1

Diplomatic Practice

By J. Simon Rofe

One basic challenge in the study of diplomacy is what we call the ‘theory vs practice’ debate. The crux of this discussion is the perception there is a necessary disconnect between academics who often look at things from a broad, abstract perspective (i.e., ‘theory’) and the ambassador, or any other diplomat, who deals with practical issues on the ground (i.e., ‘practice’). However, posing the question of whether theory should ‘determine’ policy (because big ideas are easier to deal with than complex and contested detail), or if practice is ‘more important’ (because it’s real life), is a false dichotomy as diplomats spend most, if not all of their time crossing the line between theory and practice. In this text, a key point is that ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ are not distinct and need to be understood in relation to each other. In other words ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ do not exist in sealed boxes, but are terms that should be unpacked so we can see them as separate, but enmeshed aspects of a holistic discussion about the history and purpose of diplomacy.

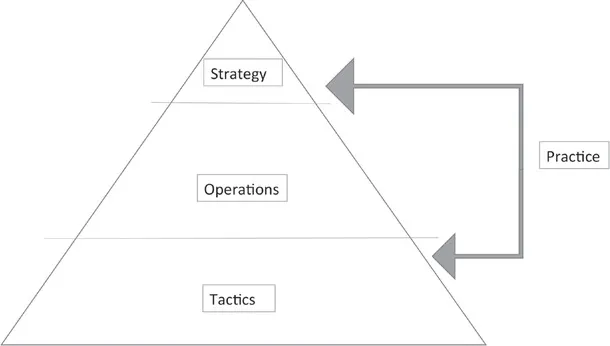

The meaning of ‘practice’ as applied here to diplomacy, relies on ideas of strategy, operations, and tactics. Traditionally, this is visualized as a hierarchy with strategy, sometimes called a ‘grand strategy,’ at the very top. Below that strategic level, lie operations, and below that, we come to tactics. Practice as used here is understood to be a level that effectively connects the ‘bottom’ of strategy and the ‘top’ of tactics. (See Figure 1.1.) This overlapping position is important because practice is both strategy-driven and tactical as the constitutive aspect of operations/implementation.

This chapter introduces the practices of diplomacy to show the ways that diplomacy manifests in the world around us, both in terms of institutional operations and tactics. However, to enhance understanding of these practices, some theoretical concepts, notably the concept of ‘power,’ are also introduced. These concepts and practices also serve as important reference points for the theories of diplomacy introduced in later chapters.

FIGURE 1.1 Hierarchy of Practice

‘Traditional’ Power and Diplomacy

In his memoirs, former US Secretary of State (1982–1988) George P. Schultz stated, “Power and Diplomacy work together” (Schultz, 2010, 10). While that may be the ideal case, even a casual look at the way power is understood or operationalized in the world suggests that many consider this pairing unevenly matched. For international politics, power is commonly thought of as being ‘over’ a territory and/or a people. Hans Morgenthau, a strong realist (the concept of ‘realism’ will be discussed in greater depth in Chapter 2), long argued for the centrality of power and plainly argued that, “International politics, like all politics, is a struggle for power. Whatever the ultimate aims of international politics, power is always the immediate aim” (Morgenthau, 1978, 29).

Clearly, power is understood in different ways and manifests itself through many different practices and, as we shall see, in different types of diplomacy. While Morgenthau and other realists may consider power to be measured primarily by military might, diplomatic practice relies on other dimensions such as financial strength, cultural resilience, or the power of suasion, which can all go a long way towards achieving one’s goals in international politics. Power matters insofar as power, be it perceived or real, can serve to facilitate or hinder the diplomatic process. In these circumstances, power may be about the ability to encourage or cajole parties to a particular outcome rather than to coerce an actor through its use—but whatever the source of power, it is rarely ‘neutral.’

Joseph S. Nye recognized at least some aspects of this dilemma as the Cold War was drawing to a close when he promoted the term ‘Soft Power’ in his 1990 book Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power, and it has become part of the lexicon of statesmen and scholars ever since. Unfortunately, the term’s broad use does not reflect its subtleties as it is generally used simply as the alternative/opposite to ‘Hard Power,’ the latter being the use of military capacity and what the military calls ‘kinetic power.’ Colloquially, hard power is the ability to blow things up, soft power the skill to achieve a goal without that application of force. The link to our discussion of diplomatic practices is logical if one accepts diplomatic scholar Herbert Butter-field’s notion that “diplomacy may include anything short of actual war” (Butterfield, 1966, 10) (Butterfield was a member of the English School who will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 3). Nye’s slightly less blunt argument is that “soft power rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others,” or the ability to attract others to a particular course of action. Further, that “soft power is not merely influence, though it is one source of influence. Influence can also rest on the hard power of threats or payments. And soft power is more than just persuasion or the ability to move people by argument, though that is an important part of it” (Nye, 2008, 95).

Potentially confusing the relationship between power and diplomacy even further, soft power is often used as a poor synonym for Public Diplomacy, which is a tactic discussed later in this chapter. Whatever the corollary, power is clearly a contested subject as there is no single agreement or understanding of its constitutive elements; yet it is fundamental to our understanding of the world as it pervades much of our decision-making. Is power, the power to do something—to make or destroy something or someone? Or is power the power to change people’s minds and change their lives? Power, in the abstract, has all of these facets to varying degrees; and while that is little consolation when facing an exam question, or the barrel of a loaded gun, power and diplomacy are distinct aspects of statecraft. The difficulty in terms of our understanding of power as a concept is related to the fact that international relations rarely locates power in a specific source, be it political, economic, military, or cultural. We will return to the point, but in the meantime, an outline of the basic processes and practices of diplomacy are needed to see how these power structures work and how they have evolved.

Fit for Purpose: Process of Diplomacy

A range of scholars have attempted to codify, classify, and catalogue diplomatic process, including Geoff Berridge in Diplomacy: Theory and Practice (Berridge, 2015). Nonetheless, in working towards an understanding of global diplomacy there are three activities core to each of the four types of diplomacy to be discussed in Part II: political, military, cultural, and economic. They are Communication, Representation, and Negotiation.

1. Communication is at the heart of diplomatic processes. Being able to communicate in technical terms through appropriate language and symbols, and emotionally with fellow human beings, is vital to ensure messages are conveyed in the way they are intended (Keller, 1956).

2. Representation in diplomacy is about a group or individual (‘a diplomat’) representing and communicating on behalf of a constituency, be that a locale or a state, when too many voices risk the message being poorly articulated. In the classic understanding, this means having the endorsement of a state, thus a diplomat can distinguish him or herself from others adopting the term ‘diplomat’ or ‘ambassador.’

3. Negotiation is the discussion, or conversation, that takes place between those representing a specific position with a view to reaching an agreement, even if the agreement is to keep negotiating.

The purpose of diplomacy, as demonstrated through these three key activities, does not operate in isolation or in any specific, given sequence, but from this triumvirate emerge specific roles and institutions, and are all interrelated as the activity of one influences the other across types of diplomacy. As tactics become common, they produce practice; as strategy changes, tactics continue to evolve. Diplomacy is derived from these three purposes and is evident throughout all four types of diplomacy we identify, to create both the structures and outcomes of this process.

Diplomats, Embassies, and Ministries of Foreign Affairs

The discussion of diplomatic practice begins with what may be considered the most immediately obvious actors and locations: Diplomats and Embassies and Ministries of Foreign Affairs. These institutions are most commonly associated with the activities of nation-states, but as will be seen, the practice of diplomacy happens at many levels.

Diplomats

Put simply, diplomats are those who implement diplomacy through communication, representation, and negotiation. From ancient times through to the modern era, diplomats have been an elite within society, often those close to the seat of executive power. This access has been critical to their success as diplomats in communicating, representing, and negotiating with their interlocutors. Stereotypically, they are aloof and reserved, ‘above politics,’ and male. However, while the reality is considerably more complicated than the stereotype, there is a more pointed story that seeks to associate the diplomat with the state. Some scholars, and some diplomats, would argue that a diplomat is someone working on behalf of the state; indeed, this is the clear implication of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (Bruns, 2014) that codified the roles and responsibilities of diplomatic relations as conducted by those accepted as ‘diplomats.’ The logic here is that those individuals representing actors other than states are just that—representatives without special standing or privilege.

It is also important to explore the corollary that diplomacy can be conducted by polities that are not states. Intergovernmental organizations such as the United Nations have both individuals as diplomats and to represent the apparatus of diplomacy, as they receive ambassadors and delegations from states, and have a functionally and geographically diverse bureaucracy for a variety of operations. The most important fact here is that the designation of ‘diplomat’ is essentially the accreditation they carry on behalf of their sovereign, whether that sovereign is a state, an intergovernmental organization, or single-issue campaigning group. This modern version differs in degree, but not entirely, from those conducting diplomacy in the distant past. For example, in the mid-seventeenth century, the representatives who gathered in Lower Saxony to negotiate what became known as the Treaty of Westphalia, covered in greater depth in the next chapter, were ‘accredited’ by a variety of ‘pre’-state actors including princedoms and city-states—often simultaneously. This type of arrangement was typical of those conducting diplomacy in antiquity.

Ambassadors

The most powerful diplomats are Ambassadors as Chief of Mission; that is, they are the single most important individual in a diplomatic Mission, most often an Embassy. Yet the term and the role have evolved considerably from their emergence in the Renaissance (approximately 15-17th centuries). The ranking of diplomats was based on a complex system that essentially relied on the title of the sovereign. The term ‘Ambassador’ was the preserve of the great powers of the day such as Spain, England, and France until the nineteenth century and the Congress of Vienna in 1815. After this gathering of those who had fought and won against Napoleon’s Republican France, the increase in number and sense of ‘equality’ of status among states meant the term became synonymous for those representatives of one state in another. Those performing the role previously had used the title Minister Plenipotentiary—meaning minister with ‘full powers’ to act on behalf of their sovereign as if they were that sovereign—thus creating a situation in which issues of protocol become highly contentious as the treatment of a Minister Plenipotentiary by a host country was literally considered to be their treatment of the sovereign as a person. However, these two titles are sometimes conflated such as in the case of the Chief of Mission of the United States to the United Kingdom, whose full title is “Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Court of St James’s”; the role being ‘extraordinary’ denotes the post as being the individual representative of the US President to the British monarch (Holmes & Rofe, 2012, 14).

The importance of rank in diplomacy is integral to its practice denoting the hierarchy in which diplomats operate. However, the ranking can be complex for at least two reasons. First, not all positions in the hierarchy are permanently filled by each state in relation to each bilateral arrangement. What this means in practice is that it is perfectly possible to have diplomatic relations without the exchange of ambassadors—those at the top of the hierarchy—or, as likely, there may be an exchange of ambassadors, but no military attaché. Second, appointments and longevity in many diplomatic posts, but most especially those at the top, often reflect the politics of the dispatching country. What these two factors mean is that the system is in a permanent state of flux, which allows for a number of exceptions or ‘quirks’ to the hierarchy.

Nonetheless, at the top is the Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary and the hierarchy flows down through the Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, and the Resident Minister or Counsellor Minister to the Chargé d’affaires as effectively the chief operating officer (see Figure 1.2). Other ad hoc positions may be created at the behest of a head of state, such as the Special Envoy. A specific example here would be the appointment by the United States of a Special Envoy for Northern Ireland, former Senator George Mitchell, in 1995, at the equivalent rank of Ambassador. With such ad hoc appointments, the question arises as to the longevity of the post. Formality has always been a part of the diplomat’s life and is seen throughout the ambassadorial appointment. The process of accreditation is the presentation of a letter from the dispatching head of state that the appointee presents physically to the receiving head of stat...