![]()

Part I

Biographical-Historical

![]()

Introduction

Part I provides a biographical-historical foundation for understanding Ferenczi’s psychoanalytic contributions most fully. In this section, we get an overview of Ferenczi’s personal and professional life, from its beginnings to its end, and trace the evolution of Ferenczi’s thinking within this context. We see the places and meet some of the important people—family, friends, colleagues, patients—that shaped him as a person and contributed to the development of his ideas. We learn of his role in developing the institutions of organised psychoanalysis, and read of his presence in the Hungarian popular press.

Krisztián Kapusi starts us off with a guided tour of the Miskolc that Sándor Ferenczi grew up in—the “Middle-European middle-town” of the late nineteenth century, behind its current-day incarnation. Kapusi recreates for us the sights and sounds of the family bookstore and the street where Sándor lived, invites us along on Sándor’s daily morning walk to the high school from which he graduated in 1890 (as well as on some detours), introduces us to Sándor’s parents, and reconstructs various notable moments in the life of his family and hometown.

Next, we follow Tom Keve to the Budapest Ferenczi discovered after moving there on completing his medical training in Vienna—a vibrant boomtown, modeled after Paris and about to celebrate the Hungarian Millennium, which had not long before become the second capital of an empire. He draws back the curtain on the thriving cultural, artistic, and intellectual life that became Ferenczi’s world during the years that spanned the fin-de-siècle, the tragic consequences of the rapid-fire political revolutions and antisemitism that followed the end of the Great War, and the city’s partial recovery despite political threats at home and beyond Hungary’s borders.

Gabriele Cassullo then surveys Ferenczi’s “pre-psychoanalytic” writings, showing how many of Ferenczi’s later psychoanalytic interests were already present in this early work: the mind-body connection; unconscious interpersonal communication and mutual influence in the therapy relationship; appreciation of the essential role of the physician’s honesty, sincerity, and humility, and of trust, in healing; the role of omnipotent fantasies, and their disillusionment, in psychic life and development; and a social-reformist zeal.

Louis Breger tracks the development of the Freud-Ferenczi relationship, emphasising Ferenczi’s painful struggle, especially toward the end of his life, to pursue his own clinical discoveries, and the theoretical ideas to which they led him, against the strong tide of Freud’s authoritarian control.

Carlo Bonomi explores Ferenczi’s analyses—plural—with Freud. He traces these through Ferenczi’s self-analysis, the correspondence and overall relationship between these two men, as well as the formally designated analysis of Ferenczi by Freud—all analytic, and interrelated in complex ways. Bonomi emphasises the unresolved emotional conflicts, ambivalences, projections, and disavowals in Freud, not just in Ferenczi, that shaped their relationship; the distorting influence of Freud’s intrusive entanglements with important people in Ferenczi’s life, and of Freud’s agenda regarding Ferenczi’s role in the psychoanalytic movement; and Ferenczi’s sacrificial responsiveness even to Freud’s unacknowledged pressure.

Emanuel Berman provides a wealth of primary-sourced information, and a thoughtful, compassionate meditation, on the knotty and inauspicious web of relationships between Ferenczi and his future wife Gizella; her daughter Elma, who Ferenczi took on as a patient and also fell in love with; and Freud, who, for a while, took over Elma’s treatment, though with discretion and neutrality notably absent. We hear directly from the participants about their struggles during this painful episode. Berman concludes by discussing ethical issues that can arise from the unavoidable impact of the analyst’s subjectivity on the patient, and from analysts’ approach to power relations and boundaries within the analytic relationship.

Ernst Falzeder explores Ferenczi’s personal correspondence with colleagues, noting that the Ferenczi who emerges from his letters, to Freud and to others, often defies “the various pigeonholes into which he has so often been stuck.” Ferenczi strove for a high level of mutual understanding, honesty, and openness in his correspondence, yet he could also be withdrawn and aloof. He struggled between orthodoxy and dissidence. For Falzeder, as for many of us, it’s easy to see Ferenczi’s humanity in his letters, and to like him.

Janos Harmatta takes us through the twists, turns, and political minefields that had to be navigated in the founding and early evolution of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA). He also describes the early history of the Hungarian Psychoanalytical Society. While Ferenczi had a founding role in the history of both organisations, and was elected president of the IPA at the end of the First World War, he held this role only briefly, due to communication difficulties created by the collapse of the Empire. Perhaps ironically, he turned down Freud’s offer of the IPA presidency late in his life, largely in order to preserve his freedom to pursue interests that diverged from what was acceptable to Freud and the psychoanalytic mainstream.

Anna Bentinck van Schoonheten traces out Ferenczi’s place in the social and professional world of early psychoanalysis, from the lead-up (with Jung as intermediary) to Ferenczi’s first meeting with Freud, and their fast-blossoming, intimate, and increasingly conflictual relationship; through Ferenczi’s clumsy efforts to establish the International Psychoanalytical Association, and his later disappointments as he pursued its presidency; his idea to establish the “secret committee” that successfully pushed Jung out of psychoanalysis; and his relationships with the committee’s other members, most notably his complicated, increasingly sour connection with Jones, and his political struggles with Eitingon.

Next, Ferenczi’s studies of war neurosis, based upon his experience treating war-traumatised soldiers during the First World War, are examined by Andreas Hamburger. Hamburger explores the historical context of these studies on several different levels—the circumstances surrounding Ferenczi’s attention to war neurosis, the psychoanalytic-political situation at the end of the war and the reception Ferenczi’s war-neurosis work received within psychoanalysis, the place of Ferenczi’s discoveries in the development of his trauma theory, and the relationship of the contemporary interest in trauma studies to our current zeitgeist. Hamburger also describes Ferenczi’s clinical discoveries about war neuroses—most notably, that they result from psychological causes, specifically from narcissistic injury.

Melinda Friedrich unearths Ferenczi’s writings in the popular press. Based upon her research into a trove of information largely unknown to contemporary Ferenczi scholars, Friedrich informs us that Ferenczi was an active presence in Budapest’s popular press. His lectures were advertised and reported in detail, and he presented his opinions on issues of the day, about psychology and related medical and scientific matters but also political questions, in publications across the political spectrum. Friedrich offers fascinating morsels of what Ferenczi had to say in his press interviews.

Christopher Fortune describes Ferenczi’s relationship with Georg Groddeck, a most intimate friend, personal physician, and in various senses an analyst to Ferenczi, during the last dozen years of Ferenczi’s life. Groddeck was a unique figure in the psychoanalytic movement, marginal yet important—a free-thinking self-described “wild analyst” who explored mind-body connections, the psychological treatment of organic disorders, and the importance of early trauma and the mother: all interests he shared with Ferenczi. Perhaps most important, he played a key role in helping Ferenczi develop his own autonomous voice within psychoanalysis.

B. William Brennan gives a detailed overview of Ferenczi’s patients, especially those Ferenczi wrote about in his Clinical Diary. Brennan, based on his own groundbreaking research, identifies the real people whom Ferenczi disguised by code letters in the Diary, giving us brief sketches of their lives, and describing the often-intimate interrelationships among the members of what was essentially a group of expatriate Americans who had come to Budapest to be analysed by Ferenczi. Brennan also tells us about many of the other patients Ferenczi worked with over the years, locating them socially and, for his many patients who were also analysts, professionally.

Éva Brabant-Gerö and Judith Dupont-Dormandi tell us some things we may want to know before reading Ferenczi’s Clinical Diary. Brabant prepares us for how we may feel as we witness, through the Diary’s pages, Ferenczi’s intimate struggles with his own traumas and with Freud’s painful inability or refusal to understand Ferenczi’s radically new, intersubjective, trauma-based view of psychoanalysis—a perspective that has become foundational for twenty-first-century psychoanalysis. Then Dupont, editor of the Diary and Ferenczi’s former literary executor, takes us through the difficult history of its half-century delay in publication, and the personal engagement necessary if a reader is to take in most fully the human and clinical insights it offers.

Lastly, Peter Hoffer offers a detailed account of Ferenczi’s final illness and death against the background of an emotionally strained, increasingly tense relationship with Freud. And Hoffer lays out a dispassionate examination of the still-controversial question of Ferenczi’s mental deterioration during the final stages of his illness.

With the biographical-historical foundation of this first section of the book in place, we will be well positioned to approach Ferenczi’s clinical and theoretical contributions, the topic of the book’s second section.

![]()

Chapter 1

Amidst hills, creeks and books Sándor Ferenczi's childhood in Miskolc

Krisztián Kapusi

Middle-European middle-town. It would be irremediably average, even with its eclecticism, if it had a main square, if it still had its uniform architecture, if its firewalls didn’t stick out left and right over the neighbouring rooftops, and it weren’t irreparably wrinkled and broken. An old church with ringing bells, a theatre portico, clanking tram. The main street rises from the east, its dual curvature resembling a human spine: at its lower vertebrae, the city’s skeleton, that is, the eastern portion bends in a careful arch; at the top, however, from the Sötétkapu (Dark Gate), it turns sharply toward its head, the town hall. From the summits of the Bükk Mountains, ridges, opening like compasses, accompany the Szinva stream’s Miskolc valley to the Great Hungarian Plain. From the south, the foot of the Avas hill closes off the double folding screen of viticulture at the foot of the mountain. From the north, in turn, Tetemvár is the final element of the ridge reaching the lowlands. These noticeable slopes indicate downtown Miskolc to the traveller on the highway. Instead of the scions of bourgeois guild families, it is almost always others who inhabit it, therefore there are no tarnished signs, legendary stores, and dynasties, like those of the Austrians or the Czechs. Instead, rows of banks and telephone stores, all sorts of cheap Chinese clothing, Balkan bakeries, Arab kebabs. Nowadays, you have to explain where Miskolc’s first bookstore stood, operated by the Ferenczi family.

Days, weeks, months: between 7 July 1873 and September 1890, a Miskolc kid grows up. He roves the central streets; climbs the neighbouring hills; breathes the air of households, stores, squares; knows the lights and shadows of the alternating seasons. Lives the city, with memories tied to each and every nook and cranny.

On Miskolc’s main street, (Széchenyi Street, numbers 11–13), in place of a modern multistory brick building, stood the Ferenczi bookstore. It was built sometime in the second half of the eighteenth century by Greek merchants in the Baroque style. Ferdinánd János Groszman opened Miskolc’s first bookshop in this greenish-yellow house built from heavy sandstone, in 1835. Groszman went bankrupt, so in 1847, Mihály Heilprin, the learned poet of the war of independence, the secretary of the ministry of the interior, re-established the bookstore. Due to his past as a revolutionary, he left for America in the years of neoabsolutism. In 1856 the store was taken over by Bernát Fraenkel (his brother in law’s brother, specifically the younger brother of his little sister’s husband), who later, in 1879, Magyarised his name to Ferenczi. Locally, in Miskolc, his store became a legend. Worldwide, his eighth child, Sándor Ferenczi became famous. He made their family name, was known as Sigmund Freud’s disciple, and revolutionised Hungarian psychotherapy.

The estate, opening on to the main street, was fairly narrow, ten to fifteen metres wide, but its length, which extended to the Pece stream, was nearly one hundred metres. Made up of 315 squares, its area was about 1130 square metres. Its front, looking on to the promenade, completely filled the building. Next to the bookstore, spanning the ground floor, on the eastern side of the facade, a driveway through a wrought iron gate led into the courtyard. The stairwell leading to the living quarters was to the left, under the driveway. There were three windows on the top floor, above the bookstore’s display and sign-board (“B. Ferenczi bookshop, Founded 1835”), then two more on the level of the driveway, so altogether five windows looked on to the Sötétkapu across the way. Behind the bookshop and the living quarters, there was plenty of usable area; tenants lived in the buildings in the yard and various businesses were operated there (in 1911, for example, a laundry, a carpenter, and a locksmith).

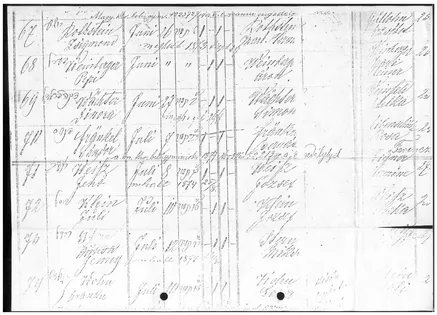

Miskolc birth registry from 1873, with entry “Fraenkel, Sandor” courtesy Judit Meszaros

The iron door creaks. Teenaged Sándor Ferenczi steps out on to the main street, on the way to school. Across from their house, the Dark Gate swallows him; he still turns around and sees that the neighbouring “Pharmacy to the Hungarian Crown” (Széchenyi Street, number 11), is getting ready to open. It’s time. He has to pick up his pace.

He speeds up on Püspök (today, Rákóczi) Street, clanging across the Szinva Bridge. He turns to the right, that is, to the west. Another sixty to eighty metres and he reaches the Reformed Church high school’s building (today, Papszer Street, number 1). He attends a sombre, several-hundred-year-old school, which is not old-fashioned, in spite of its patina.

Due to the damages of the great Miskolc flood (30 August 1878), the building is renovated a few ye...