![]()

The changing nature of work

Council of Churches for Britain and Ireland

Historians looking back to the closing decades of the twentieth century may well identify our own times as the crucial period of a new industrial revolution. Certainly they will identify some profound changes in the nature of work. It is too soon to make such historical judgements, as these changes are still taking place around us now and their full implications are far from clear. But already we can see that there are pervasive effects on economic organisation and living standards, on family and household structure, and on community and social cohesion.

Our way of thinking about work in our society is so conditioned by the modern world as it developed out of the industrial revolution of the late eighteenth century that it is not easy for us to stand back and view it as if from the outside. Yet this is necessary if we are to address the issues, and make the choices, on which depend the character of our society in the future. Our Christian inheritance can be invaluable, stretching back as it does over two thousand years and not a mere two hundred. It is not dependent on the experience of just one form of economic organisation. It gives us a framework of values, or a decisive point of reference, as we try our best to address some important and complex questions about the future of work and of employment.

The issues addressed in this report are of great concern to all sections of society, and they are being actively studied from many different points of view. (…) We believe that, as an expert working party set up by the churches, we have an important and distinctive contribution to make to the debate.

We have found it helpful to distinguish three different strands in the web of social change, although they are all closely related and mutually interactive. The first is the introduction of new technology, especially in communications and information processing. The second is the changing composition of the labour force, with male participation rates falling and female participation growing. This has profound implications for the workplace as well as the home. The third is the liberalisation or deregulation of markets resulting in greater intensity of competition both within our countries and internationally. Much else is happening in our society at the same time which could be thought relevant to our enquiry, not least the changes in religious belief and the role of our own churches, but it is on these three trends we will concentrate our attention. We will describe them in a preliminary way in this chapter of our report. Their consequences are the challenge that we see to society today. We have no choice but to enter a new age, with new technology, global markets and increasingly equal opportunities for men and women in employment, but we do have a choice about the future of work and of unemployment in that new society.

New technology

We are told that before long the storage and transformation of information in any form will become almost costless, and so will be its communication to anywhere in the world. Once an information system is set up and running there will be almost no need for human beings to be involved in any of these operations anymore. In the past, machines have replaced physical effort and stamina, now they are replacing patience and manual dexterity, knowledge and skill as well. To give just one example we met out of the thousands we might have observed and quoted, computers have now taken over from scientists with PhDs the task of carrying out routine tests on the chemical properties of newly developed medicines. This illustrates the point that it is not only what are conventionally thought of as ‘unskilled’ jobs which can be made redundant by technical change. Currently, we are advised, it is particularly the skilled or semi-skilled jobs in data processing that are most at risk, not least the new jobs created by earlier generations of computer technology.

On our industrial visits we have been impressed, like any group of relative innocents, by the precision of computer-driven manufacturing machinery, for example in a modern shipbuilding yard. A vast and complex structure can be assembled according to a pre-set design and time schedule with relatively little human effort, because the process is guided by the information which is stored and transmitted very cheaply and accurately in a multitude of computer installations. We may see such processes as humbling or threatening, but we should also celebrate them as magnificent achievements of human ingenuity.

Another, not altogether trivial, example is worth recording. One member of our working party, Kumar Jacob, is a manager in a software company which designs and makes computer games. Some of us visited the firm and were duly impressed by the technology on display. Computer games, of this very sophisticated kind, may suggest lessons to be learnt about the use of computers at work as well as at play. They depend for their fascination on the interaction of human and mechanical abilities. The role of the human mind is active, not passive, requiring imagination and strategic vision very different to that possessed by the machine. We must bear this in mind when futurologists tell us that computers will make all human labour obsolete.

An American book, The End of Work by Jeremy Rifkin (1995), begins with a disturbing vision:

From the beginning, civilisation has been structured, in large part, around the concept of work. From the Palaeolithic hunter/gatherer and Neolithic farmer to the medieval craftsman and assembly line worker of the current century, work has been an integral part of daily existence. Now, for the first time, human labour is being systematically eliminated from the production process.

In another passage he considers the long-term implications of artificial intelligence. ‘Nicholas Negroponte of the MIT Media Lab,’ he tells us

envisions a new generation of computers so human in their behaviour and intelligence that they are thought of more as companions and colleagues than mechanical aids.

We need to reflect critically on this ‘envisioning’. It raises some deep questions, including some religious questions, about what it means to be human and about how human work differs from the work we can get out of a machine, however intelligent. When we say that human beings are made ‘in the image of God’ we mean, amongst other things, that they are creative. Much of the work which human beings actually do is not like the work of God at all, because it is repetitive, boring and essentially mechanical. That kind of work could well be mechanised. But the element which we describe as creative is different in kind as well as degree. No machine now in existence is creative in that sense; it is a matter of dispute amongst scientists and philosophers whether a truly creative machine is possible as a matter of principle.

There is, in any case, a great range of tasks which of their very nature only a human being can perform. They involve human relationships. The more obvious examples may come from the caring professions, but a similar point could be made about jobs which involve, persuasion, selling something or public relations, and about jobs which involve aesthetic or moral judgement. It is no accident that careers guidance nowadays puts so much stress on the need for ‘interpersonal skills’. A well-drilled computer programme may be able to mimic some such skills, but only as a form of deception. A vast number of jobs require the real thing.

Even if, as we believe, new technology does not exactly spell the end of work, it does nevertheless imply some fundamental changes in its nature. On the whole these changes should be beneficial, as were most of the long-term effects of earlier industrial revolutions. If machines can take over what is mechanical in human work, what is left should be better suited for humans to do. E. F. Schumacher (1980) in Good Work described most forms of work, whether manual or white-collared, as ‘utterly uninteresting and meaningless’. ‘Mechanical, artificial, divorced from nature, utilizing only the smallest part of man's potential capabilities’ he described work in an industrial society as 'sentencing the great majority of workers to spending their working lives in a way which contains no worthy challenge, no stimulus to self-perfection, no chance of development, no element of Beauty, Truth, or Goodness'. His son, Christian Schumacher, has developed the concept of ‘Whole Work’, based on analogies between the structure of human work and Christian theology. He says that every job should involve planning, doing and evaluating; every job should perform some complete transformation, whether of material or of information, for which the workers can take responsibility; workers should be organised into teams whose members are responsible for one another. These ideas also relate well to new styles of management made possible by new technology. People work better when they are treated more as human beings, less as machines. It becomes increasingly possible to do this, as information processing takes over the mechanical parts of human work.

Simone Weil (1952), who described the actual experience of work in very negative terms, wrote in The Need for Roots (written in 1943) that liberation would come from new technology. ‘A considerable development of the adjustable automatic machine, serving a variety of purposes,’ she wrote, ‘would go far to satisfy these needs’ – that is the need for variety and creativity as well as relative safety and comfort. ‘What is essential is the idea itself of posing in technical terms problems concerning the effect of machines upon the moral well-being of the workmen.’ Haifa century later the need to pose such problems is even more evident, and the potential to solve them greatly enhanced. Technical advance can and should be a liberating and humanising influence on the future of work. Whether it is in fact so depends on the economic system and the choices people make within it.

A textbook on the subject, The Economic Analysis of Technological Change by Paul Stoneman (1983), concludes as follows:

The nature of the development of the economy that is likely to result from this complicated and involved process of technological change is not necessarily going to be ideal. Reductions in price and increases in consumer welfare may result, but these may only be generated at a cost … Nobody pretends that, in a world where decisions are made on the basis of private costs and benefits, the world will normally behave in a socially optimal way.

When a new product or process is introduced there will always, in a market system, be winners and losers. Some of the winners will be easy to identify because they will be the owners of the innovating firms and those workers who have a stake in them. The other winners will be more difficult to point out because they will be members of the general public who enjoy a better product at a lower price. The losers will of course be the owners of the firms that compete with the innovation and especially the workers who lose their jobs. Typically they will move to much lower paid employment, if indeed they do not remain unemployed. (…)

Even at this stage, however, we can make one thing clear. We have not seen or heard anything which convinces us that work has no future. Certainly there are needs to be met and many of those needs can be met only by human effort. It is not only the very clever, well educated or uniquely qualified people whose work is needed. Even a four-year-old child can do some things much more efficiently than the best computers in the world. The problem is one of social organisation. How can we match the potential of the people who want to work with the needs that exist, given the stock of equipment and the resources, and given the state of technical know-how? There is no reason why we should assume that this problem has no feasible solution.

The supply of labour

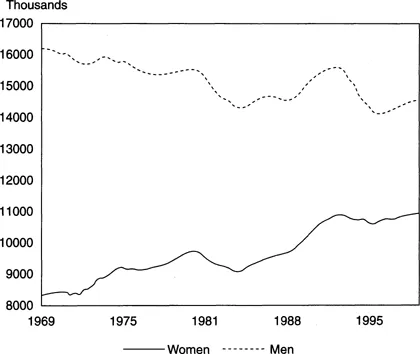

As our society gets richer one might suppose that people would choose to work less hard. With a larger stock of capital invested in machinery and infrastructure, with increased knowledge and technical efficiency, the same standard of living could be achieved with less human effort. It would be reasonable to expect – indeed it would be a prediction of standard economic theory – that most people would choose to take some of the benefit of higher productivity as increased leisure, or perhaps in undertaking some kind of unpaid work which they enjoyed doing, rather than taking the whole of the benefit as higher income and more consumption of goods and services. Yet looking back over the past generation there has been little change overall to the supply of labour to the market economy. One indicator of this is the proportion of the population aged 15 to 64 who are recorded as being in the labour force, that is to say either in work or actively seeking work. For the advanced industrial countries in aggregate (the OECD area) that proportion was 69.6 per cent in 1960 and 70.8 per cent in 1990. The fall in the male participation rate was almost exactly offset by the increase in the female participation rate. Similarly in Britain between 1985 and 1996 the activity rate overall was unchanged at 62.8 per cent: the rate for men fell from 76.4 to 72.3 per cent whilst the rate for women rose from 50.3 to 53.8 per cent. Figure 1.1 shows the numbers of men and women employed in Britain since the late 1960s.

The fact that women as well as men now expect to take part in paid work is itself a change in the nature of work and for society of immense significance. It is at least as important and as challenging as the development of new technology. We need again to take a long historical perspective and note how the industrial revolution brought about a very sharp distinction

Figure 1.1 Employment of males and females (including self employment)

between the work that men and women do. In a pre-industrial society men and women were more often working together and organising their work in similar ways. In a post-industrial society, if that is the right term to describe the pattern of life and work now emerging, men and women may again see their tasks as, in many if not all respects, the same.

The sociologist Anthony Giddens (1994) has described how heavy industry required a division of labour in which men's physical strength and endurance was stretched to the limit. This was possible only if women were able to give them both practical and emotional support:

Women became ‘specialists in love’ as men lost touch with the emotional origins of a society in which work was the icon. Seemingly of little importance, because relegated to the private sphere, women's ‘labour of love’ became as important to productivism as the autonomy of work itself.

(Beyond Left and Right, 1994: 196–7)

In pre-industrial society the family was often the unit of production. Husband and wives, parents and children, worked together at common tasks, typically farming a small plot of land, doing some small-scale manufacturing, or running a small shop. Following the industrial revolution all this changed. By the early twentieth century, work had come to mean quite different things to different members of the family. The husband was the breadwinner, working full time, if he could, from when he left school to when he retired. Typically he worked as part of a large team in a hierarchical organisation with its own sense of community and strong bonds of mutual loyalty. His responsibility was limited to just one function within a larger whole that he did not need to understand. Work was like being in the army. It required discipline, loyalty, stamina and courage. It was a duty you owed to your wife and children. It was your fate, not something to be chosen or changed.

All this is now passing into history. Many of the traditionally male jobs, in mining and manufacturing for example, have disappeared. At the same time traditionally female jobs, in services for example, have increased. These changes in the composition of output are one part of the revolution which is going on, but not the whole of it. Thanks to changing attitudes and legislation women have access to jobs previously closed to them. At the same time some women are obliged to take low-paid jobs to supplement the family income. It is a complex picture. The changing composition of the labour force has effects which interact with the changes that are due to new technology and new approaches to personnel management. The structure of work in most industries is becoming less hierarchical, with more scope for initiative at all levels. Work is still as a rule separated physically from the home, but they are no longer two different worlds. Employers sometimes try to be more ‘family-friendly’. Work and family are both having to make compromises. We are in a period of transition, a period of particular stress, as the old patterns conflict with the new. Women are often trying to fulfil the roles of housewife and worker simultaneously, which is a very demanding combination indeed. There will be pressure for further changes both at work and at home.

During our visits we have heard concern expressed that there are now no longer enough jobs for men. Employment is declining in manufacturing, transport, mining and other industries which have in the past been largely male territory,...