- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This accessible volume provides a brief introduction to the institutions, policy concerns, and international roles of the Pacific islands. Evelyn Colbert expertly paints an overall picture of the region using broad brush strokes, complementing the mostly specialized literature available about the South Pacific.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Pacific Islands by Evelyn Colbert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Politique asiatique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Region and Its Peoples

Ten thousand islands—a few large, most very small, many uninhabited—are scattered over a vast oceanic expanse, stretching from the southern reaches of the Pacific to the Tropic of Cancer and covering 20 million square miles. The inhabitants of the islands, some 6 million people, see themselves in a unique relationship to their surrounding waters, one that distinguishes them in all their diversity as Pacific peoples.

Convention assigns the islands to a still larger region, Oceania, which includes Australia, New Zealand, and even Hawaii, whose claim to membership is based on its location, insular character, and the ethnic identity of its indigenous people. For the islands, however, Oceania is little more than a useful political device. It casts the much larger and more developed Australia and New Zealand as partners rather than patrons, while encouraging them to provide aid and protection. The inclusion of Hawaii reinforces island claims to U.S. attention.

Rhetorical concepts of an even more comprehensive Pacific grouping—whether the “Asia-Pacific Community,” the “Pacific Basin,” or the “Pacific Rim”—have had little resonance throughout the islands. Although anthropologists hold migration from Southeast Asia responsible for the original peopling of some of the islands, today’s islanders, settled for millennia in their present homes, see little kinship between themselves and Asians, including those who have more recently taken up residence in their midst. Conversely, those outside the region who speak eloquently of a dawning Pacific century rarely have these small islands in mind.

In the everyday world, the islands command little attention. Deficient in most elements of global importance, whether economic, political, or military, they are also uniquely distant from the centers of international power and interest. In contrast, they have an unmatched aura in the world of the imagination. The Western image of Paradise on earth, originating from the accounts of eighteenth-century explorers, was perpetuated in the nineteenth century by writers and artists Paul Gauguin, Pierre Loti, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Herman Melville, among others. Today’s tourist industry emphasizes the survival of this idyll, while journalists and social critics point accusingly to its demise under the impact of Western materialism.

Once under colonial rule, this thinly populated region is today the site of an extraordinary number and variety of mostly sovereign individual polities. Distance between island groups, different cultural characteristics and colonial histories, and the small scale and localism of precolonial societies have all been factors in creating this array. The 14 independent states form the largest group of political entities. They include Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Western Samoa, as well as five freely associated states—the Cook Islands and Niue with New Zealand and the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Palau (Belau) with the United States.

The transformation from dependency to independence, in the Pacific islands as elsewhere, was a post-World War II phenomenon. However, decolonization began later than elsewhere and left more remnants of empire. These remants include the French territories of New Caledonia, French Polynesia, and Wallis and Futuna; the New Zealand territory of Tokelau; Chile’s dependency, Easter Island; and, under the U.S. flag, the territories of Guam and American Samoa and the commonwealth of the Northern Marianas. Although these various dependencies are more fully self-governing than the typical colony of the age of imperialism, they lack essential elements of sovereignty and, in some cases, are still seeking changes in their status. Also remaining under Western sovereignty—U.S., Australian, or British—are islands that are minuscule in area and population even by South Pacific standards; for example, Britain’s Pitcairn Island has a land area of 4.5 square kilometers and a population of 53, descendants of the Bounty mutineers.

Within the parameters of small size and dependency, the island polities vary widely in size, physical characteristics, and the number of islands that fall under their authority. The jurisdiction of some extends over hundreds of often widely dispersed islands; those of Kiribati, for example, are scattered over a distance equal to that between the eastern and western coasts of the United States. The jurisdiction of others extends over only one or two islands. In most island polities, whether compact or spread out, a substantial percentage of the population is clustered in and around a major urban center. Some island polities are the most mini of ministates. Only Papua New Guinea is large by global as well as local standards; occupying some 80 percent of the region’s total land area, it is considerably larger than the United Kingdom or the Philippines. Papua New Guinea is the only country in the region that shares a land border with another state. As a legacy of the colonial era, the western half of the island of New Guinea, once part of the Netherlands East Indies, has been absorbed into Indonesia as the province of Irian Jaya.

Except in Fiji, Guam, and New Caledonia, the islands’ inhabitants are mainly indigenous or migrants from elsewhere in the South Pacific. In Fiji, as of 1993, indigenes constituted only half of the population; for many years, they were outnumbered by Indians, mostly descendants of imported laborers, who now constitute 44.8 percent of the population. In Guam, only 42 percent of the population claims at least partial descent from the indigenous inhabitants, the Chamorro; Filipinos at 24 percent are the next largest group. In New Caledonia, the indigenous Kanaks make up only 43 percent of the population; the Caldoche, persons of European (mostly French) stock, constitute 38 percent; and Polynesians and Asians make up most of the remainder. In Fiji and French Polynesia, although citizens of European and mixed blood are not numerous, their communities are important: in Fiji because they mostly align themselves with the Fijians; in French Polynesia because of the prominence of the so-called demis in government and business.

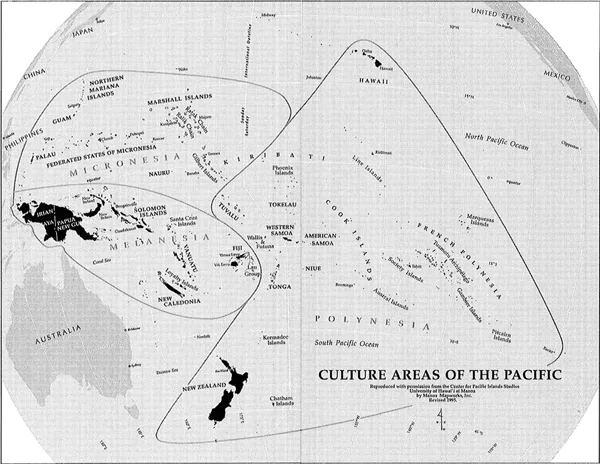

Convention divides the indigenous peoples of the islands into three groupings: Polynesians, Melanesians, and Micronesians (see Figure 1.1). When explorers first used these terms they were primarily geographic categories: many islands, black islands, and tiny islands. However, they were soon applied to the different cultural characteristics of the peoples. As the study of island societies has progressed, many past generalizations and sharp distinctions have been challenged; in the words of the eminent Australian scholar Roger Keesing, these designations have come to have “somewhat ambiguous edges.”1 Nevertheless, they are designators with which the islanders have come to identify themselves and by which they are known to others, their oversimplifications and wholly European terminological origins notwithstanding.

Polynesia includes the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Niue, the two Samoas, Tokelau, Tonga, and Tuvalu as well as Hawaii and New Zealand. There are also long-settled Polynesian pockets in parts of Melanesia. Polynesians are generally tall and of heavy build with skin color dominantly light or reddish brown. The languages of Polynesia are closely related; native speakers of one can quickly become fluent in another. Their traditional societies were highly structured along genealogical lines. The hierarchical order gave great authority to hereditary chiefs and attached to them some of the sacred power (mana) of the gods. But it also required some chiefly responsiveness to the views of those farther down the social ladder and to priestly interpretations of rituals and tabus. Rivalries among chiefs for status and power made for frequent warfare, usually brief and small-scale.

Melanesia includes the largest states of the region—Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands—as well as New Caledonia and Vanuatu. (Irian Jaya also remains dominantly Melanesian.) Fiji is Melanesian with a difference. Although geographically halfway between Melanesia and Polynesia, its chiefly society resembles that of its Polynesian neighbors, Tonga especially, with which it shares close historical links.

In contrast to the relative homogeneity of the far-flung Polynesians, great diversity characterizes the cultures of the less widely dispersed Melanesians. Scholars have attributed the development of shared characteristics in the Polynesian islands to the mobility of their seafaring inhabitants. Melanesians in contrast were disinclined to move outside their typically small-scale sociopolitical kinship units. Today Melanesia’s peoples speak some 1,200 different languages, mostly mutually unintelligible; Melanesian pidgin provides something of a lingua franca for Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. Melanesians also vary greatly in physical type and in skin color, which ranges from light brown to deepest black.

Traditional social organization also differed remarkably among the islands of Melanesia. Generally, however, societies were less stratified than in Polynesia, and lineage was less important in determining status. Thus the Melanesian Big Man achieved his position from his ability to amass a surplus of wealth he could share with his kinship group in the form of feasts and community buildings. Hostility to neighbors outside the kinship group was universal and the source of almost incessant small-scale warfare.

Micronesia is made up of the northernmost of the islands: Nauru, just south of the equator; Kiribati, north and south of the equator; and, north of the equator, Guam, the Northern Marianas, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. Micronesian characteristics are frequently described as falling between those of Polynesia and Melanesia. Like the Polynesians, the Micronesians were traditionally a seafaring people. In fact, they were the preeminent shipbuilders and most skilled and adventurous mariners of the South Pacific. Their traditional social structures, while differing significantly from one island group to the next, were generally hierarchical and based on lineage.

In the traditional societies of all three groupings, great significance was attached to propitiating a multitude of gods and spirits. Competitive giving and elaborate display were important elements in the pursuit of status, and the warrior ethic was held in high esteem. Title to land was vested not in individuals but in kinship groups whose members derived from their common ancestry a variety of obligations to one another. Economic life was village and family based; subsistence agriculture was supplemented by fishing, hunting, gathering, and some trade. With tools of bone, shell, and stone, islanders produced both the necessities of life and ceremonial objects, well suited to their purposes and pleasing to the eye. Into this traditional order, the West began to intrude on a significant scale only toward the end of the eighteenth century.

In the more than two centuries since these first contacts, the Pacific islands have undergone many changes. Some have resulted from the direct effects of the growing Western presence, bringing with it new commodities, forms of production, sources of authority, ideas, and religious beliefs. Others, more indirectly, have reflected changing events in the surrounding world. Empire building before World War II brought the islands into the global political order as dependencies of Western powers and Japan, a status islanders mostly accepted without significant resistance. Empire dissolution in the wake of World War II brought independence, or at least self-government, under political institutions derived from Western models but shaped by the continuing influence of tradition. Democratic institutions, introduced in the decolonization period, have been remarkably durable, despite a wide range of problems that mirror on a small scale those confronting other developing and even advanced countries. Whether sovereign or otherwise, most island polities remain economic dependents of those Western countries whose aid has been essential to compensate for meager resources and geographic isolation and to help meet the needs and expectations of growing populations. Their consciousness of weakness and dependence, however, has encouraged island governments to organize regionally, in order to influence policies pursued by the more powerful that affect island interests or well-being.

Note

1. R.J. May and Hank Nelson, Melanesia: Beyond Diversity (Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1982), Vol. 2, p. 2.

PART ONE

Exploration, Contact, and Control

2

Explorers, Traders, and Missionaries

The great age of European exploration in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had left the island world virtually unknown to the West and undisturbed by Western activity. By the time of the American Revolution, however, a new era of Western exploration had opened in the islands. Explorers, soon followed by traders and missionaries, brought the islands to the attention of a curious and fascinated West and introduced Western ways and goods to equally curious and fascinated islanders. The introduction of new products and technologies altered material culture; island cosmologies rapidly absorbed Christianity; and socioeconomic change and the involvement of Westerners impacted on traditional authority systems.

Explorers

The European explorers who followed Ferdinand Magellan across the Pacific were preoccupied with the search for routes to Asia. As their visits to the South Pacific were few and far between, they remained unaware of the multitude of inhabited islands scattered in its vast waters. Some sixteenth-century Spanish and Portuguese navigators landed in, or at least observed, one or another of the islands. But only in Micronesia was there a lengthy presence, in Guam, the southernmost island of the Marianas chain, which became a way station for the Spanish galleons that sailed from Mexico to Manila loaded with gold and silver for the China trade.

In some respects, these limited sixteenth-century contacts resembled those of later years. Encounters between Europeans and islanders were sometimes friendly but frequently hostile; whichever side initiated violence, Westerners quickly demonstrated the superiority of their firepower. Spaniards in pursuit of their own objectives took sides in tribal struggles. Explorers claimed sovereignty for the Spanish Crown, and missionaries attempted to convert the islanders to Christianity.

Except in Guam and elsewhere in the Marianas, however, the Spanish period left little trace. For well over a hundred years the Western map of the South Pacific remained hopelessly inaccurate and largely empty, with the notable exception of Abel Tasman’s discoveries in Australia and New Zealand in the mid-1600s.

All this was changed in little more than a decade—between 1767 and 1779—by the voyages of Captain Samuel Wallis, Admiral Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, and Captain James Cook. In the course of these voyages, Cook’s three in particular, great strides were made in filling in the map of the Pacific islands and describing the islands and their peoples to the West. The notion of a Pacific Paradise became firmly embedded in the Western imagination as eighteenth-century explorers found in the islands, especially Tahiti, evidence of mankind’s utopian existence in a state of nature.

Tahiti, the largest of the Society Islands, was fa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Maps

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: The Region and Its Peoples

- Part One Exploration, Contact, and Control

- Part Two Toward Independence and Elsewhere

- Part Three The Practice of Politics

- Part Four Coping with the Outside World

- Appendixes

- About the Book and Author

- Index