eBook - ePub

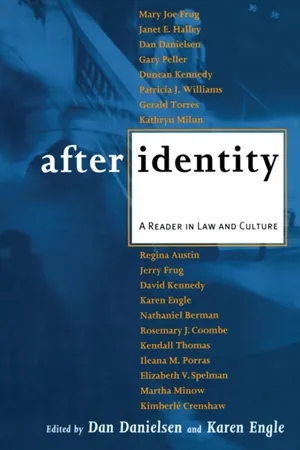

After Identity

A Reader in Law and Culture

- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Authored by the leading voices in critical legal studies, feminist legal theory, critical race theory and queer legal theory, After Identity explores the importance of sexual, national and other identities in people's lived experiences while simultaneously challenging the limits of legal strategies focused on traditional identity groups. These new ways of thinking about cultural identity have implications for strategies for legal reform, as well as for progressive thinking generally about theory, culture and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access After Identity by Dan Danielsen, Karen Engle, Dan Danielsen,Karen Engle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Sexuality

Introduction to Sexuality

WE BEGIN OUR PRESENTATION of post-identity scholarship with essays on sexuality. Sexuality seems a good place to start, in part because of the curious and often contradictory images of sexual identity that pervade contemporary culture. On one hand, sexuality seems biologically determined and beyond our control, while on the other it is championed as a realm of private freedom and choice where our most secret desires might find expression. At once public identity and private practice, compulsive and consensual, natural and nurtured, sexuality, like gender, both tracks and violates legal categories. The articles in this Part explore these conflicting faces of sexuality and gender while seeking a progressive agenda for law.

Liberal legal rules often negotiate these different images of sexuality through the assertion of an unduly formal distinction between status and conduct. In some ways, such a distinction seems to make sense. Although we are generally unable to choose (at least initially) whether to be biologically male or female, it seems most of us can decide whether to engage in prostitution or to have a child. Or while we might feel that we have little choice about whether to be homosexual or heterosexual, we can probably opt to participate in or abstain from certain types of sexual activity. In other words, our status often seems fixed, while our conduct usually seems controllable. Not surprisingly, then, liberal legal rules generally tolerate a greater diversity in the status category than in the conduct area. The Clinton Administration's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" military policy provides a good example of such rules, as does the criminalization of homosexual sodomy and prostitution.

The essays in this Part explore and explode this distinction between conduct and status. They do so by challenging both the asserted stability of status and the consensual nature of conduct, while maintaining that status and conduct can only be understood in relation to each other. For example, legal rules both construct and represent images of gender and sexuality by encouraging or proscribing certain types of behavior.

Mary Joe Frug investigates this relationship between status and conduct by looking at the criminalization of prostitution. She argues that rules about prostitution effectively divide all women into good girls and prostitutes. Potential ambiguity about one's good girl or bad girl status disciplines all women by encouraging certain forms of acceptable behavior. This criminalization of an apparently marginal activity has further meaning for all women as part of a complex of legal rules and cultural meanings. For example, when considered with such rules as restrictions on abortion that encourage reproduction and motherhood (thereby maternalizing the female body), and rules about rape and sexual harassment that fail to provide adequate protection against physical abuse to women (thereby terrorizing the female body), the prohibition against prostitution sends a message to all women that if their safety lies anywhere, it is in a monogamous heterosexual reproductive relationship. The more women deviate from this framework of acceptable gendered behavior, the more they risk being disciplined, either directly by the rules criminalizing prostitution, or indirectly, through the law's failure to protect them from abuse.

Similarly, Janet Halley argues that legal rules reinforce "the closet" by directly disciplining or failing to protect individuals who claim a homosexual identity. Once a soldier steps out of the closet, she or he can be discharged; the rule works to keep homosexuality covered. But just as rules that proscribe prostitution influence all women's conduct, those that proscribe sodomy or permit discrimination against homosexuals operate against everyone. The fear of being mistaken for gay encourages "straight" appearance and behavior in all types of people. This fear also discourages gay/straight alliances, since support for homosexual rights might be mistaken for homosexual conduct.

For both Frug and Halley, then, the law creates and defines "woman" or "homosexual" or "heterosexual" even as it restricts and punishes particular conduct. While Frug is interested in the plight of the prostitute and Halley is concerned with the homosexual, their analysis reaches much further. For both of them, legal rules and doctrine "matter," in that they have serious consequences for all of us. By policing the margins, the rules reinforce a normative core.

Dan Danielsen's exploration and comparison of cases about pregnancy and homosexuality takes a slightly different route. He uses the courts' conflicting and contradictory images of gender and sexual orientation— and their relationship to pregnancy and sodomy—to demonstrate the indeterminacy of these categories. But rather than concentrating on the disciplining effect of legal definitions of identity, Danielsen focuses on the ways that images of gender or sexuality generated by the courts mirror those produced in the rest of society, even by people who happily or unhappily find themselves pregnant or gay. Pointing out that women and homosexuals differ among themselves in their perceptions of their own identities, he concludes that we should not expect to find one doctrinal solution or strategy that will guarantee positive political outcomes for women and homosexuals (assuming that we could even agree on what such an outcome might be).

Danielsen does not end on a pessimistic note. Rather, he argues that there is more room in law for multiple and complex images of sexual identity than appears on first reading of the cases he discusses. Consequently, the law is an important site for cultural struggles over the meanings of identities. Danielsen ends his article with a quotation from Mary Joe Frug, bringing the chapter (perhaps a little too neatly) full circle. He cites Frug for her focus on the semiotic nature of sex differences and for her assertion that exposing those differences can affect legal power. Halley would probably agree. Were we better to understand the semiotic nature of the heterosexual/homosexual divide, we would probably be more open to different possibilities for defining/expressing our sexualities.

Frug, Halley and Danielsen all see legal rules and discourse as crucial sites for grappling with identity. They do not contend, however, that law should (or even could) help us find our "true selves." Rather, they suggest it is through interpretive struggles over the meaning of sexuality in law that we participate in the production of our selves in culture.

Chapter One

A Postmodern Feminist Legal Manifesto

(An Unfinished Draft)

Mary Joe Frug

Preliminaries

I AM WORRIED about the title of this article.

Postmodernism may already be passé, for some readers. Like a shooting star or last night's popovers, its genius was the surprise of its appearance. Once that initial moment has passed, there's not much value in what's left over.

For other readers, postmodernism may refer to such an elaborate and demanding genre—within linguistics, psychoanalysis, literary theory, and philosophy—that claiming an affinity to "it" will quite properly invoke a flood of criticism regarding the omissions, misrepresentations, and mistakes that one paper will inevitably make.

The manifesto part may also be troublesome. The dictionary describes a manifesto as a statement of principles or intentions, while I have in mind a rather informal presentation; more of a discussion, say, in which the "principles" are somewhat contradictory and the "intentions" are loosely formulated goals that are qualified by an admission that they might not work. MacKinnon, of course, launched feminism into social theory orbit by drawing on Marxism to present her biting analysis.1 Referring to one word in a Karl Marx title may represent an acknowledgement of her work, an unconscious, copyKat gesture; but I don't want to get carried away. I am in favor of localized disruptions. I am against totalizing theory.

Sometimes the "PM"s that label my notes remind me of female troubles—of premenstrual and postmenopausal blues. Maybe I am destined to do exactly what my title prescribes; just note the discomfort and keep going.

One “Principle”

The liberal equality doctrine is often understood as an engine of liberation with respect to sex-specific rules. This imagery suggests the repressive function of law, a function that feminists have inventively sought to appropriate and exploit through critical scholarship, litigation, and legislative campaigns. Examples of these efforts include work seeking to strengthen domestic violence statutes, to enact a model anti-pornography ordinance, and to expand sexual harassment doctrine.

The postmodern position locating human experience as inescapably within language suggests that feminists should not overlook the constructive function of legal language as a critical frontier for feminist reforms. To put this "principle" more bluntly, legal discourse should be recognized as a site of political struggle over sex differences.

This is not a proposal that we try to promote a benevolent and fixed meaning for sex differences. (See the "principle" below.) Rather, the argument is that continuous interpretive struggles over the meaning of sex differences can have an impact on patriarchal legal power.

Another “Principle”

In their most vulgar, bootlegged versions, both radical and cultural legal feminisms depict male and female sexual identities as anatomically determined and psychologically predictable. This is inconsistent with the semiotic character of sex differences and the impact that historical specificity has on any individual identity. In postmodern jargon, this treatment of sexual identity is inconsistent with a decentered, polymorphous, contingent understanding of the subject.

Because sex differences are semiotic—that is, constituted by a system of signs that we produce and interpret—each of us inescapably produces herself within the gender meaning system, although the meaning of gender is indeterminate or undecidable. The dilemma of difference, which the liberal equality guarantee seeks to avoid through neutrality, is unavoidable.

On Style

Style is important in postmodern work. The medium is the message, in some cases—although by no means all. When style is salient, it is characterized by irony and by wordplay that is often dazzlingly funny, smart, and irreverent. Things aren't just what they seem.

By arguing that legal rhetoric should not be dominated by masculine pronouns or by stereotypically masculine imagery, legal feminists have conceded the significance of style. But the postmodern tone sharply contrasts with the earnestness that almost universally characterizes feminist scholarship. "[T]he circumstances of women's lives [are] unbearable," Andrea Dworkin writes.2 Legal feminists tend to agree. Hardly appropriate material for irony and play.

I do not underestimate the oppression of women as Andrea Dworkin describes it. I also appreciate what a hard time women have had communicating our situation. Reports from numerous state commissions on gender bias in the courts have concluded that one of the most significant problems of women in law is their lack of credibility. Dworkin puts this point more movingly:

The accounts of rape, wife beating, forced childbearing, medical butchering, sex-motivated murder, forced prostitution, physical mutilation, sadistic psychological abuse, and other commonplaces of female experience that are excavated from the past or given by contemporary survivors should leave the heart seared, the mind in anguish, the conscience in upheaval. But they do not. No matter how often these stories are told, with whatever clarity or eloquence, bitterness or sorrow, they might as well have been whispered in wind or written in sand: they disappear, as if they were nothing. The tellers and the stories are ignored or ridiculed, threatened back into silence or destroyed, and the experience of female suffering is buried in cultural invisibility and contempt.3

Although the flip, condescending, and mocking tones that often characterize postmodernism may not capture the intensity and urgency that frequently motivate feminist legal scholarship, the postmodern style does not strike me as "politically incorrect." Indeed, the oppositional character of the style arguably coincides with the oppositional spirit of feminism. Irony, for example, is a stylistic method of acknowledging and challenging a dominant meaning, of saying something and simultaneously denying it. Figures of speech invite i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART ONE: SEXUALITY

- PART TWO: AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

- PART THREE: COMMUNITY

- PART FOUR: POSTCOLONIALISM

- PART FIVE: VIOLENCE

- Index

- Permissions

- Notes on Contributors