- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Examines the history of evolutionism in cultural anthropology, beginning with its roots in the 19th century, through the half-century of anti-evolutionism, to its reemergence in the 1950s, and the current perspectives on it today. No other book covers the subject so fully or over such a long period of time.. Evolutionism and Cultural Anthropology traces the interaction of evolutionary thought and anthropological theory from Herbert Spencer to the twenty-first century. It is a focused examination of how the idea of evolution has continued to provide anthropology with a master principle around which a vast body of data can be organized and synthesized. Erudite and readable, and quoting extensively from early theorists (such as Edward Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, John McLennan, Henry Maine, and James Frazer) so that the reader might judge them on the basis of their own words, Evolutionism and Cultural Anthropology is useful reading for courses in anthropological theory and the history of anthropology. 0813337666 Evolutionism in Cultural Anthropology : a Critical History

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evolutionism In Cultural Anthropology by Robert L. Carneiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Early History of Evolutionism

Before dealing with cultural evolutionism proper, it seems useful to sketch briefly the history of the general notion of evolution. The word "evolution" itself derives from the Latin evolūtio, from e-, "out of," and volūtus, "rolled." It meant, literally, an unrolling, and was applied especially to the opening of a book. Roman books were written on lengths of parchment and rolled onto wooden rods, so that to be read they had to be unrolled or "evolved" (McCabe 1921:2).

In the seventeenth century, evolution began to be used in English to refer to an orderly sequence of events, particularly one in which the outcome was somehow contained within it from the start. This use of the word reflected the prevailing philosophical notion of the nature of change. It had been widely believed, at least since the time of Aristotle, that things changed in accordance with an inner principle of development. This principle was sometimes thought to be embodied in a seed or germ. Gottfried Leibniz called these germs "monads," and thought that encapsulated within them were all the characteristics that objects animated by them would eventually reveal (Leibniz 1898:44n., 373, 419). Moreover, the development or unfolding of a monad was, for Leibniz, largely a matter of the operation of internal forces; surrounding conditions played little or no role (1898;44n., 105).

This view of the nature of change was widespread in European philosophy during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Immanuel Kant, for example, spoke of the "germs. . . implanted in our species [by Nature]" as being "unfolded to that stage of development which is completely conformable to her inherent design" (Kant 1969:52-53). And Georg Hegel wrote that "the principle of Development involves the existence of a latent germ of being—a capacity or potentiality striving to realize itself (Hegel 1956:54). And he, too, viewed this development as not affected by external influences, but rather as one "which expands itself in virtue of an internal unchangeable principle" (1956:55).

Well into the nineteenth century, then, the prevailing conception of evolution was, as Arthur Lovejoy expressed it, that "the 'germs' of all things have always existed . . . [and] contain within themselves an internal principle of development which drives them on through a vast series of metamorphoses through which they ascend the 'universal scale'" (Lovejoy 1936:274).

It was in this sense that the term evolution was first used in biology by Charles Bonnet in his Considérations sur les Corps Organisés (1762). Being a "preformationist," Bonnet believed that all parts of the embryo were already completely formed before conception, and that prenatal development consisted only of the unfolding and expanding of a preexistent germ. It was to this supposed process that Bonnet applied the term "evolution." In his usage, "evolution" was opposed to "epigenesis," the doctrine that held that the ovum and the sperm contained none of the physical features of the developed adult, but that these arose only gradually after fertilization (Osborn 1927:118-121; Fothergill 1952:45-46; Miall 1912:289-290).

Perhaps it was because the term evolution still retained something of this notion of preformation that Jean-Baptiste Lamarck failed to use it in 1809 in his famous work Philosophie Zoologique, the first serious biological treatise to affirm the theory of the transmutation of species.

"Evolution" was, however, used freely by Auguste Comte in his Cours de Philosophie Positive (6 vols., 1830-1842) and again in his Système de Poli-tique Positive (4 vols., 1851-1854). Comte gave the term no explicit definition, but used it in the general sense of progress or growth, without implying that the end product of evolution was always, or necessarily, contained in its beginnings.

Until the 1850s the use of the word "evolution" was relatively uncommon in England. Thus, when John Stuart Mill, a follower of Comte, wrote A System of Logic in 1843, in which he, like his predecessor, dealt with the possibility of a science of history, he employed the term only once (Mill 1846:578).

In the 1850s, the word evolution began to appear more commonly, but still generally retained the old idea of an unfolding of something immanent. For example, the American theologian William G. T. Shedd, who used the term some forty times in his Lectures upon the Philosophy of History, wrote: "The progressive advance and unfolding which is to be seen all along the line of a development, is simply the expansion over a wider surface of that which from the instant of its creation has existed in a more invisible and metaphysical form" (Shedd 1857:27; see also pp. 18, 26).

Herbert Spencer and the Concept of Evolution

A definition of evolution that was both rigorous and nonmetaphysical was not formulated until around the end of the 1850s. It is generally supposed that the first person to offer such a definition was Charles Darwin. But this supposition is incorrect. The word evolution, as such, does not even appear in the first five editions of The Origin of Species. Not until the sixth edition, in 1872, did Darwin employ the term. And then he used it only half a dozen times, without any specific definition (Darwin 1872:201, 202, 424; Peckham 1959:264, 265, 751).

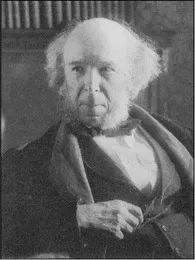

The reason Darwin finally decided to use "evolution," after first ignoring it, was that by 1872 the term, in a scientific sense, had gained wide currency. And the man who had given it that currency was Herbert Spencer. When Spencer first began to deal with evolution, the term was still obscure. He stripped it of its metaphysical elements, defined it with "almost mathematical . . . precision" (Allen 1890:2), demonstrated its universal application, and left it as the guiding principle of all the historical sciences.

Herbert Spencer

Let us see how the concept of evolution developed in Spencer's hands. His first use of the term seems to have been in Social Statics (1851). As far as I have found, he used the word only once here (on p. 440) and made no attempt to define it. He applied it to those kinds of changes in society that he spoke of more frequently as progress (e.g., on p. 63), and meant by it only development in the general sense. No more specific meaning was given to the term. Nevertheless, it is clear that Spencer already held a nonmetaphysical view of evolution as it applied to society, for elsewhere in Social Statics he wrote that "civilization no longer appears to be a regular unfolding after a specific plan; but seems rather a development of man's latent capabilities under the action of favourable circumstances" (Spencer 1851:415). At that time, then, Spencer paid no special attention to the term evolution. In 1852, when he wrote his famous essay The Development Hypothesis, he used the term only once, and merely as a synonym for "development" and "transmutation" (Spencer 1891a: 1 ). All three terms were applied to the gradual transformation of species, which Spencer, seven years before Darwin, openly espoused in opposition to the doctrine of special creation.

In the years immediately following 1852, Spencer continued to concern himself with changes in natural phenomena. His writings for those years show the concept of evolution gradually taking more definite shape, and becoming elaborated in two ways. First, Spencer discerned additional aspects of the evolutionary process itself, and second, he saw evolution as being manifested by more and more classes of phenomena.

Increase in complexity, generally thought of as the hallmark of the Spencerian concept of evolution, was suggested to Spencer by reading Karl E. von Baer's observation that embryological development proceeded from homogeneity to heterogeneity (Spencer 1926:I, 384). In various articles published in the mid-1850s, Spencer traced this change toward progressively greater complexity in a number of discrete phenomena, such as manners, fashion, government, science, etc. ( 1896:II, 9-11). Then in "Progress: Its Law and Cause," published in 1857 and a landmark in the history of evolutionism, Spencer generalized the evolutionary process to the entire cosmos:

The advance from the simple to the complex, through a process of successive differentiations, is seen alike in the earliest changes of the Universe to which we can reason our way back; and in the earliest changes which we can inductively establish; it is seen in the geologic and climatic evolution of the Earth, and of every single organism on its surface; it is seen in the evolution of Humanity, whether contemplated in the civilized individual, or in the aggregation of races; it is seen in the evolution of Society in respect alike of its political, its religious, and its economical organisation; and it is seen in the evolution of all. . . [the] endless concrete and abstract products of human activity. (Spencer 1857:465)

In 1858 Spencer conceived the idea of surveying the fields of biology, psychology, sociology, and morals from an evolutionary perspective. In its original draft this plan included one volume to be entitled The Principles of Sociology. By 1860 Spencer's scheme had crystallized further, and he issued a prospectus announcing the future publication of what came to be known as the "Synthetic Philosophy." In this prospectus Principles of Sociology had been expanded to three volumes, which would deal, Spencer wrote, with "general facts, structural and functional, as gathered from a survey of Societies and their changes: in other words, the empirical generalizations that are arrived at by comparing the different societies, and successive phases of the same society" (Spencer 1926:11, 481).

Thus, before any other of the classical evolutionists had published on the subject, Spencer already had a clear notion of a comparative science of society based on evolutionary principles.

The initial volume of Spencer's "Synthetic Philosophy," which appeared in 1862, was First Principles. In this work Spencer devoted a great deal of attention to the concept of evolution, and, step by step, carefully built up to his formal definition of it:

Evolution is a change from an indefinite, incoherent homogeneity, to a definite, coherent heterogeneity; through continuous differentiations and integrations. (Spencer 1863:216)

By 1862, then, Spencer had formulated an explicit, objective, unequivocal, and general concept of the process of evolution.

While in First Principles Spencer presented examples of how evolution had manifested itself in nature generally, he left to The Principles of Sociology (3 vols., 1876-1896) the detailed exemplification of how evolution had occurred in human societies.

The Evolutionary Views of Tylor and Morgan

Here we may leave our examination of evolution as a general process and see how the concept was applied in the emerging science of anthropology. We may begin by comparing the Spencerian formula of evolution with the concepts held by the other two major cultural evolutionists of the nineteenth century, Edward B. Tylor and Lewis H. Morgan,

In the preface to the second edition of his Primitive Culture, Tylor wrote as follows:

It may have struck some readers as an omission, that in a work on civilization insisting so strenuously on a theory of development or evolution, mention should scarcely be made of Mr. Darwin and Mr. Herbert Spencer, whose influence on the whole course of modern thought on such subjects should not be left without formal recognition. This absence of particular reference is accounted for by the present work, arranged on its own lines, coming scarcely into contact of detail with the previous works of these eminent philosophers. (Tylor 1920:I, vii)

And Tylor was right. Primitive Culture was a very different work from Principles of Sociology. As Alexander Goldenweiser was to observe, "When compared with the first volume of Spencer's [Principles of] Sociology, Tylor's classic work, Primitive Culture, was less a contribution to evolutionary thinking than an attempt to trace the life history of a particular belief, namely, animism" (Goldenweiser 1925a:216). Indeed, throughout much of his published work, especially his earlier writings, Tylor showed himself to be a good deal more of a cultural historian than an evolutionist. His concern was largely with tracing the history of myths, riddles, customs, games, rituals, artifacts, and the like, rather than with laying bare the general process or stages in the evolution of culture as a whole.

Though Tylor did use the term evolution (e.g., 1871:I, 1, 22, 62; II, 401, 406, 408), he did so sparingly, and attempted no formal definition of it. Moreover, he applied it to almost any succession of specific forms, and did not restrict the concept to changes involving increased heterogeneity, definiteness, or integration, as Spencer had.

The contrast between Spencerian evolutionism and Tylorian historicism appears most strikingly in a little-known article by Tylor entitled "The Study of Customs." This article, which appeared in 1882, was a review of "Ceremonial Institutions," a part of Volume 2 of Spencer's Principles of Sociology. Some years before, Tylor had engaged in a long and bitter controversy with Spencer over priority in originating the theory of animism, and he took this opportunity to assail Spencer once more, criticizing him severely for offering conjectural explanations of certain ceremonial practices.

For example, noting that high-order samurai in Japan wore two swords, Spencer had suggested that the second sword represented one taken as a trophy from a fallen enemy, and later worn as a badge of honor. But by a more thorough study of the sources, Tylor was able to show that Spencer was wrong. The two swords worn by a samurai were different types of weapons. The short waki-zashi served to cut and thrust at close range, whereas the longer katana, which was unsheathed with a great sweep, was used to attack enemies at a greater distance.

Tylor proceeded to challenge Spencer's interpretations of the origins of handshaking, tattooing, the wearing of black in mourning, etc., offering his own explanations of these practices. These explanations strike the reader as sounder and more convincing than those offered by Spencer, and appear to be based on a broader and deeper knowledge of the documentary evidence.

Tylor thus revealed himself to be better acquainted with the historical sources, and more critical in handling them, than did Spencer. But at the same time that he showed himself a superior cultural historian, Tylor also revealed the limitations so often associated with historical particularism. His concern with the minute details of culture history arrested his attention and kept him from grappling with the broader problems of the evolution of sociocultural systems. Thus, although Tylor's work was generally sounder than that of Spencer, it was also narrower. Venturing less, he achieved less. His evolutionism, such as it was, was of the limited Darwinian sort, that is, descent with modifications, and lacked the sweep and power of Spencer's. We might epitomize the two men by saying that Tylor appears to us as a master of facts, Spencer as a master of theory.

Tylor's concern with the history of discrete cultural elements rather than with the evolution of entire social systems is rarely recognized today Yet it was the hallmark of most of his scholarly work, at least during the early and middle years of his career. Not until 1889, when he wrote his famous article "On a Method of Investigating the Development of Institutions," did Tylor attempt to wrestle with more general and systematic kinds of change in human societies.

Like Tylor, Lewis H. Morgan rarely used the term evolution. Indeed, Bernhard J. Stern (1931:23) even claimed that Morgan "carefully avoided" the word, and that "nowhere in his books" does it appear. However, as Leslie A. White (1944:224) has noted, this is not true: "Evolution" appears twice in the first four pages of the Holt edition of Ancient Society. But as White also notes, Morgan did not use the term often, nor did he give it any formal definition. He did, however, speak frequently of "progress," "growth," and "development," seeming to prefer these terms to "evolution." Indeed, as White (1944:224) again points out, each of the four parts of Ancient Society is entitled "Growth of . . .," instead of "Evolution of . . .," as they might hav...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 The Early History of Evolutionism

- 2 The Reconstruction of Cultural Evolution

- 3 The Characteristics of Cultural Evolution

- 4 The Determinants of Cultural Evolution

- 5 Anti-Evolutionism in the Ascendancy

- 6 Early Stages in the Reemergence of Evolutionism

- 7 Issues in Late Midcentury Evolutionism

- 8 Features of the Evolutionary Process

- 9 What Drives the Evolution of Culture?

- 10 Other Perspectives on Cultural Evolution

- 11 Elements of Evolutionary Formulations

- 12 Current Issues and Attitudes in the Study of Cultural Evolution

- References Cited

- Index