![]()

1 Introduction

The modern-day office depends upon human interaction and – more importantly – engagement. Communication technology might allow us to work from anywhere but face-to-face interaction still plays a vital part in organisations. Presented with so many options about where we work, how do we make the office the place of choice?

Discussions about ‘relationship chemistry’ bombard us daily in popular media. Relationship chemistry describes a bundle of emotions that two people get when they have a special connection. It is the impulse that makes you feel, “I would like to see this person again.” How often do office environments give us the same feeling – that we are able to ‘click’ with it? Can designers and facilities managers play some role in creating this elusive chemistry? This book explores the untapped potential of workspaces that we occupy, spaces in which we spend an increasing proportion of our waking day.

Good chemistry is not just about person-to-person relationships between two people. The growing importance of collaborative working has redoubled our attempts to understand exactly what makes teams tick. Group interaction is only possible if the chemistry is right. One leading organisation, Deloitte, has developed its own business team entitled Business Chemistry with the express intent of improving the art of relationships. And when it comes to solitary undisturbed working environments, the chemistry between the office worker and their environment becomes pivotal. The emergence of ‘deep working’ (Newport, 2016) in people’s work routine necessitates a very different workspace. How do we get the chemistry right and meet these very different workspace needs?

Some of the characteristics of good chemistry in a relationship include non-judgement, mystery, attraction, mutual trust and effortless communication. How often do we encounter this type of relationship in our work environment? Wouldn’t it be special if the office environment itself encouraged a sense of mystery, attraction, mutual trust and effortless communication? Interior lighting, space planning, user control, colour schemes and thermal comfort are just some of the design considerations that have been shown to influence individual and group behaviour. More often than not, studies focus on the ‘cognitive’ and ‘behavioural’ interaction between office workers and their environment. But what about emotion (and the related concepts of affect or feeling)? A growing number of organisations now recognise just how much they have neglected the ‘A’ in the ABC of psychology (affect, behaviour and cognition). In a world where loyalty and belonging have become a rare commodity, organisations are reaching out for ways to create a ‘trust-based’ culture. Millennials, unlike their predecessors, have grown up in an era where the ‘contract’ is king. They have become accustomed to fixed-length contracts and are more inclined to switch between employers. The office environment has become one of the few ways to attract and retain this talent.

Figure 1.1 Office chemistry.

Leveraging the power of emotion

So what exactly is an ‘emotionally intelligent’ workspace? In some ways it runs counter to the idea of an ‘intelligent building’. Whilst the intelligent building attempts to leverage the power of technology, the emotionally intelligent building attempts to leverage the power of human emotion. In the business world, personal intelligence is no longer seen as the main indicator of job performance. A much better predictor appears to be ‘emotional intelligence’:

Emotional intelligence can be defined as the ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior.

(Colman 2015)

What part does technology play in all of this? One might imagine a science-fiction scenario whereby the building itself is able to monitor the emotions of its occupants and perhaps use this information to guide its own behaviour. There are indeed examples discussed in this book that illustrate this possibility and the ethical implications. But building technology has not always been supportive of human emotion. Indeed, what has been considered as building intelligence can undermine emotional intelligence. In the pursuit of a seamless network of computer and human interfaces, we can end up with an office environment that is entirely process driven. The office as a knowledge exchange is thus measured only in terms of connectedness.

At the other extreme, prestige office buildings can sell themselves in terms of luxury, delight and novelty. Such buildings have proven to be effective at enticing new employees. Rather than using the appeal of new technology, such buildings rely on the experiential aspects of natural light, space and furnishings. Undoubtedly these buildings provide the opportunity to engage with people’s emotions. But it seems that this is often arrived at by chance or design hunches. What we want to do in this book is create a framework that uses an evidence-based approach to emotional intelligence. In other words, is it possible to design and operate a building that is sensitive to the emotional needs of its occupants? This is not about pandering to whims. It is about supporting the relationship chemistry that is becoming so important to successful organisations.

What do we mean by emotional intelligence?

Intelligence is overrated. That is what the evidence has shown us. Whilst there is much debate over what intelligence actually is, we consistently find that, however you measure it, it is a very poor predictor of personal success and happiness. This applies whether we are looking at our effectiveness in business or in our personal relationships. Yet there remains an unquestioning reverence for the technology-laden ‘intelligent building’ or the ‘smart building’.

In just the same way that we measure personal intelligence using IQ, practitioners have attempted to assess a building’s IQ. Early formulations of the intelligent building in the 1980s and ’90s saw increasingly complex but dedicated systems for energy management, lighting control, air-conditioning systems and other self-contained building technologies. Moving into the new millennium we witnessed the complete integration of these systems using complex building management systems. Whilst these advances improved the efficiency of the building, their impact on building users was more subtle. Undoubtedly the intelligent building has enabled office users to engage almost seamlessly with computers and other workers. The advent of universal Wi-Fi in the workplace has allowed entire workforces to become truly mobile. It is now possible to have an uninterrupted transition between the office, home or anywhere else. Furthermore, the ability to track and monitor user behaviour gives us an unprecedented understanding of how a building performs.

Despite these new advances, the modern office faces more challenges than ever. Some commentators have predicted the demise of the office. Office designers and facilities managers have had to do a rethink. What is it that an office provides that a home working environment seems unable to fulfil? Organisations demand workplaces that are more than comfortable desks set up with the latest kit. Offices need to become indispensable parts of an organisation: places of choice where trust and loyalty are nurtured.

Perhaps we have exhausted the idea of the intelligent building? Or perhaps in our pursuit of building intelligence we have neglected something. In this book we argue that the modern workplace needs an entirely different kind of intelligence: emotional intelligence. In just the same way that emotional intelligence (EQ) has proven to be a much better predictor of success at work and in people’s personal life, the equivalent measure could be used to identify emotionally intelligent buildings. We might try to assess a building’s capacity to match the emotional needs of groups and individuals in the workplace. But let’s not get hung up on bean counting. More than anything, we need to ‘frame’ the problem that is in front of us: how to harness human potential.

Is this about technology? Whether you are an architect, facilities manager or indeed any professional involved in leveraging human potential through the built environment, you are in the business of emotional intelligence in all its forms. Emotional intelligence can be thought of as the ability to:

• recognise, understand and manage our own emotions

• recognise, understand and influence the emotions of others.

We might have some difficulty imagining a building that can recognise and understand its own emotions (unless of course you are a science-fiction enthusiast). However, the second item, ‘being able to understand and influence the emotions of others’ clearly has relevance to workplace design. Isn’t it something that architects and interior designers do all the time? Indeed, lighting, fixtures and fittings, colour schemes and soundscapes are devices that are routinely used to create ambience. But is this emotional intelligence? Is it enough to simply create the desired emotional setting? What level of user control should there be? What about influencing emotions in a shared environment? If a building cannot recognise emotions, can we say that it is capable of influencing our emotions?

Resorting to headphones

Zhi has always adopted an ‘open-door’ policy working as a senior partner in her organisation. Recently her organisation has moved to an open plan hot-desking work environment. She can no longer express her open-door policy because they have taken the door away and the walls as well. In fact, sometimes she would like to have a ‘closed-door’ policy, but without a door she has had to resort to using headphones.

Zhi’s predicament is perhaps a rather simplistic illustration of how we use the physical environment to express emotions. Take away a key part of that setting and suddenly we feel rather exposed. Workplace designers have been busy removing fixtures and fittings that we rely on to convey emotions. The ‘non-stick’ environment eradicates ‘emotional potential’. In our attempts to create the intelligent building, we thwart the emotionally intelligent building.

Throughout this book we examine the devices and interventions that might be used to enhance emotional intelligence. As much as possible, the analysis is through the ‘emotionally intelligent’ lens. Rather than parading a set of interesting possibilities, the book attempts to develop a framework to capture the emotional response of building users. It presents an ‘emotionally intelligent’ language to enable diverse design teams to share a common understanding.

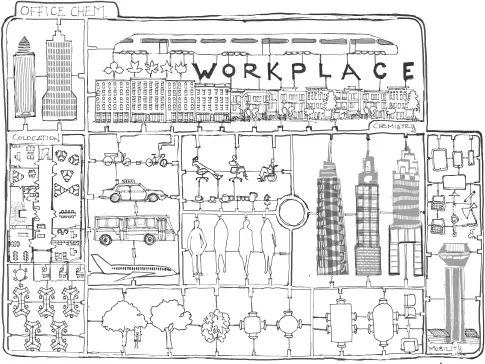

Can a building really be emotional? To answer this question, let’s first of all look at the modern-day office – an example of a complex and layered system. In order to work, it demands the close integration of a physical system, an IT infrastructure and people (the facilities management team). But the physical system is itself composed of different elements of varying lifecycles. Instead of just bricks and mortar, the contemporary workplace is comprised of ‘shell, services and sets’. This layered approach identified by Duffy conveys how the modern office enables technological and organisational change:

Our basic argument is that there isn’t any such thing as a building. A building properly conceived is several layers of longevity of built components.

(Duffy 1990, p. 17)

Whilst the shell or building structure remains relatively unchanged, changes to building services typically occur every 10 to 15 years as fit-outs respond to the changing demands of clients. Rates of change are even more dramatic when we look at the furniture and fittings (sets) to be found in today’s office. This innermost layer of the office ‘kit of parts’ represents a progressively large constituent, capable of meeting both human and IT demands. It is this soft, fluid layer that can undergo changes almost on a daily basis. This level of orchestration relies on the interventions of people – both users and, where necessary, the facilities management team. In reality, the modern office is far from being a static monolith: it is a living system. Adaptability is driven by human needs rather than technological needs. It is this capacity to accommodate changing human needs that defines the emotionally intelligent building.

Figure 1.2 A front-of-house corporate setting.

Feelings or emotions?

Isn’t the modern work environment about rational thought and behaviour? Don’t emotions simply get in the way of rational decision-making? This has remained the long-standing belief of many organisations and management theorists. But a growing number of practitioners now acknowledge the pivotal contribution of emotions in organisations. There is an emerging realisation that the physical environment can be used to manage emotions and improve work outcomes.

If you are a psychologist, you’ll often refer to feeling or emotion as an affect. It comes first in the ABC of psychology (affect, behaviour, cognition). It’s a psycho-physiological construct. Put another way, it hits you in the heart as well as the mind. It’s not just about feelings – we can actuall...