eBook - ePub

Chaos and Control

A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Unfolding Creative Minds

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores the role of chaos and control in the creative process as well as the difference between talent and creativity. Part One describes explores some of the common biases and pitfalls in the analysis and therapy of creative people, the role of the accidental in creative work, the nature of creative blocks, passion and its absence, as well as the problem of being able to exercise one's freedom. The author describes the special needs of creative patients, the common problems arising in therapy, its solutions, and, most importantly, the analyst's distinctive role when dealing with such patients. She also probes into the role of narcissism, neurosis, and psychosis on creative work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chaos and Control by Desy Safan-Gerard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THEORIES, CONDITIONS, AND OBSTACLES

CHAPTER ONE

Chaos and control in the creative process

Abook on creativity should pay special tribute to the life force that lies at the root of any creative act. Thus the reader may be surprised that this first chapter begins with the seminal role of destructiveness in creativity, a recurring theme in the various chapters of this book.

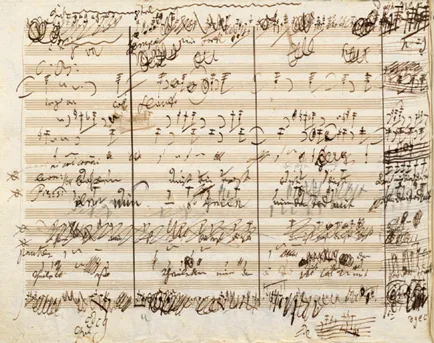

The tumult and chaos of one of Beethoven’s surviving sketches plunges us into an empathic turmoil. Trying to sort through the messy surface, erasures and frantically crossed out notes one cannot avoid feeling the composer’s anguish and frustration as he struggled in his search, not knowing yet what he was looking for. This is one of Beethoven’s surviving sketches from the finale of his only opera Fidelio (Figure 1.1), for which he wrote four overtures, before settling on the last one. These sketches, most beautiful on their own, constitute the basis for an understanding of his creative process and its ongoing destructiveness, an understanding that can be extended beyond Beethoven to represent the basis of the creative process in most fields.

At a certain stage during creative work destruction becomes as necessary as the ensuing reconstruction and control of its elements. From my photographic documentation of abstract paintings in progress, I have often been struck by the alternation of chaos and control.

Figure 1.1. Beethoven’s musical sketch for the sixth and three following measures before the trumpet signal in his Fidelio Opera, second act of the vocal quartet No. 15 Er sterbe, 1805. Photo credit: bpk Bildagentur/ Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Germany/Art Resource, NY.

The destruction of the painting structure represented by a chaotic image is typically followed by an organised image indicating that its elements are now under control. The destruction the artist engages in is a response to something not working out in the work when things seem to go awry. Such destruction restores the dialogue with the work in progress whereby the artist regains control. This sense of control arises once the artist is satisfied with the changes made and the dialogue with the work is restored.

Composer Lucky Choi says, “Destruction of my ‘child’ does not always come easy. There is often no alternative when I instinctively know when I have reached a dead end or I have gone down the wrong path. I somehow sense that I have lost communications with the work’s voice. What doesn’t work for this work may be saved and modified for another piece some day.” In a similar vein, gifted composer Jane Brockman writes, “I am struck by the efficiency of Nature’s cycles. This is true of composing also. Nothing is wasted. Vast quantities of musical detritus must be jettisoned to nourish the life of a new work.”

An exception can be made of Maurice Ravel’s La Valse, originally conceived as a ballet. Several times throughout the piece he engages in the destruction and reconstruction of its main theme. The audience’s pleasure is in their participation in Ravel’s cycles of creation and destruction with the waltz ending in a total collapse, but still under the composer’s control. As Jane Brockman suggests, “Perhaps we so enjoy it because we have all witnessed the creative cycle in nature where new life arises and is nurtured by the decomposition and destruction of old life”.

Destruction of work in progress may have different sources. Some-times the artist is unhappy about a painting in progress and, in anger or hate towards what is in it, ruthlessly destroys parts of it or the whole painting. Much anguish is stirred up when destroying a painting in what may have represented hours of loving involvement with it. After such destruction, a leap of faith moves the artist to engage in a renewed effort to create something of value again. At other times, out of an ongoing dialogue with work in progress, artists believe they are merely “responding” to the painting that seems to be asking them to do something different. There are many feelings involved in these chaotic situations, and I write about my own attempts to bring them under control in Chapter Thirteen, “Love and hate in the creative process,” Chapter Fourteen, “Destructiveness and reparation: A retrospective,” and Chapter Fifteen, “From mistake to mistake: The creative process in four large paintings”.

The role of destruction in creativity was introduced to psychoanalysis in 1912 by Viennese psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein, an early participant of the psychoanalytic movement, whose visionary contribution has long been forgotten. Her theoretical paper entitled “Destructive-ness as the cause of coming into being” not only discusses Jung, Freud, and the ideas of other early psychoanalysts, but also Nietzsche, Wagner, as well as Christian, Jewish and Asian mythology. She was invited to become part of Freud’s Vienna group of disciples after presenting this paper at one of their Wednesday meetings. According to Spielrein, we all have the desire to maintain our present condition, as well as the desire for transformation. The artist enjoys his “sublimated product” when he creates the “typical” instead of the “individual”. She concludes her paper claiming that “the purely personal can never be understood by others” (p. 164).

While experimenting with free drawings, British analyst and artist Marion Milner (discussed further in Chapter Ten) found that in the drawings that were satisfying to her “there had been this experiencing of a dialogue relationship between thought and the bit of the external world represented by the marks made on the paper” (1950, pp. 115–116). According to Milner, a dialogue between the artist and the work is essential to creativity. If the artist experiences the painting as a mere extension of herself, such dialogue with the work is not possible. We could then call the artistic process “narcissistic”, because the work is done “to” the painting, and not “with” the painting. If, instead, the painting becomes “the other”—having desires and demands of its own—there can be a transcendence of the preoccupation with the self. We can then engage in a true creative act, experiencing ourselves at the service of the work. It is at this point that the communication between the artist and the work begins—the artwork now has a life of its own and the creator can interact with it. This is also the case with writers who enter into a dialogue with their characters, but at times even experience their characters as taking over their creation.

The painting having a life of its own can involve not only the artist, but also the model. Writer James Lord (1965) posed eighteen times for a portrait made by his friend Alberto Giacometti and wrote a portrait of the artist at work:

An exceptional intimacy developed in the almost supernatural atmosphere of give and take that is inherent in the acts of posing and painting. The reciprocity at times seems almost unbearable. There is an identification between the model and the artist via the painting that gradually seems to become an independent, autonomous entity served by them both, each in his own way and oddly enough, equally. (Lord, 1965, p. 23)

James Lord recounts that, while sitting for Giacometti’s portrait, he would ask him to take a break for lunch. Giacometti would refuse—he didn’t want to stop at a time when the portrait was not going well. Two hours later, a quite hungry James Lord would ask again to take a break to have something to eat, but Giacometti would again refuse, claiming they shouldn’t stop now that the painting was going well!

Regarding writing, Joan Rivière, an early contributor to psychoanalysis, described how Freud exhorted her to write about a psychoanalytic idea that had occurred to her and he said:

“Write it, write it, put it down in black and white…. Get it out, produce it, make something of it—outside you, that is; give it an existence independently of you” (Rivière, 1958, p. 146). This is not unlike what happens in painting. There is a need to put on the painting all we have, to see it, to discover it, to find out what it is, to do something with it, to give it life. Much of what is put on the canvas at these times is voluntary, but some elements are experienced as accidental and reacted to as “messy” or “bad” (Ehrenzweig, 1967; Safân-Gerard, 1982). These are generally projections of split-off parts of the self that find their way into the work. Hopefully, in the course of creative work, these bad and messy accidents can become understood, appreciated, and integrated into the work (this is further elaborated in Chapter Three, “The role of the accident” and Chapter Fifteen, “From mistake to mistake”).

During the act of destruction of aspects of the work, the artist is concerned that there might not be anything worthwhile left after the attack. In his account, writer James Lord was dismayed at Giacometti’s continual destruction of the work in search of some elusive quality. He had to learn to trust Giacometti’s judgement that such destruction was necessary (Lord, 1965). Analyst Hanna Segal quoted the painter Elstir, in Marcel Proust, who said, “it is only by renouncing that one can recreate what one loves” (Segal, 1981, p. 190). Like Beethoven and Giacometti, the artist has the courage to destroy because he trusts that he can ultimately make it right, and that the work will survive. At these moments, all the artist has is the courage to destroy in hopes that the creation survives. The sense of otherness of what is created goes together with our realisation that it will survive our destructive attacks (Winnicott, 1971). The move from chaos to control that underlies the creation of art is not limited to the artistic form, be it music, painting, or other. It is also intrinsic to psychoanalysis. Chaos and control comprise the essence of creativity in both.

The artist needs to work through the elicited chaos in the work so that he can eventually achieve a measure of control. This is the aim of artistic creation. Likewise, the psychoanalyst has to respond to, sort out, and offer some understanding about the chaotic memories and feelings the patient may be experiencing. While the focus is on the patient, the creativity of the analyst is at stake because she has to respond to the content of the session and the feelings and expectations of the patient. While noticing her own feelings in response to the session in progress, she offers the patient an interpretation with care and concern. Such is the outcome of the creative work of the analyst. Art and psychoanalysis: two paths to creativity through destruction that engage the richness and wisdom of one’s inner life.

CHAPTER TWO

Talent and creativity

Quite often in my career as a psychoanalyst and visual artist, I had felt alone in the pursuit of understanding the creative process, its dysfunctions, and in finding ways to help creative patients in their quests for internal freedom. I had heard about Dr Jerome Oremland’s work on creativity and was honoured to be the discussant on his talk entitled “Talent and creativity” at the Los Angeles Institute of Psychoanalytic Studies (LAISPS) on March 29, 1981. Finally, I was in good company, enjoying his lecture in spite of his classical orientation. My psychoanalytic training had not yet begun, but I was already gravitating towards the progressive ideas of Melanie Klein and Wilfred Bion.

In my discussion, I was somewhat critical of the way Dr Oremland dealt with a couple of cases. To my surprise, in his response, he agreed with my criticism, stating that he had seen these patients over twenty years earlier and that he would not deal with them the same way now. He harboured no resentment about this and he later invited me to lecture on creativity in San Francisco, which led to a consolidation of our friendship. Having lost contact for several years, I had the pleasure of visiting Jerome in Sausalito, California in 2014. After a delightful lunch by the water, he invited me to his home to see again his impressive collection of Renaissance and Contemporary art. In our conversation, I mentioned the present book project, for which I was compiling my writings on creativity. He expressed great interest and was full of encouragement noting that, finally, the author of such a book would be an analyst and an artist.

Sadly, Dr Oremland died on February 19, 2016, so I was unable to gain his insight and commentary. With immense gratitude for his encouragement, support, and friendship, as well as his contribution to our of I dedicate this to his

Prototypical studies on creativity since Freud have been based on the content of the artwork, rather than the process of making it, which has given these studies a psychopathological flavour. This was later modified by Mary Gedo, viewing “art as autobiography” (1980), by John Gedo, recognising “creativity as an alternative to loving” (1983), and by Jerome Oremland describing “creativity as meta-autobiography” (2014). Their contributions to the understanding of the creative process are unparalleled.

I have recently reread John Gedo’s Portraits of the Artist: Psychoanalysis of Creativity and its Vicissitudes (1983). According to his own experience, the key to the psychology of men of genius is the underestimation that typifies their formative years. This leads to their “demonic efforts to create and to their fragile sense of worth” (p. 99). Concerning women artists, his impression was that “in our society, parents tend to be less tolerant of the eccentricities of their gifted daughters than of their gifted sons” (p. 99). I believe that this was true in my case. My mother revealed to me her embarrassment when I, at age three or four, would read out loud the advertisements posted in buses we were riding. She was afraid, she told me, that other passengers would think that her daughter was a freak. Later, in my adolescence, she was very critical of my hours of listening to contemporary music and told doctors that she was convinced that the dissonant music was the source of my chronic migraines.

Dr Gedo’s chapter five is particularly interesting; he describes in detail the work with a male homosexual patient who believed he had made a grave error in giving up his musical ambitions. Dr Gedo felt free from the constraints of being an analyst and suggested to the patient that it might not be too late. He writes, “Consequently, at an appropriate moment, I told him that he would forever be tortured by these doubts and regrets unless he obtained a reliable estimate, even at this late date, of the actual extent of his musical talent”. Challenged by this idea, the patient eventually resumed piano practice and submitted himself to a series of auditions before judges of progressively greater stature. Their verdicts were entirely consistent: the patient possessed “musicality” of the highest order, but his piano technique was too deficient to be remedied without years of concentrated effort. In other words, the patient was essentially correct in judging that he had missed his “true vocation” (p. 76). I was personally touched by this story, as I still regret not pursuing music as my primary occupation (more on this in Chapter Nine).

Dr Gedo ends his account of the treatment of this patient, “Although the analysis had proceeded reasonably well to his point, the patient had overcome neither his dissatisfaction with his wife nor his occasional homosexual activities—the latter becoming increasingly concentrated during periods when our work was for some reason temporarily interrupted. We were therefore completely unprepared for one of the consequences of his new routine of several hours of piano practice: never again did he feel the need for sexual relations with men!” (p. 76).

Biases of the analyst

Jerome Oremland reminds us that Greenacre (1957), Erikson (1959), Kris (1952) and others have concluded that creative people possess a special kind of mental functioning that is not necessarily neurotic and/or narcissistic. This shift in emphasis is not typically reflected in the work of clinicians. Today, artists are still perceived as “difficult”, narcissistic patients who elicit strong countertransference reactions in the analyst.

First, as Dr Oremland suggests, the creative patient is usually not involved with the analyst in the intense way other patients are involved. The analyst is only one person among many in a patient’s life, and certainly less important to the patient than his own artistic work. This is often difficult for the analyst to handle. The patient will tend to be perceived as distant and self-preoccupied, and the analyst might interpret accordingly.

Also, the analyst may envy the patient’s creativity as many analysts, at some point in their careers, experience a strong desire to produce something out of themselves, rather than always being in the helping role. My colleagues reveal that they often experience a sense of being drained, depleted of energy, with a strong need to “nourish” their own lives. If the analyst is doing creative work, he is less likely to resent the creativity of his patients. As is always the case, envy is often not perceived internally as such unless one is on the couch being analysed. This envy may be translated into a dislike for the patient, with accompanying justification. We know that analysis is most successful when the patient’s envy of the analyst is recognised and interpreted. This also applies to the analyst’s envy of the patient.

Another problem in therapy occurs when the analyst’s lack of understanding of the patient’s work results in countertransference reactions. If the analyst feels unable to aesthetically respond to the patient’s work—and the patient wants to share it—she might not know if her own lack of response is due to sheer ignorance or her envy of the patient’s creativity. It is indeed rare to find an analyst who is comfortable with her own ignorance in art matters. Recently, an analyst friend remarked to me, “This patient of mine has had very good reviews so the work must be good, but I don’t understand it at all. All I can do well is analyse. If the patient provides me with his associations, I can work with them.” On the other hand, another analyst friend, himself a respected psychoanalytic writer, would not allow a patient to bring into a session a piece of sculpture for which she had won an award. As per an analytic formula, he saw her request as “acting out”, limiting himself to question and interpret her need to bring in the work. This created a sustained crisis between the two, as the patient felt betrayed. The analyst’s denial of the patient’s need to bring the work in may have stemmed, at least in part, from his avoiding a situation in which his lack of understanding would become evident to him and the patient. His omnipotence would have been challenged and he might have felt narcissistically injured. The analyst’s fear of reacting to the patient’s work...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Preface to “Chaos and Control”

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Introduction

- Part I: Theories, Conditions, and Obstacles

- Part II: My Own Development

- References

- Index