![]()

1

Introduction to Gapology

The Concept of “Gapology”

This work will investigate the “gapology” of American politics. Gapology, simply put, is the study of political “gaps,” or divides. Though the concept of gapology can be used to denote the differences between viewpoints (e.g., liberal or conservative) and situations (e.g., married or single), my focus will be the study of marked political disparities between groups (e.g., male or female) in the United States.

One’s demographic background has the potential to greatly influence how one views politics and behaves politically. As such, this book will examine the political beliefs and behavior of different demographic groups in the United States. By studying American political culture from a demographic perspective, I will endeavor to come to a greater understanding of how Americans conceptualize the political universe. How are different demographic groups politically distinct in American democracy? Why are they distinct?

Americans are divided on a wide array of political divisions that go beyond the “red” (Republican or conservative) and “blue” (Democratic or liberal) state classification that has become so ingrained in popular discourse. Media coverage has disproportionately focused on the red state versus blue state divide, leaving the impression that American political behavior is determined by place or residence. This, however, ignores the numerous other divides in American political behavior. What it means to be red or blue is much more complex than geography. There are considerable demographic political divisions—what I will refer to as gaps—that differentiate red America from blue America. The many political gaps in the United States distinguish the political behavior of Americans and are extremely useful in understanding the political divides within the United States today.

The central mantra of this book is that the gaps in American political behavior are not only intrinsically fascinating but also informative. People unquestionably respond to gaps. Americans perceive themselves as belonging to one group or another, and there is widespread acknowledgment that these group memberships affect political beliefs and voting choices. The focus of gapology is on the demographics of the American polity.

There are certainly factors other than demographics that influence one’s political beliefs; partisan identification and ideology are obvious factors that have independent effects on political behavior. Compared with other countries, however, political activism in the United States has often been built more around group identities and less around broad ideologies.1 As a result, group identities have a significant impact on one’s political beliefs. A key principle behind studying gapology is that political attributes such as one’s partisan identification and ideology are influenced considerably by demographics. Americans’ “left” and “right” self-identifications, in fact, are usually symbolic, attached to group loyalties.2 Though gaps represent oversimplifications of the complex reality of political behavior, the utility of gapology is that it connects something of undeniable importance with key characteristics of everyday life.3

Gapology assumes the importance of socialization in determining Americans’ political views. Group differences are a product of shared experiences, which vary considerably from group to group. People do not learn about politics in a vacuum; political behavior is learned through the process of political socialization. The learning of specific orientations to politics and experience with the political system are extremely important in understanding one’s political beliefs.4

By the time one enters college, one’s partisanship tends to be rather stable.5 Party identities are quite stable relative to attitudes, in part because partisans defend their identities by adopting “lesser of two evils” justifications.6 Children acquire partisan attachments through early socialization and develop emotional attachments to a party, even though they may not be aware of any conflict between their party identification and their positions on various issues. One’s family plays the most critical role in the fixing of attachments to political parties and on beliefs on issues.7 Based on the nature of relationships with their parents, children begin developing value orientations at a very early age, understanding morality either as strength and discipline or as compassion for the less strong. Offspring of families with high levels of political interest also tend toward a higher degree of psychological involvement in politics.8

Though political orientations typically begin to form in childhood— shaped through one’s socialization environment, genetics, and development of personality traits—political attitudes can be transformed when public policies directly affect citizens’ lives. Victims of crime, for example, participate in politics more than comparable nonvictims.9 The Vietnam War draft lottery reoriented the political views of young men who received a lottery number. Males holding low lottery numbers became more antiwar, more liberal, and more Democratic in their voting compared to those with high numbers, which protected them from the draft. Low-number young men were also more likely than those with safe numbers to abandon the party identification they had held as teenagers. Vulnerability to being drafted not only structured attitudes toward the Vietnam War, but also provoked a cascade of changes in basic partisan, ideological, and issue attitudes.10

From the perspective of gapology, political socialization is most important in regard to group membership. The idea of a group influencing its members could seem contradictory. A group, after all, is only the sum of its individual members. Yet groups affect the individuals in them. The reality of a group can be psychological, and that reality can change behavior. In the course of a campaign, for example, there may be talk of the “black vote,” “women vote,” “youth vote,” and so forth. These groups are not obviously political: they did not come into being as a result of politics.11 Yet the group shapes the politics of its members because they psychologically identify with that group.12

Social groups help voters organize the political world, and social networks moderate the effect of elite discourse on public opinion.13 People use mental shortcuts to make sense of things, including politics, about which they have limited information. Politically significant group identities are widespread among Americans, and group members’ policy preferences cut across generations. Similarities in life experiences lead to similarities in political outlook.

People who conceptualize politics from a group-benefit perspective tend to be abstract in their evaluations and in the substantive content of the criteria they employ. They evaluate candidates and parties in terms of their sympathy and hostility toward particular groups in society.14 Some members are very attached to a group, others less so. Although everyone may be in the group in name, certain members will be strongly pulled by the group, while others may actually feel nothing for the group. Thus, even though all members carry the same group label, they can differ substantially in their psychological attachment to it. The more identified one is with the group, the closer one will adhere to the group norm.15 As a result, those who identify strongly with a particular group are more likely to be affected politically by that group membership.16

Americans increasingly identify with various social groups as opposed to political parties.17 Yet even though Americans are more likely than they were to identify themselves as Independent as opposed to Republican or Democratic, party loyalty today is much higher than it was thirty years ago, especially among Democrats.18 Most Americans, of course, are not formal members of a political party. But they do feel some psychological affiliation to a party, and that strongly shapes their political behavior. Official party activists compose a very small group, but the group that is psychologically attached to a party is large.19 The primary motivation for voting today, in fact, is partisanship, not civic duty as it had been in the past. As partisanship has increased, Americans have become more political, as they are more likely than before to talk to their friends and neighbors about politics and display yard signs and bumper stickers, while also donating money to the parties and candidates in record numbers.20 This reinforces the importance of group membership.

Gapology relies on the idea that political culture—the predominant pattern of ideas, assumptions, and emotions regarding political processes—shapes the socialization experiences of groups, which in turn leads them to have different political belief systems. Differences in societal experiences alter citizens’ cultural orientations.21 Political culture exercises a psychological grip that contributes in important ways to the well-being of a relevant group.22 It is a common mistake to try to explain the diversity of everyday behavior in the United States on the grounds of uniformity in shared national values. Even though the United States is a single nation, Americans do not constitute a single political culture.23

The United States in Red and Blue

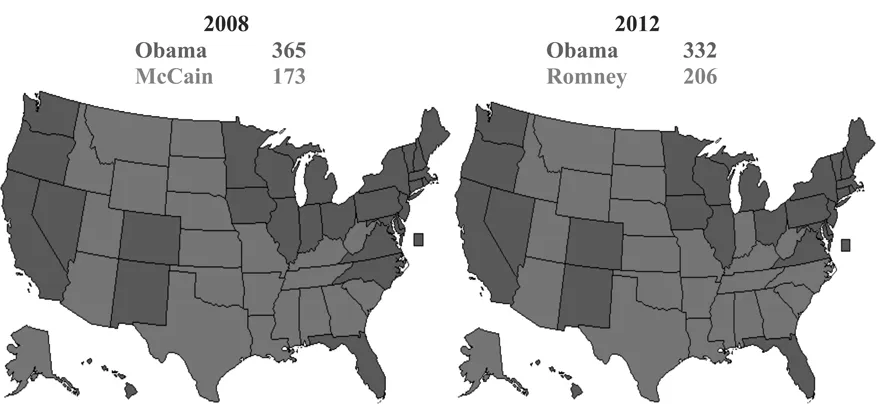

Since 2000 presidential election-night media coverage has been dominated by the coloring of each state red or blue depending on which party’s candidate carries that state’s electoral votes. Blue states where the Democratic Party is dominant include those in New England (such as Massachusetts), the Northeast (New York), the Midwest (Illinois), and the West Coast (California). The strongest red states tend to be located in the South (such as Alabama), the Great Plains (Nebraska), and the Mountain West (Utah). This red-blue color scheme for differentiating Republican and Democratic support is relatively new. Historically, the use of colors to indicate partisan support was arbitrary. Time magazine, for example, favored Democratic red and Republican white in the 1976 election between Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford and then later reversed those colors for Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter in 1980. Gradually, the color scheme became more formalized, but it was not until 2000 that red for Republican and blue for Democrat became the standard. The red state–blue state dichotomy has now become entrenched in the political lexicon.24 Figure 1-1 displays the Electoral College maps for the 2008 and 2012 elections in light gray (often shown in red, where the Republican nominee for president won the state) and in dark gray (often shown in blue, where the Democratic nominee won the state). These maps—that is, the actual Electoral College vote count—will be used as a baseline when I discuss hypothetical Electoral College maps for specific demographic groups in Chapters 2 through 7.

FIGURE 1-1 Electoral College Maps of 2008 and 2012 Presidential Votes

Source: National Election Pool exit polls, 2008 and 2012.

The increasing political polarization in America along a red-blue divide is partially the result of a greater media emphasis on cultural issues and resulting cultural divisions. Findings suggest a widening and deepening of a cultural-values-based realignment of the American electorate. For red America, moral traditionalism has exerted a stronger influence on vote choice through party identification; more morally traditional citizens have become more Republican. The growing importance of values and the cultural divide has served to nationalize citizen’s vote choices, with voters more willing to cast their ballots in state and local elections on the basis of national issues that usually are only thought to affect presidential vote choice.

The gaps on cultural issues are in part the result of the fact that Americans have become increasingly divided along religious lines. Religious polarization is associated with a growing schism on cultural issues, especially abortion and gay marriage. The religious cleavage between the parties has grown over time as the Republican Party has become more traditionally religious and the Democratic Party more secular. The more often one attends religious services, the more likely one is to vote Republican, and this so-called god gap is growing (I will analyze this in detail in Chapter 3).

This has not always been the case. In 1960, for example, regular churchgoers were actually more Democratic in their vote for president.25 Today, committed evangelicals, who have distinct political ...