- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Hinduism outside the Indian subcontinent represents a contrasting and scattered community. From Britain to the Caribbean, diasporic Hindus have substantially reformed their beliefs and practices in accordance with their historical and social circumstances. In this theoretically innovative analysis Steven Vertovec examines:

* the historical construction of the category 'Hinduism in India'

* the formation of a distinctive Caribbean Hindu culture during the nineteenth century

* the role of youth groups in forging new identities during Trinidad's Hindu Renaissance

* the reproduction of regionally based identities and frictions in Britain's Hindu communities

* the differences in temple use across the diaspora.

This book provides a rich and fascinating view of the Hindu diaspora in the past, present and its possible futures.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Tracing Transformations of Hinduism

In a study on the development of Caribbean Hinduism, Peter van der Veer and I (1991: 149) premised our work with a view that

to be a Hindu is neither an unchanging, primordial identity nor an infinitely flexible one which one can adopt or shed at will, depending on circumstances. It is an identity acquired through social practice and, as such, constantly negotiated in changing contexts.

This assumption holds as much in India as it does in the diaspora.

The following chapter outlines some of the ways in which, and influences by which, Hinduism and Hindu identity have been conceived, negotiated and modified in light of a variety of contexts - historically within the subcontinent as well as outside of it. The chapter sets the stage for the discussion of discrete, often divergent, processes presented in subsequent chapters.

Conceiving Hinduism

A considerable amount of scholarship concerning South Asian history, society and culture has involved detailing or commenting upon the tremendous diversity of what has come to be known as 'Hinduism' in India. Practically every overview of the category Hinduism commences with some comment to the effect that the term includes a vast range of disparate phenomena which - not least because they considerably vary regionally, locally, and in respect of specific caste hierarchies - appear wholly unintegrated with each other. On these grounds Hinduism is often considered to be fundamentally unlike most other 'world faiths'. For instance, W.C. Smith (1964: 61) famously saw 'Hinduism' as 'a particularly false conceptualization'. As Smith put it:

my objection to the term 'Hinduism', of course, is not on the grounds that nothing exists. Obviously an enormous quantity of phenomena is to be found that this term covers ... It is not an entity in any theoretical sense, let alone any practical one.

(ibid.: 63)

In similar terms, Robert E. Frykenberg (1989: 29) states:

there has never been any such thing as a single 'Hinduism' or any single 'Hindu community' for all of India. Nor, for that matter, can one find any such thing as a single 'Hinduism' or 'Hindu community' even for any one sociocultural region of the continent.

Briefly, among the phenomena accounting for such diversity are the following. There is no single, central, or basic creed, doctrine or dogma from which all religious traditions of India derive; instead, 'animism and polytheism, pantheism, panentheism and henotheism, dualism, monotheism and pure monism exist side by side' among a plethora of traditions with 'different views of cosmogony, anthropology and the nature of salvation' (von Stietencron 1989: 14). In relation, there is no scripture that is authoritative for the mass of Indians or for all periods of history, and no central ecclesiastical body holds any parallel authoritative position. Ritual practice, especially, represents a sphere entailing a vast range of difference with regard to focus, intent, and actual undertaking.

Throughout virtually the entire history of Indian civilization, such differentiation of doctrine, authority, and practice has been particularly operative in the religions of relatively discrete social segments, particularly defined by caste, sub-caste and sect (or sampradaya, a tradition focused on a set of beliefs transmitted through a line of teachers). Moreover, language differences, regional histories and provincial customs throughout India combine to produce highly localized religious understandings and practices.

Given such a 'mosaic of discontinuities' characterizing Indian religious traditions (Frykenberg 1989:41), a unitary category encompassing all or most of them could only be arrived at rather artificially. The term 'Hindu' was used by Persians in the first millennium AD to designate generally the people of India (that is, of the region of the river Indus, after which the term derives). 'This all-inclusive term', Romila Thapar (1989: 223) suggests, 'was doubtless a new and bewildering feature for the multiple sects and castes who generally saw themselves as separate entities.' Yet centuries later, after the Mughal civilization had been introduced and developed in India, the indigenous peoples and the Muslim rulers did not see each other in terms of monolithic religious traditions, 'but more in terms of distinct and disparate castes and sects along a social continuum' (ibid.: 225). It was only after the arrival of, and colonization by, Europeans that subsequently the term 'Hinduism' was derived from 'Hindu' by way of abstraction. Hinduism denoted 'an imagined religion of the vast majority of the population - something that had never existed as a "religion" (in the Western sense) in the consciousness of the Indian people themselves' (von Stietencron 1989: 12).

The first attested usage of the word Hinduism in English was as late as 1829 (Weightman 1984). The form and content of the emergent 'ism' since the turn of the eighteenth century to the nineteenth century were variously conceived of or influenced by a number of agents. The most prominent factor in such conceptualization was doubtless the political presence of the British Raj; within this, we can point to at least three major sources which contributed to the construction of Hinduism and an India-wide 'Hindu community'.

The first was Christian missionary activity. Missionaries approached Indian religious traditions as a vast, primitive yet singular complex (Thapar 1989). This was reflected in the missionaries' techniques of preaching, which involved harsh critiques of an assumed 'other faith'. The assumptions and techniques were eventually adopted by Indians themselves struggling, for different reasons, to create a united 'Hindu' community (see Jaffrelot 1992).

Second, nineteenth-century foreign ('Orientalist') scholars assumed Indian heritage to be grounded in a single religion. These scholars worked with theoretical models and categories based on Semitic religions, further equating these categories with historical or evolutionary periods. Many Orientalist scholars were also strongly influenced by early racial theories which mistakenly posited that a single, ancient Aryan people and culture had conquered and had imposed their religion and culture over all of India. By the end of the nineteenth century, Heinrich von Stietencron (1989: 15) notes, 'The Indians had no reason to contradict this: to them, the religious and cultural unity discerned by western scholars was highly welcome in their search for a national identity in the period of struggle for national union.'

The third factor in channelling the conceptual production of 'Hinduism' and a 'Hindu community' in the nineteenth century was the Raj itself. Robert Frykenberg demonstrates, for South India at least,

[how] both the ideological and institutional reification of 'Hinduism', as we now know it (with all its boggy imprecisions), and the construction of something akin to a 'civic' or 'public' religion for India, were parts of a broader political process; and that, as such, when they first began to emerge during the early nineteenth century, they were integral parts of the imperial system engendered by the East India Company.

(1990: 1)

This was effected mainly by way of British laws and other forms of subsuming colonial control (with the assistance of a Brahmin elite) over a range of religious institutions and practices. This, Frykenberg (ibid.: 33) suggests, in turn 'eventually gave rise to a distinct kind of "public" consciousness' among Indians as to what 'Hinduism' might consist of. A 'process of reification' ensued which amounted to 'the defining, the manipulating, and the organizing of the essential elements of what gradually became, for practical purposes, a dynamic new religion' (Frykenberg 1989: 34),

Processes of reification, selection and definition (also of reduction and 'impoverishment'; Gombrich 1992) surrounding the construction of 'Hinduism' and 'Hindu community' also characterize the efforts of numerous indigenous leaders and movements arising in the nineteenth century. Among the most salient are: Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833) and the Brahmo Samaj, who produced a kind of Hindu catechism (an anthology of Upanishads and Smrtis) and sought 'Hindu' parity with Christianity; Dayananda Sarasvati (1824-83) and the Arya Samaj, emphasizing a unitary ancient 'Hindu' heritage based on the Vedas; Ramakrishna (1834-86) and Vivekananda (1863-1902), who both preached a non-sectarian, universalist 'Hinduism'.

The definitions of 'Hinduism' and 'Hindu community' which were promulgated by these figures and movements were appropriated by early regional and pan-Indian nationalists. This appropriation was undertaken since, in India, 'The need for postulating a Hindu community became a requirement for political mobilization in the nineteenth century when representation by religious community became a key to power and where such representation gave access to economic resources' (Thapar 1989: 229).

Sandria B. Freitag (1980, 1989) describes a parallel process stimulated in the competition for resources in colonial India. This entailed, among those eventually to define themselves as Hindus, a 'self-conscious development in opposition to a narrowly defined "Other"' (Freitag 1989: 146). In the 1880s, one important 'Other' was the Arya Samaj, whom many Brahmins and others saw as a threat to their own ritual traditions. The Sanatan Dharm Sabha movement arose in many parts of North India to counter the Arya Samaj's anti-Brahmin, anti-idol, exclusively Vedic doctrines with its own, selective, 'orthodox Hindu' doctrines (see Jones 1976). By the 1920s, Muslims were especially targeted as the 'Other' against which 'Hindus' collectively defined and mobilized themselves.

Throughout the colonial period and through to the present day, Indian religious traditions continue to exhibit the extensive regional, sectarian and caste-based diversity they always have. Yet the homogenizing notions of 'Hinduism' and 'Hindu community' created in rather recent history hold considerable sway throughout Indian society and politics. Hindu nationalism is the obvious result. 'This reifying religious system, combining ideological, institutional, and ritual structures into an "All-India" sense of "patriotism" (or better, "matriotism"), did not need to possess very deep structures', Frykenberg (1990: 35n) comments. 'Indeed,' he observes, 'its selfconscious manifestations within the emerging "public" of India did not even need to be common, or uniform, or held by more than a tiny but creatively influential minority for it to become powerful' (ibid.).

The Hindu nationalist movements which have perhaps had the most impact ideologically are the Hindu Mahasabha, founded in 1909, which claims to promote 'Loyalty to the unity and integrity of Hinduism' (Klostermaier 1989:403); the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) which took shape in 1925 (largely in reaction to Hindu-Muslim riots) in order to work towards 'bridging the differences between different Hindu denominations in the interest of a united, politically strong Hinduism' (ibid.: 406); and, of particular importance in recent years, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) - founded in 1964 as an offshoot of the RSS - which propounds a very broad definition of Hinduism that overrides differences of a doctrinal, organizational, or regional/local nature. The VHP attempts to supply such a definition with 'a centralized form of ecclesiastical organization, matching a more subtle standardization of doctrines and ritual practices' (Jaffrelot 1992: 24; see van der Veer 1994; Jaffrelot 1996; Bhatt 1997).

In addition to these largely political features of nationalist movements, what are the characteristics of the modern concept of Hinduism in India? These are, of course, quite complex, and have been described by numerous social scientists. One widespread trait has been the adoption of the term - as a ready synonym for 'Hinduism' - 'Sanatan Dharm' (sanatan meaning 'eternal', dbarm essentially meaning at once 'cosmic order, sacred duty, mode of being' - though in many quarters it has come to mean 'religion' in a Western sense). Among other characteristics are: a tendency towards rationalization of belief and practice (Bellah 1965); an incorporation of facets drawn from neo-Vedanta philosophy into popular (largely Purana-based) belief (Fitzgerald 1990); an insistence that Hinduism does not essentially differ in nature from Christianity or any other world religion (Bharati 1971); a diminution of beliefs and practices surrounding parochial or so-called 'little traditions' in favour of those of the Sanskritic or 'Great Tradition' (ibid.); and an emphasis on bbakti or loving devotion to God in any form, an orientation which 'inspires not so much sectarian and denominational formations as a diffuse emotion of brotherhood, which softens the rough edges of group differences' (Singer 1971:158). And in keeping with a centralization of the 'Great Tradition' aspects together with bhakti, there seems to be a dominant drive towards Vaishnavism (devotion to Vishnu and his incarnations, particularly Rama and Krishna) as probably the single most prominent orientation in worship.

Further, the modern manifestation of 'Hinduism'

seeks historicity for the incarnations of its deities, encourages the idea of a centrally sacred book, claims monotheism as significant to the worship of deity, acknowledges the authority of the ecclesiastical organization of certain sects as prevailing over all and has supported large-scale missionary work and conversion. These changes allow it to transcend caste identities and reach out to larger numbers.

(Thapar 1989:228)

In the conclusion to her significant article on the development of the concept, Thapar (ibid.: 231) suggests that modern formulations of Hinduism amount to 'communal ideologies [which] may be rooted in the homeland but also find sustenance in the diaspora', Indeed, all of the characteristics discussed above also serve to describe Hinduism as it is usually conceived of by believers outside the subcontinent. However, as in India the ideological formulations of Hinduism in a variety of diasporic locations have been, and continue to be, patterned by a host of unique contextual factors. The following sections explore the background and extent of the Hindu diaspora, some developments that have marked it as well as ways in which we may begin to account for how and why such developments have differed.

The Hindu diaspora: breadth and background

The newspaper Hinduism Today prides itself on a claim to being the voice of 'a billion-strong global religion'. Such a statement is probably rather hopeful. It is currently impossible to gain an accurate count of Hindus, or Indians for that matter, outside India (cf. Clarke et al. 1990a; Peach 1994; Jain 1989). Even in countries in which government censuses include ethnic or country of birth statistics, a census category for religion is usually absent. Intelligent guesses and broad estimates, based on national statistics (while recognizing problems often inherent in these), are the best we can gather to arrive at any kind of picture of the size and extent of the Hindu diaspora.

There is of course a vexed question as to 'who is a Hindu?' The permutations of possible make-up and extent of belief and practice obviously pose important problems of definition which bear on any attempted count of religious adherents (Sander 1997). Aside from a 'religious' meaning, depending on the context, 'Hindu' can refer to an 'ethnic', 'cultural', or even 'political' identity among individuals who do not particularly profess a faith or engage a tradition. The following numbers are derived from a variety of sources, and I am uncertain - indeed sometimes dubious - about the criteria probably used to estimate them. Often there are national guesses of Hindus relative to Muslims, with both numbers assumed to reflect the presumed proportions of these religions in the parts of India whence migrants came. None of the available data for any place can suggest to us 'how Hindu' people are, or indeed, 'how they are "Hindu"'. All the numbers below can really indicate are rough aggregates relating to people whose heritage - despite whether or how it is continued - falls within that broad category of traditions that have come to be constructed as 'Hinduism'.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Online suggests there are 761,689,000 Hindus spread across 144 countries. This amounts to 12.8 per cent of the world's total population of around 6 billion. Enumerating by world region, the Encyclopaedia lists 755,500,000 Hindus in Asia, 2,411,000 in Africa, 1,382,000 in Europe, 785,000 in Latin America and 345,000 in Oceania.

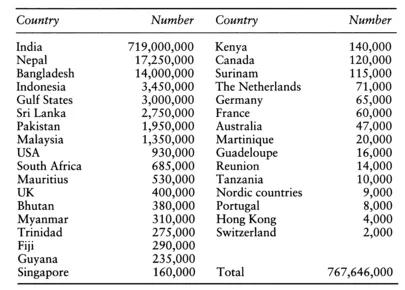

Table 1.1 gives some broad estimates for Hindu populations around the world (based on figures from the CIA World Factbook, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, the Himalayan Academy, Barrett 1982, Thiara 1994, Prins 1994, Bilimoria 1997, Coward 1997, Baumann 1998, Rogers 1998a, Voigt-Graf 1998).

There are certainly some discrepancies between the estimates in Table 1.1 and those offered by Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, but, as broad estimates go, the numbers are not irreconcilable. As Table 1.1 indicates, outside of India there are around 48,646,000 Hindus among a larger Indian diaspora that includes Sikhs, Muslims and Christians (as well as Jains, who are counted as Hindus in some estimates).

Outside of South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan), there are perhaps 12,316,000 Hindus. In Indonesia, where there are said to be 3.4 million Hindus (2.7 million in Bali alone), Hinduism has been an important part of the cultural context

Table 1.1 Estimated Hindu populations, mid-1990s

since the fifth century AD. Therefore, in Indonesia Hinduism can be said to be more 'at home' than 'in diaspora'. The remaining number of Hindus around the world - almost 9 million - are located where they are mainly by way of some experience or history of migration. The massive population of Hindus in the Gulf States such as Oman, Bharain and Saudi Arabia (where numbers can only be guessed at due to extensive illegal migration) is largely made up of contract labourers who spent relatively short periods outside India, often replacing each other in succession. The rest of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Tracing transformations of Hinduism

- 2 'Official' and 'popular' Hinduism: historical and contemporary trends in Surinam, Trinidad and Guyana

- 3 Religion and ethnic ideology: the Hindu youth movement in Trinidad

- 4 Reproduction and representation: the growth of Hinduism in Britain

- 5 Category and quandary: Indo-Caribbean Hindus in Britain

- 6 Community and congregation: Hindu temples in London

- 7 Three meanings of 'diaspora'

- 8 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Hindu Diaspora by Steven Vertovec in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.