![]()

One

Greater Siberia: A Resource Frontier

Sibir' tozhe russkaya zemlya (Siberia is also Russian land).

—Old Russian song

Introduction

There is a place so enormous that were it truly independent, it would be the world's largest country; yet, it is treated as a mere appendage of the world's largest country. The old day ends and the new day begins near its eastern margin—the gateway to eight other time zones, the last of which crumpled, along its western margin, against another continent 250 million years ago. It is Asia sutured to Europe. To most mortals, it is a great white void, an arcane, gelid world unto itself. On closer inspection, however, it appears to be many worlds, unified only by the common experience of living on the edge of the earth; or more exactly, many nether worlds—worlds apart from the security and comfort of geographies blessed by moderation and civility.

As geographer Gail Fondahl has observed, Siberia is "people poor," as it is home to a mere 22 percent of Russia's population; but it is simultaneously "peoples rich," with more than thirty different nations staking their claims to its various territories. The peoples who occupy these smaller Siberias are stouthearted and capable of enduring almost any imaginable hardship. More than 400 years ago, one of these peoples, like the Huns of old, chose to conquer and subdue the 200 or more Siberian indigenous tribes then in existence, and thus forever changed the demography of the subcontinent. Today, the aggregate population of native Siberians barely exceeds 4 percent of the total for the region, or approximately 1.3 million people.

Although "Greater Siberia" is many worlds, it is fundamentally two—a pair of enormous moieties, each more than two-thirds the size of the conterminous United States of America. Even though there is a compelling logic for considering them as separate units—as the Russians do—there is also a cogent argument for viewing them as a physical whole, as many Westerners do. As defined in this book, Greater Siberia consists of Siberia proper (Western and Eastern Siberia) plus the Russian Far East. (For the sake of geographic coherence, one might argue for the inclusion of the Urals provinces of Sverdlovsk, Chelyabinsk, and Kurgan, which would expand the region to the continental divide; but convention will not permit us to do this.) On this dual macrocosmic foundation, employing human and physical criteria, we can lay microcosmic brick upon brick— what I call the "little Siberias."

Greater Siberia: Russia's "Foreign Territory"

The Viewpoint

The basic theme of this book is that although the global economy has done without Siberia and can continue to do quite nicely without it, Siberia will languish in isolation from the global economy. Both inside and outside Russia, as Mark Bassin has astutely observed, Siberia traditionally has been considered chuzhaya zemlya (foreign territory).1 Cycles of international interest and disinterest, which have stimulated or retarded regional development, have punctuated the history of Siberia. Although they are worlds apart from the rest of humanity, to flourish, the little Siberias must become an integral part of the global economy.

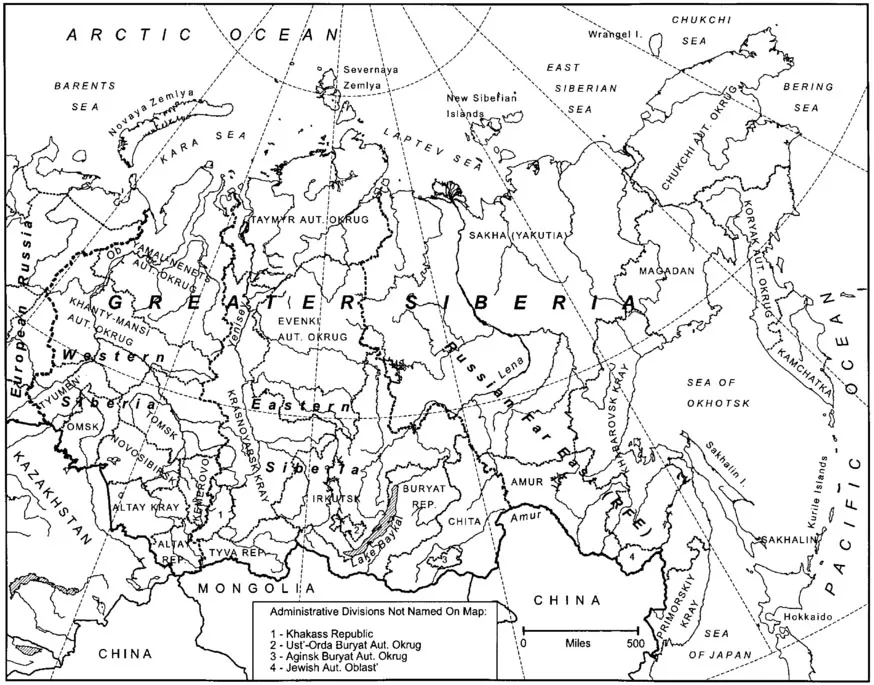

Western Siberia, Eastern Siberia, and the Russian Far East have become acceptable terms of reference in both hemispheres (see Map 1.1); however, these broad and general labels belie the extraordinary diversity that exists within the geography of the regions that they encompass. After six years of post-Soviet collapse, Siberia is no longer a unified whole. In reality, it has never been so. Instead, it always has been composed of numerous, dispersed fragments, held together only by tsarist autocratic rule and Soviet dictatorial terror. Without such glue, the little Siberias might have emerged much earlier. Already, Tyva (formerly Tuva) and Sakha/Yakutia (formerly Yakutia) have taken substantial strides toward economic if not social independence within the Russian Federation. Following their example, the tiny native populations of Chukotka, Khantia-Mansia, and Ya malia have aspired to liberate themselves from the clutches of the provincial authorities of Tyumen' and Magadan, respectively.

The non-Russian titular nationalities are not the only ones threatening to disrupt Moscow's 400-year reign over Siberia. Russian Siberians, too, have demanded regional control over their share of what Russians commonly refer to as "the periphery." For example, during the post-Soviet pe

MAP 1.1 Greater Siberia and the Little Siberias, 1998

riod, developers of the oil and gas fields of Tyumen' and Sakhalin oblasts, the coal miners of the Kuzbas (Kemerovo oblast), and the regional governments of Irkutsk and Primor'ye have taken independent stands on many issues.

A Core and a Periphery

The Russian experience is a cogent example of a core-periphery relationship.2 All countries have cultural and/or economic "cores," which have acquired competitive edges over their surroundings. More often than not, cores consist of a capital city and its immediate hinterland. Readily identifiable examples of such dominant urban systems are London and its sprawling suburbs, Paris and the Paris Basin, New York and "Megalopolis," and Moscow and Moscow oblast. As economic phenomena, cores' relationships with their environments may extend beyond the borders of their respective nation-states. Thus, in the contemporary global economy, the cores of the economically more developed countries largely control the fates of those that are less developed.

In the past, the relationships between cores and their surroundings were colonial in nature. While primary activities such as extractive industries and farming characterized the economies of the areas outside the core, described variously as "peripheries" or "semiperipheries,"3 secondary and tertiary industries typified the cores. The noncores fed the voracious cores with cheap raw materials in exchange for expensive finished products, resulting in a wicked cycle of enrichment of the metropolis at the expense of the colony.4 India's absorption into the British Empire, for instance, was very favorable to Greater London but extremely unfavorable to the "wonderful oriental gentle-subjects" in South Asia. "In the end, India, once a great cotton textile producer, exported only raw cotton to Britain, where it was turned into textile goods and sent back to India to be bought."5

Similarly, the autocrats and commissars of Moscow maintained a policy of economic hegemony over their vast backwaters in Siberia and Central Asia. Although modern Russia is at best semiperipheral within the global economy,6 within the country, the "center," or Moscow and its environs, still reigns supreme over all other space. Russians perceive Moscow as having "everything," and for generations they have done almost "anything" to live there.

In contrast, Siberia is far removed from this fount of Russian development. Subjected to at least passive imperialism for most of its existence, Siberia has been, and is, at the mercy of the Center. Among the many moot definitions of the word Sibir' is "marshy forest."7 From the very beginning of Mongol diffusion (see Chapter 3), therefore, Siberia was identified with its resource base. Even now, Russians view Siberia as a vast "larder" of raw materials, which historically they have exploited irrespective of the consequences.

The Periphery as a Resource Frontier

The establishment of the world economy between 1450 and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s ushered in an "Age of Exploration" not only of the world oceans but also of the great continental interiors. Before 1450, the races were essentially segregated worldwide: Caucasoids in Europe, North Africa, Southwest Asia, and northern India; Mongoloids in the rest of Asia, Madagascar, and the Americas; Negroids in Africa south of the Sahara and a few Pacific islands; and Australoids in Australia and southern India. Three centuries later, European Caucasoids dispersed white civilization to the Americas, Africa, and Oceania; the western hemisphere received boatloads of involuntary migrant Negroids; South Asians established markets in East and South Africa; and the Chinese developed Southeast Asia and Indonesia. Virtually all of these great movements occurred in part or in full via the sea lanes. One conspicuous exception was the expansion of Russians into northern Asia.

Many if not most of these human dispersals laid the groundwork for extensive colonial empires, within the frameworks of which the peripheries represented "resource frontiers." Not the least of these was Greater Siberia. Resource frontiers retreat in the face of expanding civilization. This was the case with the American West: Periphery became semiperiphery, and semiperiphery became part of the core. In Greater Siberia, however, the experience was different. Whereas the American West is no longer valued exclusively for its resources, Greater Siberia remains a salient example of a resource frontier.

Characteristics of Resource Frontiers

In his well-known case study of Venezuela, economist John Friedmann inventoried the characteristics of a resource frontier.8 Based on Friedmann's criteria, Greater Siberia may be the world's quintessential example of this phenomenon.

According to Friedmann, resource frontiers exist because of the finds of major resources, which are developed and supervised by an agency created in the core of the country. The economy of Greater Siberia always has been based on the extraction of raw materials: furs, metals, trees, farm produce, or fossil fuels. Whether in St. Petersburg or Moscow, Russian authorities have dominated the region, and in Soviet times, they commanded it by means of bureaucratic institutions.

Resource frontiers are relatively remote from major centers of consumption, separated by vast expanses of wilderness. Even at its "gateways" (the Urals cities of Chelyabinsk and Yekaterinburg), Greater Siberia is a minimum of 1,750 kilometers (1,075 mi) from the core. Beyond the Urals, except along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, the bulk of the territory is wilderness. The arithmetic density of Greater Siberia is 2.5 persons per square kilometer (6.6 persons per square mile), which makes it more sparsely populated than Libya; moreover, when one considers that 80 percent of the population is concentrated in the southern 15 percent of the region, the northern 85 percent is more sparsely populated than Western Sahara!9

The city is the civilizing agent: Resource frontiers are urban. Although Greater Siberia's overall urban share of 72.4 percent is slightly less than the proportion for the Russian Federation (73 percent), traditionally it has been ahead of the national average. The Russian Far East, at 76 percent urban, is well ahead of that mean, and Magadan and Sakhalin are the most urban provinces in the realm (see Chapter 2). Greater Siberia's settlement system includes 684 settlements of urban type, comprising 208 cities, 24 of which are large urban agglomerations.10 Almost two of three Siberian residents live in a mere 52 cities.

The cities of the resource frontier perform only limited central-place functions because they are isolated; they are also specialized in maintaining the primary resource activity of the area. All except the very largest Siberian cities (Novosibirsk, Omsk, and Krasnoyarsk, for example) are limited in function. Crude frontier settlements, the only purpose of which is to shelter and feed miners and workers, support approximately half of the Siberian population. These settlements are almost always without even the most basic of necessities (such as toothpaste, soap, and detergents).11

The raison d'être of the resource frontier is exports, both regional and international. Resource frontiers import almost everything they consume, while exporting all that they produce. Greater Siberia has been the most important region for the production of Russian exports, and in the Soviet period, Siberia at times accounted for more than half of them.12 The region imports 75 percent of all its machinery, while contributing only 7.4 percent of the total output of Russian machine building and metal fabrication. Less than 2 percent comes from Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East. The latter have always relied on outside regions for 60 percent of their food.

The important export markets often will be foreign, and foreign interests will be committed to the development of the resources. Greater Siberia's share of Soviet exports soared from 18.6 percent in 1970 to 53 percent in 1985, the value exploding from $485 million to $11.2 billion, of which $9.7 billion derived from the sale of West Siberian oil and gas alone. This represented more than half of all Soviet receipts of hard currency.13 Whenever possible during the Soviet period, foreign companies invested heavily in the development of Greater Siberia's oil and petrochemical resources. Since 1991, foreign enterprises have intensively sought toeholds in Asiatic Russian resource development projects.

Communities in res...