![]()

1

Introduction to single-case experimental designs

Historical overview and basic concepts

Historical overview

Nomothetic and ideographic approaches

In 1894, Windelband (1894/1980) coined the terms nomothetic and ideographic to describe contrasting approaches in science for gathering evidence-based knowledge. According to him “The nomological sciences are concerned with what is invariably the case. The sciences of process [which he called ideographic] are concerned with what was once the case” (p. 175). In other words, the nomothetic (from the Greek word nomos, meaning law) approach focuses on establishing general laws (and generalisations) applicable to a class of phenomena; the ideographic approach focuses on describing and explaining single events or what Windelband describes as a “coherent sequence of acts or occurrences” (p. 174). Five years later, the terminology was introduced to psychology by Münsterberg (Hurlburt & Knapp, 2010); the nomothetic versus ideographic distinction in psychology was subsequently popularised by Allport (Robinson, 2011).

The nomothetic approach eventually became equated with the group-based methodology and statistical techniques being developed in the first quarter of the twentieth century to study individual differences (Robinson, 2011). For instance, in the context of neurorehabilitation, the nomothetic approach to investigating the effectiveness of an intervention (independent variable) on a cognitive/behavioural/motor impairment (dependent variable) consists of treating one group, while another group that is comparable in terms of relevant clinical characteristics is left untreated but is otherwise exposed to the same conditions as the treated group. Group differences on the variable of interest are then analysed using inferential statistics. Results can then (theoretically) be generalised to the population from which the study samples were drawn. This is, in essence, the between-groups methodology that has been firmly established in psychological research for the last century and with which most (if not all) rehabilitation clinicians are familiar.

The ideographic approach eventually became equated with the case-study method, although, strictly speaking, the ideographic approach does not refer to a particular method but to an objective, which is to explain an individual thing or phenomenon (Robinson, 2011). Traditionally, the case-study method has been used in a variety of disciplines throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Case studies in the medical (e.g. Broca, 1861; Wernicke, 1874) and psychoanalytic (e.g. Freud & Breuer, 1895/2004) literature were primarily qualitative and descriptive, and contained little, if any quantitative data, and there was certainly no attempt to exercise experimental control. Pioneers in experimental psychology such as Fechner, Wundt, Ebbinghaus, and Pavlov focused on the intensive study of individual organisms, but also collected and recorded quantitative data (Barlow & Nock, 2009; Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009). Developments in behavioural theory (particularly, operant conditioning techniques) during the first half of the twentieth century and the advent of behaviourism and subsequent focus on applied behaviour analysis, further popularised the use of single-case methodology in psychological research. Systematic collection of empirical data along with experimental control of variables was incorporated in single-case research, giving rise to what we now call single-case experimental designs (Barlow, Hersen, & Miss, 1973; Barlow & Nock, 2009).

The early years of single-case methods in neurorehabilitation

The 1960s saw studies using single-case methodology in neurorehabilitation gaining a presence in the literature. An early report is that of Goodkin (1966) who described four cases in a rehabilitation setting. Goodkin conducted a series of A-B designs (see Chapter 5) to evaluate the effect of the intervention (comprising feedback, contingent reinforcement and extinction) on a variety of presenting problems: speed of handwriting and operating a machine with the nondominant hand in a woman with left hemisphere stroke, speed and distance of propelling a wheelchair in a woman with Parkinson’s disease, increasing intelligible speech in a man whose left hemisphere stroke resulted in moderate to severe receptive and expressive aphasia, and decreasing irrelevant responses to questions and perseverative responses in a woman with (non-specified) speech disorder after left hemisphere stroke. Around the time of Goodkin’s article, single-case experiments already had a firm basis in the clinical psychology and education fields, focusing on the use of operant procedures, and frequently addressing challenging behaviours. Specialist journals, such as the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis first published in 1968 and Behavior Therapy in 1970, provided an avenue to publish the single-case experimental design (SCED), and, along with early textbooks (e.g. Hersen & Barlow, 1976; Kratochwill, 1978), saw SCEDs obtain standing as an established and accepted methodology.

By the 1970s, the field of neurorehabilitation saw SCEDs being increasingly applied in two domains in particular: challenging behaviours and neurogenic communication disorders. It was a logical step to adapt procedures used in clinical psychology for the treatment of challenging behaviours and apply them to neurological patients. Examples include use of A-B designs to reduce self-injurious behaviour in a 14-year-old girl with epilepsy (Adams, Klinge, & Keiser, 1973) and involuntary crying in an adult with multiple sclerosis (Brookshire, 1970).

From the outset, the field of speech and language pathology has embraced SCEDs and journals such as Aphasiology and the American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology among others regularly publish studies using SCED methodology. McReynolds and Kearns’s (1983) textbook, specifically aimed at using SCEDs in communication disorders, has exerted major influence in that field. The widespread use of the SCED has resulted in a rich evidence base, with SCED studies addressing different interventions for speech/language disorder. Early studies focused on aphasia after stroke, evaluating use of a range of interventions, such as stimulus repetition (Helmick & Wipplinger, 1975). The Helmick and Wipplinger study is probably one of the first studies in neurorehabilitation to use an alternating-treatments design (ATD) (see Chapter 7). The investigators examined the efficacy of two therapeutic procedures regarding dosage comparing amount of practice (6 vs 24 stimulus repetitions).

By contrast, during the 1970s there was only a smattering of SCED studies in other cognitive domains, such as memory, where Gianutsos and Gianutsos (1979) were among the first to use the multiple-baseline design (MBD) (see Chapter 6) in neurorehabilitation. They evaluated mnemonic training to improve verbal recall in four patients, three of whom had stroke. But it was not until the 1980s that studies using single-case methods were applied in a broader range of cognitive areas, such as attention (Sohlberg & Mateer, 1987; Wood, 1986), executive function (Cicerone & Wood, 1987; Jenning & Lubinski, 1981), memory (Glisky & Schacter, 1987; Wilson, 1981, 1982), neglect (Robertson, Gray, & McKenzie, 1988; Webster, Jones, Blanton, Gross, Beissel, & Wofford, 1984), and social communication skills (Brotherton, Thomas, Wisotzek, & Milan, 1988; Sohlberg, Sprunk, & Metzelaar, 1988). The 1980s also saw reports addressing everyday function in neurological patients, such as urinary continence (Cohen, 1986; O’Neil, 1982), washing and dressing (Giles & Morgan, 1988; Giles & Shore, 1989) and other functional activities involving arm and hand function (Kerley, 1982; Tate, 1987), wheelchair navigation (Gouvier, Cottam, Webster, Beissel, & Woffard, 1984), supported employment (Wehman et al., 1989) and consumer advocacy skills (Seekins, Fawcett, & Mathews, 1987). The O’Neill study is one of the earliest neurorehabilitation investigations to use a changing-criterion design (CCD) (see Chapter 8). The investigator treated urinary frequency in a 32-year-old woman with multiple sclerosis by increasing the duration between voiding in four incremental steps.

A number of reports from this early period used sophisticated designs with strong internal validity. Schloss, Thompson, Gajar, and Schloss (1985), for example, described a self-monitoring intervention to improve conversational skills of two males, aged in their twenties, with traumatic brain injury. The investigators used an MBD across behaviours within which was embedded an ATD to evaluate the effects of the self-monitoring training. The strong internal validity (described in more detail later in this chapter and in Chapter 2) was demonstrated by the investigators implementing the following procedures: (i) the study design contained experimental control in that the independent variable was experimentally manipulated, (ii) use of randomisation in the alternating-treatments component, (iii) measurement of the target behaviours continuously in each phase, (iv) use of observers to measure the target behaviours who were independent of the therapist delivering the intervention, (v) evaluation of inter-rater agreement of the observations which was found to be high (around 90%), and (vi) assessment of treatment adherence, which was also found to be high (100%).

From these beginnings, the SCED literature has grown. The NeuroRehab Evidence database (www.neurorehab-evidence.com),1 for example, contains more than 800 single-case experiments addressing the cognitive, communication, behavioural, emotional, and functional consequences of acquired brain impairment. The Appendix to this book summarises a set of 66 SCEDs in neurorehabilitation, mostly published during the past 15 years. The aim of the Appendix is to illustrate the variety of neurological conditions and functional domains treated, the types of target behaviours addressed and different ways in which they are measured, along with a range of interventions and design options.

Surveys of SCEDs in the literature

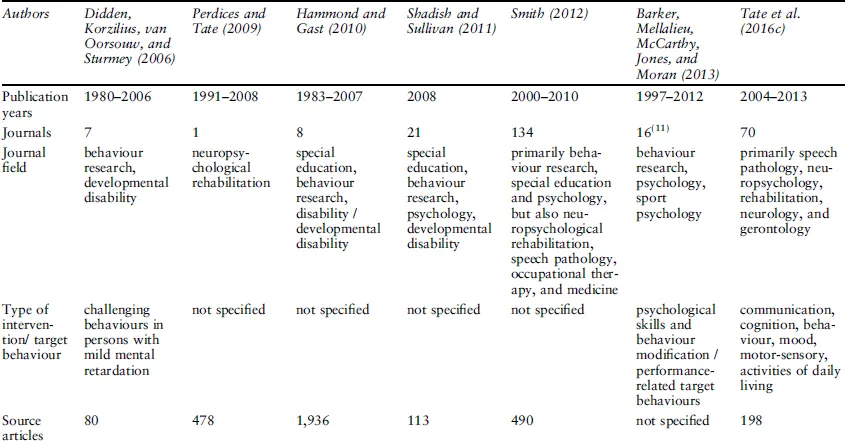

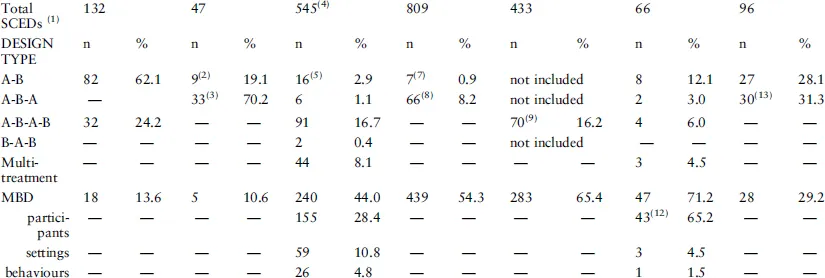

Table 1.1 summarises the findings of seven surveys that, inter alia, document the type of single-case designs published in various fields of research.2

TABLE 1.1 Summary of surveys of types of SCEDs in the published literature

Notes: — = no information provided; multi-treatment designs=withdrawal designs with more than one treatment, e.g., A-B-A-B-A-C-A-D; MBD=multiple-baseline design; ATD=alternating-treatments design; PTD=parallel treatments designs consisting of two simultaneous multiple-probe designs replicated across functionally equivalent behaviours; CCD=changing-criterion design; combination=combine two or more designs, e.g., A-B-A-B nested in the tiers of an MBD. (1) Some articles report data for more than one SCED; (2) includes variants, e.g., B-A; (3) includes variants of the standard design; (4) non-concurrent MBD/multiple probe designs, and simultaneous treatment designs (cf. ATD) not included in survey; (5) includes A-B-C designs; (6) includes adapted ATDs, which used two interventions focused on two similar but independent target behaviours; (7) includes A-B and designs that do not revert to a condition from the previous phase, e.g., A-B-C-D; (8) might have included A-B-A-B but this is not specified in the survey; (9) may include designs with additional phases, e.g., A-B-A-B-A-B, but this is not specified; (10) includes simultaneous treatment designs (cf. ATD); (11) 16 journals are identified in the article, but there is indication that more journals might have been surveyed; (12) includes two across-groups designs.; (13) includes variants (e.g. A-B-A-B; B-A-B)

The most salient feature of Table 1.1 is that, except for the Didden, Korzilius, van Oorsouw, and Sturmey (2006), Perdices and Tate (2009), and Tate, Sigmundsdottir, Doubleday, Rosenkoetter, Wakim, and Perdices (2016c) surveys, MBDs are the most common type of design, both in the behaviour/psychology and the sport psychology literature. According to Barlow et al. (2009) MBDs have become “the most well-known and widely used of the three alternatives to withdrawal or reversal designs” (p. 202). In a brief search of PubMed on 6 June 2007, they found 1,036 articles listed under the term “multiple baseline” while only 123 and 30 were listed under the term “alternating treatment” and “changing criterion” respectively. It is possible that there is some degree of sampling bias in the Perdices and Tate (2009) study, given that only one journal with a specific focus on neuropsychological rehabilitation was surveyed. Even so, in a more recent review of the neurorehabilitation literature sampling from a broader range of journals (n=70), Tate et al. (2016c) found that in general the MBD was not more common than other designs. The frequency of other design types is variable: of the 24 “mixed designs”3 identified by Smith (2012), 12 combined an MBD with a reversal design; of the 211 “combination designs” identified by Shadish and Sullivan (2011), 80 combined an MBD with an ATD. In addition to the four major designs discussed in this and the following chapters, there is a multitude of variations and combinations whose number would be “impossible to convey” (Kazdin, 2011, p. 227).

In a neurorehabilitation setting, the primary clinical focus is the treatment of one, or a small group of individuals. SCEDs interface seamlessly with this clinical focus (Hayes, 1981; Perdices & Tate, 2009; Tate, Taylor, & Aird, 2013b; Wilson, 1987). For neurorehabilitation practitioners, SCEDs provide not only a framework to systematically monitor and record clinical data, but also the means to analyse those data so that results can inform clinical practice, consistent with a practice-based evidence approach. Moreover, interventions can be delivered with scientific rigour and potentially more beneficial clinical outcomes achieved. In other words, they provide a scientifically sound tool that is accessible to the practitioner to help establish and fomen...