eBook - ePub

The Environmental Tradition

Studies in the architecture of environment

- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text brings together a unique collection of writing by a leading researcher and critic which outlines the evolution of the environmental dimension of architectural theory and practice in the past twenty-five years. It deals with the transformation of the environmental design field which was brought about by the growth of energy awareness in the 1970s and 1980s, and places environmental issues in the broader theoretical and historical context in architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Environmental Tradition by Dr Dean Hawkes,Dean Hawkes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture General| 1 | The theoretical basis of comfort in ‘selective’ environments |

1.1

Environmental control, minimal system.

Environmental control, minimal system.

Until quite recently the theory and practice of environmental control in buildings did not take into account the nature of the voluntary responses of building occupants to the environmental conditions they experience. To some degree this neglect was a reflection of the complexity of the subject, but was also a consequence of the predominant view of the aims and methods of environmental control. In this, the desired environment is specified as a series of precise statements about temperature, ventilation rate, illumination levels and so forth. These are maintained within quite narrow limits and this usually means, in practice, that reliance is placed upon mechanical systems which are, in turn, subjected to automatic control.

The historical influences upon the theory and practice of environmental control have been set out at some length.1 These can be seen to have followed a series of logical steps along a line of development established by the paradigms of building science and of the modern movement in architecture, with their respective concerns with scientific precision and of a definite, if not definitive, relationship between form and function.

The validity of these assumptions has been questioned in recent years, a notable ‘early warning’ being that issued by Musgrove in 1966.2 As part of this critique, a conceptual model of the environmental system in architecture was developed.3 This led directly to an investigation of the response of the occupants of five primary school buildings to the different, and differing, environments they experienced. Analysis of the results of this work led to the definition of a distinction between the exclusive and selective modes of environment.

Further work set out a series of rudimentary propositions about the nature of a selective building and the kind of environment it might offer.4 These were subsequently developed and found concrete expression in a design for a primary school to be constructed at Locksheath in Hampshire.5

1.2

The primitive hut, after Laugier.

The primitive hut, after Laugier.

The environmental system

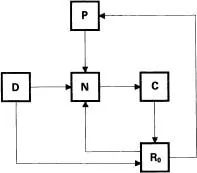

If we take an evolutionary view of humanity’s attempts to control the environment we can begin by describing the situation of humans in nature (Figure 1.1). Using terminology from the theory of cybernetics, in this Figure, D is a set of environmental disturbances which impinge upon a person, C is the set of physiological variables which determine the person’s state of comfort, N is the channel through which D is transmitted to C and is, in effect, a combination of the physical environment and the individual’s physiology. The precise state of N will depend upon certain parameters such as geographical location and body posture and these are represented by P. Even in this minimal system there are some opportunities for control and this is indicated by the regulating term RO.

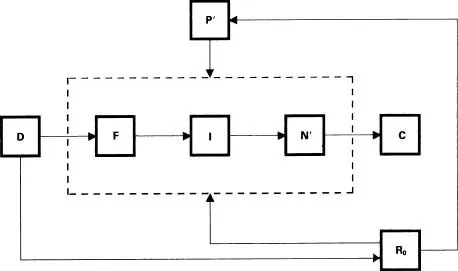

Primitive humanity’s adoption of clothing and shelter, the primitive hut beloved of architectural theoreticians (Figure 1.2), may be represented by the next development of the diagram (Figure 1.3). The new terms are F, which in cybernetics terminology is a filter and, in this particular case, can be taken to be the fabric of the building; I is a description of the internal environment; N becomes N’ to represent the effects of clothing and P’ allows for the wider range of parameters now available as a result of the variability of both clothing and the building fabric.

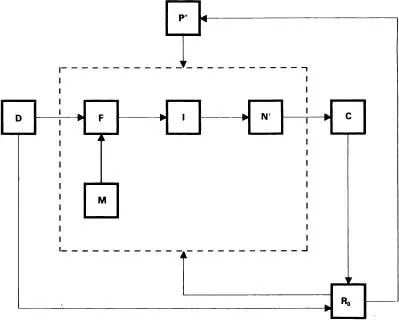

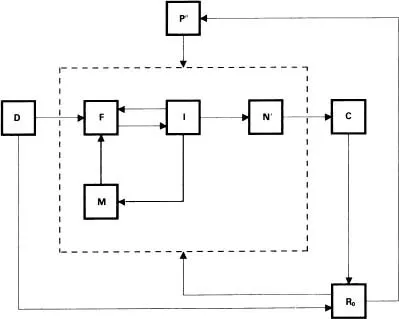

In our evolutionary account the benefits of shelter are soon augmented by the introduction of ‘plant’, M (Figure 1.4). This adds further parameters to the system, P", and is subjected to regulation by the occupant, even if, in the primitive case, this would amount to no more than adding wood to the fire! A complete picture of the system that is possible in a modern building is achieved by adding automatic controls on plant and fabric (Figure 1.5).

In diagrammatic form we now have a broad representation of the full range of possibilities of environmental control in buildings. Clearly, the reality in any practical building is much more complex. The possible combinations of form, construction and plant are numerous and the environment itself has many dimensions of heat, light and sound. The value of the model is that it provides us with a framework within which we may describe and classify approaches to control. If we translate the abstract terminology of this model into the language of building we can illustrate the essential difference between the exclusive and selective modes of control.

In seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the subject four questions were posed:

1.3

Environmental control augmented by clothing and building fabric.

Environmental control augmented by clothing and building fabric.

• What is the potential for variation of environmental conditions which is offered by buildings of different types?

• To what extent do the occupants of buildings take active steps to modify the environment, and at what point?

• How wide is the range of conditions which is tolerated?

• Does this ‘toleration’ demand changes in activity patterns?

The study was based upon specific ‘teaching spaces’. All, except one, were distinct classrooms, in five primary schools in Essex, which were made available with generous assistance from the Education and Architect’s Departments of Essex County Council. Each was equipped with an extensive monitoring installation to record the major variables of the physical environment – temperatures, lighting levels, etc. – throughout a full annual cycle. These were supplemented by further manual measurements and, most important, by observations of the activities and responses of the occupants.

Clearly, a sample of this size does not produce data which satisfy standard statistical criteria. The project was a pilot study, which aimed to embrace a wide range of environmental variables, rather than isolate a single relationship for study. The results have been described in full elsewhere6 and only the main conclusions are presented here. Under the heading ‘User priorities’ it was found that,

Great emphasis was placed by teaching staff on the ability to control the conditions in their own space. The one school in our sample which was mechanically controlled caused the greatest user dissatisfaction … User control would seem to be an important source of psychological satisfaction.

1.4

Environmental control augmented by plant.

Environmental control augmented by plant.

User controls available were manipulated in response to external conditions, such as direct sunshine, impinging on the space, and to vary internal conditions to fit teaching requirements … A range of conditions was found to be acceptable rather than any exact performance standard. Comfort depended on a complex interaction of air and radiant temperatures, air flow speeds, direct sunshine. The appreciation of these conditions also varied with activity patterns.

Our work shows that, rather than precise fixed standards, a variable environment is preferred. Design standards cannot be set as goals in the design process, but must be set as a range of acceptable levels and interactions.

The study also examined the effect of the design of building elements, ‘Performance of the parts’. In this,

… the importance of the detailed design of each element became apparent. The design of windows, for example, is a crucially important factor in determining the internal environment … In design work it is important to be able to describe this detailed performance … for it is at this level that user controls are designed.

From this point the next step was to consider the ‘Design of control mechanisms’:

Controls which are to be used by a variety of individuals must be comprehensible … Immediate response is required by the occupants from their action. A response is triggered by unacceptable or inappropriate conditions, which require instant relief … The spur to action to rectify discomfort is perhaps more reliable than the memory to return and undo the response when comfort is restored. Thus, especially for energy-consuming mechanisms, a shut-off sensor might have to be combined with the user switch.

1.5

Occupant control augmented by automatic controls.

Occupant control augmented by automatic controls.

The adoption of automatic controls on environmental plant in buildings is often justified by the argument that this ensures efficient use of energy by preventing ‘interference’ by the occupants. In a building in which mechanical systems are the predominant means of environmental control, exclusive buildings in our definition above, this is almost certainly the case. In a selective building, however, such generalizations can be misleading. This question of the effect of user actions upon ‘Energy inputs’ was considered in these studies:

We would suggest that by extending user control to achieve a closer meshing of their demands with the environment, considerable energy efficiency can be achieved. Firstly, this process involves detailed examination of the ways in which the external environment impinges on the building and the possible responses of the building to that. Rather than rejecting these influences and seeking to exclude them, certain benefits, such as passive solar heat gains, wind cooling or natural lighting, can be exploited as well as controlled.

Secondly, it is proposed that through the user being able to satisfy his own demands, a closer fit is found between activities and environments. Inputs of energy became more closely allied to needs rather than to maintaining imposed standards. Optimising controls must be developed which balance user demands and forgetfulness with energy criteria; energy should not be spent when not needed when, for example, the windows are open or the room is empty.

A major problem in communicating the results of architectural research to designers lies in the fact that research projects must, almost inevitably, conclude with abstract statements of general principle. Both the theoretical model of the environmental system described here, and the conclusions of the field studies project fall some way short of providing explicit guidance for actual design. In this instance, however, the research workers were given the opportunity to participate in the development of a series of more explicit statements on the architectural implications of their work. In association with the Architect’s Department of Hampshire County Council an exploratory study was undertaken.7 In this the many strands of this research began to come together.

Some studies of the potential of passive solar heating, which is implicit in the general possibilities of selective designs in school buildings, showed that the more dispersed plan forms and elaborate cross-sections implied by the selective approach could, if properly developed, offer substantial energy savings over conventional designs and, c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One Theory

- 1 The theoretical basis of comfort in ‘selective' environments

- 2 Building shape and energy use

- 3 Types, norms and habit in environmental design

- 4 Precedent and theory in the design of auditoria

- 5 Objective knowledge and the art and science of architecture

- 6 Space for services: the architectural dimension

- 7 The language barrier

- 8 Environment at the threshold

- 9 The Cambridge School and the environmental tradition

- Part Two Design

- 10 Wallasey School: pioneer of solar design Architect: Emslie A. Morgan

- 11 Netley Abbey Infants' School Architect: Hampshire County Council

- 12 CEGB Building, Bristol Architect: Arup Associates

- 13 Gateway Two, the Wiggins Teape Building, Basingstoke Architect: Arup Associates

- 14 St Mary's Hospital, Isle of Wight Architect: Ahrends, Burton & Koralek

- 15 Cassa Rurale e Artigianale, Brendola Architect: Sergio Los

- 16 Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre Architect: Erik Sørenson

- 17 The Sainsbury Wing, National Gallery, London Architect: Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown

- 18 Artistic achievements: the art museums of Louis I. Kahn

- Illustration and text acknowledgements

- Index