- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book examines the role of the international financial system in the development of Pacific Asia and, conversely, the region's growing influence on North America and the world economy. It looks at the distant future, being devoted primarily to understanding the emergence of modern Pacific Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pacific Century by Mark Borthwick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Studi regionali. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

DYNASTIES, EMPIRES, AND AGES OF COMMERCE

Pacific Asia to the Nineteenth Century

QIN: THE FIRST CHINESE EMPIRE

In one of the most vivid scenes to appear in the records of ancient China, the assassin Zhong Ke enters the audience chamber of King Zheng of Qin bearing gifts from the northeastern rival state of Yan. In a box he carries the head of one of Zheng’s enemies and a map showing a gift of territory. Rolled up in the map is a poison dagger, with which Zhong Ke intends to kill the king.

In the midst of his presentation, he grasps the dagger and thrusts at Zheng, who pulls back just in time. The panic-stricken monarch dodges behind a great pillar with the assassin in pursuit. Unarmed courtiers scatter in fright while outside the chamber door the guards hesitate at the sound of the commotion: The king’s strict internal security rules forbid them to enter.

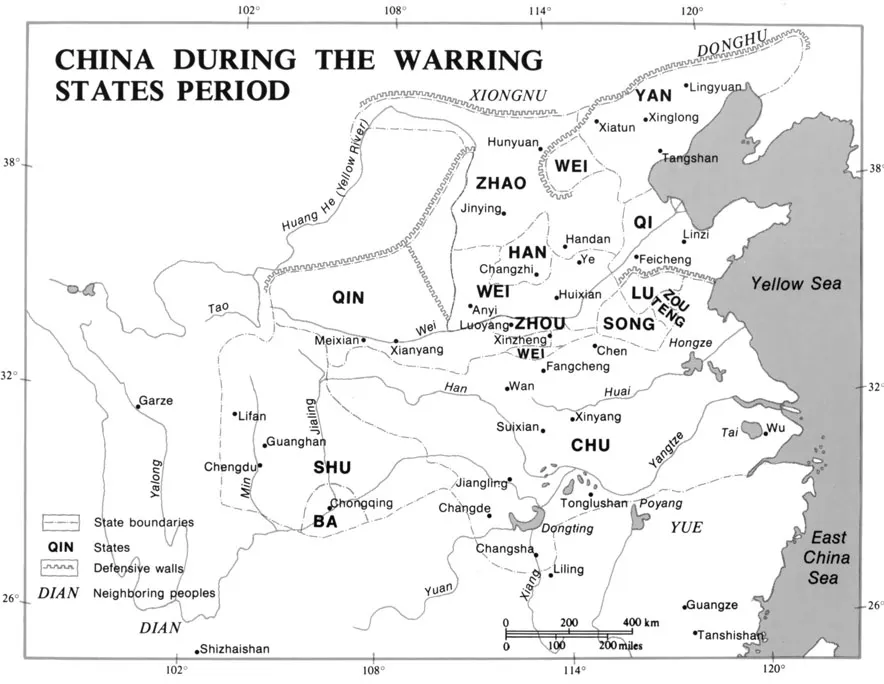

Although unforeseen at the time, much more than a single life or kingdom hung in the balance in this drama. The outcome held immense consequences for the course of China’s history and much of Pacific Asia. At the time, King Zheng was engaged in an effort to unite a conglomeration of feuding kingdoms. During an earlier period of economic and legal reforms, his state of Qin had become one of the best organized and most powerful kingdoms among the Zhou people of the Huanghe (Yellow River) valley, and his military successes had reached a point that caused his rivals to search for every possible means to stop him.

While the assassin lunged at him from the other side of the pillar, King Zheng struggled to draw his long, unwieldy sword. The court physician rushed forward and struck Zhong Ke with his bag. A courtier called out to the king to keep pulling the long scabbard back until at last the king freed his sword and wounded his assailant. Zhong Ke hurled the dagger at the king but instead struck the pillar, and a few moments later the would-be murderer was slain.

Far-reaching events were to unfold with King Zheng’s survival. By 221 BCE he had unified the former Zhou kingdoms and embarked on a series of changes that were to set the character of Chinese dynasties long after his own very brief dynasty (221–206 BCE) came to an end. The region he unified and enlarged acquired the name of his own state, Qin (Ch’in; see appendix 2: “Representation of Foreign Words and Names”), from which its enduring name, China, is derived. The name he took for himself was Qin Shihuangdi (Ch’in Shih Huang-ti), the Qin “First Emperor,” a lofty title that bestowed upon him the unprecedented designation of a ruler who was superior even to the legendary sage kings.

The First Emperor was no sage, but his accomplishments warrant a special place in Chinese history. When he assumed the Qin throne in 245 BCE at the age of thirteen, much had already been achieved in the way of well-codified laws and standardized measurements, practices that he extended throughout the new empire. Aided by key advisers, he established a bureaucracy to govern China in place of a feudalistic landed aristocracy. This opened up Chinese society to greater social mobility and enabled the bureaucracy and army to draw upon the best available talent.

The First Emperor inherited and further developed an advanced Qin military force. So fundamental was his vast army to his empire’s stability that an army of life-size terra-cotta soldiers was buried, rank on rank, next to his great tomb at Xi’an. The living Qin army had much to defend. To the north the nomadic Xiongnu Empire was rising on the Eurasian steppe, posing a constant threat. In response, the First Emperor developed fortifications that were to be extended and rebuilt in later dynasties as the Great Wall.

The Mandate of Heaven

Before his death in 210 BCE, the First Emperor survived two other assassination attempts. Both of these, like the first, assumed that the entire society he governed would be seriously weakened if its supreme leader were eliminated. A great leader in China was thought to possess the quality of De (Te), inherent power and virtue, which infused and made effective the rituals he performed for the continued prosperity of his people. The First Emperor made every effort to reinforce this view among the general populace.

From the time of the more primitive Shang people, predecessors to the Zhou in the period roughly from 1700 to 1100 BCE, the worship of “Heaven” had become paramount in the Chinese religious system. The Zhou called Heaven Tian (T’ien), which referred to “the abode of Great Spirits,” the sky. In the Zhou tradition, the First Emperor bore the title Tianzi (T’ien Tzu), or “Son of Heaven.”

Among all the supernatural forces recognized by the early Chinese, Heaven reigned supreme. It was the ultimate determinant of human affairs. Fundamental to Chinese thought down to the present century has been the view that the head of government is the supreme arbiter between Heaven and Earth. He was said to maintain stability and favorable relations between the two, much as the pillar behind which King Zheng took refuge helped hold together the roof and structure of his palace. An additional, vital notion was added, however, that is generally referred to as the “Mandate of Heaven”: Whenever the beneficence of Heaven was absent (as evidenced by drought, famine, etc.), the ruler was said to have lost his supernatural potency and with it his “mandate” to rule.

Upon such concepts of supreme leadership and authority, the Zhou people had constructed an elaborately graded hierarchy of social ranks and land ownership within several hundred fiefdoms. The heads of these fiefs owed fealty to their emperor.

FIGURE 1.1 Tomb rubbing depicting the assassination attempt against King Zheng of Qin, right, whose sleeve has been torn off. The presentation of an enemy’s head (actually a renegade Qin general) lies in a box on the floor. The assassin, left, has thrown his knife, which has struck the pillar.

Confucius

Three centuries before the rise of Qin, the ancient Zhou system of feudatories became idealized as a model for society by an intellectual named Kong Fuzi or Kong Zhongni, otherwise known as Confucius (551–479 BCE). Because he lived during a period of dynastic decline and disorder (the so-called Spring and Autumn Annals of the late Zhou period), Confucius and other scholars of his day were concerned primarily with the means by which societal stability and order could be restored. Traveling among the various courts of warring rulers, Confucius offered his ideas and counsel but apparently was given no opportunity to put his philosophy into practice through a position of responsibility. Only after his death were his ideas collected by disciples into a single compendium, the Analects (Lunyu), which became a widespread influence during subsequent centuries.

Confucius longed for China to return to the era of the sage kings, rulers who were said to have presided over neatly subdivided and stable domains where each individual was sensitive to his proper station in life. In this philosophy, generally shared among the Zhou people, it was improper for ordinary men to perform rituals to the major cosmic spirits. Instead they were to focus their sacrifices and rituals on their own ancestors and local deities. The origin of this practice, followed in every successive Chinese dynasty, lay with the ancient Shang people.

The realities of the third century BCE were something altogether different from Confucius’s ideal. Amid the general dissolution of the Zhou system, differing schools of thought arose as to how to restore order to chaos. Some of them, grouped today under the term “Legalists,” bade good riddance to the old feudatory system. The Confucian school, on the other hand, called for a return to the past structures and practices of ideal governance. Still others, such as the Daoist philosophers, suggested that no centralized system at all was required, only an understanding of the mysterious, ever present force known as the Dao (T’ao), the Way.

Once the First Emperor had consolidated his victories, the immediate consequence of this dispute was an effort to resolve it forcibly—an altogether typical response in his case. Coming down firmly on the side of the Legalists, he ordered a massive book burning so that the countryside would be rid of all the alternative viewpoints and other “intellectual” pursuits that he deemed to have no value. His own Qin archives and books on “practical” subjects such as agriculture, medicine, and divination were spared, however. The emperor assumed that he was eliminating a source of opposition to the founding of his new dynasty. Thus began the first documented promotion of a “party line,” a pattern that was to be repeated through China’s history to the present day.

FIGURE 1.2 Terra-cotta warrior from the tomb of the First Emperor. Source: Andromeda Oxford Ltd.

A debate between schools of philosophy and religion in ancient China may seem today like an obscure and irrelevant matter, but the intellectual duels of that time were as vital for the future of China as the thrusts and parries of the moment when Zhong Ke sought to kill the man who would be the First Emperor. Fundamentally, the debate was over how to assert proper order in official affairs and in community and family life. For the Confucianists, the solution could be found in sincere, ethical behavior and a strict observance of traditional rules and ceremonies. Harmony, manifest in the behavior of the so-called Superior Man, was for a Confucianist an elegant balance of motives and manners. His motives were to be infused with self-respect, magnanimity, sincerity, earnestness, and benevolence. These qualities may seem at first idealistic and abstract, but each was carefully observed and defined by the Confucianists. Similarly, manners were held to be a direct reflection of motives exemplified by a child’s duty to the family and, above all, to the father. This principle culminated in loyalty to one’s ruler. Such devotion was to be reciprocated (as in the case also of the other senior positions: father, elder brother, etc.) by benevolence, humanity, and gentility.

The political implications of this viewpoint were as potent as that of the “Mandate of Heaven” itself. The Confucianists asserted that the ethical behavior of the ruler would determine the moral and spiritual health of the entire society. Social reforms would begin at the top, not at the grassroots level.

The good life, then, was for the Confucianists a spiritual achievement. It depended on the notion that people are, at heart, good. Given proper leadership, goodness will blossom and harmony will prevail throughout the land.

The Rival Schools

The Legalists, whose view of human nature was grim, scoffed at Confucianist idealism. The individual responds merely to a desire for pleasure and a fear of pain, they said. Society must be governed by strong laws that take advantage of this fact and specify a clear system of rewards and punishments. The Legalists even disdained the Confucianists’ reverence for the traditional past, asserting instead that only the present should serve as the guide to action. They saw the supreme ruler as someone whose influence over society should derive from his office—his stature—rather than from his moral example. Laws should be established that would reinforce that position. Once they were put in place, argued the Legalists, such laws would make the personal actions of the monarch far less relevant to the prosperity of the kingdom. Society—including its total economy—could thus be managed by an application of rigid rules that, for some of the more extreme adherents of Legalism, foresaw the creation of an essentially totalitarian state.

MAP 1.1 Source: Asia Society.

The original Daoist scholars heaped scorn on Confucianists and Legalists alike. Daoists were compilers and students of the Daode jing (Tao Te Ching), a book whose philosophy is derived from statements ascribed to Laozi (Lao Tzu), an older contemporary of Confucius. Whether or not Laozi actually lived in the sixth century BCE as is traditionally assumed, his disciples—particularly the sage Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu)—popularized the teachings. These focus on the nature of the Dao even though it defies any simple definition. In fact, the Dao was acknowledged by its proponents to be indefinable. At bottom, it represents the source of all active power (De) in the universe.

Next to Confucianism, Daoism is the second great, original Chinese tradition that survived all other traditions. Each underwent transformations over the centuries and influenced the other, but the fundamental contrast between them remained throughout: Daoism asserted that the key to all meaning was to be found in the workings of the natural world; Confucianism found such meaning in human relationships. Daoism called for a “letting go” of the Dao so that it and all it embraced would follow a natural course. Confucianism sought to elicit the natural harmony of things but did so by insisting on proper behavior and a far more active role by leaders if society was to be effectively governed.

The debates among these and other schools form an important philosophical base for the next two thousand years of Chinese ideas about society and nature. Confucianism survived the initial “book burning” assault against it by the First Emperor (which was aided and abetted by the Legalists). The Qin Dynasty itself did not survive more than a few years beyond the emperor’s death; his successor was too weak and his rule became too harsh for the society to endure without revolt. Civil war broke out and a new dynasty emerged, the Han, which was to rule China for the next four centuries (206 BCE–221 CE).

The Dao that can be told

Is not the eternal Dao.

The name that can be named

Is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

Ever desireless, one can see the mystery Ever desiring, one can see the manifestations.

These two spring from the same source but differ in name; thus appear as darkness.

Darkness within darkness

The gate to all mystery.

—DAODE JING (TAO TE CHING)

THE HAN DYNASTY AND THE CHINESE LANGUAGE

The Qin and Han Empires conquered new territory that includes much of present-day China. Here began the governing structures of the Chinese state that were to hold sway for nearly two thousand years: an absolute monarch, a council of ministers, and a civil service. The only hereditary aristocracy permitted was that connected with the imperial family. Officials were recommended by an elite group of ministers, and even though the imperial examination system had not yet begun, this sufficed to ensure a high quality of administration. The feudal system of land ownership was abolished, but in its place emerged a new stratification of landlord owners and peasants.

The Han Dynasty fostered the broad distribution of the Chinese language. Written Chinese became widely adopted by literate people all across East Asia who were exposed to Chinese culture. In fact, the term for “civilization” literally means “adopting writing.”

Chinese is a language family within which there are several mutually unintelligible tongues (some would say dialects),1 but its written form was less subject to such regional variations. It can be rendered in variant styles of calligraphy, some of which are beautiful products not only of the tools used but also of the character and spirit of the writer. Each basic unit of meaning is normally represented by a single graph or “character,” with the result that normal communication requires a knowledge of three to four thousand characters. The English language...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface to the 4th Edition

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION

- 1. DYNASTIES, EMPIRES, AND AGES OF COMMERCE: PACIFIC ASIA TO THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

- 2. SEABORNE BARBARIANS: INCURSIONS BY THE WEST

- 3. MEIJI: JAPAN IN THE AGE OF IMPERIALISM

- 4. THE RISE OF NATIONALISM AND COMMUNISM

- 5. MAELSTROM: THE PACIFIC WAR AND ITS AFTERMATH

- 6. MIRACLE BY DESIGN: THE POSTWAR RESURGENCE OF JAPAN

- 7. THE NEW ASIAN CAPITALISTS

- 8. POWER, AUTHORITY, AND THE ADVENT OF DEMOCRACY

- 9. SENTIMENTAL IMPERIALISTS: AMERICA’S COLD WAR IN ASIA

- 10. CHINA’S LONG MARCH TOWARD MODERNIZATION

- 11. BEYOND THE REVOLUTION: INDONESIA AND VIETNAM

- 12. SIBERIAN SALIENT: RUSSIA IN PACIFIC ASIA

- 13. ASIA’S RESURGENCE AND ITS GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS

- Appendix 1: Time Chart: Chronology and Geography in Pacific Asia

- Appendix 2: Representation of Foreign Words and Names

- About the Book and Author

- Index