 2014/15, even though the volume of students was only 103% of 2014/15 levels.1 Perhaps this relative increase in income is in response to the situation faced by the sector at that time, where ‘overall the sector is predicting lower surpluses, a fall in cash levels and a rise in borrowing, signalling a trajectory that is not sustainable in the long term’ (HEFCE, 2015, p. 28). It is not all bad news: across the same period access to higher education has improved for disadvantaged groups, and there is a greater proportion of new students entering the system. Nevertheless, costs continue to increase relative to student volumes.

Figure 1.1 The Market and Wider Benefits of Higher Education to Individuals and Society.

Source: Department for Business Innovation & Skills, 2013, p. 6. Re-used under the terms of the Open Government Licence, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/.

My first degree left me with no debt. In fact, I first went to the University of Waikato campus in Hamilton, New Zealand with about NZ$20 in my pocket. I signed up with a local bank, received an immediate NZ$500 overdraft capacity, paid all my fees, bought all my textbooks and had plenty of credit to spare. I received a student allowance that mostly covered my living costs. My undergraduate years were the last in New Zealand for fee-free tertiary education; since then student fees have regularly ratcheted up, as has student debt from loans. As I write, the typical university student in the United Kingdom will incur somewhere around £40k in personal debt as they earn their degree. No wonder many are questioning the viability of a university degree, and no wonder politicians are seeking to extend competition, encourage efficiency and grow capacity.

Education as a Wicked Problem

Education is key to advancing civilisation, economic development and self-actualisation. It is also a wicked problem prone to shifting priorities, practices and expectations. All elements of education – from access to it, what it is concerned with, how it is taught; from the suitability of various subject areas to the ethics of changing someone’s perspective; from its overall objectives to its epistemological emphases – are open to debate and disagreement. Given the importance and controversy associated with education, it is vital that decisions related to how it is funded and expressed be made deliberately and transparently. The difficulty is that all views about all aspects of education will inevitably have an element of truth to them. This is characteristic of all wicked problems: any and every position will have both adherents and opponents, with associated agreement and disagreement. One person’s enlightenment is another’s indoctrination; providing massive student choice across multiple subject areas provides valuable variety in the eyes of some, yet is viewed as a pointless waste of limited funds by others; effective teaching in the eyes of one person is dismissed as excessive, unnecessary or overly contextualised by the next.

Debate, constant and open, ensures that no destructive extremes dominate but also inoculates against systematic innovation. It the nature of a wicked problem that it will never be solved, never be settled. This could be why educational philosophy suffers from what Siegel calls ‘a benign neglect’ (2009, p. 5): it is risky to propose solutions to education’s many maladies, because biting and accurate critique will always follow.

Yet we must continue to look for solutions. At the time of writing most university students studying in the United Kingdom pay £9,250 a year in tuition fees. These figures ignore the costs to each individual graduate in terms of their living costs, debt servicing and opportunity cost as they study. If we were able to completely start designing universities from scratch today, mindful that it costs each student well over £30k in private funds and opportunity cost to become a graduate, I suspect the system we would design to cater for student volumes close to two and a quarter million would be rather different to that incumbent today. While much would remain recognisable, most would be radically different. In my view, the core elements – accredited qualifications, valid learning outcomes, quality criteria, assessment, the parts that constitute the substance of education – are well worth carrying forward. Other parts – timetables, attendance, academic responsibilities, campuses, lectures, formal exams, the facilitative aspects of education – require substantial critique and revision.

Redesigning Higher Education

If we were developing a higher education system from scratch, what would it aim to achieve? I propose the system would be designed to provide accessible, scalable and personalised education, shaped to the interests of society and students.

• By accessible, I mean a system that welcomes those new to it and is flexible enough to make ready allowances for individual circumstances.

• By scalable, I mean a system that can dynamically cater for changing student numbers, above a break-even number, in cost-effective ways.

• By personalised, I mean a system that offers more support where more is needed, that draws on each individual’s experiences and perspectives, and emphasises feedback.

• By being shaped by the interests of society, I mean a genuine attempt to meet the reasonable demands of society for publicly funded graduates to participate in the economy and community.

• By being shaped by the interests of students, I mean the opportunity for students to be engaged, enlightened and empowered as elements characteristic of education.

The terms engaged, enlightened and empowered add up to education (as outlined in the next chapter); ultimately it is these things that students and society reasonably expect to be characteristic of their investment in education. Tempting though it often is for advocates of digital change to promote the trinity of technology, online and learning, this is to mistake means for ends. Engaged, enlightened and empowered are the three terms that define education in this book, as it is these three things that education is uniquely concerned with.

I also propose that a redesigned system would not settle for any compromise to quality standards or student completion rates. Any worthwhile higher education system must be able to demonstrate the integrity of its activities and its contribution towards society in the form of developing work-ready graduates and free-thinking citizens. Speaking personally and with the benefit of hindsight, if I were a fee-paying student in formal education today, I would anticipate learning about ideas that surprise me, challenge me, change me and prepare me for a professional career. I would anticipate engaging with these ideas, not merely being expected to simply acknowledge or later recall them. I would anticipate feedback that insightfully informed me about my understanding, not just my knowledge, and that directed me into personalised advice for self-improvement as to how I think and express myself. So, I would expect to be enlightened as to how I think. I would appreciate learning activities that were clever, that led me to new ways of understanding and that drew on innovative approaches. I would expect my university to learn about me as I studied, and for the people I interacted with to know who I was. Of course, I would also expect my educators to know their stuff and to apply the best of pedagogical knowledge to their task. Ultimately, I would expect to be empowered as a graduate, to be able to interact confidently and competently within the social and employment milieu I aspired to be a part of. I would expect my qualification to give me opportunities to flourish in the ways that best align with my life orientation. A major part of this would be, economy permitting, the ability to get work in a profession related to my interests and be able to contribute to activities in my chosen sphere.

In other words, I would expect my fees to provide me with an effective education. Also, with the benefit of hindsight, I would seek to study part-time alongside a substantial part-time job. During my undergraduate years distance study was an option, but it lacked popular reputation as a viable alternative to the campus. There is no reason why this should be the case now.

A Twenty-First Century Higher Education System: Would We Start Where We Are?

If we were seeking a higher education sector characterised by accessible, scalable and personalised education, shaped by the interests of society and students, and aiming to provide an engaging, enlightening and empowering educational experience, would we start from where we are? On the one hand, yes: we would do well to start with the rich legacy of formal quality and compliance systems. We would see to continue the exchange of ideas between experts and learners and maintain the status of graduates. However, in another sense, the answer is no. We would not necessarily choose to start with a system designed around attendance and physical proximity, which come at a considerable cost and constrain supply – particularly where physical proximity is not necessary for education to take place.

Ultimately, though, when it comes to starting place we have little choice. We must start from where we are. As discussed, the problem isn’t with the core elements of accredited qualifications, valid learning outcomes, quality criteria or the fact of assessment. The problem is that, fatally, most universities are hardwired to facilitate a form of education that is generally2 already unsustainable in terms of public expenditure. As this chapter’s epigraph from Laurillard indicates, we have known for well over a decade how technology might utterly transform our models of higher education. In the intervening years, we have also learned a lot about ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 On Learning and Formal Education

- 3 Models of University Education

- 4 The Digital Distance Education (DDE) Model

- 5 Module Narratives

- 6 Teaching Roles

- 7 Module Development: Context, Direction and Practice

- 8 Operating Models and Organisational Change

- Appendix: Am I Ready for Distance Learning?

- Index