![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Franc Chamberlain and Ralph Yarrow

This volume does not set out to review the effects of Jacques Lecoq's teaching everywhere. His school has been in operation for over forty years and companies of ex-students have flourished around the world. In focusing on the influence of his work in Britain, the essays here however inevitably bring out key features of his approach which are relevant to performers and companies everywhere; they raise questions about the relationship of his pedagogy to drama training and about the ways in which performers, companies, directors, writers/devisers and audiences who have experienced the work incorporate it into their practices and expectations and thus contribute to changing the nature of theatre.

In what follows immediately, Franc Chamberlain sets out some personal parameters to the encounter with Lecoq on the British theatre scene. This is followed by a summary of the approaches of the essays in this volume which places them in other contextual frames.

From the Bakery to the National

In the autumn of 1974 I was working a Friday-night shift at a bakery whilst studying for my A-levels. My local Little Theatre, The Loft in Leamington Spa, was hosting a weekend mime workshop with Geoffrey Buckley.1 I remember turning up on the Saturday morning straight from work wearing a black surplus National Fire Service greatcoat, covered in acne, with my skin feeling an unpleasant mixture of grease and flour. My eyelids felt as though they had flour underneath them, which they probably did. My memory of my arrival is still quite strong because I always felt slightly out of place in the theatre and felt particularly self-conscious about my appearance having not slept since the Thursday night. I think I remember someone commenting on my commitment …

It was during this workshop that I first heard the name Jacques Lecoq. Because Buckley focused on pantomime blanche during the weekend, however, Lecoq's name became equated in my mind with Marceau-type images of imaginary staircases, windows, invisible barriers and so on. Buckley's performance on the Sunday evening involved him attempting to speak to the audience but being prevented from being heard by an imaginary glass barrier, like an invisible safety curtain. He would struggle to lift the obstacle, succeed, try to speak, and immediately discover another invisible wall. In my memory he did eventually speak to the audience – an act which immediately differentiated his work from that of Marceau.

I don't remember hearing of Lecoq's name again until eight or nine years later when I attended another weekend workshop with Buckley in the same room at the same theatre. Lecoq was a mysterious figure for me, someone with whom it was possible to study if you had the money – I didn't.

I developed a stronger interest in Lecoq's work from 1984 when, as a mature student studying for a BA in drama at the University of East Anglia, I was asked to cover the Norwich Mime Festival for the student paper Phoenix. Between 1984 and 1989 I covered the Festival for both Phoenix and City Wise, a local arts magazine and attended workshops and residencies with a host of Lecoq graduates including Theatre de Complicité, Mark Saunders, I Gelati, Justin Case, John Martin, and Clive Mendus.2 I also taped interviews with Marcello Magni and Simon McBurney of Complicité, Clive Mendus, and Footsbarn. It was during the interview with McBurney and Magni in February 1984 that I think I first heard the term physical theatre in relation to Lecoq, a term which I was to use but become uncomfortable with in the late 1980s after watching Ben Keaton's Memoirs of an Irish Taxidermist (if this is physical theatre, I thought, then what isn't?). I didn't attend Lecoq's master class in 1988 which is a key moment in the formation of the perception of Lecoq-based work in this country. I was, however, applying what I'd learned with a company I'd formed with Dominic Everett in 1986 (Hidden Risk which was later to include sometime Footsbarn members Barry Jones and Mafalda da Camara) in performances and workshops. My work during this period wasn't solely Lecoq based, however, and I drew on a number of other sources and teachers. Any attempt to assess the influence of Lecoq on the British theatre needs to take into account experiences like my own–people who have worked with Lecoq graduates, knowingly or unknowingly, incorporated the exercises, methods, and aesthetics into their own work and then passed them on to others. Such a pattern of influences, which has been growing since 1968 at least, eventually becomes impossible to trace with any certainty back to Lecoq. Perhaps in these cases we should no longer be talking about ‘influence’, maybe, as Eric Bentley suggested it is a blanket term which ‘covers far too large a bed’3:

When Jesus appeared in the sky and said, ‘Why persecutest thou me?’ Saul of Tarsus, a Christian-baiter, became the Christian saint, Paul. That's influence: impact unmistakable and total …

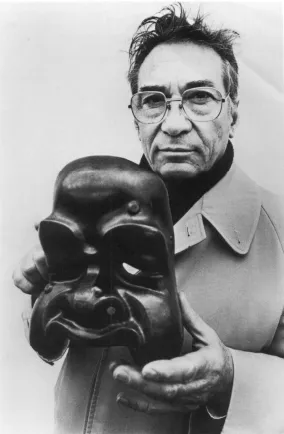

Jacques Lecoq: “Tout Bouge” (“Everything Moves”), London International Workshop Centre, Queen Elizabeth Hall, South Bank Centre, 1988. Photo: Coneyl Jay

Lecoq's ‘influence’ on the British theatre, if it can be called that, consists not in the adoption of a significant body of theory by critics and practitioners, nor in the visit by a company which exemplifies the ‘authentic’ Lecoqian theatre in the way in which the visit of the Berliner Ensemble (to London of course) in August 1956 is seen as an ‘authentic’ exemplar of Brechtian theatre which had a direct influence on subsequent developments within the British Theatre. (Recent visits by Barba's Odin Teatret and The Gardzienice Theatre Association are having an influence in different sections of the British Theatre but, as with the Berliner Ensemble there is a single ensemble connected to a specific guru figure). There is no Lecoq equivalent of Helene Weigel's Mother Courage or Ryszard Cieslak's Constant Prince or Roberta Carreri's Judith. There is no ensemble with whom Lecoq is uniquely associated, no performer who is the Lecoq disciple par excellence. Lecoq offers a method of working, what the students do with it is up to them. He doesn't direct them. He doesn't tell them what to say. Lecoq's school is, as Simon McBurney put it in an interview with me in 1985, ‘a school to provoke the imagination; to provoke creativity in the actor so that he is not just another consumable product’. Lecoq's work cannot be ‘diluted’ or ‘polluted’ by graduates developing it in their own way, there is no pure Lecoq form and, although there are companies made up solely of Lecoq graduates, graduates are just as likely to find themselves placed with other fringe companies or, given the high profile of Théâtre de Complicité, within the British theatrical mainstream. Whilst Lecoq's influence on individuals may be direct and transformative, the influences of his graduates on the British theatre are more diffuse. Perhaps this explains why Lecoq's name is absent or only briefly alluded to in contemporary studies of British Theatre.4

On the other hand, Lecoq's emphasis on provoking the actor's imagination and creativity is a means of freeing actors from the ‘tyranny of the text’ in order to create their own scenarios. Whilst this is in a tradition of theatrical experimentation and devising which derives from, inter alia, Copeau, Stanislavski, Craig, and Artaud most theatre criticism in Britain still focuses on the written text and views devised theatre as somehow inferior. John Elsom in his entry on theatre in the United Kingdom for The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Europe (1994) acknowledges that there have been numerous projects which have attempted to do without a writer, but claims that British theatre is still writer-dominated and thus leaves non-text based theatre unexplored. An encyclopedia entry is necessarily restricted in scope and an overview is perhaps not the place for an investigation of the notion of ‘authorship’. This question is also left unaddressed by a volume of essays entitled The Death of the Playwright? (Ed. Adrian Page 1992) where the notion of the author as individual genius and guarantor of the meanings of a play is subject to investigation but the whole notion of a group of performers devising a piece is left unexplored. Part of the problem rests with the difficulties in documenting devised performances5 but there is little difference between a text which has an unwritten physical and vocal score and a piece of dance in these terms.

Interestingly, despite more than forty years of teaching an international clientele, Lecoq is only mentioned in the French entry to the World Encyclopedia in the sections on Dance Theatre and training. The latter mention merely mentions the existence of the school in Paris, whereas the former entry describes him as a ‘mime’ who ‘later discovered masks’.6 This indicates that the problem of assessing Lecoq's work isn't a purely British one.

The emphasis on the importance of literature for the theatre can be seen in the extent to which Theatre de Complicité have become a force in the British Theatre once they began, firstly to deal with ‘classic’ playtexts – The Visit (1989) The Winter's Tale (1992) The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1997) – and secondly, to adapt literary classics for the stage – The Street of Crocodiles (1993) Out of a House Walked a Man (1994–5) Foe (1996). Complicité will go down in British Theatre history for these productions rather than the earlier non text-based pieces such as A Minute Too Late (1984) or More Bigger Snacks Now! (1985). Admittedly the second of these doesn't particularly deserve to be remembered although this, I would suggest, has less to do with the ‘inferior’ quality of the material and more to do with the overall structure of the piece. But this has to be weighed against the dreariness of Out of a House Walked a Man and, particularly, Foe, a production which saw the betrayal of (almost) everything that had made Complicité exciting in the past. More recent productions have stayed with staging plays such as The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1997) at the Royal National Theatre and Ionesco's The Chairs (1998) with mixed results. Leaving aside questions of the aesthetic failure or otherwise of Complicité’s recent work, the emphasis on the classics effectively works to keep theatre in its place as a branch of literature.7 This is ironic when we consider the emphasis which Lecoq places on the body of the performer and the need for each individual to find something to say

There is, of course, no reason why Lecoq graduates shouldn't work with texts. Being freed from the tyranny of the text is not the same as abandoning the text altogether; if it were then we would be returning to the days of the silent mime. The work of Steven Berkoff is an important example of a Lecoq-derived physical theatre which re-thinks the use of text in a creative way. Berkoff doesn't just add speech to a physical style but reaches for a vocal and linguistic complement. I'm wanting to point out some of the pressures which are placed on companies within the British Theatre to reinforce the importance of text. Perhaps this emphasis on theatre equals text is why dance companies such as DV8, who have picked up the label ‘physical theatre’ to indicate a break from the traditions of contemporary dance, appear to have fewer problems with the British critical establishment; dancers aren't expected to base their work on pre-existent literary texts. Furthermore, DV8 are more likely to be discussed by dance critics rather than the drama critics who prefer text.

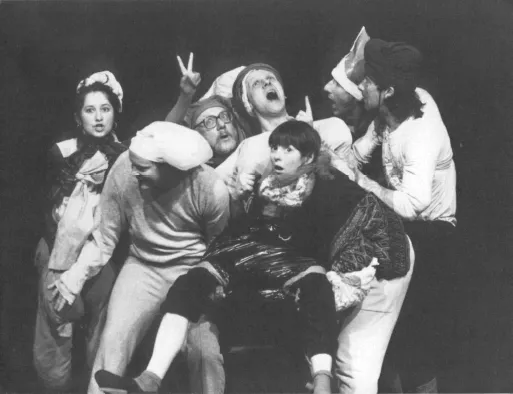

Students explore the world of the buffoon under the direction of Jacques Lecoq, London International Workshop Festival, 1988. Photo: Simon Annand.

The introduction of DV8 into the debate also draws attention to the work of other companies exploring the boundaries of dance and theatre such as Frantic Assembly and Volcano. This latter company, however, have based their performances on pre-existing texts from Shakespeare's sonnets (L. O. V. E (1993)) and The Communist Manifesto (Manifesto (1994)) to the plays of Ibsen (Ibsenities: How to Live (1994))and Chekhov (Vagina Dentata (1996)). The texts in Volcano's productions are exploded and phrases are used as elements in a vocal choreography. The company have not managed to develop their work effectively since Ibsenities, however, and the two most recent productions Under Milk Wood (1996) and The Message (1997) suggest that the company has lost its way. (Interestingly, Under Milk Wood fell foul of the Dylan Thomas estate and had to cease touring: a spectral authority exerting textual compliance.) Whilst DV8 was founded in 19868 by Lloyd Newson, a former member of Extemporary Dance, and thus has no clear link to the work of Lecoq, the company was formed out of a desire to enable the development of the dancer as a creative artist with something to say. To suggest that there might he a hidden influence from Lecoq on DV8’s work would be stretching an idea too far, especially as the emphasis on the dancer having ‘something to say’ has been an important part of Pina Bausch's work with the Wuppertal Tanztheater since the 1970s. There is, however, a wider cultural connection which owes something to the radical political and social movements of the 1960s and 1970s whilst the linking back to anti-textual developments and to calls for a return to the body in theatrical modernism which hark back to Romantic celebrations of creativity.

Writing in 1908, in The Actor and the Übermarionnette’ Edward Gordon Craig identified the need for a rigorous physical training of the actor which would include the use of mask, argued that the actor, by virtue of being human would ‘revolt against being made a slave or medium for the expression of another's thoughts’, and indicated the importance of creativity:

I see a loop-hole by which in time the actors can escape from the bondage they are in. They must create for themselves a new form of acting […] Today they impersonate and interpret; tomorrow they must represent and interpret; and the third day they must create. By this means style may return.”9

Whilst Craig recognised the importance of a physical training akin to dance, of developing as a creative rather than as an interpretative artist and thus freeing the actor (and the theatre) from the tyranny of the text, he was taken to task by Jacques Copeau for failing to take on board the responsibility for training such performers.10 Copeau was, in turn, criticised by Craig for being a ‘man of literature’ rather than a man of the theatre. Nonetheless, it was Copeau rather than Craig who created a school which focused on the physicality and creativity of the actor and who was to contribute, through his student and son-in-law Jean Dasté, to the early theatre training of Jacques Lecoq.11 Lecoq himself, however, claims that when he began doing theatre he had ‘never heard of Copeau’ (see the essay by John Wright in this ...