eBook - ePub

Tecpan Guatemala

A Modern Maya Town In Global And Local Context

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book discusses the indigenous people of Tecpan Guatemala, a predominantly Kaqchikel Maya town in the Guatemalan highlands. It seeks to build on the traditional strengths of ethnography while rejecting overly romantic and isolationist tendencies in the genre.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tecpan Guatemala by Edward F Fischer,Carol Hendrickson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Tecpán

A LAND OF CONTRASTS

A place of striking contrasts and deep contradictions, Guatemala eludes easy description. Visitors to this small Central American country (about the size of Tennessee but with an estimated population of just over 12.5 million) are first stuck by the dramatic landscape of the highlands: rich green valleys nestled between imposing mountains, crystalline lakes surrounded by rumbling volcanoes—the evocative clichés of Guatemalan tourist brochures. It does not take long, however, to note the human contrasts as well, as the country is home to both some of the wealthiest and some of the poorest people in Latin America. Shanty towns clinging to ravine slopes ring Guatemala City’s affluent neighborhoods, where houses are protected by barbed-wire and glass-shard-topped walls and patrolled by armed guards. Likewise, the peace of the agricultural landscape verdant with crops is punctured by impoverished villages, rutted dirt roads, and bony barking dogs.

Traveling west toward Tecpán from Guatemala City on the Pan-American Highway (the two-lane asphalt road that serves as Guatemala’s primary transportation artery), one climbs almost 2,000 feet in little more than 50 kilometers. Ears popping from the rapid change in altitude, travelers are then met by a series of fertile and intensively cultivated valleys, ending in the green expanse of the Tecpán Valley, which is crisscrossed with streams and planted abundantly with corn, beans, and squash as well broccoli, cabbage, and snow peas. On the south side of the Pan-American Highway lies the active volcano chain that divides the highlands from the more temperate Pacific Coastal plain, while on the north rises the older mountain chain of the Continental Divide. In the early 1980s the forested slopes to the west and north of Tecpán’s town center were troubled places, home to guerrilla groups, army camps, and refugee settlements as the civil war simmered and exploded. Beyond the forests far to the north, the mountain ranges drop off dramatically, leading into the vast expanse of lowlands covered by dense tropical forest. The hills and mountains closest to town have been largely deforested, accentuating the steep inclines. These are covered in small maize and bean plots or left bare, symbols of such social issues as unequal access to quality agricultural land, the ecological issues of deforestation, and political favoritism in the use of community resources.

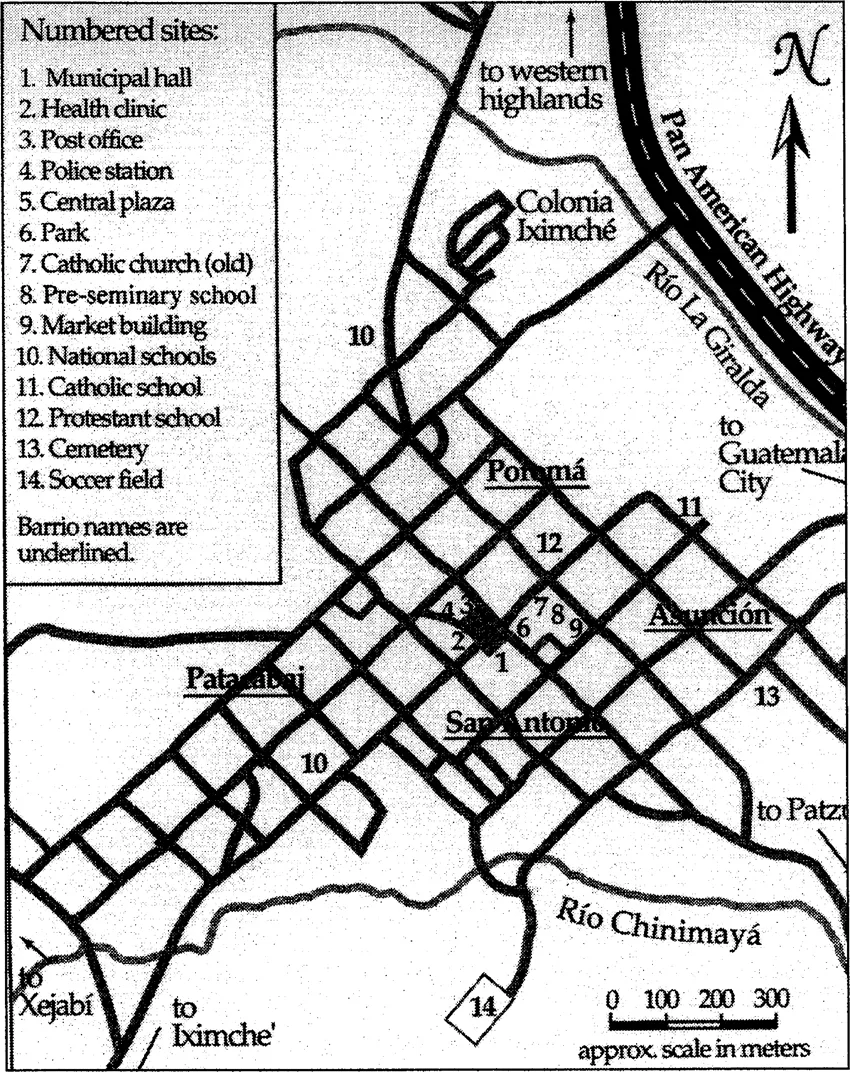

One of the two principal entrances to Tecpán lies at kilometer marker 78 on the Pan-American Highway and is marked by a slightly-more-than-human-sized concrete pyramid with text noting that Tecpán was Guatemala’s first Spanish capital and the site of the precontact Kaqchikel Maya capital (Iximche’). Jumbled around it and dwarfing this modest monument are billboards with an athletic blond male model hawking Rubios cigarettes; an idealized rendition of a Maya woman handing you a bottle of Quetzalteca Especial grain alcohol; and signature logos of various sodas, electronic products, and local establishments. At almost all hours of the day there are small groups of people standing around on both sides of the highway, waiting for buses to pick them up.

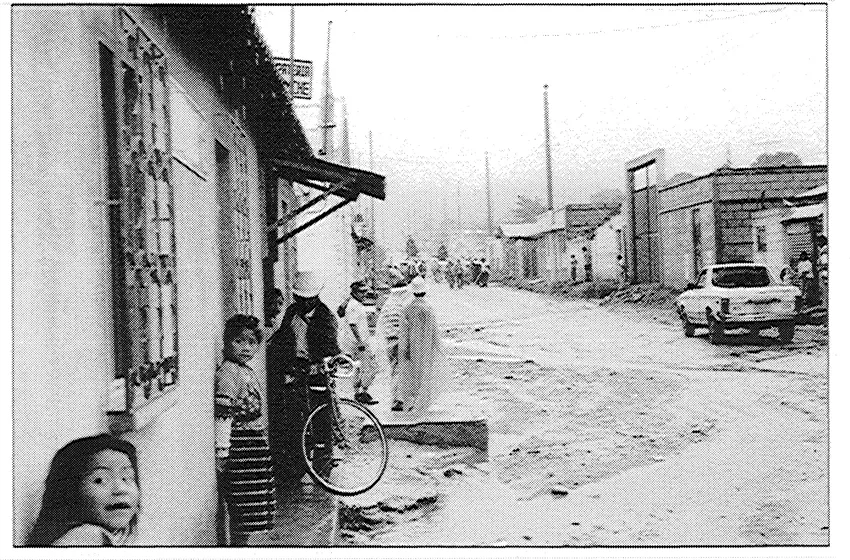

Entering Tecpán, a visitor would have reason to label this a fairly traditional Maya town. The majority (about 70 percent) of its approximately 10,000 residents1 are indigenous people who speak Kaqchikel Mayan, the native language; most of the women wear the brightly colored, hand-woven dress, and many weave on the backstrap loom. Maya religious life is evident in the centuries-old Catholic church and at shrines and altars around the town, and the large weekly market is a picture book image of the sort of thing tourists flock to the country to see and experience. Tecpán is also a town in flux and firmly ensconced in (if on the periphery of) the global scheme of things. Since the earliest days of Spanish contact, the Kaqchikel Maya of Tecpán have selectively embraced aspects of Spanish—and more broadly Western—life while retaining a clear sense of their own identity. Today, Tecpán is known throughout the region as an affluent and progressive Indian town: trucks and cars increasingly crowd the streets; a bootleg cable system supplies homes with HBO and other foreign fare; an Internet café connects its young customers to the larger world; shopping centers have opened and more are being built; evangelical Protestant churches and those of other Christian religions number in the dozens in town and claim thousands of the faithful; and Tecpán Maya have professional jobs as teachers, bankers, health care providers, and social workers as well as heads of publishing, transportation, and computer operations.

In contrast to the dramatic landscape, the urban setting of Tecpán appears drab, a relic of the hasty reconstruction following the 1976 earthquake. Guidebooks, when they deign to mention it at all, describe Tecpán as an unremarkable place, notable only for its proximity to an archaeological park at Iximche’ and the scattering of roadside restaurants along the Pan-American Highway. And so it may seem to the casual visitor, the dusty streets and cinder block buildings not unlike so many other highland Maya towns. There is no souvenir market, nor is it particularly gringo-friendly (some might find the occasional catcalls and shouts of “gringo” off-putting). Beneath this somewhat gritty veneer, however, lies a place of great interest, both in terms of regional history and modern community organization. Summary guidebook accounts miss the more subtle qualities of life in a place like Tecpán, qualities that reveal themselves only after longer residence.

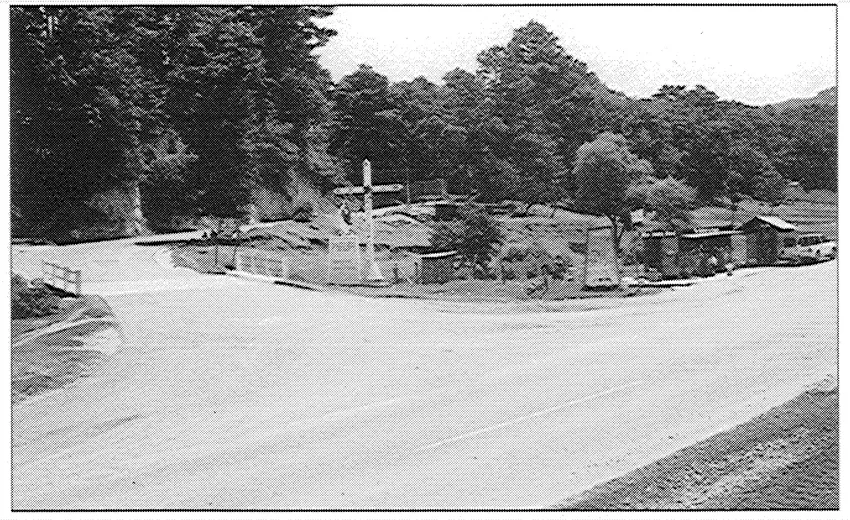

Figure 1.1 The turnoff to Tecpán from the Pan-American Highway.

Over 7,000 feet above sea level, the area is known as tierra fría because of the year-round chilly climate. The high altitude has its advantages and disadvantages. Tropical diseases that plague the lowland areas are almost nonexistent. There are few mosquitoes, and certain crops, including a hybrid form of maize, can have multiple harvests every year. But, befitting its geographic designation as tierra fría, Tecpán does get cold,… a bone-chilling cold especially pronounced during the rainy season, when nothing ever seems to get completely dry. Frosts are common at night around the New Year, and upon waking in the morning one frequently encounters a thin layer of ice around the edges of the pilas, the large outdoor sinks that serve as water storage basins. There is nothing quite so invigorating as bathing in the brisk morning air in the icy water of a pila. Although the area occasionally reaches freezing temperatures, snow is unheard of, and even on the coldest days the sun shines with an intensity found only at such high altitudes and low latitudes, allowing one to be simultaneously chilled and warmed.

Tecpanecos joke that their town has but two seasons, one muddy and the other dusty. Indeed, the temperature varies only slightly across the seasons, from lows near freezing some nights in late December and early January to daytime highs in the 80s (F) on the occasional sunny July and August day. During invierno (“winter” or the rainy season)—when the town’s streets turn into impassable rivers—the rain is fairly predictable, coming in heavy showers in the afternoons and/or evenings. In fact, some three-quarters of total yearly rainfall occurs between early May and late October. But this predictability does not make it any less inconvenient: Outside work must be stopped, people are soaked, and clothes often take days to dry. By September everyone is ready to see the end of the rain and mud, if for no other reason than to shake off the lingering chill that accompanies the frigid wetness. But by mid-November almost everything in town is covered by a fine layer of dust, churned up by children playing on packed earth patios and by passing cars and foot traffic on the town’s now dusty streets. To protect against the polvo (dust) invasion, people are particularly assiduous in covering objects of value in their homes: prime objects for servilletas (covering clothes) are TVs, VCRs, radios, blenders, treadle sewing machines, comfy chairs and sofas, computers, and/or cars.

Figure 1.2 The road to Iximche’ in 1994 (before it was paved) during the rainy season. Note the procession for San Francisco, the town’s patron saint.

Tecpán is a bi-ethnic town, inhabited by Maya and ladinos. Aside from these two groups, there are only occasional transient gringo residents: anthropologists or other foreign students, Peace Corp or other volunteers, and missionaries. There is also one black man living in town, a migrant from the Caribbean coast who plays in a local marimba band. Depending on the context and the person involved, native Tecpanecos refer to themselves, and are referred to by others, as indígenas, Maya, naturales, Kaqchikeles, or (generally pejoratively) indios,2 and they make up a majority of Tecpán residents (about 70 percent in the town center, and close to 95 percent in the surrounding countryside). The rest of the population is commonly referred to as ladinos, non-Indians of putative Spanish descent. In Kaqchikel, the term kaxlan refers to ladinos (and more broadly to any non-Maya peoples), and kaxlan acts as a modifier in a number of phrases to denote Western-style products: kaxlan ixim (kaxlan corn or “wheat”), kaxlan way (kaxlan tortilla or “wheat bread”), and kaxlan po’t (a Western-style blouse, po’t referring to the handwoven blouses that Maya women wear). Ethnic tensions between Maya and ladinos historically run high in Tecpán (as is true in communities throughout the highlands), a vestige of colonial power relations. At the same time, Tecpanecos often note with pride the genuine harmony and good relations between Indians and ladinos that prevail in town today.

Figure 1.3 Street map of Tecpán.

OPENING CLOSED COMMUNITIES

Earlier ethnographies of the Maya tended to stress the individuality of communities and their isolated and insulated nature. Eric Wolf (1957) applied the term “closed corporate peasant community” to refer to such social formations that were inward rather than outward looking, resistant to external change, and yet fundamentally unstable. Wolf writes that these communities show “not only a marked tendency to exclude the outsider as a person, but also to limit the flow of outside goods and ideas into the community … [they are] socially and culturally isolated from the larger society in which they exist … [a position] reinforced by the parochial, localocentric attitudes of the community” (1957: 4–5). At the same time, Wolf situated his model into a formulation of the colonial world system: the closed corporate peasant community was a response to the tributary mode of production imposed by Spaniards and their descendants. Thus he distinguished between “internal functions” (sociocultural isolation) and “external functions” (funneling economic resources), seeing isolation as an internal function that is allowed and reinforced through the mechanisms of tributary extraction, an external function (1957: 11–13).

Wolf published an article in 1986 in which he notes that his early work was “overly schematic and not a little naive” (326). Yet even today there is a tendency to stress the isolation of Maya communities in analyses of Guatemalan society: They speak different languages and dialects, they have lives facing inward to town markets and churches, and Maya from different towns exhibit a seeming unwillingness to join together to fight common problems. Carol Smith (1991) argues that isolation and atomization of rural Maya communities has proven to be an effective strategy for fighting impositions from the Guatemalan state: There are no “one size fits all” policies, and thus many centralized state initiatives are doomed to fail because of the complex of circumstances in the different communities in which they are enacted. Moreover, from precontact times to today, geographic barriers have hindered widespread communication among communities, and community allegiances are certainly strong. Even staunch advocates of pan-Maya activism sometimes exhibit strong town loyalties when interacting with people from other communities.

It is often remarked that the world is a much smaller place today than ever before, and certainly physical mobility and virtual communications have made the world easier to navigate at the turn of the millennium. Anthropologists such as Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson (1992) have argued that this makes models of culture based on particular real world locations dated. But in seemingly marginal global sites such as Tecpán (although here we need to ask, marginal for what people and what purposes?), physical location is still a primary social determinant. Those with whom a person interacts on a daily basis, who have likely known that person since birth, create a social environment in which all must live. These are the hard-to-escape ties of kinship and community.

Yet it is possible to overstate Tecpán’s isolation. Tecpanecos and Maya in general have long maintained wide-ranging connections, through both trade and political alliances, dating back to far before the arrival of the Spaniards. During the precontact period, Iximche’ had ties with groups as far north as the Aztecs in Central Mexico and likely as far south as Panama. Native documents even record that Montezuma had sent messengers to the Kaqchikel court in 1510 to warn the Kaqchikeles of sightings of strange white peoples in large ships. During the colonial period, the town was linked to regional and national markets, and today Tecpanecos are exceptionally mobile and well traveled by Guatemalan standards. A number of townspeople (mostly young men) have traveled to the United States to study or to work and earn money (part of which is sent home via Western Union, which has a branch in a local bank). More and more households are getting telephones in the aftermath of the national phone company being privatized, and Tecpanecos have proven to be savvy shoppers in the newly competitive market for long distance and international calls. Off the town square there are a number of small video parlors, usually nothing more than a simple store front containing benches, a television, a VCR, and a rental desk. The preferred fare is dubbed kung-fu movies and Rambo-like action films from Hollywood, peppered with an assortment of children’s offerings, science fiction, and soft porn from Mexico.

Perhaps the most troubling evidence of global-local ties comes from the violence of the 1980s, a period in which Tecpán, like many other highland Maya communities, found itself in the midst of a complex civil war, fueled by the competing Western ideologies of the Cold War. The violence reached Tecpán in force in 1981. In May of that year, the town priest, a moderately progressive man by most accounts, was shot down outside the parish house on a busy market day. “Unknown men” (the desconocidos to whom most such attacks are attributed) drove up on a motorcycle, shot the priest, and roared off. Presumably in retaliation (for the unknown men were almost certainly part of the state’s military apparatus), guerrilla troops entered Tecpán’s town center in November. The occupation lasted only a few hours, but the individuals involved were able to damage several buildings—the town hall was dynamited and the health center, post office, police headquarters, and jail were riddled with gunfire—and speak with townspeople. It did not take long for the army to arrive in town en masse, and they set up a garrison on the central square that was to remain for eight years. Many people were taken from their homes and to the garrison for questioning, never to return. People were frightened, and fear was palpable in the town. There are no good estimates of how many people were killed or tortured in Tecpán; certainly fewer than in some other towns, although not an insignificant number. There are numerous clandestine graves in the countryside surrounding town. Many people had close relatives killed; all know of someone who suffered the fate. The situation became so dire in 1981 and 1...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editor Preface

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Tecpán

- 2 The Guatemalan Context

- 3 Maya Histories

- 4 Natural Disaster, Political Violence, and Cultural Resurgence

- 5 Kaqchikel Hearts, Souls, and Selves: Competing Religions and Worldviews

- 6 Language, Dress, and Identity

- 7 The Land and Its Fruits: Cultural Associations in Changing Economic Times

- Conclusion: Tecpán Maya in the Contemporary World

- Glossary

- References

- Index